Assiduously and without much constraint, he conditioned his personality, making it as impenetrable and resourceful, as submissive and difficult, as it had to be for the sake of his mission.

Walter Benjamin, ‘On the Image of Proust’

To create in myself a nation with its own politics, parties and revolutions, and to be all of it, everything, to be God in the real pantheism of this people-I.

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

It is the first or Christian name that counts, that is what makes one be as they are.

Gertrude Stein, writing about Ulysses S. Grant

In autumn 1981, hot new act Prince was offered two nights at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum supporting the Rolling Stones. His first impulse was to turn the gig down flat. The Stones had a new album (Tattoo You) to plug; the tour would eventually bring in $50 million in ticket sales, the largest US gross that year. Still, there was a vague sense that frisky young Prince – the latest reincarnation of the R’n’B acts the Stones venerated and in some sense owed their existence to – was being used as a heart-starter, to angry up the old (thirtysomething) troupers’ blood. As Jason Draper puts it in Prince: Life and Times, ‘the average Rolling Stones fan still rode the coat-tails of 1970s rock ’n’ roll, about which everything was neatly defined. Men played guitars and slept with women, who were submissive and did what they were told.’ In contrast, very little about Prince and what he might do next seemed at all ‘neatly defined’. But he had his own new album to plug (called, with extrasensory irony, Controversy) and owed quite a lot of money – and gratitude – to his label, Warner Brothers: the sales of his previous three albums hadn’t met expectations, and there was a feeling that Controversy was make or break. In the end, swayed by his hypo-sharp management team, Prince took the gig.

It didn’t go well. On the first night, 9 October, Prince and his band, the Revolution, barely made it through four songs before getting booed offstage. (Accounts differ, some of them wildly, but it seems to have been one track in particular, ‘Jack U Off’, that triggered most of the derision and homophobic barracking.)1 The rest of the band were game to push on, but Prince fled home to Minneapolis in a funk. If he was angry, it was perhaps most of all with himself: at some level he must have suspected something like this might happen. It had only been two years since Disco Demolition Night, when a shock jock and ‘anti-disco campaigner’ had blown up a crate filled with soul and dance records in front of fifty thousand baseball fans at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. At the opening of the 1980s, pop music was still more or less a segregated thing in America.

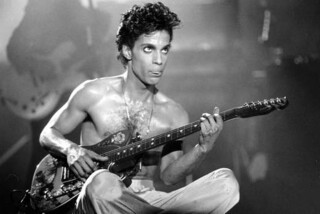

The second show was scheduled for two nights later. Prince’s manager and his guitarist and eventually Mick Jagger himself all got on the phone to lure the tiny man-diva back. It worked. But news of the previous flame-out had spread, and the audience came prepared. Prince took to the stage flaunting his trademark look: high-heel boots, thigh-high aerobic stockings and a pair of tight, velvety, minimalist briefs. (He very conspicuously had not opted for a bikini wax.) Apart from the matelot’s scarf round his neck, the rest was his lithe, black, naked bod. (For comparison, on this stretch of the tour Jagger mostly wore jerseys representing local American football teams.) Prince’s biracial, polysexual band likewise came off as a distinctly queer sight in this locale. They were everything that some sections of the LA rock audience despised: disco beats, cross-dressing, New Wave poseurs, aloof and bony synthesiser muzik. The crowd had a collective meltdown. ‘Fruit, vegetables, Jack Daniels, and even a bag of rotting chicken came flying through the air at the group,’ Draper writes.

In 1981, Prince was an uncomfortable reminder of what lay under the global Good Old Days schtick of the kohl-eyed Stones: an ambiguously inviting/inciting body of colour. Another black innovator stepping up to ‘support’ another bunch of blithe white minstrels. Many inside Prince’s camp saw the Stones gig as a turning point. Already known as something of a control freak, Prince would make sure he was never put in a similar position again – not onstage, not in the media, not in a recording studio, not in any boardroom.

If Prince had died or disappeared in 1989, he would have left behind one of the all-time perfect bodies of work. Dirty Mind (1980) to Lovesexy (1988): a dazzling yet subtle engagement ring offered to the world. In those glory years Prince was, alongside Madonna, the most fascinating pop star alive. A black R’n’B artist who juggled shiny white pop signifiers; a self-amused imp who had us follow his playfully dense personal mythology from work to work, never knowing what we might find next time round, in what form he would return, sometimes mere months later. Dirty Mind in no way predicts Around the World in a Day (1985), which in no way predicts Parade (1986), which sounds nothing like Lovesexy. Prince snuck wild swells and shady undercurrents into mainstream pop, with Janus-faced hits like ‘When Doves Cry’, ‘Little Red Corvette’ and ‘Raspberry Beret’. His first two albums, in the late 1970s, had given no real hint of what was to come. After that shaky start, it was the deus ex (hit) machina of MTV that was the key, as it was for Madonna and Michael Jackson. People of a certain age will never forget the lush, melodramatic promo for ‘Purple Rain’ and the cheeky, pared-down video for ‘Kiss’.2

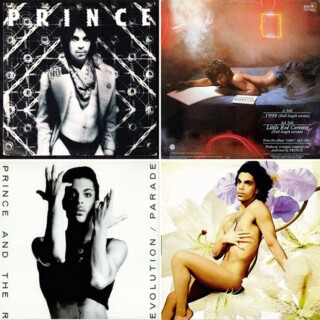

How did he get away with some of this stuff? Controversy came with a full-colour fold-out poster of Prince posing two-thirds naked in the shower. The water drip-drops from his zig-zag briefs; behind him, discreetly positioned on the bathroom wall, is a crucifix. On the sleeve of 1999 (1982) he reclines naked like a Playboy centrefold, in a neon-dappled boudoir. (His hobbies include horse riding, watercolours and pop eschatology …) On the sleeve of Dirty Mind he wears little more than a jacket, those briefs again, and a street hustler’s determinedly blank gaze; a tiny black and white badge on his lapel says ‘Rude Boy’. (Yes, we see.) Looking back, two things strike you. First, even before Madonna, he was posing as an aggressively passive sex object. (These are images that say: ‘You think you know whose tongue is in whose cheek, here, but you really don’t.’) Second, that self-consciously blank gaze, deployed time after time. Look at how expressionless he is in those shots. Has he merely composed his face or is he wearing it, like a mask? Regardless, these early portraits disclose an everyday kid, someone you might see around the neighbourhood, not the flawless no-hair-out-of-place Prince of later years, embalmed inside a pastel armour of good taste, every last bit of skin hidden behind boots, suits, gloves, shades, neo-pimp hats.

Prince always insisted he was drug-free, but by accident or design his 1980s aesthetic chimed perfectly with the first slowly spreading ripples of Ecstasy in transatlantic pop culture. From Dirty Mind to Around the World to Lovesexy we can map the progress of a new form of pop/soul/other music, ambiguously druggy (‘This is not music, this is a trip!’) and strangely clear-headed; deliriously erotic but faux naive. Early profiles emphasised an odd mix of confidence and awkwardness: this postmodern Prince was softly spoken, with a tendency to blush; he promised phallic joy but wore thick lisle tights and high-heel boots. His friends and co-workers reported how seldom he slept. The result is like something intuited in a lucid late afternoon dream: ‘I was dreaming when I wrote this/Forgive me if it goes astray.’

The Revolution weren’t a classic funk band either, more a sonic Frankenstein welded together in the sort of nightclub where the DJ alternated joy-to-the-world disco and snotty, punch-drunk New Wave. The line-up included a geeky white dude in joke-shop doctor’s scrubs, a muscly black guy with a dyed mohican, and two unlikely-looking white women (lesbians to boot, it turned out). Prince was having big fun with the play of appearances, abandoning strict reverence to any supposedly ‘authentic’ truth of what it is to be black, or male, or soulful.

Race isn’t the only way to make sense of Prince, but to try and make sense of him without it is a truly forlorn hope. Yet, to my knowledge, the only critic who ever tackled the subject head on is the writer Carol Cooper, an African American woman who had also worked in the music industry. In an astute piece for the Face in June 1983 (it includes a wholly imaginary Q&A with Prince which was still being quoted as fact thirty years later, so acute was her impersonation), Cooper wrote about the way black artists routinely have to ‘exaggerate and contort’ their image in order to get media coverage. The ‘doe-eyed sex freak’ was, she noted, just one of many eye-catching constructs the canny Prince used to garner his share of attention.

Cooper had the requisite sense of what black people were made to go through at that time just to be accepted at all, never mind on a grander, world-conquering scale. She had a beady eye (as Prince did) for the apparently trivial details, coded put-downs and subtle sightlines of race politics that usually went unmentioned. Black success is different from white – always the extra pressure of having to be a ‘role model’. No matter what you do, you never please everyone. If you embrace global success you’ll get poison about forgetting your roots; stay close to home and you’ll be criticised for lacking ambition. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t – as the Rolling Stones gig proved. Prince’s black audience had little interest in guitar-led stadium rock anthems, while the rock fans were too hidebound to get that Prince was writing far better songs, and playing far heavier rock, than their profit-eyed, zoned-out heroes.

Prince was born on 7 June 1958 in Minneapolis. His father, John L. Nelson, was 42 at the time; his mother, Mattie Shaw, was 25. His first name was the one his father performed under in a local jazz combo: Prince Rogers. During Prince’s teenage years it was a volatile household. Listening to ‘When Doves Cry’ is like eavesdropping on an analytic session: ‘Maybe I’m just like my father, too bold … Maybe I’m just like my mother – she’s never satisfied.’ A song riven with doubt about loving the other, and the other’s love: ‘How can you …? Why do we …? Maybe you’re …’ The story goes that the priapic young Prince was thrown out of his father’s house for ‘entertaining’ girls in the basement music room. And while John Nelson wasn’t perhaps as cruelly overbearing as some soul music patriarchs (Marvin Gaye Snr, Joe Jackson), he does seem to have been a man who raised the Bible high at home but happily provided musical accompaniment for the strippers in the Minneapolis tenderloin.

In early interviews, Prince would tease with hints about his childhood: that his mother showed him Playboy magazine in lieu of sex education; that he indulged in near incest with his half-sister. He was forever blurring the question of what race he and his parents were, exactly.3 This was the time of Tipper Gore and her campaign to force record companies to place ‘parental warning’ stickers on their devil’s-spawn LP sleeves. (The kind of publicity most young rock acts dream of.) Gore wasn’t provoked by some sleazy heavy-metal outrage: the offending party was Prince, and in particular a track called ‘Darling Nikki’ on the otherwise poptastic Purple Rain soundtrack, in which the titular character is found ‘in a hotel lobby, masturbating with a magazine’. It’s also the only weak song on an otherwise flawless album, a track I routinely skip; even at the time it felt tacky, a self-parodic caricature of the exquisitely economical songs on Dirty Mind. When you play Dirty Mind now – and this also applies to 1999 and Purple Rain – what’s really notable is how stark and minimal and unfussy the arrangements sound: Prince had already taken onboard the new-fangled synthesiser technology, giving his ‘dirty’ schtick a rivetingly clean and sprightly sound.

When I first saw the Purple Rain movie in 1984, I thought: what a disaster, this will surely sink him. I was, of course, 100 per cent wrong. It was a classic example of an audience going crazy for something they had no idea they wanted until it was sitting right in front of them. Purple Rain was a huge success, delighting Prince’s paymasters at Warner Brothers and making future deal-making a lot easier for him. On a symbolic level, Purple Rain presented as a black overhaul of white movie clichés: moody boy and his motorbike; the Girl You Could Maybe Truly Love v. the girls who play dangerous games; Oedipal tensions; street-life temptations. (Between them, Purple Rain and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1983 film Rumble Fish supplied enough new visual-pop clichés, black and white, to keep MTV stoked for some time.) On the Purple Rain soundtrack, ‘Let’s Go Crazy’ is, like the film itself, a spunky celebration of familiar tropes: ‘Kids! Don’t listen to those ugly straights! They’re just jealous of us cool kids!’ It’s in the music’s rainbow sounds that everything is going on. Across the album, Prince’s voice is set in a frame that’s neither straightforward soul music nor rock ’n’ roll. It’s an elegant hybrid, where clingy opposites attract: acoustic guitar with classical strings on ‘Take Me with U’; wobbly church organ with latest-thing synth drums on ‘Let’s Go Crazy’. In ‘The Beautiful Ones’, Prince’s voice wakes as a sleepy croon, but by song’s end it’s a mess of jagged shards on the edge of pure noise. We’ve all heard the epic title track so many times it’s easy to miss how unusual it really is. The casually strummed chords of the opening, and the long mournful guitar solo near the end, discreetly call up the ghost of another black psychedelic epic, Funkadelic’s ‘Maggot Brain’. And rather than ending on a squalling climax, as 99 per cent of rock ballads would, ‘Purple Rain’ slowly ebbs into nearly two minutes of wistful fugue, until there’s only the sound of delicate strings and unfiltered ambient noise. (It’s the subcortical memory of details like this which maybe predisposes some of us to find Prince’s post-1989 work a bit meh in comparison.)

The whole 1980s catalogue is wonderful, but for me the apotheosis isn’t the usual choice, Sign o’ the Times (1987), but Parade (1986). It has everything: joy and sadness, get-down and wistfulness, mourning and melancholia, group funk and Debussy interludes, echoes of Ellington, Joni, film music, chanson. It’s a perfectly realised whole. The opening rush of ‘Christopher Tracy’s Parade’ is breathtaking: strings, trumpets, steel drums, a whole bestiary of strange vibrations swirling around in a quantum funk. A track like ‘I Wonder U’ is only 1'40" long, but seems to suggest whole new sonic horizons. Looking again at the photo of Prince on the front of Parade, I notice how much like a reflection it is: Narcissus before silvered water, examining his own features from every sylvan angle, fanning his delicate hands like branches to deflect or direct the light. Turn this mirror image around on the back cover and his eyes are suddenly shut, his top is coming off, black crucifix exposed. In the great, funny-peculiar and funny-ha-ha video for ‘Kiss’, Prince poses as the sex object while a seated Wendy (of the Revolution) steers the song. Fully clothed, amused, powerfully sexy in her own discreet way, Wendy wears the pants, raising a sceptical eyebrow at one point, while a half-naked Prince carries the fantasy. (And who is the strange, veiled, no-gender or bi-gender figure dancing behind them?)

Sign o’ the Times was Prince’s attempt to paste together a scrapbook from the wildly various excess of songs that had collected over the previous few years. A devil’s advocate critique of this ‘iconic’ record – routinely described as his best work and/or the best album of the 1980s, even as one of the best albums of all time – might start with the fact that, in retrospect, it doesn’t really hang together very well. Some of it is insanely good, but the mood is all over the place, and the sequencing is a mess. The dark cloud of the title track fades into the zippy, bubble-headed ‘Play in the Sunshine’, like a cheerfully inane TV announcer who cuts into the final minutes of Apocalypse Now with a Wacky Races cartoon. I can’t be the only Prince fan whose ideal reordering of Sign o’ the Times would start with the title track and end with ‘The Cross’: from apocalypse to revelation. Instead, after the stark, theologically minded ‘The Cross’, for no good reason we leap into the so-so live track ‘It’s Gonna Be a Beautiful Night’. But a lot can be forgiven for the sake of the astonishing ‘If I Was Your Girlfriend’, in which Prince manipulates his voice into a creamy, anti-macho croon, not a definitively ‘male’ or ‘female’ voice but something beguilingly in between: a carnal angel.4

Here we run up against a problem. At this point, Prince decided things had gotten too fancy, too playful, too … white. He needed to get back to his ‘real’ – which is to say his black – audience. Under this self-imposed fiat, he recorded something called the Black Album. He then withdrew it a week before it was scheduled for release, claiming it was in some way jinxed or haunted or evil, or something. The more prosaic truth may be that he suddenly realised how shockingly dull and pro-forma it sounded in comparison to his best work. All we really know is that sometime in 1987 Prince either finally fell apart, exhausted, or had some kind of semi-psychotic break, abetted by drugs he wasn’t used to, or by breaking up with Susannah Melvoin, or by burrowing too far into a self-created mythology of Good Prince v. Bad Prince.

Yet what ultimately emerged from this mysterious episode was one of his most fascinating song suites, and his last great work. Lovesexy (1988), improbable as it sounds, is Prince’s very own gospel album. On the sleeve he poses naked before God, as natural as the flowers that surround him. His lovesexy body looks lighter-skinned than earlier Princes, more like a Bollywood poster’s supranational kitsch. Around his head is a nimbus of purple petals, and a distinctly phallic pistil inclines towards his chest, where his hand spreads to hide a crucifix from our worldly gaze. The lyrics swing between gnostic-sex nuttiness and determinedly naive stuff that could have been written for an adult version of Sesame Street – and something else too, something far more unnerving, something like Prince’s showdown with his inner devil or Freudian death drive, which he called ‘Spooky Electric’.

If Dirty Mind was a hardcore celebration of the id, Lovesexy puts the ‘badness’ on trial. Here he’s debating the voices in his head: how dirty am I? Isn’t dirty good? And if not, why not? ‘I can learn to love,’ he pleads. ‘I mean the right way, the only way.’ Prince had made a career off his image as a steamy lover boy, yet here he is at this relatively late stage talking about a disabling hole in his life that can only be filled by ‘learning to love’. Some of the songs feel as if they’ve been worked on from the inside out, so that the weird subtext is up front. ‘Between white and black/night and day … No way to differentiate.’ The opening track, ‘Eye No’, seems on the face of it a big smiley hallelujah, but there’s already a chill in the air. At one point, apropos of nothing, he whispers: ‘The reason my voice is so clear/is there’s no smack in my brain’ – thus answering a question no one had asked. (Not that his voice is so very clear, as it happens.) The closing track is called ‘Positivity’, but the tone is distinctly edgy, downbeat, strung out: ‘Don’t kiss the beast, be superior at least … Hold on to your soul!’ Lovesexy suggests a whole other world of ‘spooky electric’ sound, a kind of disembodied soul music which, sadly, he was never to explore further.

In recovery from his electric shock, Prince became perhaps too determined to clear the murk from his work and life; it began to feel at times as if we were getting a Prince-bot, cognisant with all the outward signifiers of his art, but none of the hurt, or stealth, or oddness. He continued to write and record songs at an inhuman rate, but the heart was AWOL, the spark gone. On Diamonds and Pearls (1991), he was in slickly professional hit-making form, but a lot of fans were left feeling queasy. The one genuinely heart-stopping song on the album – the lovely, wistful ‘Money Don’t Matter 2 Night’ – is followed by the boilerplate funk of ‘Push’, which, bad as it is, isn’t nearly as bad as ‘Jughead’. There’s an emptiness here which the painfully amped-up production can’t disguise. Diamonds and Pearls is Prince-lite, assembled by a new cast of anonymous musicians, perfectly adequate professionals who would never surprise him (or us), and weren’t in any position, as the now exiled Revolution had been, to demand their part in a genuine collaboration.

The very thing that many of us thought was Prince’s greatest achievement – that he became one of the biggest mainstream stars of his day without hiding or diluting his blackness, producing instead something you couldn’t confidently call black or white – was now ditched in favour of songs with titles like ‘Pussy Control’: ‘I wanna hip y’all/2 the reason I’m known as the player of the year.’ His new ‘black’ vision had arrived, and it turned out to be a schoolboy caricature of shiny jewellery, fast cars and scantily clad models. Prince trying to act ‘gangsta’ felt not merely silly and self-defeating, but almost a form of betrayal. Who ever said we looked to him for something ‘real’ or ‘authentic’, anyway? (Plus: two dozen prison-tat-sporting young rappers could do that stuff better in their sleep.) Oddly, just at the time when he claimed to be returning to realer than real blackness, you’d swear he got two or three shades lighter for his publicity shots.

Prince claimed to hate revisiting his old songs, yet the music he now preferred to play was the stuff that seemed stuck in the past, while his music from the 1980s sounded more like the future than ever. On his website he was boasting of brave new technological innovations, but in his music he had retreated to a safe and homely funk. A song like ‘My Name Is Prince’, from 1992, is the sort of ego-bomb manifesto most artists drop early on, when they are still young enough that the arrogance can seem winning. A middle-aged man screaming that he’s the one and only doesn’t sound so sweet. On the contrary, such macho theatrics have a Trumpish effect: the more you insist on your uniqueness and invulnerability, the more it sounds like you’re struggling. By the end of the track, he is simply repeating ‘my name is Prince’ over and over, going on for so long you begin to worry for his sanity. Perhaps the trouble was all those muscly young rapper dudes at his heels: ‘My Name Is Prince’ makes more sense if we imagine Prince howling that boast at himself, geeing himself up in a world that’s changing fast.

Once, Prince had danced between identities; now he was clinging to the side of an icy mountain in a gale, using his brand-name as a crampon. Granted, ‘My Name Is Prince’ comes out of an old-school black tradition, a James Brown-style boast: ‘On the seventh day he made – me!’ But the tone is all wrong: there’s no self-mockery here; he sounds desperate. On the lamentable rap ‘Sexy MF’, there’s no actual emotion in his voice; it’s about as erotic as the cranked-up sound system in a tatty pole-dancing club – the tone is somewhere between resentful come-on and barely suppressed boredom. It’s as if he had issued a proclamation: from now on you will enjoy my music in just one way – black and therefore pro forma funky. The Prince who once afforded glimpses of so many impossible futures had retreated into an immovable tradition, making music that had only one origin, one destination, one reading – music like a recycled version of an old, old religion, no room left for fresh interpretation.

One evening recently I was in the local supermarket, which always has a surprisingly tasteful collection of old pop and soul hits on its playlist. ‘Raspberry Beret’ came on and I just couldn’t help it: I was instantly transported, singing along and showing out, right there in Aisle 3. It still sounded so good: those unexpected violins, the slightly ‘off’ backing vocals (a white girl sound, reversing the usual formula where a so-so white male lead is vamped by phenomenally good black female singers), the down-home cornbread of the song’s narrative queered by tiny splinters of subtext that black listeners would immediately flash on (Prince’s store-owning boss ‘didn’t like my kind/cuz I was way too leisurely …’). Was there really ever such a phantasmagorically odd pop hit as this, or was it all just a dream?

Following Prince’s death in April 2016, a lot of people went online to write about what he had meant to them, remembering how hot and otherworldly he was in his prime. Only you couldn’t help thinking that many of us were grieving for someone who was, if not long gone already, then in truth long absent from the centre of anyone’s thoughts. It had been an age since his music was everything it could be, and when our Prince radar did perk up in the 1990s and early 2000s it tended to be for extra-musical matters. He sacked the capable professionals who had secured his breakthrough in the 1980s and replaced them with friends and relatives, most of whom had no previous experience with the tasks he gave them. At one point, he sued some of his most adoring and resilient fans over matters of copyright relating to the fan sites they ran online. It was in 1994, when he was on the way to marrying Mayte Garcia and you might have expected him to be head-in-the-clouds happy, that he entered a business meeting with Warner Brothers executives with the word ‘SLAVE’ painted on the side of his face. And then there was the name change: from roughly 1993 to 2000 he was officially  ; in an interview he gave in 1999 he said he ‘wanted to move to a new plateau in my life and one of the ways I did this was to change my name. It sort of divorced me from the past and all the hang-ups that go with it.’ Perhaps a course of psychoanalysis would have been a better idea than an audience-confusing gimmick. (Some claimed that the name change was something Prince thought might free him – at a stroke – from his Warner Brothers contract.)In a song on Emancipation, from 1996,

; in an interview he gave in 1999 he said he ‘wanted to move to a new plateau in my life and one of the ways I did this was to change my name. It sort of divorced me from the past and all the hang-ups that go with it.’ Perhaps a course of psychoanalysis would have been a better idea than an audience-confusing gimmick. (Some claimed that the name change was something Prince thought might free him – at a stroke – from his Warner Brothers contract.)In a song on Emancipation, from 1996,  -Prince sings a song about plain old Prince-Prince, and declares him ‘dead like Elvis’. Most boys grow up with some kind of childish ambition to be king of this or that world, but what happens when a child is baptised Prince before he’s said or done a thing? Right from the start of his career, names and naming, signs and alphabets, seemed to matter deeply to Prince. But what is a name, when you get down to it? It isn’t something you can hold squarely in your hand like a lump of gold. It’s wholly immaterial. It can make you feel like a god before your time – but equally, maybe, a ghost in your own life.

-Prince sings a song about plain old Prince-Prince, and declares him ‘dead like Elvis’. Most boys grow up with some kind of childish ambition to be king of this or that world, but what happens when a child is baptised Prince before he’s said or done a thing? Right from the start of his career, names and naming, signs and alphabets, seemed to matter deeply to Prince. But what is a name, when you get down to it? It isn’t something you can hold squarely in your hand like a lump of gold. It’s wholly immaterial. It can make you feel like a god before your time – but equally, maybe, a ghost in your own life.

Paisley Park was an imaginary space first – a microcosmic Eden, over the hills but very close by, where everyone was welcome: the halt, the lame, the uncool, the dorky, anyone whose beauty or sexuality didn’t fit inside square society’s miserly norms – before it became the name of Prince’s Minneapolis-based complex, built with the profits from Purple Rain, comprising two recording studios, a dance studio and a huge soundstage, where videos were filmed and performances rehearsed. It also contained his home and offices. It was a smart move, no doubt, to set up his own studio, but you have to wonder whether it’s a good idea for anyone to bring everything they need in the world together in one place. It’s a kind of Boy’s Own dream, which brings with it the dangers of insularity, a creeping alienation from the currents of life elsewhere. Prince had sealed himself off inside a hygienic smiley-face concept-world (the initials of Paisley Park might also stand for Pleasure Principle). But the original happy family dream of Paisley-Park-the-concept was eventually replaced by a vision of pleasure that felt more like a 24/7 duty, even a bit of a slog. Prince constructed a world in which absolutely nothing was left to chance; in which everything he saw, all around him, every hour of every day, was a reflection of no one and nothing but Prince.

One of Mayte Garcia’s frothier insights in The Most Beautiful: My Life with Prince concerns someone known in Paisley circles as the ‘foo foo master’. Whenever Prince toured, every hotel room he stayed in would be completely made over by this employee to exact, and exacting, Princely specifications: posh candles, fluffy rugs, general New Age … foof. (Prince even got into the habit of demanding a white baby grand piano at every hotel stop, until saner organisational minds prevailed.) Look in this mirror, children: each and every space is simultaneously fantastical, but also an endless repetition of the Same. Nothing ever changes in Prince world. Maybe on some level this was actually his ultimate fantasy? As if he had been given a benevolent genie’s wish and his answer was: ‘O please let me have the exact same dream every single night!’ Everywhere is home, nowhere is home.

By the time of sets like 3121 (2006) we’re a long way from the original communal all-join-in vibe of Paisley Park: we’re back on the outside of the superstar life again, looking jealously in, our noses pressed against the glass of Prince’s ultra-tasteful pad, his non-stop party, his supercool Hollywood pals. What was once the dream of a happier community (sometimes black, sometimes an alchemical merger of all our colours) is now the same old story: I got mine, brother, screw you. Some fans insist 3121 is a high-minded biblical allegory, but I’m not buying it. (We put up with this kind of thing from Prince for decades: every time he came out with a new spiritual paradigm he shifted the goalposts, changed the rap, gave out a new party line which was short on convincing detail but long on wishy-washy utopian shine.) The combination of Elle Decoration-style shots of his Los Angeles rental and a front-of-sleeve image of him, face to the wall with the titular number painted on his back, makes him look as if he’s his own jailer in a luxury house arrest. The Paisley Park pleasure principle (‘The smile on their faces/speaks of profound inner peace’) has become a three-line whip promoting 24/7 hedonism. Prince is playing house: music by Prince, décor by Prince, health food snacks chosen by Prince. (He even installed a swear jar.) There isn’t a moment in the day, and not a detail anywhere (scent, serviette ring, artisanal stationery), in which he doesn’t have the final say. Here is a small, deflating glimpse of what it may have been like being married to Prince: absolutely everything, including even your own pleasure, is conceived, conducted and monitored according to His royal tenets.

The way in which every purple detail (no matter how small) is interlinked with every other, from top to bottom, in his unique control-freakish way: perhaps it was no surprise that things did start to go wrong, all at the same time. You wonder whether his eventual conscription as a Jehovah’s Witness was responsible for certain changes in his persona and personality, or whether he chose that faith because it was such a serendipitous fit with the way he already felt about a fast-changing world, and how best to secure his own place in it.

Garcia’s book is the nearest thing we have to a believable portrait of Prince in downtime. Even here, he glows distantly like a quasar; it’s hard to make out the lineaments of a true inner life. There is a hummingbird effect: he keeps so busy you can’t see through the blur to make any sense of why he behaves in the ways he does, or makes the decisions he does. A workaholic who writes endless songs about how much he just hangs out. A perfectionist who releases way too much sub-standard work. Garcia catalogues his habits, tics and obsessions, most of which seem to boil down to a creeping fanaticism about image and control. He began to make over everything in the vicinity (including his wife) according to his own vision: ‘Prince’s house was repainted a different colour on a regular basis and a new car … was custom-painted to match it.’ After a year or two everything would be scrapped and ‘his whole life … would undergo a change of wardrobe.’ Not surprisingly, it never really feels like we get past this image armour to any sense of Prince as a fully human presence, and the reason seems to be that Garcia never did either. ‘As his wife, I could get closer than a girlfriend but … there was a point of Do Not Enter.’

As with Madonna, there’s the feeling that no marriage could ever compete with a star’s restless, near inhuman will-to-conquer. Garcia doesn’t use the book to get her own back – she may even be underplaying her late husband’s more infuriating behaviour – but nonetheless she reveals more about Prince than many fans will want to know, not least about his courtship of her when she was still 16. They initially met at a show in Mannheim in August 1990, when Prince was touring Europe and Garcia – with the blessing of her parents – sent him a VHS tape of her belly-dancing. According to her, their relationship remained entirely proper in these early years, during which she edged closer to the heart of the Purple world, first as a kind of junior muse (during the rest of his 1990 Nude tour ‘he continued to call me several times a week. We rarely spent less than two or three hours on the phone’), then as a New Power Generation-era dancer for his live shows. In 1993 they became lovers, and three years later they were married. Strictly no carnal border crossings until she was of legal age, she insists. Still, it’s a fine line. Prince, she says, ‘never denied the occasional impure thought crossed his mind, but the truth is, he was too wise and decent to take advantage of a 16-year-old’. By the end of My Life with Prince you may think that rather than being ‘too … decent to take advantage’, he might have been sleazily wise enough to know that not taking advantage too soon was all part of a successful long-term grooming campaign. (I recall the strange voice, distorted and slowed to a devilish basso profundo, that opens 1999: ‘Don’t worry – I won’t hurt you – I only want you to have some fun.’)

In general, Prince only had eyes for (much) younger women. ‘I think his preference was more than physical,’ Garcia writes. ‘It was about the power balance. He didn’t like to be argued with.’ She quotes some of his love letters, written in his trademark semi-hieroglyphic number-pun alphabet. Again, it feels a tiny bit off, coming from a near middle-aged roué: ‘EYE’m glad U’re young cuz U can wait 4 me.’ Is this what it means to be a beautiful dreamer? Did he write this way to all the money men and lawyers, too? And what about the memoir he was working on before his death, The Beautiful Ones, which is finally due to come out late this year: will it be set in Prince-text?

Once they are married, Prince throws a huge strop when Garcia’s father takes a happy snap of the happy couple. NOT ALLOWED, NO EXCEPTIONS: there are to be no unrehearsed photos anywhere in Paisley Park without prior arrangement. Black showbiz maintains a tradition not unlike that of European royalty, in which you always present yourself to your public in character and at your very best. As with his heroes James Brown and Miles Davis, it’s hard to picture Prince outside a certain rigorously maintained ‘look’. But in Garcia’s anecdote Prince’s touchiness about image feels less like showbiz corn and something closer to undiagnosed pathology. You have the impression of someone who rarely, if ever, came out of character: there is no other side to this mirror. Showbiz habits are a convenient excuse when someone demands more of the real you than you are prepared to give.

The most revealing part of Garcia’s book concerns the birth and, six days later, the death of the child she calls Amiir (sometimes referred to elsewhere as Boy Gregory). He was born in 1996 with Pfeiffer syndrome type 2, a rare genetic defect that causes the foetus’s cranial bones to fuse, resulting in severe skeletal and systemic abnormalities. Garcia’s account of her husband’s bizarre behaviour in the aftermath of the child’s death is chilling. Maybe he retreated into a murky inner space because he was suffering in a way he had never learned to express, or because he understood himself well enough to know that he had a void where such feeling should be. But it’s more likely that in the absence of the usual human reflexes, he had installed an alternative set of wholly superficial showbiz habits, all emotion conceived in terms of what is or isn’t made available for public consumption. Did he think it unmanly to be seen as in any way vulnerable? Did he find it impossible to unbuckle the rigid armour of his persona and admit that his rosy-fleshed mythos, equal parts happy carnality and religious utopianism, could end like this: with an ‘imperfect’ child, with medical disaster, death and grief?

Rather than cancel a scheduled appearance on Oprah, Prince seems to have entered a fugue state. He could surely have withdrawn, or maybe done the show alone, without Garcia. Instead he practically forced her, still unwell, still devastated, to stand in the glare of the TV lights and pretend everything was lovely in their marital garden. It seems cruel, oblivious, or demented. In answer to Oprah’s gentle questioning about the child, Prince rolled out some pseudo-religious gobbledegook signifying that everything was absolutely right and joyful and as it should be, according to God’s will. ‘It’s all good, never mind what you hear.’

Soon afterwards, Prince decided to go ahead with the promo for a new single (‘Betcha by Golly Wow’), and said he wanted the video to feature a sweetly ambiguous storyline mirroring the pregnancy, full of smiling children and twirling dancers and Mayte herself ‘sitting on an exam-room gurney in [her] hospital gown’. Unbelievably, Prince asked her to do these scenes in the same room, in the same hospital, she had only just left behind. Throughout the pregnancy, Garcia and Prince had argued about her medical treatment. As the wife of a multimillionaire celebrity, she expected the best obstetric care money could buy. Prince insisted that such diabolical science went against God’s will, and that as a mere wife she should unthinkingly go along with her husband’s every command. Even when it became clear something wasn’t right, Prince held fast. ‘If there’s something wrong,’ he told Garcia and the obstetrician, ‘it’s God’s will. Not because we didn’t prepare.’ Later, after the birth, when the obstetrician told him that Garcia needed to be checked back into hospital to allay the risk of permanent infertility, his immediate response, without consulting his wife, was: ‘No. God’s hand is on her. She’ll be fine.’ As Garcia struggled to deal with a ‘grief as airless and dark as the bottom of the ocean,’ Prince told her, ‘I can’t be here, I have to go,’ and ‘went to play a few gigs and promote the Emancipation album’.

Where did Prince’s grief go? In the years following the loss of Amiir he released some of his all-time weakest work, on albums like The Vault: Old Friends 4 Sale and Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic. After his divorce from Garcia, in 2000, Prince got married again, on New Year’s Eve 2001, to Manuela Testolini; she was 18 years younger than him and it appears he had begun seeing her while still married to Garcia. His second marriage lasted five years and there were no children.

Before April 2016, Prince wouldn’t have been on anyone’s list of showbiz people most likely to die of a drug overdose. We now know there had been problems for far longer than anyone suspected or wanted to admit. Garcia says there were ‘several occasions when he told me he was “sick” or that he had a “migraine”. Looking back I can see that it was something else.’ In 1996, shortly after they lost their child, she surprised him on the Emancipation tour and ‘found wine spilled on the rug in the hallway and vomit on the bathroom floor’. The Vicodin she had been prescribed for post-birth complications ‘kept disappearing. The prescription would be filled, and a few days later, most of the pills would be gone. I assumed he was hiding them to keep me from hurting myself.’ Prince evidently did a good job of bamboozling everyone around him; keeping the smiley mask polished bright had been second nature for a very long time. His studio ‘vault’ contained so many spare songs he could probably have continued for years without having to write anything new. When a song from 2006 boasts that his hot new funk is so on-trend it’s coming down ‘like the wall of Berlin, y’all!’, you really have to wonder.

People can have an on-again off-again relationship with their drug of choice for years before fetching up with a full-blown addiction. Prince seems to have compressed this untidy, protracted arc – just as James Brown did – by leaping overnight from disciplined abstinence to shivery chemical bondage. Never mind the occasional cheeky puff on a joint or weekend Ecstasy tumble: he goes straight to super-strength prescription narcotics. The official version is that it all began with operations Prince underwent on his poor shattered hips, frail after decades of on-stage athletics in unsuitable high heels. An official investigation after his death by the authorities in Minneapolis revealed a situation way beyond any kind of measured therapeutics or sensible daily regimen: he was hip-deep in the sort of drugs normally administered only for extreme pain – the slivered no-self of atrocity survivors, or late-stage cancer patients. Garcia reports one of his long-time road crew confessing to her: ‘Everything was great until Purple Rain. Then he got everything he ever wanted, and he didn’t like it.’ All that left-over time to fill! (Writing in the NME, in 1985 or thereabouts, I – approvingly, at the time – described Prince and Michael Jackson as figures who had ‘died into music’.)

Prince’s most affecting love song is a kind of phantom love letter, addressed to some lost or jettisoned part of himself. He never again produced anything remotely similar to ‘Sometimes It Snows in April’, the closing track on Parade: an otherworldly chiaroscuro of liquid acoustic guitar, piano caress and semi-wordless vocalese. Some of the lines are awkwardly sung-spoken, as if they had just popped into his head and he is squeezing them into the rhyme scheme, starting impossibly high then falling into a near mumble, speeding up, slowing down, words on the edge of a meaning so personal it’s hard to parse. One moment the singer is crying (‘I used to cry for Tracy because he was my only friend …’), the next he is claiming that ‘no one could cry the way my Tracy cried,’ as if the singer himself were Tracy.

Maybe I’m just slow, or was hypnotised by the song’s glacial beauty, but it was years before I realised what was going on in this dark and wistful snowsong, with its doubling, mirror-on-mirror affect. In the film Under the Cherry Moon (1986), for which Parade is putatively the soundtrack, the character fated to die, Christopher Tracy, is played by … Prince. So, in effect, he’s singing as someone else, and mourning his own introjected death. ‘April’ is Prince’s love song to the split inside himself: the blithe, gigolo part has to die, in order to reclaim the traces of some other ‘I’ long starved of attention. The song stops suddenly, unexpectedly: a tiny parallel death. Turn the record over, back to the beginning, and we are back to the rush and bustle of ‘Christopher Tracy’s Parade’, in which the titular Christ/opher is raised again, reborn.

It’s the one Prince song that might fit comfortably in the catalogue of his long-term muse, Joni Mitchell. You can easily imagine mid-1970s Joni using the line ‘a long-fought civil war’ to describe some wounding amour. On 16 April 2016, five days before his death, Prince stopped off at a local record store and bought new copies of Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book (1972) and Mitchell’s Hejira (1976). Here was a past he felt comfortable with, also perhaps a clue to his ideal self: something halfway between funk-soul brotherhood and a pale, distant siren. Hejira: like Parade, another black and white sleeve, another blank-faced self-portrait. Icy light, dim faraway shadows, a black crow flying in a blue sky. Open up the gatefold and there is Joni, like Prince and his mirror, viewed from behind and turning away: a dark-feathered bird of ill omen.

Just before his death, Prince was playing all the old songs again: just himself, a piano and a microphone5 Playing the songs his fans wanted to hear, with appropriate lightness or gravity. People I know who saw these shows said they were something else: piercing, alive, unforgettable. And while it may not have been a meaningful solution to his long-term creative problems, maybe revisiting the emotions buried in those songs helped jog loose something inside. A breath of genuine memory, thoughts suitable for the age he was and not the silly, death-denying pretence of his Everywhere All the Time Party. Think of something like Mitchell’s collection Both Sides Now (2000): a mixture of torch songs, old standards, new takes on such early classics as the title song and ‘A Case of You’. She returns to these songs of her (and our) youth and sings them inside out, sings them with her 57-year-old voice and all it contains: all the love, desire, and disappointment; all the changes, choruses and chords; all the lessons learned from long hours working with brushes and paint. Cigarette smoke, lipstick and holy wine. A late Rembrandt self-portrait in song – and it’s absolutely sublime.

Prince died alone, of course, in the middle of the night, between floors at Paisley Park, a heartbeat away from his studio. The middle of the night, when names and colours matter least. In the end, a painful reality triumphed over all easeful fantasy, and pain-numbing drugs emptied out the interfering dialogue of everyone and everything else. One morning you wake and all the time has melted away: no more hotel bedroom afternoons, light moving like seaweed over the pale impersonal walls. All your life, dreaming of the other side of the mirror, where the colours all reverse, and now you finally remember what it was you saw there, so long ago: clouds, full of rain.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.