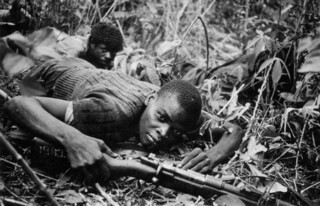

Don McCullin’s retrospective at Tate Britain (until 6 May) is proof that it pays for a photojournalist covering victims of conflict and hardship to get up close: not quite eyeball to eyeball, but near enough to suggest a portrait. Most of McCullin’s photographs ask us to look frankly at the human face, and often our gaze is reciprocated. Even a dead soldier with the North Vietnamese Army, killed during the Battle of Hue in 1968, seems to want to get us into focus through his half-closed eyes. (This was the only war composition that McCullin ‘contrived’, he explains, by scattering the man’s possessions on the ground beside him: souvenir snaps of his family, a few folded pages of what might be a letter and a drawstring bag full of bullets.) When we can’t tell from their expressions how people are experiencing calamity or danger, it’s because McCullin has been drawn away for good reasons from the human face, to groups of people who haven’t seen us: down-and-outs with their backs to a fire or Phalange gunmen on their knees beneath a chandelier in the wreckage of the Beirut Holiday Inn. Or, sometimes, to one of his definitive landscapes with smoke: coal-fired steel plants in Durham in the early 1960s; a tank shell exploding in Iraq thirty years later. But the faces are what we remember, and the more we encounter, the less we’re able to mark our distance from McCullin’s subjects. They look as if they’re within arm’s reach: if they whispered a greeting or a curse, we would hear it clearly. And as we move around the exhibition, from one room to the next, face after face, a serial crowd begins to gather, pressing forward from conflicts in distinct parts of the world, and – despite the carefully historicised curating – assembling in the present.

If McCullin’s remarks about his work are reliable, this was his intention all along, from his early stint as a photojournalist in Cyprus (1964), through the Congo Crisis (1964), the ‘Indian famine’ in Bihar (1967), Biafra and Vietnam (1968), Cambodia (1970), Northern Ireland (1970), East Pakistan, shortly to become Bangladesh (1971), the Karantina massacre of Palestinians, Kurds and others during the civil war in Lebanon (1975), Ronald Reagan’s war in El Salvador and the massacre of Palestinians in Sabra and Shatila (Lebanon, 1982), to the retreat of Iraqi Kurds after the Gulf War (1991).

McCullin often returned to the sites of earlier tours of duty, driven both by news agendas and his wish to follow events, in Cyprus, Biafra, Vietnam, Cambodia (as the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh in 1975) and Lebanon, where the civil war dragged on. These assignments were punctuated by visits to poorer parts of Britain: in the north, Bradford, Liverpool, Doncaster, West Hartlepool, Sunderland; in London’s East End, Liverpool Street, Whitechapel, Aldgate, Spitalfields, where he photographed the homeless. (McCullin took the photographs and worked on the enlargements that Antonioni used in Blow-Up, but he couldn’t be less like Thomas, the photographer whom we first encounter leaving a London doss house where he’s spent the night taking pictures for an art book.)

McCullin had started out as a freelancer with the Observer before he signed up with the Sunday Times Magazine in the 1960s. But he was troubled by Murdoch’s acquisition of the paper in 1981, and went his own way a couple of years later, after a row with the incoming editor, Andrew Neil. After the Gulf War (1990-91), he spent much longer periods away from conflict zones. He travelled to religious festivals in India and photographed the landscape around his home in Somerset, going on to get occasional assignments from NGOs: the Aids crisis in southern Africa for Christian Aid at the end of the 1990s; Darfuri refugees in Chad for Oxfam in 2007. There was also a longer project of his own in the works. Southern Frontiers – monumental, pensive studies of Roman imperial ruins – took him among other places to Palmyra before the war in Syria. After Islamic State trashed the site in 2015, he returned, but the Russians wouldn’t let him record the devastation. Several of his Southern Frontiers photographs are on show at Tate Britain, along with his domestic landscapes – mostly Somerset – and a couple of still lifes.

‘After photographing wars and revolutions for two decades,’ McCullin wrote at the end of the 1980s, ‘the memories of those painful years nearly always try to spoil my days, even now, here in England.’ Earlier, reflecting on his hikes in Yorkshire and Hertfordshire after he left News International, he noted the way ‘the wind rushes through the grass and I feel as if I’m on the An Loc road in Vietnam’ – the battle of An Loc took place in 1972 – ‘hearing the moans of soldiers beside it. I imagine I can hear the 106mm howitzers in the distance.’ Statements of this kind, drawn from McCullin’s writings and interviews, can be found alongside his photographs in the gallery and the catalogue, suggesting a sacrificial process, in which the reporter has transacted his peace of mind – even his mental health – for the right to show ‘unbearable’ truths (the adjective crops up more than once in the catalogue essays). Then there were the physical risks. In Cambodia in 1970 he was severely wounded by mortar fire, injected with morphine and dumped on a truck with other casualties from the same shell. Lurching about on the tailboard, he kept taking photographs, including one at Tate Britain of a dying Cambodian government soldier. In El Salvador in 1982, McCullin was on top of a house during a firefight when the roof collapsed. He fell with it, breaking an arm and a rib, and lay for 13 hours ‘pinned down as the battle raged’.

McCullin has taken what he’s seen and photographed very personally: ‘I have never been able to switch off my feeling,’ he wrote in Unreasonable Behaviour, his 2002 autobiography, ‘nor do I think it would be right to do so.’ He readily admits that he has been scarred by his experiences and thinks of his indisposition as part of his vocation: ‘seeing, looking at what others cannot bear to see, is what my life is all about.’ And, in a Guardian interview in 2010: ‘You have to bear witness. You cannot just look away.’ In other words, a photographer must never flinch; there is no shot that a sense of propriety or respect could rule out. It was probably the right approach, not just for McCullin and his editors, but for posterity. Even so it raises difficult questions.

One to dispense with immediately is whether spectators become ‘inured’ to the brutal quality of McCullin’s images. The answer is no. The photographs remain as disturbing as they were when they were first published, in the midst of a new and violent American imperialism and the aftershocks of unfinished decolonisation (these two forces can often be seen intersecting, as in his photographs of Congo, Vietnam and Cambodia). A more troubling issue is whether a photographer should refrain from shooting a scene on the grounds that it is too terrible, or too intrusive. Part of McCullin’s answer is that even though the dead can’t consent, his living subjects could and did. He often worked at such close quarters that consent was a precondition of the photograph, most famously in his record of the murders of Turkish villagers in Cyprus in 1964. ‘I was met with the warm blood of two men in front of me,’ he recalled in Shaped by War. ‘Suddenly a group of distraught people came in … I was really looking for their blessing to continue … I started quietly taking photographs.’ McCullin worked with great sensitivity but he never looked a gift horse in the mouth.

Reflecting on her coverage of Central America during the early 1980s, Susan Meiselas remembered thinking that her photographs of Somoza’s overthrow by the Sandinistas would serve as ‘the link to understanding why the people of Nicaragua were so outraged’. That link, of course, was to the US public, which had voted Reagan in and Carter out by a comfortable margin in 1980. Four or five years later Meiselas concluded that the public ‘could not relate their reality to this image. They simply could not account for what they saw.’ McCullin’s problem was different: the public, politicians, even delegates at the UN might be moved by his photographs, but very little seemed to budge. Slowly, too, the tide was turning against the kind of work he was doing, in part because his own public was quickly learning to become distracted.

When Harold Evans ran the Sunday Times, from the late 1960s until 1981, British readers on the left and right could still assent to the paper’s international news coverage in the hope of a future without the damage and misery that McCullin’s images of proxy wars between the free world and the communist regimes brought to them in the colour supplement. Circulation with Evans at the helm – and McCullin still on board – peaked at 1.4 million in 1980. It took many years for Murdoch’s lieutenants to surpass that figure, but along the way they recast their ideal reader as an attention-deficit consumer, eager for bulk browsing, including supplements such as the Funday Times, originally for adults as well as children, and the annual Sunday Times Rich List, for adults who should know better.

By the time the Sunday Times got back up to 1.4 million readers in the late 1990s, McCullin was in his sixties, still troubled and given to bouts of memorial introspection. Where a photographer like Meiselas might simply have gone on to broaden the field – among other projects, she edited a book of work by Chilean photographers who had lived through the Pinochet years – McCullin became more selective, pursuing personal projects and a few commissions. He returned to the darkroom, where he began to re-examine his foreign archive, bringing his remarkable skill as a printer to bear on images whose quality was scarcely apparent when they first appeared in newspapers. Fear, grief, pain, outrage, death with dishonour – the sweep of war, hunger and poverty from Cyprus to Iraq – were coaxed into a lavish, even sublime, register. All the gelatin silver prints on show at Tate Britain are McCullin’s own, and they are astonishing to look at, though the virtuosity of the images and the distress they record are at times impossible to reconcile.

Will there be another big McCullin retrospective? Arguments about the asymmetrical flow of information across the North-South divide, the ‘decolonisation’ of news, and the way the Western media reported events unfolding in poorer countries, were raised in earnest in 1980 with the publication of the MacBride Report, Many Voices, One World, under the auspices of Unesco. Its promise of a ‘new, more just and more efficient world information and communication order’, championed by the Non-Aligned Movement, never came to much: anxieties about who got to tell what stories – often painful stories – only became sharper. By the 2000s it was an open question whether a European could claim to make accurate representations of African countries in the first place. That was the message of ‘How to Write about Africa’, Binyavanga Wainaina’s scathing satirical piece in Granta in 2006 (‘always include The Starving African, who wanders the refugee camp nearly naked, and waits for the benevolence of the West’).

McCullin worked mainly in places where British colonialism had left its mark or where Britain lent uncritical support to Washington. In Nigeria, the British were both the former colonial power and the willing arms supplier for the government in Lagos, as it fought and starved the Biafran secessionist movement into defeat. McCullin had a right, arguably a duty, to cover these conflicts for the British public. Fifty years on, if we recoil from his harshest images – among them a famous shot of an albino famine victim in Biafra in 1968 – it’s because we can no longer look misery in the face without wondering where we stand in relation to it and what the subjects of such iconic photographs would have said if they’d been the keepers of the record. This is true, especially, of images from African states in adversity, served up to European audiences who worry how to commiserate. It is easier to look with a clear eye at the pain and indignity that McCullin catches in his photographs of class war on the home front. The injustices of postwar Britain were just as much a part of McCullin’s bitter argument with the world as the scenes he recorded on his foreign tours.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.