We went to see the Bayeux Tapestry the other day. In January, Emmanuel Macron promised to lend it to Britain, so it seemed worth taking the children to visit it in Normandy before it got dropped in the sea or torn or lost on its way across the Channel (all fairly unlikely, I know, but I’m a pessimist). I needn’t have worried: the tapestry (embroidery, technically, but who calls it that?) won’t be leaving Bayeux until 2023, for a brief period while the museum that houses it is being refurbished – by which time Macron may well no longer be president of France. A lot of his promises seem to turn out like that, a lot less generous than they at first appear.

Before Bayeux we’d been in Bourbon-l’Archambault, not far from Vichy, where we visited the ruined castle that was once the seat of the Bourbon dynasty, a memento mori for the powerful if ever there was one. And the day before that, we’d zipped across the frictionless (though not invisible) border between Italy and France deep beneath the Alps, having trundled past the French frontier guards stationed on the Italian side of the tunnel, who’d been utterly uninterested in our Italian-registered Skoda. Our EU passports were buried somewhere in the boot but we didn’t need them, our white faces documentation enough to allow us to pass freely without let or hindrance.

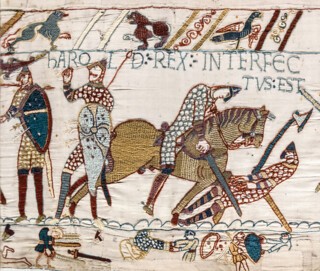

Bayeux was busy with American tourists. The D-Day landings seem to be as much of a draw these days as the Norman Conquest. A poster showed a New Yorker cover from July 1944, depicting the events of Operation Overlord in the style of the Bayeux Tapestry. (A piece of anti-Macron graffiti on another wall showed Marx’s face with the slogan ‘En Marx!’) There were at least as many Stars and Stripes flying as there were tricoleurs or EU flags, as well as adverts for the golf course at Omaha Beach. There weren’t any queues at the Musée de la Tapisserie; we bought our tickets and went straight in, turning down the offer of audio guides, trusting to the succinct Latin captions (or tituli) stitched into the tapestry: ‘hic eadwardus rex … defunctus est.’ That’s clear enough, and most of the story is familiar, though I’d forgotten the bit about Harold helping William to fight the barbaric Conan, Duke of Brittany, and rescuing two of William’s men from quicksand near Mont St Michel.

The story in the tapestry is terrifically well paced (the children occasionally complained of being bored, but shuffling a few steps further on was enough to revive their interest): Harold is crowned king of England just before the halfway mark; William lands in Sussex two-thirds of the way through (‘But I want the English to win!’ my five-year-old son wailed); and there’s no hanging about after ‘harold rex interfectus est.’ The English turn and flee, and that’s that: it’s a bit like Tosca in this respect, or St Mark’s Gospel before the spurious final verses were added. Disappointingly, however, and entirely unlike Mark, it turns out that the end of the original Bayeux Tapestry is missing – it used to be a metre or two longer – and the last titulus, ‘et fuga verterunt angli,’ was added during the Napoleonic Wars. Regardless of any additions and excisions, the tapestry’s narrative is well structured, too, with Harold’s voyage from England to France – there’s a nice scene of two men (I think one of them is Harold) hitching up their skirts to wade aboard – balanced, or outweighed, by William’s formidable invasion fleet in the second half.

In the afternoon we drove up the Cherbourg peninsula to catch the catamaran to Portsmouth. The sea was dead calm under clear blue skies. We made the crossing in less than three hours. (William the Conqueror set sail on the evening of 27 September 1066 and didn’t land at Pevensey till the following day.) Approaching the English coast, we passed the Solent Forts, built by Palmerston in the 1860s to defend against the threat of a French invasion. Two of them have now been turned into luxury hotels. At the beginning of June they were put up for sale. Perhaps they’ll be requisitioned after Brexit by the Home Office for use as customs warehouses (they’ll need somewhere to store impounded antique tapestries) or immigration detention centres. Portsmouth Harbour was full of Royal Navy ships, including the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth. From one angle, the Daring-class air defence destroyers looked like bull terriers; from another, like cans of stockpiled spam.

The far right likes to talk about immigration in terms of invasion – a wave of such rhetoric carried Matteo Salvini all the way to the Italian Interior Ministry – which would be laughable if it weren’t in fact deadly. Since the peak of the immigration crisis three years ago, the numbers of people coming to Europe have been going down, but the proportion of deaths has been going up. In 2015, according to the UNHCR, 1,015,078 people arrived in Europe by sea from Africa and the Middle East, and there were 3771 dead and missing (0.37 per cent). In 2016, there were 362,753 sea arrivals and 5096 dead and missing (1.4 per cent). In 2017, there were 172,301 sea arrivals and 3139 dead and missing (1.8 per cent). So far this year, there have been 51,486 sea arrivals and an estimated 1410 dead and missing (2.7 per cent). More than a third of those deaths (489 and counting) have occurred since 18 June, after Salvini took office and announced that Italian ports would be closed to NGO rescue ships. A petition to the Italian Parliament calling for a vote of no confidence in Salvini has received more than 130,000 signatures, but is still waiting for an opposition MP to take up its cause.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.