Most photographs of Aby Warburg, who was born in Hamburg in 1866, the eldest son of a Jewish banking dynasty, show a melancholy man, gaze withdrawn or staring into the distance. In others, we glimpse a different character – intense, lively, exuding a manic energy. His four brothers went into the family firm, but Warburg was more interested in other sorts of currency, trading in his birthright for a limitless supply of books. He regarded himself as an independent scholar rather than a professorial historian, working outside any institution. Today he is less known for his writing (his subject was the early Renaissance) than for the creation of an extraordinary library, now housed in the Warburg Institute in London, and the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, both models of his mind in its febrile cross-pollination.

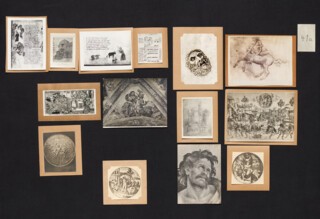

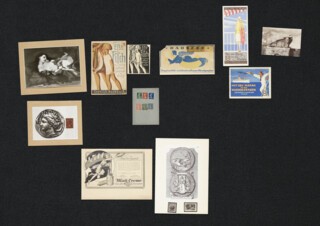

The Bilderatlas (‘picture atlas’) was a continually evolving display of almost a thousand images, mostly black and white, ranging from Babylon to Weimar Germany – with long stopovers in ancient Greece and the Renaissance – spread out over 63 numbered panels covered in black hessian. Warburg juxtaposed reproductions of artworks with astronomical and astrological charts, diagrams, advertising brochures, newspaper clippings, postage stamps and photographs, in an attempt to create something like a flowchart of Western civilisation, mapping the migratory routes of images with their undertow of human drama and emotion.

The curators of Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (until 30 November), have reconstructed the atlas from its last, and quite advanced, version of 1929.* The lighting is dim and the panels are suspended on thin metal wires, casting rhomboid shadows on the floor – a control and geometry far from the London institute, with its exuberant shelves (the books are catalogued by theme: Image, Word, Orientation, Action), footed filing cabinets and centrifugal spirit. In order to recreate the Bilderatlas, the curators, Axel Heil and Roberto Ohrt, sifted through 400,000 images, cross-referencing the vast Warburg archive against images and accounts of the 1929 atlas. After three months they had managed to locate around 80 per cent of the original photographs (the remaining images have been reproduced). They have found ways of remaining faithful to his affinities. The arrangement of panels is elliptical – the reading room of Warburg’s library was modelled after Kepler’s ellipse – and sinuous: Warburg became interested in the serpent motif early on, tracing its undulations through the waves of mythological seascapes, drapery, veils and coiled hair.

In the four years before his death in 1929, Warburg shuffled these images back and forth across the boards, using them for lectures and for research – a sort of workshop or laboratory in which he was able to illustrate different progressions of thought. His eccentric methods were well documented by his assistant, Fritz Saxl, who described the way Warburg’s research was animated by the handling of images and their visual display; he constantly rearranged his books, too, creating possible paths of conjecture. Each new idea would call for the collecting and ordering of relevant volumes. He kept his personal notes in card boxes, Zettelkästen, and constantly reshuffled these as well, spreading them out across a table. Exceptional importance was attached to the placement of objects on his desk, as if it were a map of the cosmos.

At the HKW show, Warburg’s archive is unpacked, his library distilled, his tools laid before us. There is madness in the method but also evidence of a brilliant, obsessive mind. He departed from the 19th-century approach to art history in favour of a non-linear, interdisciplinary reading that drew heavily on psychology and ethnography.

Booklets providing captions are available at the entrance to the exhibition but apart from these, and a few introductory texts, there is little explication. The effect is dreamlike. From a distance some panels resemble a deconstructed frieze, or funerary stele. As you draw closer, you become aware of the many strange marriages and collisions. Warburg believed that modernity was haunted by an irrational, pagan antiquity, a kind of mythopoeic thought that held everything together. The opening three panels, A-C, are the nerve centre of the Bilderatlas, from which all the following panels unfurl. Panel A shows a map of astrological figures, a diagram of cultural exchange routes in Europe, and a genealogical tree of the Tornabuoni, a Renaissance banking family – ‘different systems of relationships, cosmic, earthly, genealogical, in which humanity is involved’. Panel B features images from the zodiac, Hildegard von Bingen’s Scivias, Leonardo’s Vitruvian man and magical compendia – ‘different degrees in the application of the cosmic system to mankind’. Panel C displays Kepler’s planetary orbits and a medieval vision of Mars juxtaposed with newspaper clippings of the Graf Zeppelin that crossed the Atlantic in 1928: early fantasies of outer space border a new technological age in the conquest of the sky.

Nearly all the panels feature human figures, or gods that resemble humans, or human-animal hybrids. The mood swings between ecstasy and melancholy, undercut by currents of violence. Panel 41a features more than a dozen representations of Laocoön, the Trojan priest who was strangled to death, along with his sons, by two immense sea serpents – a punishment from Athena for warning the Trojans about the wooden horse. The Laocoön sculpture excavated in Rome in 1509 isn’t depicted: Warburg wanted to show that ‘if the Laocoön hadn’t been excavated, [the people of the Renaissance] would have had to invent it.’ One engraving shows Laocoön standing with arms raised as he fights off the snakes; in others he’s seated, contorted in pain. His expression ranges from fury to despair to restraint or resignation. Warburg was greatly influenced by Gotthold Lessing’s essay on Laocoön, the central text of the German Enlightenment, and particularly by the idea that an emotion such as agony could be represented in a range of modes. He gave the name Pathosformeln to the recurring gestures, or symptoms, that carve a path of social memory across different forms of representation: a certain pose, say, migrating from a tomb carving to a postage stamp. Images were, he thought, uniquely expressive of emotional undercurrents often lost to textual history.

The smaller displays behind the snaking panels offer glimpses into the physical world surrounding the Bilderatlas: photographs of the atmospheric Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek in Hamburg where, despite Warburg’s mistrust of technology (‘having enslaved electricity, captured lightning in the copper wire, man has created a culture that leaves no room for poetry’), the building was fitted in his absence with twenty phones, a conveyor belt for books and a pneumatic post system. In 1921 it was converted into a research institute. A display of the versos of particular images (the life less glimpsed), many with Warburg’s own handwritten annotations, key words and inscriptions, allows us to trace the journey of an image through the archive, identifying the places it previously occupied, the ideas it illustrated. Along the facing wall hangs a copy of an earlier version of the atlas: twice removed from the source, it has an even more spectral presence than the ‘final’ iteration.

A parallel and much smaller exhibition at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (until 1 November) has assembled fifty of the original works reproduced in the Bilderatlas, all from Berlin museums, allowing us to visualise certain aspects of Warburg’s method and scholarship. The hierarchy of artworks is reinstated, emphasising the way he distorted images to suit his purposes, scaling up and scaling down, zooming in and out, cropping, editing, manipulating. At the Gemäldegalerie, a coin no longer has the same dimensions as a sculpture; here, you can discern the horses in Rembrandt’s Abduction of Proserpina.

Warburg was obsessed with the figure of the nymph and created a weird sisterhood of menacing and alluring maidens, all portrayed with dynamic folds in their garments. The Gemäldegalerie curators have displayed a bronze statue of a three-faced Hecate without the pedestal under her raised foot in order to highlight her instability – a precarious stance echoed by Ghirlandaio’s Judith and Filippino Lippi’s Erato nearby. One early 18th-century Norwegian bridal box, with primitively drawn interlocking figures, had lain in storage for many years, displayed only once, in the 1990s. At the HKW I’d hardly noticed it, eclipsed by other images on Panel 32: jaunty Morris dancers and Dürer’s engraving of dancing monkeys. The real box depicts a curious scene, the Battle of the Trousers, in which seven women fight over a pair of trousers. Warburg related the image back to a passage in Isaiah, in which the shortage of men in Zion causes a fight to break out among a group of women. He bought the box on one of his collecting trips and later donated it to the Museum Europäischer Kulturen. Something mysterious rattles about inside; once the show is over, the curators are planning to pry open the lid.

Warburg described Burckhardt and Nietzsche, two of the figures who most influenced his thought, as ‘highly sensitive seismographs’ whose inner convulsions mirrored those of their times. As he attempted to reveal the unconscious life of images, his own nervous symptoms became more pronounced. In 1918, exhausted by war and what he saw as the collapse of civilisation, he suffered a breakdown and spent almost six years in institutions, most significantly at the Bellevue sanatorium in Kreuzlingen, a clinic run by the Swiss psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger, the founder of ‘existential analysis’ (‘the Dasein is not the individual; it is the background upon which the individual emerges’).

Far from his library, Warburg worked in notebooks, filling them with often indecipherable pencil scrawls – threads unravelling and cascading down the page. Psychotic episodes alternated with lucid spells. The philosopher Ernst Cassirer visited him and they discussed the library, of which Cassirer had become a willing ‘prisoner’, as well as Kepler and the ellipse. Other interlocutors included the moths that flew into Warburg’s room at night. In letters he described them as his Seelentierchen, his little soul animals. Georges Didi-Huberman writes of the way in which the insects, with their erratic, exploratory flight paths, anticipated the Bilderatlas in its exploration of the dynamic tension of images set against a nocturnal backdrop. And it was at Kreuzlingen that Warburg delivered his Serpent Ritual lecture, inspired by a visit to the Hopi Indians in New Mexico and Arizona nearly thirty years earlier. Although absent from the Bilderatlas, it was an experience that reinforced his belief that the magical thinking of ‘primitive’ man was still present, sublimated into art and ritual. Here the snakes from Laocoön came alive, writhing in the hands of dancers and echoed in representations of lightning bolts.

As he recovered, Warburg began to confront the grief and calamity of the culture he’d devoted his life to studying. His reading became increasingly steeped in anthropology and psychology; his focus centred on humanity’s primal, irrational urges. The Bilderatlas is the landscape of these final years. He referred to the project as an ‘iconology of the interval’ and it is the empty spaces in the panels, filled with unknown and uncertain matter, that hold the images in constellations of thought. In the final three panels, the present day begins to intrude. An advertisement for body lotion in Panel 77 shows an airborne girl carrying a laurel wreath besides the words Sieg der Jugend (‘Victory of Youth’). Somewhere around her floats Delacroix’s Medea and scenes from The Massacre at Chios, as well as timetables for a North Sea ferry and postage stamps of Queen Victoria in the shell carriage and King George V as Neptune. Panel 78 charts the rise of Mussolini; Warburg was in Rome in 1929, and witnessed what he called its ‘repaganisation’. The final panel includes a photograph of a hara-kiri ceremony, two late 15th-century depictions of the desecration of the host by Jews, photographs of Catholic masses celebrating Mussolini, and front pages of newspapers with images of golfers and, again, Il Duce. The Bilderatlas was inspired by Mnemosyne, but also pre-empted the violence of the Holocaust and other tragedies of the 20th century.

Warburg died of a heart attack in October 1929, aged 63. In an increasingly hostile climate – the Bauhaus evacuated, bonfires of books in Berlin, letters delivered to the Warburg Library calling it a ‘nest of Jews’ – his family and librarians had to decide quickly on the fate of the collection. An English connection, and the insistence of Saxl, meant that London was chosen. In December 1933, sixty thousand books and fifteen hundred photographs were shipped over on the Hermia. The library furnishings followed in January.

At the far end of the HKW exhibition hangs a row of portraits of the directors of the Warburg Institute, of which the most fiercely loyal was Gertrud Bing, who had accompanied Warburg on his trips to Italy and who, along with Saxl, took many of the major posthumous decisions concerning the archive. She carried on Warburg’s taxonomical work, grouping the images into categories and subcategories. The Warburg Institute has seen off closure on more than one occasion and continues to provide a wonderful and idiosyncratic scholarly resource. Yet Warburg’s own reputation was contested among his heirs. When Ernst Gombrich called him a ‘man lost in a maze’, Edgar Wind rose to his defence. ‘No doubt there was some obsessional quirk in Warburg’s over-extravagant habit of preserving all of his superseded drafts and notes, thus swelling his personal files to gargantuan proportions, with comic side effects that did not escape him.’

Warburg intended the Bilderatlas to be published in three volumes – one volume of images and two of historical and critical commentary – and modelled it after the illustrated atlases of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, to which it is frequently compared, it could never really be completed. But its fragmentary and elliptical character doesn’t diminish it – quite the opposite. It’s all the more fascinating for being inherently melancholic, incantatory and unresolved (Matthew Vollgraff of the Warburg Institute calls it a modernist ruin); by reconstructing the atlas, the curators have revived it as a site of contemplation. Of the abundant supplementary text Warburg had intended, only a few cryptic notes exist, leaving it open to endless interpretation. Warburg himself remains an elusive figure, onto whom it is easy to project one’s own theories and obsessions. His final vision, the Bilderatlas, can be approached as an archaeological artefact or as an instrument of inquiry.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.