At the furthest edges of the known world, medieval travellers encountered creatures who held a single giant foot over their head as a makeshift parasol and fearsome hybrids with eyes peering out from their chests or set in the middle of their foreheads: they were classed as wonders, close kin to the monsters and dragons of classical genealogies. When Thomas Browne was considering the dietary prohibitions in the Bible, he was puzzled that griffins were listed, commenting that griffins were ‘Poetical Animals, and things of no existence’. The combination of eagle and lion was, he wrote, ‘monstrous’ and couldn’t possibly exist in reality, although he conceded that some flying creatures ‘of mixed and participating natures, that is, between bird and quadruped’ – he cites bats as an example – are ‘a commixtion of both, rather than an adaptation or cement of prominent parts unto each other’.

In these fantastic inventions, wings are surely the most popular element of all. From the earliest surviving sculptures of Babylon and Assyria, wings have been borrowed from actual flying creatures – insects as well as bats and birds – to lift a huge cast of guardian monsters and imaginary creatures (‘Poetical Animals’). Heavenly beings are primed to ascend, while devils plummet down like Lucifer or, like Milton’s Satan, plane over Pandemonium. In Dante’s Inferno the serpentine Gerione, a monster with the counterfeit face of a beautiful man and a sting in his scorpion tail, carries Dante and Virgil down to hell on his back. Gustave Doré gave him the wings of a giant bat. Caravaggio borrowed eagle’s wings from Orazio Gentileschi for his figure of Eros: they seem to have been a most covetable studio prop. Fuseli studied moths and butterflies to realise Titania’s fairy attendants accurately and Victorian artists such as John Anster Fitzgerald also borrowed features from the insect world to make their fairylands convincing. Today, through the ingenuities of CGI, many of these hybrids now speak and weep, appearing convincingly embodied and entirely sentient. Entertainments, from story books to ‘augmented’ virtual reality and advertising images, routinely show us secondary worlds, naturalising a host of mythic figments (sphinxes, Gallivespians, mermaids, unicorns).

Serinity Young works at the American Museum of Natural History and is a specialist in Tibetan art and artefacts; an earlier book, Courtesans and Tantric Consorts: Sexualities in Buddhist Narrative, Iconography and Ritual, was also concerned with power and pleasure. Her method is encyclopedic, not unlike J.G. Frazer’s in The Golden Bough, and in Women Who Fly she has marshalled a wonderful gallery of flyers – a kind of panangelium – from cultures far and wide. Whereas Clive Hart’s Images of Flight (1988) didn’t distinguish its subjects by gender, Young focuses on female figures. Hers is a festive anthology, arranged in two main categories – Supernatural Women and Human Women – which teem with divine and prodigious heroines: angels and demonesses, witches and mystics. Young admires the Valkyries, in their winged helmets, who ride the clouds, and writes eloquently of the djinn from the Thousand and One Nights, who, like swan maidens, hide away their cloaks of feathers in order to live on earth. The rich and eclectic spread of material, however, opens up more questions than it can answer. How has this imagining of the winged female impinged on real women? Where do these symbolic creatures interact with reality? What is the status of a Valkyrie or a fairy now?

The book’s title deliberately plays with our sense of proper categories. Would you call Homer’s Ino, the nymph of the lovely ankles who rises from the sea to help Odysseus, a ‘woman who flies’? What about the Wilis in Giselle or Tinkerbell in Peter Pan? The status of ‘women’ for these ethereal beings feels a bit of a stretch: their ease of flight marks them out as not suffering the same physical limitations as humans. Young sees flight as a fantasy of female liberation: ‘Women who fly want to be somewhere else to stay there; they do not want to return to conventional experience, which they view as captivity. They require us to rethink our ideas about female waywardness.’ Her book sets out to shake conventional prejudices against flightiness, on behalf of ‘enraged, courageous’ sisters who let fly like ‘aerial warrior women’.

Monsters are often female – the sphinx, the sirens, Scylla and Charybdis, the night-mare and the night-hag – but wings can have the effect of cancelling gender, as in the case of angels, who, despite their masculine names (Gabriel, Raphael), are usually depicted as androgynous – or unsexed. Their wings represent an escape from the drag of flesh and time, from mortality and the need for reproduction. Words for ‘spirit’ derive from airy imagery – vapour, breath, wind, even gas – and from birds: the Egyptian hieroglyph for the soul after death (Ba) is a bird, and in a famous scene from the Book of the Dead the heart of the deceased is shown being weighed against a feather, representing Maat, the goddess of justice. The Holy Ghost in the form of a dove speeds down shafts of light to enter Mary through her ear, impregnating her with a spirit-word (Buck Mulligan in Ulysses refers to ‘the gaseous vertebrate’). In Islamic tradition, Solomon has power over the winds and can travel through the air. Ariel is able ‘to fly,/To swim, to dive into the fire to ride/On the curl’d clouds’. Prospero calls him his ‘chick’, his ‘airy spirit’; Ariel doesn’t need wings but can speed through the air of his own volition or ‘ride on the bat’s back’ to do his master’s bidding. Imaginary beings who share in this ethereal lightness remain physically unchanged: there’s no such thing as a wrinkly archangel. The goddess Nike who, as the Winged Victory of Samothrace, appears so thrillingly poised at the top of a flight of stairs in the Louvre, was the inspiration for Young’s project; the sculpture, she writes, ‘surging with power up and through her arched and extended wings, froze me in space’. Nike’s triumph is not only over an enemy but over the laws of the body, the pull of gravity, the march of time (though time has taken its toll on the sculpture’s head and arms). Christian angels were modelled on these classical totems, and their beautiful, often rainbow-feathered wings annex the imagery of another classical figure of speed and light, Iris, the rainbow messenger of the gods.

The erotic connotations of flying saturate metaphors of thrills, rapture and ecstasy across a range of languages. Lucky charms in the shape of winged phalluses and winged vulvae have existed since classical times, but more surprisingly have been found in medieval shrines in the form of pilgrims’ badges. Pop songs return to the imagery over and over again. Erica Jong’s zipless fuck in her famous novel is a dream of flying – without fear. Freud noted that dreaming of levitation was associated with the pleasure impulse and connected it to the literal, physical rise of the penis – the fear of flying is ultimately a fear of collapse, of failing and falling.

The erotic charge doesn’t weaken in the experiences of saints and visionaries. Teresa of Avila complained about her tendency to rise into the air while praying (the other nuns had to hold her down). Christina Saint-Trond (c.1150-1224) became known as ‘the Astonishing’ after she rose from her coffin as the requiem mass was being said for her soul and, ‘like a bird, immediately ascended to the rafters of the church’. Her Vita by Thomas of Cantimpré reports the evidence of many ‘straightforward witnesses’ and recounts her numerous feats – she lived ‘in trees in the manner of birds’, walked on water and performed other holy austerities, some of them bizarre and repellent. Young writes that Christina, having died once, ‘was using her body to demonstrate her interstitial state … combining shamanic behaviour and sympathetic magic, whereby enacting one’s desire – in this case, literally climbing towards heaven – can lead to its accomplishment – that is, arriving in heaven’. But she doesn’t consider the meaning of these episodes for the community that believed in Christina’s flights and was asked to believe in her as a saint after her death at the age of 74, very old for a woman of her time, any more than she tackles the Catholic dogma of the Assumption of the Virgin, which holds that Mary rose in her body to heaven, the only woman there present in the flesh.

The instances of Mary and Christina point to a difference between winged beings and goddesses, saints and others who can fly under their own energy. Aphrodite hurls herself into battle at Troy to bring out her son Aeneas, but she doesn’t appear to have wings nor does she change her shape into a sea eagle, as Athena does at the beginning of the Odyssey. The princess in a Chinese fairy tale who was banished to the moon has no need of wings, though in images of her ascent her ribbons, sleeves and draperies curl and flutter around her buoyantly, ‘like feathered clouds’. The richest and most unexpected sections of Women Who Fly look at bodhisattvas and esoteric dakinis, who float down to earth and can transform themselves and transfigure the lives of those they touch. It does seem especially marvellous to take flight without need of wings, as happens in dreams (though in mine I usually have to pedal away furiously). Wonder Woman, like Superman, speeds through the air as if rocket-fired. The Darling children in Peter Pan have some trouble at first: ‘they could not help kicking a little, but their heads were bobbing against the ceiling, and there is almost nothing so delicious as that.’

Alongside visions of fairy freedom and divine gravity-free lightness, practical approaches to flight began surprisingly early. Alexander the Great, according to classical legend, harnessed griffins to a basket and baited them with a carcass hung just out of reach so they would keep flying towards it and carry him ever onwards and upwards; when he saw the earth from that high vantage, he despaired that there was so much more of it to conquer. Leonardo’s experiments in flight are famous, though he wasn’t the first – perhaps that honour goes to Daedalus. Deus ex machina designs for the stage created illusions of ascent and descent to depict Medea’s last exit, or the hero Bellerophon’s adventures on Pegasus, with pulleys and hoists hidden behind painted clouds. Novelists and travellers proposed exhilarating and fantastic hypotheses, often combined with imaginary voyages of discovery necessitating Crusoe-like survival skills. In his book The Man in the Moone of 1638, Francis Godwin described a box kite formation of birds he called gansas, which sound like a large variety of goose, carrying his hero Domingo Gonsales to the moon (Domingo was very small and light, Godwin assures us). Enlightenment writers characteristically combined libertine fantasies with scientific speculation. In The Travels of Hildebrand Bowman (1778), the pseudo-memoirs of a shipwrecked sailor, Hildebrand visits the ‘Powerful Kingdom of Luxo-Volupto’ where he has a wonderful encounter: a winged woman swoops down on him as he is taking a stroll through the town, ‘a tall masculine Alae-puta … [who] clasps me in her arms, mounts into the air, and flies with me about fifty paces; then set me down and run away laughing’. He learns that women in this country grow wings when they commit ‘a failure of chastity’. The more sex they have, the larger and stronger their wings; when they stop misbehaving, their wings dwindle (perhaps a disincentive).

Young doesn’t mention these Alae putae, or winged whores, and mostly keeps to mythological sources. She ends her book, however, with a consideration of actual pilots – aviators like Amelia Earhart and the German Hanna Reitsch, who was in the bunker with Hitler during his last days and lived until 1979. Young connects Reitsch to the Valkyries of Norse myth, as invoked by German Romantics and the Third Reich. She then segues to the women pilots of the US air force in World War Two, four of whom nicknamed their bomber ‘Pistol Packin’ Mama’, and mentions cosmonauts but does not say much about them. Although Young sees Reitsch and others as exemplifying the transition from mythic fantasy to reality, her book doesn’t explore the implications of this: the approach of Women Who Fly is anthropological, rather than philosophical. I wish she had written about Happy Moscow, the heroine of Andrei Platonov’s novel, who, when about to execute a parachute drop from a plane, lights a cigarette: ‘carried by the pull of the vortex, flames at once seized the combustible lacquer impregnating the silk straps that linked the weight of the human being to the canopy of the parachute.’ Like Lucifer, she falls in a ball of fire, and finds on her recovery that she has become an ‘All-Union celebrity’. This savage scene of glory and destruction – a satire on Stalin’s aeronautical ambitions – takes place in the territory between allegory and history, fantasy and reality.

In Images of Flight, Clive Hart tackled the problem presented by tales of flying saints and mystics. He quotes from the extraordinary testimonies to Saint Joseph of Cupertino (b. 1603), ‘the most aerial of the saints, who moved – up, down, back and forth – [and] his clothing always remained undisturbed’. Joseph’s flights – lengthy circuits out of doors as well as inside – were often sparked by a line from a prayer: praise of creation would send him soaring skywards for joy. Hart suggests that ‘because Joseph’s flights are said to have really happened, it is easier to respond to them without total disorientation if the saint is imagined as unthreatening, as familiarly lovable (a child) and at the same time as something that we are not (retarded, and given to strange personal habits).’ Does this apply to the phenomenon of Christina the Astonishing? In what sense can the stories – and eyewitness accounts – of her revival from the dead, her prodigious volatility, be true?

The immense corpus of miracle stories and wonder tales, myths and fairy stories poses difficult questions about consciousness and literature, imagination and pleasure. If we take it that the witnesses and confessors who recounted narratives of levitation and flight were not setting out to deceive, that the compilers of the Acta Sanctorum, the Lives of the Saints, weren’t rogues and liars, then what is language doing in such testimony? The interrogator at Joan of Arc’s trial for heresy was quite serious when he asked her if she could fly. This would have proved that she was in league with the devil and therefore a witch, as many of his contemporaries believed. Stories of flight have historically been as likely to lead to punishment – and death – as veneration. The will to believe such accounts can have terrible repercussions.

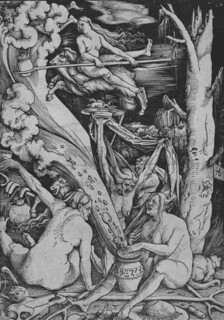

Paul Veyne, the great classicist, wrote a justly celebrated book, Did the Greeks Believe in their Myths?, in which he makes clear that we can’t know the answer. The literal, physical reality of aerial creatures, like that of divine creatures, has undoubtedly diminished in the minds of readers and worshippers. But such figures have not altogether become personifications or allegories. By concluding with pilots, Young tilts towards the embodied end of the spectrum; this is amusing, but a feint. The host of winged hybrids, angels and monsters, if not actually believed in any longer, still have a vividness that is partly a consequence of the wonderfully rich stories they carry with them and the intensely realised visualisations they have inspired, from classical antiquity and Asian artefacts to Baldung Grien’s terrifying and lascivious witches brewing up flying ointment from dead babies and donkey parts.

Are women who fly simply metaphors – for sex and the ambition to transcend? For rapture and possible downfall? To see them as enfleshed metaphors recognises how common parlance becomes active in sacred and secular stories: ‘metaphors we live by’ in the formulation of Lakoff and Johnson. Young quotes in her epigraph from Hélène Cixous’s Le Rire de la Méduse, a founding document of écriture féminine: ‘Flying is woman’s gesture – flying in language and making it fly.’ In the original French, Cixous then takes flight on the associations of voler, meaning to steal as well as to fly. Women are voleurs – flyers and robbers – she declares. ‘We have all learned the art of flying and its numerous techniques,’ she writes, ‘for centuries we’ve been able to possess anything only by flying; we’ve lived in flight, stealing away, finding, when desired, narrow passageways, hidden crossovers … Women take after birds and robbers just as robbers take after women and birds.’

In 1975 this rhapsodic call held out an exciting promise of liberation and resistance but in its sweeping claims it shows the limitations of metaphor (try telling a woman trying to get through a fortified border that she can fly). Its collapse into vacuousness also shows the need to distinguish lexical events from imagined figures like Athena or a merciful bodhisattva descending to earth. ‘We call symbolic,’ the German philosopher Friedrich Theodor Vischer wrote, ‘a once believed mythical element, not objectively believed, yet with the lively backward transposition of a belief that is assumed and taken up as freely aesthetic– not an empty but rather a meaningful phantasmic image.’ Aby Warburg took off from Vischer when he began thinking about the illusory life of such inanimate images, emphasising how crucially historical memory is engaged in their activation. We bring to stories we hear or read or see the baggage of previous knowledge, personal and cultural. The layering of images in today’s technologies of communication and cultural exchange has made the language of past symbols more pervasive and oddly more current. The weightlessness of flying women – and of men and children, divine and magical – doesn’t only reflect dreams of altered states, of bliss and escape, but also the figments made in ‘the balloon of the mind’ and passed through the immaterial media of mass communications and computer-generated entertainments to look convincingly real and solid, even as the images skim, soar and dive through the air.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.