Almost from the moment she published The Second Sex in November 1949, Simone de Beauvoir was asked why she’d never written a female character who lived a free life, the sort she imagined in her final chapter, ‘The Independent Woman’. If the mother of 20th-century feminism couldn’t imagine a free woman, who could? At first she would answer brusquely. ‘I’ve shown women as they are,’ she told the Paris Review, ‘as divided human beings, and not as they ought to be.’ (She’d said as much in an epigraph borrowed from Sartre: ‘À moitié victimes, à moitié complices, comme tout le monde.’) But in a later interview she answered the same question angrily:

The history of my life itself is a kind of problematic, and I don’t have to give solutions to people and people don’t have a right to wait for solutions from me. It is in this measure, occasionally, that what you call my celebrity – in short, people’s attention – has bothered me. There is a certain demandingness that I find a little stupid, because it imprisons me, completely fixing me in a kind of feminist concrete block.

I know what that feminist concrete block looks like – it has a turban, it wears a black polo neck, it works at the Café de Flore, it has contingent lovers around one essential love, it drinks, it dances, it travels, it talks, it marches, it writes – and I have loved that concrete block as long as I’ve known it existed. It was partly the glamour of that myth that led me to read Beauvoir in the first place, working through both volumes of Le Deuxième Sexe at 21, leaving hopeful questions about the future in the margins: would it always be true that ‘men don’t like tomboys, or bluestockings, or clever women; too much daring, education, intelligence or character scares them’? Like so many other women, I wanted a feminist heroine, and Beauvoir seemed to fit: she had written a work of lasting value and she’d lived a life disdainful of convention – what more could one ask for? Surely that was why she’d written four volumes of memoir – to show us all, in an act of unprecedented generosity, how she’d freed herself. When she was buried in the Cimetière Montparnasse, the waiters lined up outside La Coupole to see her coffin pass. A man carrying his toddler on his shoulders in the funeral throng told Beauvoir’s first biographer, Deirdre Bair, that he wanted to be able to tell his daughter when she was older that they’d paid homage to a great woman. (Engraved over the columns of the Panthéon, a short walk from La Coupole, is the line ‘Aux Grands Hommes, la Patrie reconnaissante’.)

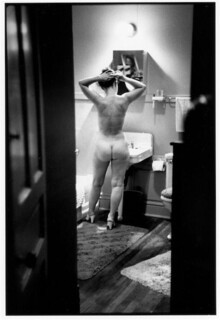

But since April 1986, when Beauvoir died, the idea of her as a feminist heroine has faded. Her letters to Sartre, published four years later, showed her seducing her pupils and then passing them on to Sartre, in a bad modernist version of Les Liaisons dangereuses. She carried on a ten-year affair with the husband of one of her female lovers without the woman knowing. The publication of her letters to Nelson Algren in 1997 made the relationship she had with Sartre look passionless, as did the photo that emerged in 2008 of Beauvoir at 42, pinning her hair up in Algren’s bathroom wearing just a pair of heels. And her insistence that Sartre was the philosopher, not her – because she hadn’t invented a new system as he had done – looks too modest: he often took ideas from her novels, it now seems, not the other way round. The newest volume in the Illinois series of her uncollected writings shows Beauvoir at the beginning of her mythic pact with Sartre wavering between three men; the new memoir by Bair describes a cold, drunk, grumpy old woman; Kate Kirkpatrick’s biography uses the posthumous sources to show where Beauvoir was inconsistent, obfuscatory or even mendacious in her own accounts of herself.

I wanted my heroine back. I hadn’t read Beauvoir’s four-volume autobiography – Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, The Prime of Life, Force of Circumstance and All Said and Done – so I ordered second-hand copies online (only the first is still in print), hoping, among other things, to have her restored to me. I found that she hadn’t claimed any superhuman status for herself: ‘I wanted to make myself exist for others by conveying, as directly as I could, the taste of my own life,’ she wrote at the very end of Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter. Genet said that knowing more about her life had given her ‘more density’; Sartre said that her autobiographical books, particularly A Very Easy Death, about the last six weeks of her mother’s life, were the best things she’d written. She ‘communicates emotionally at once’, he wrote. ‘People are always involved with her by virtue of what she says.’ She herself said that she wrote about her life to ask: ‘I’ve fought to be free. What have I done with my freedom?’ She wasn’t seeking exoneration or canonisation, but to live – with all the messiness that implied – on the page. What if she didn’t experience her own life as that of the concrete block feminist heroine I wanted her to be? And if I really hadn’t grown out of wanting to learn a lesson from her life, might the real lesson be the harder one – to value her life for the mistakes she made as much as for what she achieved, and to accept that they might even be intertwined?

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter came out in France in 1958, when Beauvoir was fifty. It began at the beginning, with her birth in the early hours of 9 January 1908, above the Café de la Rotonde in Montparnasse. There were red silk hangings over the stained-glass doors in the apartment where she grew up, chandeliers, and a mother who, Proustianly, kissed her goodnight in perfumed black velvet before going to dinner; in the summer, the family visited her paternal grandfather’s estate, Meyrignac, near Tulle, where there were magnolia trees, a stream with waterlilies and goldfish, peacocks and wisteria. She was the favourite, even though her parents had wished for a boy – a wish that was even more evident when her sister Hélène, or Poupette, was born. Two days a week she went to a private Catholic school, Le Cours Désir (her mother’s influence), and she liked reading more than anything else (her father’s). ‘I was a madly gay little girl,’ she writes, though what I noticed most in her description of her childhood wasn’t her happiness but her confidence. She had appalling handwriting (Sartre used to complain about it) and always ‘made a mess of hems’, but ‘as soon as I was able to think for myself, I found myself possessed of infinite power … when I was asleep, the earth disappeared; it had need of me in order to be seen, discovered and understood.’ Her confidence, which never left her (‘I have almost always felt happy and well-adjusted,’ she said at 64, ‘and I have trusted in my star’), is astonishing. I have never known a woman, in person or in print, who talks about herself the way Simone de Beauvoir does. That preternatural conviction makes sense of the teenage Simone rejecting God and the social code of the bourgeoisie she was born into; the woman in her twenties believing that she was her lover’s essential love despite evidence to the contrary; the thirtysomething deciding to write a book about the female condition; the fifty-year-old producing a 2000-page autobiography. One day, while drying the dishes her mother was washing, she caught sight of the wives in the windows opposite doing the same thing, and had a vision of domestic life as a horrifying mise-en-abyme. ‘There had been people who had done things,’ she said to herself. ‘I, too, would do things.’ Jo in Little Women helped her work out what things to do, as did Maggie in The Mill on the Floss (she didn’t discover Sand or Colette until later). And so did a new girl at school, Elisabeth Mabille, whom she called Zaza.

Zaza arrived at Le Cours Désir when Simone was ten: she’d been educated at home until burns caused by an accident when roasting potatoes led to a year’s convalescence, and her falling behind with her studies. The tragedy appealed to Simone: ‘She at once seemed to me a very finished person.’ Zaza was skinny and dark, better than Beauvoir at schoolwork, could make caramel and do cartwheels, and used to stick her tongue out during school piano recitals. With Zaza, Simone had ‘real conversations’ for the first time, the kind she thought her mother and father had with each other. They became ‘the two inseparables’. (Elena Ferrante mentions the protagonist of The Days of Abandonment reading Beauvoir’s late novella The Woman Destroyed; but, to me, Zaza and Simone could be foresisters of Lila and Lenù of the Neapolitan quartet.) After a day at Meyrignac eating apples and reading Balzac, both supposedly sinful activities, Simone finally realised she had lost the faith she once thought would send her to a convent – how could she believe in God and sin against him without feeling any guilt? She replaced love of God with another sort, for her cousin Jacques, whom she thought of as something like le grand Meaulnes. Jacques, older, better read and willing to take her to bars, would disappear for weeks on end, and Simone, now studying philosophy at the Sorbonne (the École Normale was still barred to women), would work at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, and take herself to the Louvre, to Chaplin movies, to see Madame Pitoëff in Saint Joan. ‘I would wander all over Paris, my eyes no longer brimming with tears, but looking at everything.’ She began writing novels, abandoning one, ‘Éliane’, after nine pages, and sneaking out for a gin fizz at the Jockey with Poupette: after one drink her ‘loneliness evaporated’. She came across Simone Weil (they didn’t get on); she made friends, most of them male students at the Normale. Zaza fell in love with one of them, the once and future Maurice Merleau-Ponty, despite her parents’ opposition, and although Simone thought later that she had fallen in love with the ‘image’ of Jacques rather than the man himself, she still wished he were in Paris and not in Algeria doing military service. One group of normaliens, known for its ‘brutality’ (they threw water bombs on students ‘returning home at night in evening dress’), was the ‘little band’ of Paul Nizan, René Maheu and Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre was rumoured to be ‘the worst of the lot’.

Beauvoir was preparing for her exams, full of love for Zaza, constantly addressing herself in her diary to the absent Jacques and giddy for the married Maheu. She began to talk philosophy with the ‘petite bande’ in the bars and gardens of the Latin Quarter, while ostensibly revising for the agrégation which would guarantee her a teaching post somewhere in France. She called Maheu her Lama (he gave Beauvoir her lifelong nickname, Castor, French for ‘beaver’, because she was ‘always fussing and working’), and admired everything about him, from the way he popped his collar to the way he teased her. ‘You’re interested in everything,’ she records him saying in her diary for summer 1929. ‘That’s why I reproach you.’ (Maheu seems to have been the first person she slept with, though she protested to Bair that she was still a well brought up Catholic girl at this point.)

Sartre’s early attempts to capture Beauvoir’s attention fell flat. ‘Sartre gave me as a gift some absurd pieces of porcelain won for me last night and a vile twopenny novel for my sister,’ she wrote in her diary. Seven days later, over cocktails at the Falstaff, she was beginning to reassess the situation: ‘Lama makes a woman feel attached to him just by softly caressing her neck, Sartre by showing her heart to her – which one more surely enslaves her?’ Five days after that, she wrote of Sartre: ‘Intellectual need for his presence, and emotional turmoil in facing his affection. Doubts, upset, exaltation. I would like him to force me to be a real somebody, and I am afraid.’ Sartre brought her the results of the agrégation (he came first, she second), and announced that from ‘now on’ – it was June 1929 – ‘I’m going to take you under my wing.’ Beauvoir was 21. He urged her to try to ‘preserve what was best in me: my love of personal freedom, my passion for life, my curiosity, my determination to be a writer’; she thought she had found the ‘dream companion I had longed for since I was 15’. Jacques had returned from Algeria and got engaged, as he told Simone sheepishly, after a three-week courtship. His marriage, she later noted, turned out to be one of ‘moderate rapture’; their families stopped talking, but for years afterwards she would catch sight of him in the bars of Montparnasse, ‘lonely, puffy-faced, with watering eyes, obviously the worse for drink’.

Zaza was preparing with ‘frenzied’ optimism to go to Berlin (her parents had thought separation the best way to discourage the match with Merleau-Ponty), where she foresaw a year of love letters and reading Stendhal. But the day after Simone and Zaza had said goodbye, Zaza fell ill. Delirious, with a temperature of 104°, she turned up at Merleau-Ponty’s door and demanded his mother explain why she didn’t want them to marry. When Merleau-Ponty himself arrived she turned on him too: ‘Why have you never kissed me?’ He kissed her. Under pressure, both sets of parents backed down: the marriage could go ahead, but first Zaza had to get well. She was transferred to a clinic in Saint-Cloud – ‘my violin, Ponty, Simone, champagne’, she would cry out again and again. Four days later, she died. The next time Simone saw Zaza she was laid out on a funeral bier, surrounded by flowers and candles, her face thin and yellow. The doctors blamed meningitis or encephalitis; no one knew for sure. ‘We have fought together,’ Beauvoir wrote, ‘against the revolting fate that had lain ahead of us, and for a long time I believed I had paid for my own freedom with her death.’ This astonishing sentence – ‘whoah Simone,’ I wrote in the margin – is where Beauvoir ends Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter. It’s one of the most novel-like endings of all her books: best friend dead, first love engaged to someone else, the faith and social class into which she was born abandoned. But Sartre is waiting in the Jardin du Luxembourg to talk about Plato – and a career as a writer and thinker is within reach.

In the epilogue to Force of Circumstance, Beauvoir said that there had been ‘one undoubted success in my life: my relationship with Sartre’. She explained that they had only once, and only for one night, been at odds. They reasoned together, shared the same body of reference: ‘We might almost be said to think in common.’ She added that this might seem to contradict what she says about independence in The Second Sex, but she made a distinction: ‘I insist that women be independent, yet I have never been alone.’ That delicate, perhaps utopian balance – independence not being allowed to cede to loneliness – was present in the way she and Sartre conceived of their relationship from the beginning: theirs being the essential love, they wouldn’t lie to each other about contingent lovers. They would try this ‘lease’ for two years while they were both in Paris, and then renegotiate, in the belief that they would be separated for two or three more years. Beauvoir remembered feeling ‘a flicker of fear’ over this arrangement, a feeling she immediately subdued. Scholars including Toril Moi have seen her acceptance of the pact as a strategy for dealing with her fear of losing Sartre, but she seems to have suffered all the same. Bair says in her new memoir that nearly all Beauvoir’s friends remember her sometimes leaving the café table during evenings with the ‘family’ – Beauvoir and Sartre’s name for the group of ex and current lovers they socialised with – to ‘go and sit alone at another table to consume vast quantities of wine and sob uncontrollably’. Beauvoir herself talks of the jealousy she suffered the first time Sartre took another lover, and of the moment ‘my heart’s old armour of optimism fell away’ when he told her of the weeks he’d spent in New York falling in love with Dolores Vanetti, to whom he would propose marriage. If writing a novel (She Came to Stay) about sharing a lover that ends in the established woman killing the newcomer isn’t a sign of distress, what is? Generations of feminists have asked the question never expressed better than by Angela Carter in the LRB in 1980: ‘Why is a nice girl like Simone wasting her time sucking up to a boring old fart like J-P?’

At the end of the first year of the Sartre-Beauvoir pact – marked by that first experience of jealousy, which she dispelled by walking up and down the Butte Montmartre – Beauvoir was sent to Marseille to teach. Sartre proposed to her so that they wouldn’t have to be separated. ‘I may say that not for one moment was I tempted to fall in with his suggestions,’ Beauvoir writes in The Prime of Life, adding that ‘the task of preserving my independence was not particularly onerous; I would have regarded it as highly artificial to equate Sartre’s absence with my own freedom – a thing I could only find, honestly, within my own head and heart.’ Twelve years later, she wrote about this ‘important decision’ in different terms: ‘I very strongly wished not to leave Sartre. I chose what was the hardest course for me at that moment in order to safeguard the future.’ There is a complex idea of independence here: it can’t be defined by leaving Sartre, and yet it can’t be achieved by staying with him when she wanted to. ‘If any man had proved sufficiently self-centred and commonplace to attempt my subjugation,’ she writes about the fear of abandoning herself to love, a fear that comes up again and again, ‘I would have judged him, found him wanting, and left him.’ Perhaps Beauvoir’s independence was achieved in the way she describes it in The Prime of Life, by working determinedly at her teaching at the lycée during the week and hiking in the calanques and the Côte d’Azur at the weekends, ‘daily and unaided fashioning my own happiness’.

The next year she was in Rouen and Sartre not too far away in Le Havre, where he was beginning to set down the thoughts that would result in Nausea. When they went back to Paris they would meet friends over apricot cocktails to elaborate Husserl’s phenomenology into a philosophy of everyday life. Beauvoir began seven novels in this period, abandoning them all. She feared that the writing life she longed for would never materialise; when she was drunk, she would cry and then argue with Sartre, insisting that drunkenness let her see the truth: ‘the joy of being, the horror of being no more’ (Sartre didn’t agree). She began a relationship with one of her pupils in Rouen, Olga Kosakiewicz (Beauvoir was 27, Olga 17); Olga, the first lover she and Sartre shared, remained a part of the ‘family’ until she died. Around this time, Sartre took an injection of mescaline to pull him out of a depression and found himself trailed by imaginary lobsters. Beauvoir, deeply unsettled, said she ‘preferred the idea of Sartre angling for Olga’s emotional favours to his slow collapse from some hallucinatory psychosis’, though the idea of living in a trio for years ‘frankly terrified’ her. Almost in reply to Sartre’s desire for Olga, Beauvoir took up with one of Sartre’s students, Jacques-Laurent Bost (‘I slept with little Bost three days ago,’ she wrote to Sartre. ‘It was I who propositioned him, of course’), and continued to sleep with him for a decade. Olga, who would hate the way she was written about in She Came to Stay, barely spoke publicly of her relationship with the pair, saying almost nothing to Bair. She soon extricated herself, transferring her affections to Bost, whom she would eventually marry. Bost’s affair with Beauvoir was kept secret from Olga – and omitted from her memoirs, but not from She Came to Stay, a frequent Beauvoirian move.

In 1938, Nausea was published to acclaim (it was Beauvoir who had suggested that Sartre present his ideas in a novel rather than an essay) while Beauvoir’s collection of short stories was turned down twice. She began relationships with some of her other pupils, among them Nathalie Sorokine (who called her ‘a clock in a refrigerator’ for the way she divided her time between her lovers and her work, brooking no deviation), and Bianca Bienefeld, whom Sartre seduced (once Beauvoir had told him how to go about it). He also began a relationship with Olga’s sister, Wanda. Beauvoir told Sartre that the situation had become ‘grimy’: Bianca was dependent and desperate, convinced Beauvoir loved Sartre more than her. Beauvoir admitted that she had behaved disgracefully and encouraged Bianca to put herself at the centre of her own life. (There is a particularly nasty letter to Sartre in which Beauvoir describes Bianca’s ‘pungent faecal odour’ during their ‘embraces’.)

When the war began in September 1939, both Bost and Sartre went into service. Beauvoir fell into a depression, left Paris, came back again. She got used to food shortages, didn’t wash much and waited for letters that inevitably got misdelivered. Sartre broke up with Bianca by letter, exacerbating her distress: ‘I never blamed you for making the break, since after all that’s what I’d advised you to do,’ Beauvoir wrote to him, ‘but I blamed us – myself as much as you, actually – in the past, in the future, in the absolute: the way we treat people.’ In 1993, after the letters to Sartre were published, Bianca wrote a memoir, Mémoires d’une jeune fille dérangée – a riff on Beauvoir’s title. She’d felt abandoned by the couple during the war (she was Jewish) and began to recover only when she married one of Sartre’s pupils, was analysed by Lacan and achieved some distance from the ‘family’. In December 1945, after an evening spent talking to Bianca, Beauvoir was full of remorse: ‘She’s suffering from an intense and dreadful attack of neurasthenia, and it’s our fault I think. It’s the very indirect but profound aftershock of the business between her and us. She’s the only person to whom we’ve really done harm, but we have harmed her.’

Beauvoir was the co-architect of Bianca’s suffering: the women and men who got involved as contingents weren’t fully responsible for what happened to them. The harm to Bianca was lasting and intense, and Beauvoir’s cruelty is difficult to forgive in the woman who would write the ethics of existentialism (Sartre never got that far) and say in her plays, essays, novels and memoirs that reciprocal relationships were what mattered most in life. I struggle with knowing about Beauvoir’s repeated relationships with people younger than and overawed by her, the betrayal, the abandonment. What would be said about her if she were a man in the age of #MeToo? (Sorokine’s mother pressed charges for debauchery on these grounds, and Beauvoir was dismissed from teaching in 1943 by the Vichy authorities, which was seen as a feather in the résistante’s cap rather than a sin against sexual mores.) But Beauvoir never entered into this sort of trio after Bianca; she recognised she had hurt someone she loved; it seems that she was the one to call a halt to the griminess. In The Prime of Life, reflecting on the pact 31 years later, she says: ‘There is no timeless formula which guarantees all couples achieving a perfect state of understanding; it is up to the interested parties themselves to decide just what sort of agreement they want to reach. They have no a priori rights or duties.’ Now we have the letters, the diaries and the testimony of the ‘thirds’, we can see the pact being renegotiated in real time, as they decide what suffering each can bear (Sartre was also jealous, particularly when Olga wouldn’t sleep with him) and allow the experiment in love to play out until it gets to be too much. In certain moods I can agree with Beauvoir that her relationship with Sartre was the greatest success in her life – it was certainly hard-won, which is perhaps what gave it its value.

Since 1941, when Sartre was released from a Nazi POW camp and returned to Paris, the old bande had been meeting in a group they called Socialism and Liberty. They talked, wrote, printed and distributed leaflets, but mostly they lay in wait: ‘If the democracies won, it would be essential for the left to have a new programme; it was our job, by pooling our ideas, discussions and research, to bring such a programme into being.’ But other underground groups were more successful than theirs, and by 1943, Sartre and Beauvoir found themselves reduced, politically, to a state of ‘total impotence’. She held that it was an intellectual’s duty not to write for collaborationist papers, and so she didn’t, but she did accept a job at Radio Vichy producing a programme about medieval music, and she had signed the Vichy oath – declaring she wasn’t Jewish – when still working as a teacher. After the failure of Socialism and Liberty, Sartre and Beauvoir expressed their opposition in their writing: Sartre produced Being and Nothingness, The Flies and No Exit; the ‘grimy’ period earlier in the war had brought Beauvoir the subject of her first novel, She Came to Stay, and during her mornings at Café des Trois Mousquetaires on the rue de la Gaîté she began a second, The Blood of Others, set among Resistance fighters.

When She Came to Stay was published in 1943, followed a year later by her philosophical essay Pyrrhus and Cinéas, Beauvoir’s life as a public intellectual began. After the liberation of Paris in August 1944, the city boomed: ‘So many obstacles had been overcome that none now seemed insuperable.’ Beauvoir might find herself listening to Romain Gary at the Rhumerie, or at a cocktail party with Elsa Triolet and Louis Aragon, or drinking whisky with Hemingway until dawn in his room at the Ritz, or talking to Nathalie Sarraute, or waiting in a cinema queue with Violette Leduc, or sitting on the snowy kerbside at two in the morning while Camus ‘meditated pathetically’ on love. Beauvoir and Sartre set up a journal, Les Temps modernes (named for the Chaplin movie), with Michel Leiris, Merleau-Ponty and Raymond Aron on the editorial committee, and she went to the Ministry of Information to beg for a quota of paper. The Blood of Others came out, the first issues of Les Temps modernes were published, her play, Les Bouches inutiles, was put on, and her stock rose again. She became the literary equivalent of Dior’s New Look, and a tabloid figure: being called ‘la grande Sartreuse’ or ‘Notre-Dame de Sartre’ made her laugh, but she found it ‘repugnant’ to be looked up and down like a ‘dissolute woman’.

She wrote in the mornings in her room in La Louisiane, a private hotel on the rue de Seine, with a cigarette in one hand and a fountain pen in the other, stopped for lunch with Sartre and the family, then returned at 4.30 p.m. ‘into this room that’s still thick with smoke from the morning, the paper already covered in green ink lying on the desk’, to write again before dinner. And she’d found a new question, born out of her admiration for L’Âge d’homme, in which Leiris tried to trace his initiation into manhood, and from seeing the mysterious Lady and the Unicorn tapestries, just brought out from wartime storage: ‘What has it meant to me to be a woman?’ At first, she protested to Sartre that her sex ‘just hasn’t counted’. Look again, he said. ‘You weren’t brought up in the same way as a boy would have been.’ She looked again, and ‘it was a revelation: this world was a masculine world, my childhood had been nourished by myths forged by men, and I hadn’t reacted to them in at all the same way I should have done if I had been a boy.’ In fact, her interest had begun earlier: in 1943, when Paris was still occupied, she had spent time with some of the Surrealist women, now in their forties. ‘They told me a great deal; I began to take stock of the difficulties, deceptive advantages, traps and manifold obstacles that most women encounter on their path.’

The war years were the only time she entertained the idea of herself as a housewife: she records that she scraped the maggots off a joint of pork and made turnip sauerkraut. Now, desperate to travel again, she arranged a four-month lecture trip to America. (Such journeys would be a fixture of Beauvoir’s postwar life: she would visit China, Brazil, Russia, Egypt, Israel, Palestine and Japan as well as making many shorter trips to European countries, spending every summer in Rome.) Sartre had already been to the US, and now Dolores was getting a divorce and coming to Paris. Beauvoir was scared of the depth of their connection; it seemed better for the two women to swap countries. She landed in New York City in January 1947 and went straight out into the ‘supernatural light’ of Broadway, freed from ‘the past and the future, a pure presence’. Vogue threw her a party, the New Yorker described her as the ‘prettiest existentialist you ever saw’ and she lunched her way around Manhattan, becoming close to Richard Wright and his wife, Ellen (left-wing Americans who criticised their country in a way that made you love it more), before taking off for Vassar, then Chicago, California, Texas, New Orleans and New Mexico.

She’d been told to look up Nelson Algren when she got to Chicago, but when she rang a ‘surly voice’ told her she had the wrong number. She rang again, and again the voice said wrong number. She rang a third time; he hung up. After ‘a melancholy supper at a drugstore counter’ she rang a fourth time, this time leaving a message with the operator, and when Algren heard the names of their mutual friends, he at last softened and said he’d meet her in the lobby in half an hour. They spent the evening in West Madison among the ‘bums, drunks and old ruined beauties’ – ‘it is beautiful,’ Simone told Nelson – and then talked about Malraux’s novels until one in the morning with a ‘peroxided blonde’ who ran a shelter for down-and-outs. Beauvoir returned to Chicago at the end of the lecture tour. The first day of her reunion with Algren at his home in Wabansia Avenue was, she explained in Force of Circumstance, ‘very much like the one Anne and Lewis spent together in The Mandarins’, the novel dedicated to Algren: ‘embarrassment, impatience, misunderstanding, fatigue, and finally the intoxication of deep understanding’. The next day he gave her a ‘clunky silver band’, as Bair calls it, a Mexican ring that Beauvoir told her was ‘supposed to be my wedding ring and I am going to be buried with it’. The day he gave her that ring became their anniversary. Her friends in New York warned her that he was ‘unstable, moody, even neurotic’, but she ‘liked being the only one who understood him’. She wept on the plane back to Paris when she found the poem her ‘beloved husband’ had written inside the copy of his book he’d given her, and during her stopover she wrote to him in her idiosyncratic English: ‘I love you. There is no more to say. You take me in your arms and I cling to you and I kiss you as I kissed you.’ Back in France, she moved away from Paris to avoid Dolores, gave up work on her ‘essay on Woman’ and used orphenadrine, a muscle relaxant, to blunt her self-questioning over Algren. ‘Wouldn’t it be better to give up the whole thing?’ she asked herself. But she kept writing to him, telling him that ‘I feel I am tied to you by hundreds and hundreds of ties, and they will never be broken,’ and trying to make him understand that while he would always have the love of his ‘Wabansia wife’, he could never have her life, which was in Paris. By September, she was back in Chicago.

Bair spent seven years talking to Beauvoir about her life and remembers the story of the affair with Algren as the only time she became ‘girlish, flirtatious, gloriously happy, and deeply sad – all in the single telling’. Sometimes it’s hard to remember that this 39-year-old woman writing as ‘your loving frog-wife’ to ‘my own beloved Nelson’ was also drafting The Second Sex: ‘The mornings are so hard, my love, when I open my eyes and you are not there,’ she wrote to him on her return to Paris at the end of September 1947. ‘Last year my life here was full and rich, now everything is empty.’ Although Beauvoir maintained to the last that she couldn’t have left France, I often think she should have: while in love with Nelson she wrote The Second Sex, about falling in love with Nelson she wrote The Mandarins. Why else would you need to be free, if not to do what you want to do? Over the next five years Algren asked her again and again to marry him, and when he realised she wouldn’t, he remarried his ex-wife, rejecting Beauvoir’s offer of friendship: ‘I can never offer you less than love.’ When the remarriage failed eight years later, he visited Paris and they found a sort of harmony again: visiting the Crazy Horse and the Lapin Agile, going to the Musée Grévin and listening to Bessie Smith, seeing Seville and Athens and Istanbul and Marseille. ‘I wasn’t tearing myself to pieces, as I used to, at the thought that our intimacy had no future,’ she wrote in Force of Circumstance; their relationship was ‘completed, saved from destruction, as though we were already dead’. It wasn’t quite dead for him: he was furious about what she said about their affair in her memoirs, writing in Harper’s in 1964 that ‘anybody who can experience love contingently has a mind that has recently snapped. How can love be contingent? Contingent upon what?’ They stopped writing to each other that year, but when Beauvoir was buried, more than twenty years later, she was wearing Algren’s ring, as she said she would.

Ionce went to a fancy dress party as Beauvoir: I wound a black and white scarf round my head as a turban, but people kept asking who I was supposed to be and I kept having to get my copy of Le Deuxième Sexe out of my back pocket to explain. I now think this might have pleased Beauvoir, who didn’t want to be remembered for a hairstyle she’d adopted to hide dirty hair during the Occupation, but had hoped, from the age of twenty and far beyond, ‘to make myself loved through my books’. Twelve years after she published The Second Sex in 1949 she was still receiving letters from women who told her that it had ‘saved me’; psychiatrists, she heard, gave it to their patients. It was the book that brought her the most satisfaction; she was gratified that younger women now wrote as ‘the eye-that-looks, as subject, consciousness, freedom’. (Less pleased were Norman Mailer, whose first wife divorced him after reading it; the pope, who banned it; and François Mauriac, who told a contributor to Les Temps modernes that ‘your employer’s vagina has no secrets from me.’)

The Second Sex germinated in conversations with Sartre, was changed by Beauvoir’s experience of love with Algren, owed a lot to the understanding of the US civil rights movement she gained from Richard Wright, and was given its title by Bost. It’s a long book with a simple proposition, one of those elegant thoughts it’s both easy to remember and impossible to exhaust: ‘One is not born but rather becomes a woman.’ The idea is still alive for me: if one becomes a woman, I reason, then it is right for trans women to be considered women; if you want to recentre black women’s voices, then you pay attention to the particularities of their becoming. And it is a hopeful one: women are trapped, mutilated (one of Beauvoir’s favourite words), complicit, steeped in bad faith not because that’s their nature but because that is how the world has schooled them – or, rather, not schooled them. The world has, can and must change.

It’s also a curious book, with a strange history. I was struck by the fact that although its structure can be laid out logically on a contents page – the first volume covers what has been said about women by biology, psychoanalysis, historical materialism, history and literature; the second goes through the ages and archetypes of woman before finally considering what it might take for them to become independent – it reads as if it was assembled from personal experience: Beauvoir’s travels, her discussions, her reading and her understanding of existentialism. It seems homemade, like a patchwork quilt. She calls the woman in love a jailer, a paranoiac, a slave, a person involved in a desperate psychological attempt to ‘survive by accepting the dependence to which she is condemned’; yet she also imagines an ‘authentic love’, ‘a human interrelation’ founded on accepting the other ‘with all his idiosyncrasies, his limitations and his basic gratuitousness’. (I think of Beauvoir saying she wasn’t offended at Algren’s ‘bluntness’ when he was asked about the US publication of The Mandarins: ‘I knew all about his moods.’) For a book that invigorated a liberation movement, it spends a great deal of time elaborating on the ways woman is everywhere in chains; independence is only glimpsed. The intellectually free woman fears losing love, so makes ‘a show of elegance and frivolity’ instead of ‘naturalness and simplicity’; she cultivates competence when ‘discussions, extracurricular reading, a walk with the mind freely wandering’ would do more to encourage originality; she is new to the country, and so is ‘afraid to disarrange, to investigate, to explode’. The Second Sex has sold a million copies in English, but Anglophones have only been able to see it cloudily: the first silently edited English translation was made in 1953 by a zoologist who didn’t know philosophy; the new one, first published in the US in 2009, was made not by Beauvoir scholars but by translators whose previous work included cookery books. But it is, for better or worse, where modern feminism begins, and though I long for a world where it is no longer useful, I use Beauvoir’s application of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic – woman is doubly oppressed, first because she’s a slave and second because she works to identify with her master’s view of her as a slave – most weeks, and on bad weeks most days.

Giving up Algren, Beauvoir gave up on love. ‘I’ll never sleep again warmed by another’s body,’ she said to herself, and tried to accept it. ‘I suddenly found myself on the other side of a line,’ she wrote in Force of Circumstance. ‘I stood there, bewildered by astonishment and regret.’ She learned to drive; on a spring road trip to Provence, behind the wheel on her own for the first time, she felt as exhilarated as she had when walking in Marseille as a young woman. She finished the enormous novel that was becoming The Mandarins, giving herself the ‘pleasure’ of transposing into ‘a fictional world an occurrence’ – her time with Algren – ‘that meant so much to me’. One of the curious things about Beauvoir’s work is the way she mixes genres: her novels have the tang of memoir, her memoirs have the finish of a novel, her essays have the tone of conversation, her conversation has the severity of a lecture (as you can see on YouTube, she never smiles or uses a plain French word when a recondite one would do), her letters have the feel of pillow talk. This has often meant that her novels look more like romans à clef than they are, and that her memoirs are taken as gospel. (It has led to funnier misunderstandings too: when Beauvoir published ‘The Woman Destroyed’ in Elle magazine, hundreds of readers wrote in to say how sorry they felt for its protagonist, whose husband had left her. Beauvoir had to explain that she had intended merely to alert them to the danger in not having resources of your own.) It’s as if she pursues the idea first, then bends the rules of the genre to fit what she has to say. She’ll tell the reader she can skip the account of her travels to Brazil if she likes, or let her semi-fictional characters talk for pages before they do anything. Over time, her sentences became plainer and her turn of phrase more vivid. As a body of work hers feels accidental, prolix and messy: not the work of a concrete block, but of a woman.

In 1954, when she was 46, The Mandarins won the Prix Goncourt, and Beauvoir became only the second woman the jury could agree on in fifty years (Elsa Triolet was the first). She refused to ‘exhibit herself’ to the press, skipping the traditional scrum at Drouant for lunch with members of the family, including Claude Lanzmann – her new lover, the first, contingent or essential, she’d moved in with. She credited Lanzmann with having ‘freed me from my age’, and he encouraged her to keep going on The Mandarins; Beauvoir would lend him money to begin filming Shoah. Sartre’s role in her life had changed: they still worked together in the afternoons, and still summered together in Rome, but since her time with Algren she had a new freedom from him. After winning the Goncourt (and buying her first apartment with the royalties) she began writing her memoirs, in which Sartre makes many comic appearances: he dresses up in drag and is pursued by an American lesbian, steals a skull from an ancient ossuary, rolls down the slope he’s supposed to be sleeping on, encourages Simone to overtake dawdling Italian drivers (‘Pass him, go on, pass him!’), tries sashimi for the first time, then Japanese whisky for the first time, then can’t eat anything for two days. Some complained that she was demeaning a great man, but Beauvoir, true to form, thought that the telling of these things only made him more loveable.

The end of her life was marked by intolerable losses and a resurgence of political activism. The Algerian war soured her view of France, and brought her out onto the streets again and again. She saw herself differently as she aged: ‘I loathe my appearance now,’ she wrote at 55, and wrote a book, Old Age, in the manner of The Second Sex. As she approached sixty, Lanzmann moved out, though he remained part of the family; five years later, Beauvoir’s mother died. Beauvoir hadn’t been close to her mother since her late teens, when she broke with Catholicism, but the experience of caring for her during her six-week illness, while concealing from her the diagnosis of untreatable intestinal cancer, brought about an intense period of grieving – and the short, brutal and beautiful memoir A Very Easy Death. Françoise de Beauvoir had ‘lived against herself’, continually rebelling ‘against the restraints and privations that she inflicted upon herself’. Her life could have been used as an example of a woman oppressed by society, living proof of the arguments put forward in The Second Sex. But at the end things became tender and simple, and Beauvoir could make her happy by feeding her tea with a spoon, crumbling a bit of biscuit into each spoonful. After her mother’s death, Beauvoir looked again at a photo of the 18-year-old Simone with the 40-year-old Françoise around the time they broke with each other: ‘I am so sorry for them – for me because I am so young and I understand nothing; for her because her future is closed and she has never understood anything.’ It was at this point that she became close to Sylvie Le Bon, a philosophy student 33 years her junior, who had written to her in admiration a few years earlier and was studying at the Normale (now open to women). When Beauvoir broke down after seeing her mother in a hospital bed for the first time, Sartre had helped her analyse her feelings, but he hadn’t dried her tears. Sylvie was different: she accompanied Beauvoir on trips to Rome and New York, did her shopping, watered down her whisky, and eventually became her literary executor. There were other rumours too. When Bair asked Beauvoir about the nature of their relationship, she exploded: ‘We are not lesbian! … Oh sure, we kiss on the lips, we hug, we touch each other’s breasts, but we don’t do anything … down there! So you can’t call us lesbians!’ You can take the girl out of the Catholic bourgeoisie, but you can’t take the Catholic bourgeoisie out of the girl.

Both Beauvoir and Sartre supported the occupation of the Sorbonne in 1968, wandering the corridors, joining in the discussions about the Palestinian question. Beauvoir was hopeful: ‘For the first time in 35 years the question of a revolution and of a transition to socialism had been raised in an advanced capitalist country.’ It was what she had been waiting for since Algeria. As the événements faded, she became involved with feminist organising. The Mouvement de libération des femmes (MLF) was born in August 1970, when nine women including Christiane Rochefort and Monique Wittig attempted to lay a floral sheaf for the unknown soldier’s wife at the Arc de Triomphe. Their bedsheet and bamboo banners read: ‘Il y a plus inconnu que le soldat inconnu, sa femme’ (‘more unknown than the Unknown Soldier is his wife’). In 1971, in support of the MLF’s campaign for free abortion, Beauvoir signed the ‘Manifeste des 343’, declaring in that week’s Nouvel Observateur that, along with Catherine Deneuve, Delphine Seyrig and Marguerite Duras – as well as Olga, her own sister, and dozens of secretaries, office workers and housewives – she had had an abortion. She marched on the Assemblée Nationale with the MLF, let them hold meetings at her flat, read the SCUM manifesto, The Feminine Mystique, The Dialectic of Sex, Sexual Politics and The Female Eunuch, and changed her position. In The Second Sex in 1949, she had written that ‘by and large, we have won the game.’ Now, after 1968, she declared ‘myself a feminist. No, we have not won the game: in fact we have won almost nothing since 1950.’ She saw that women were primarily devoted to ‘the act of wiping – of wiping babies, the sick, the old’; she saw that a socialist revolution that didn’t bring women along with it wasn’t worthy of the name (in this she admired Juliet Mitchell’s analysis in Women’s Estate); she wished ‘for the abolition of the family’, calling herself an ‘activist for voluntary motherhood’, but didn’t want to be shut up in a ‘feminine ghetto’ and barred from having relationships with men. By 1975, Simone Veil had introduced a modern abortion law in France, and Beauvoir moved on to try to change the laws governing divorce. She also edited a column in Les Temps modernes called ‘Everyday Sexism’.

Sartre died in April 1980. Beauvoir had to be stopped from embracing his corpse – his bedsores were gangrenous – but when the nurse found a sheet to drape over him she climbed up anyway, fell asleep on his dead body and stayed there until morning. The thousands of followers behind his flower-piled Citroën hearse brought Montparnasse to a standstill; Beauvoir washed valium down with whisky to get through his funeral and had to be given a chair when she got to the graveside. She contracted pneumonia a few days later, and while she was in hospital they found cirrhosis and motor neuron damage; it was months before she regained balance mentally and physically. Her last volume of memoirs, All Said and Done, isn’t arranged chronologically, but according to the things she lived for: relationships and friendships first, then writing, reading, movies, music and painting, then travel and finally politics. (My favourite part of it is her list of dreams: it’s comforting to know that she had a recurring dream in which she couldn’t find a loo.) Those things brought her back to life: to her Sylvie was like Zaza reborn, or herself reincarnated; she made a last trip to New York, where she visited Kate Millett’s feminist Christmas-tree-growing artists’ commune; she wrote about Sartre’s death and collaborated with Bair on her biography; she campaigned for a law against sexism and gave a series of interviews to Alice Schwarzer about her feminism. She took to receiving people at home in a red bathrobe, like the one her mother had worn during her last illness. When she was taken into intensive care with another bout of pneumonia in spring 1986, she tried to persuade her nurse not to vote for Jean-Marie Le Pen. She died on 14 April. At her funeral, of all the passages of all the books she’d written, Lanzmann chose to read the last paragraph of Force of Circumstance:

I loathe the thought of annihilating myself quite as much now as I ever did. I think with sadness of all the books I’ve read, all the places I’ve seen, all the knowledge I’ve amassed and that will be no more. All the music, all the paintings, all the culture, so many places: and suddenly nothing. They made no honey, those things, they can provide no one with any nourishment. At the most, if my books are still read, the reader will think: There wasn’t much she didn’t see! But that unique sum of things, the experience that I lived, with all its order and all its randomness – the Opera of Peking, the arena of Huelva, the candomblé in Bahia, the dunes of El-Oued, Wabansia Avenue, the dawns in Provence, Tiryns, Castro talking to five thousand Cubans, a sulphur sky over a sea of clouds, the purple holly, the white nights of Leningrad, the bells of the Liberation, an orange moon over Piraeus, a red sun rising over the desert, Torcello, Rome, all the things I’ve talked about, others I have left unspoken – there is no place where it will all live again.

From the grave, Beauvoir clinches the argument. Life isn’t supposed to be lived as some kind of example to others; all it is, all it can be, is a crashing together of moments. Beauvoir couldn’t come again – and thank God. But I have my heroine back, freed from her concrete block.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.