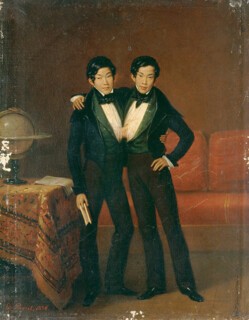

In 1824, a Scottish merchant called Robert Hunter was sailing down the Mekong when he saw what Yunte Huang describes as a ‘two-headed Hydra-like creature’ climbing into a dinghy. On closer inspection, Hunter was astonished to discover ‘not some amphibious reptile’ but two identical young boys connected at the chest by a thick band of flesh. He had been on the lookout for new ways to make money in Siam; that summer’s day, he found one in the body of the 13-year-old twins.

Chang and Eng’s family belonged to a large Chinese community in Siam, and were known locally as the ‘Chinese twins’. As the boys grew, the band connecting them stretched to five and a half inches, allowing them to walk, however haltingly, and to swim. They would probably have become fishermen, like most of the men in their family, if not for the opportunistic Hunter. After years of effort, the merchant, together with the American ship’s captain Abel Coffin, gained royal permission to take the brothers on a performance tour of Europe and America. Chang and Eng signed a contract on 1 April 1829: it promised to pay them a wage, all their expenses and stated that a return trip to Siam would be arranged within five years. Chang and Eng, illiterate youths far from home, controlled by adults who viewed them as material goods, were essentially treated as slaves by Coffin and Hunter. Coffin brought embalming fluid along to safeguard his investment, intending to display the twins dead or alive. ‘I hope these will prove profitable as a curiosity,’ he wrote to his wife, Susan, who eventually undertook much of the daily work of managing the twins.

Onlookers flocked to view the Siamese Twins and paid a high price – fifty cents or the equivalent – for the privilege. At their Boston debut in August 1829, both their foreignness and their conjoined bodies were emphasised: Chang and Eng were dressed in ‘native’ costume which exposed the band that connected them and posed in front of a painted scene evoking the Orient. Newspaper articles, broadsides, posters, handbills, editorials, lithographic portraits and satirical poems were widely distributed, encouraging everyone to see the lusus naturae. One account from the 1830s reassured women and children that ‘there is nothing whatever offensive to delicacy in the said exhibition.’

As part of his publicity campaign, Coffin had the twins examined by American and British doctors who were eager to get their hands on such unusual human specimens. Everyone wanted to know whether Chang and Eng could be separated: the prevailing medical opinion was that it would probably kill them. The combination of exhibition, medical examination and publication dominated the twins’ daily existence in their first years of nearly constant travel in America and Europe. Angered by their treatment, when they turned 21 the twins successfully plotted to leave the Coffins and strike out on their own. Susan Coffin was outraged. She wrote to the twins repeatedly, pleading her love for them and threatening to take legal action against them. Chang and Eng were unmoved. Their response, taken as dictation by their former manager Charles Harris, was: ‘let Mrs C. look into her own heart and they feel confident she will discover that the great loving & liking was not for their own sakes – but for the sake of the said Dollars.’ By 1839, with more than $10,000 in savings, the twins decided to find a way of making money that did not require them to display themselves. One astonishing aspect of the always remarkable story of Chang and Eng is that they were granted American citizenship although, according to the 1790 Naturalisation Act, they did not qualify because they weren’t ‘free white persons’. Despite this, their petition was granted by a court clerk who knew them well. They settled in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where they had a large and comfortable house built, chose a surname – Bunker – and set about finding wives.

That the twins might marry seemed impossible to everyone apart from the brothers themselves and the local sisters, Sarah and Adelaide Yates, who accepted their proposals – much to the horror of their parents. The two couples were married in April 1843 and returned home, where an extra-wide bed awaited them. The newspapers were filled with speculation about and condemnation of what went on in that extra-wide bed. ‘When a conjoined twin has sex with a third person,’ the ethicist Alice Dreger asked recently, ‘is the sex – by virtue of the conjoinment – incestuous? Homosexual? Group sex? Well, it definitely is sex. You can tell because everyone wants to talk about it.’ Abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison saw the marriages as evidence of the depravity of slave states. How the twins and their wives reacted to the curiosity about their private lives is unknown. By one measure – fertility – the marriages were successful: between them, Chang and Eng Bunker fathered 21 children. Eventually, after they moved to a large farm in Surry County, the twins organised a system to preserve marital and fraternal harmony: three days in Chang’s house during which time Chang made all decisions, and then three days in Eng’s house, where he was the master.

During their years as performers, particularly in the North and in Europe, the Bunkers’ racial otherness seemed to increase their freakishness. The exhibition of native people from around the world at circuses, museums, theatres and world’s fairs was thought to provide the physical evidence for racial hierarchies. In the American South, however, the twins’ race was regarded differently. Chinese Americans and Asian immigrants in general were rare, and while not exactly white, the twins were certainly not black. Although always objects of curiosity, they were essentially left alone by their neighbours to work their land, bring up their children and improve their property – using the labour of enslaved men, women and children. Within just a few years of their marriage the twins owned 18 slaves.

As Yunte Huang makes clear in his new biography of Chang and Eng, the Bunkers play a much more significant role in American history than simply as sideshow freaks; their lives and afterlives illustrate the ways difference was described, denigrated and negotiated at various significant cultural moments. Their unique bond became a perfect symbol of dependence, unity and brotherhood as well as freakishness, and ‘Siamese twins’ swiftly became shorthand for inseparable unions of various kinds. The term was included in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1829 and in the second edition of Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language (1840). Early promotional publications linked the conjoined twins with the motto of the United States – ‘United We Stand’ – both humorously and ironically, yet at the same time closely relating the foreign lusus naturae with the nation. In the 1860s, as the Union – often romanticised as a family in which brother was pitted against brother – was threatened and even temporarily dissolved, their connection was used for a different political purpose. During the Civil War and the Reconstruction, the tenor of political cartoons and commentary changed again, with some using the idea of the Siamese Twins to symbolise objectionable linkages such as miscegenation, or expedient unions such as those between previously opposed political running mates.

The twins cast their lot, ideologically and financially, with the Confederacy. During the war they were taxed and blockaded, and looted by deserters. Both sent their eldest son to fight for the cause. Although the boys returned to the family after the war, there was little to celebrate for the Bunkers. Their slaves were free, their Confederate notes were worthless, and their very large family was hungry. The brothers decided that the easiest way to make money was to return to exhibiting themselves. Although Chang and Eng distrusted and disliked P.T. Barnum – the feeling was mutual – they joined his 1868 British tour, accompanied by two of their adult children and Anna Swan, a ‘giant’ more than seven feet tall.

Although independent, literate family men, naturalised American citizens and landowners, in many respects little had changed for Chang and Eng when they returned to touring after the Civil War. But if the mechanics of these tours remained much the same, their reception was not. British and American papers followed the twins, dismissed their performances as aggrandised begging and seemed often to disapprove of the display of human oddities. There was, it seemed, little to be learned from them – at least until their deaths. On the way back from their 1870 European tour, Chang suffered a stroke that paralysed his left side. The twins lived quietly with their families for the next few years until Chang’s death on 17 January 1874. When Eng realised what had happened to his brother, he responded: ‘Then I’m going too.’ He died a few hours later.

With the deaths of the original Siamese Twins, aged 62, the next phase of obsession with their valuable body could begin in earnest. The sideshow came calling once again as did its distant cousin, science. Strangers wrote to the widows offering large sums of money for the body; the Philadelphia College of Physicians made a case for exhuming it for autopsy. Given that the twins had so often availed themselves of the services of medical professionals, it was suggested, they were duty-bound, in death, to pay for those services. The widows agreed to the autopsy but stipulated that the twins must not be separated and that any study of the ligature must not damage it or be visible from the front. The findings were reported in the Philadelphia Medical Times and widely published. The Bunkers’ body and their lives were once again the focus of intense scrutiny. Chang’s cause of death remained unclear, but the surgeons determined that Eng had died of fright. The liver – William Harvey’s ‘noble organ’ – was discovered to be the key to their inseparability. Science having finished with them, the twins were sewn up minus liver, lungs and entrails, and shipped back to North Carolina.

Huang compares the 19th-century medical theatre with the freak show, seeing both as spaces designed to pathologise the displayed subject. We have not lost our fascination with conjoined twins, yet in the 21st century, we ask different questions about them. Those in the news are almost invariably infants and, typically, separation is the goal. Celebrity awaits successful surgeons, including Ben Carson, who after splitting German twins joined at the back of the head went on to give up medicine to write bestsellers, run for president, and now serves as Trump’s secretary of housing and urban development. Chang and Eng can now be found at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, where conjoined twin cookie cutters are available in the gift shop. They perform in the medical theatre through their anomalous liver, floating in faintly glowing liquid. Mounted above the liver is their plaster death cast, which shows their neatly combed hair, sutured naked chests, crooked overbites and the band that joined their destinies in life and in death.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.