There is something perverse about the imagery of the Belgian artist Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946). His neatly made ink drawings and watercolours of objects, rooms and seascapes, until recently on display at the Royal Academy (the exhibition can be viewed online) convey a psychological feeling for the inert, but little or no emotional connection to the things they depict. Women stand alone by the shore, waiting; men sit in rooms, staring into a mirror or empty space. These ghostly works seem to have more in common with Chinese ink painting than with the art of fin-de-siècle Belgium. There is life in the ordinary objects Spilliaert paints – a blue bowl, perfume bottles – but it is an animal life, strange and unknowable.

The austere Belgian coast – not known for its beauty – and his native Ostend were Spilliaert’s inspirations, just as for his contemporary James Ensor. Yet where Ensor transformed his source materials into a bizarre, brightly-coloured pageant, Spilliaert saw the North Sea coast as a place of stillness and isolation. The town meets the shore uneasily at Ostend – vast sand flats stretch out beyond the grandeur of the Kursaal and the Galeries royales, both built in the time of Leopold II. These structures, particularly the pillared arcade of the Galeries royales, are the most animate elements in Spilliaert’s images. The arcade was completed in 1906, and must have seemed an alien intrusion into the town where he was born and where his parents ran a hairdressing salon and perfume shop (hence those bottles). Spilliaert had the briefest of art educations in Bruges – a matter of months at the Academy of Fine Arts, before he became ill with the stomach ulcers that kept him awake at night – and spent the rest of his life moving between the city and Ostend, with occasional trips to Paris.

It was the coast that mattered to him. It appealed to other artists, too. In 1909 Piet Mondrian began painting at Domburg, just north of Ostend, producing stark visions of sea and sky – his first steps towards abstraction. Twenty years earlier, in the French port of Gravelines, south of Ostend, Seurat had painted the salt air in brilliant points of colour. Spilliaert saw the coast differently, perhaps because of his obsession with monochrome ink and watercolour drawing, perhaps because of his insomnia, which meant he saw it at night and in the pale early morning. His compositions – washes, lines and areas of darkness or shadow – are laid out with precision. Their appeal comes from his peculiar directness of vision, both sharp and unspecific, which suited his subjects: the long horizon line of the sea at Ostend, the endless columns of the Grand Hotel, seen through a murky northern light.

Like Edvard Munch, and almost every other artist of the day, Spilliaert admired Nietzsche, and made several portrait drawings of him from photographs. He was not himself a Nietzschean personality – too reticent, too self-absorbed, unconcerned with the Classical past or with overcoming the present. And although Spilliaert saw Munch’s work in Paris in 1904, Munch’s attempts to find pictorial metaphors for human relationships and emotions, particularly sexual ones, seem not to have interested Spilliaert at all. Superficially, there are similarities – they both knew how to make a bold graphic image (Munch particularly in his prints) and both dwelled endlessly on favoured motifs – but Spilliaert’s motifs are the stranger; more literary and more fantastical.

He read the writers of the day in the lending libraries of Brussels, including the one owned by the publisher Edmond Deman, known for producing luxury books illustrated by leading artists, including Manet and Renoir as well as the Belgian artists Fernand Khnopff and Théo van Rysselberghe. Khnopff’s illustrations for Georges Rodenbach’s Bruges-la-Morte (1892) were typical of these collaborations and the mood of Belgian art in the 1890s: a combination of German and English Romanticism, medieval poetry and Arthurian legend. Spilliaert for his part illustrated two collections of poetry by Émile Verhaeren (who became a friend and supporter) and hand-illustrated, in a unique edition, a three-volume compilation of Maurice Maeterlinck’s plays (included in the exhibition) filled with dreamlike visions of loneliness.

Rodenbach’s novel helps us look at Spilliaert too. The hero, Hugues, likes the ‘dead town’ of Bruges because it mirrors his melancholy after the death of his wife. ‘Every town is a state of mind,’ Rodenbach writes, ‘a mood which, after only a short stay, communicates to us.’ His description of Bruges evokes Spilliaert’s Ostend:

Everywhere along the streets the façades shade into infinity. Some are of a pale green wash, or faded brickwork, repointed in white. But beside them are others of black, austere charcoal drawings, burnt etchings whose inks moderate, compensate for the somewhat lighter neighbouring tones. But what emanates from the whole is still grey, drifting, spreading along the alignment of the walls, along the quais.

It was in the years after 1900, in Brussels and then Ostend, that Spilliaert began to develop his distinctive style of ink drawing, for instance in stormy romantic scenes such as The Old Lighthouse at Dusk from 1901, which shows the wind whipping skeins of sand over the vast beach at Ostend. The colours brighten slightly in his interiors, though the quality of detachment is just as strong. One important precursor was the Belgian artist Xavier Mellery, who studied at the Brussels Academy in the 1860s. His monochrome conté crayon drawings of mysterious interiors, exhibited at the Société Royale Belge des Aquarellistes in 1889 under the title The Life of Things, bring to mind Seurat’s atmospheric tonal drawings. Unlike Seurat, however, Mellery’s intimiste scenes are laced with melancholy and menace. They anticipate the pictures Spilliaert made of interiors in his family home, empty rooms filled with silent, charged objects, abandoned to the night: in The Bedroom (1908), a white-sheeted bed, luminous in moonlight, faces a window; you feel, looking at it, that it yearns to float out.

Spilliaert’s best years were undoubtedly those around 1907, when his images of the shore attained an extreme simplicity of composition and show him looking forward to modernism: his images of the breakwaters on the beach at Ostend foreshadow Paul Nash’s images of the beach at Dymchurch in Kent 15 years later. Aside from his self-portraits, the most affecting images at the exhibition are these darkened seascapes, such as Signal Pole on the Pier of 1907 and Breakwater with Pole of 1909. Displayed behind glass, the dark images become mirrors, putting the viewer into the empty seascape.

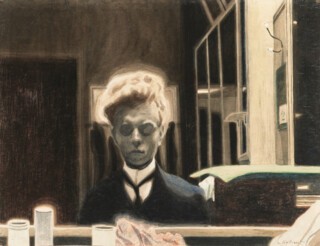

Spilliaert also responded to photography, evidenced by the striking self-portraits he made between 1907 and 1908. In one, from November 1908, he looks sideways at a mirror, his face drawn, a great pile of illuminated blond hair resting on a dramatic high forehead. His extraordinary appearance was noted at the time: a local journalist describing it as ‘quasi-fantastique, Hoffmannesque’. When he registered briefly as a student at the Academy of Fine Arts, he listed his second job (a requirement of all art students) as ‘hairdresser’, a skill he had learned from his father. The self-portraits have the feel of film stills: Spilliaert’s sharp profile, theatrically lit against soft-focus interiors. Vertigo, an ink drawing from 1908, shows a woman descending steep curved steps, a scarf billowing behind her. It takes us from Ostend to Salvador Dalí’s dream sequence for Hitchcock’s Spellbound, and then just as quickly back again to Ostend.

Joris-Karl Huysmans wrote that it was difficult for artists to gain recognition in the late 19th century unless they used oil paint (he was talking about Jean-Louis Forain). This might explain the neglect of Spilliaert’s work during his lifetime, but not since. Following his death in 1946 he had numerous exhibitions in Belgium, and wasn’t unknown abroad. Now his peculiarly cold vision strikes a chord. La Digue, a painting of a solitary beach hut by a seawall (not at the RA), foreshadows the bare paintings of the Scottish painter Craigie Aitchison. Tree behind a Wall, from 1936, could be a George Shaw. But Spilliaert is best seen in his own time, in the moody coastal gloom of Ostend, and the shadowy rooms of his childhood.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.