The Jalori Pass in Himachal Pradesh, northern India, is ten thousand feet above sea level: there was snow on the ground when I crossed it on foot in May 1982, on a trek in the Himalayas with a friend. The route took us down the side of a mountain to the resthouse we were aiming for, a single-roomed stone building, maintained by an absent housekeeper. Apart from four bare bedsteads, there was nothing inside except an old notice hanging on the wall. It showed the silhouettes of many of the larger creatures that lived in the jungle below. Panthers and tigers headed the list: there were birds and reptiles too. The words ‘Live and Let Live’ ran across the top of the notice, followed by ‘Shoot Only to Kill’. The next day, we walked into the jungle. The foliage was impressive, but it was the only thing left to see: everything else had been looted.

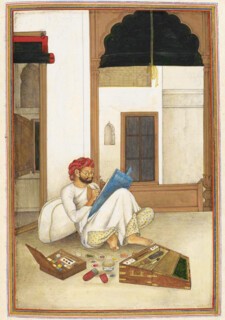

Forgotten Masters, an exhibition of works painted by Indian artists for East India Company officials, currently on display at the Wallace Collection (until 19 April), shows, among other things, India before the carnage of the 19th century (the word ‘loot’ comes from the Sanskrit ‘lunt’, and was adopted by the British in the late 18th century). The images of birds, mammals and plants are the outstanding exhibits. Almost nothing is known about the artists; even their names very often went unrecorded. The patrons have clearer identities. One, Claude Martin, was a vinegar distiller’s son from Lyon, who joined the Compagnie des Indes only to desert the French for the British East India Company. He made a fortune – exactly how hasn’t been established – and built himself palaces, amassed a large library and created a menagerie in Lucknow, which he employed a team of artists to paint.

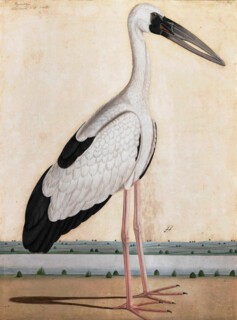

For Mughal rulers, menageries represented both status and lineage – an inheritance amassed by their ancestors. The prohibitive cost of maintaining one meant they continued to be a sign of wealth for the Europeans in India who adopted the practice. Having your menagerie painted was also expensive: Martin imported more than 17,000 sheets of fine watercolour paper. Indian artists worked in traditional stone-based pigments and used Mughal techniques, but took European natural history images as their models. Shaikh Zain ud-Din, one of the earliest and best practitioners of this new ‘Company style’, was employed by Mary Impey, the wife of a Calcutta Supreme Court judge, to make paintings of her birds and animals. The project took five years and by the time the Impeys returned to London she had hundreds of meticulously painted images, many of them not only true to life but also life-sized.

The ornithological pictures on display at the Wallace resemble those of John Audubon’s Birds of America. Their common denominator is the 11-volume Histoire naturelle des oiseaux (1771-86) of Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, illustrated by François-Nicolas Martinet and famous across the late 18th-century world (Martin and Impey both had copies). A painting by ud-Din of an Indian Roller bird perched on a sandalwood branch illustrates the connection. As the catalogue note explains, the Roller’s name comes from the twists and turns it makes to evade its captors. ‘The perching bird is depicted preening its feathers … allowing the artist to render … the unfurled winged plumage in its intense gradations of turquoise, indigo and purplish tones.’ Buffon writes that the Indian Roller is thought to have the species’ biggest wingspan: ud-Din’s bird may be preening but it’s also showing off the size of its wing. It’s a remarkable interplay of European descriptiveness and Indian luminescence.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.