In the days before artists brought colour to the cover, the London Review of Books was black and white. Of course, originally, it had no front at all: the first edition, in 1979, was meekly folded into the New York Review of Books. The following year it jumped out of that pouch and into a world where literary journals were routinely typographical. Not all faces around the editorial table lit up when Karl Miller suggested the independent paper should have a giant picture on the cover. You’ll never find enough images, said Mark Boxer. He was wrong about that.

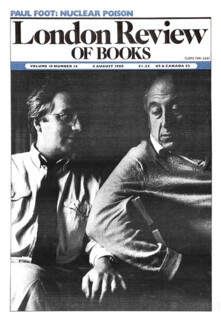

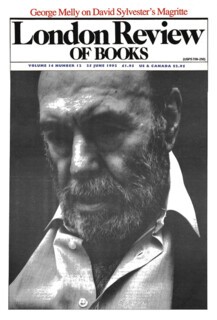

The staff ripped off books for drawings and paintings – and commissioned photographs. Some of the most powerful were by David King. He used to come blazing into the office with his huge black-and-white portraits, already measured up for size: no question, ever, of anything being cropped. One was of the writer Francis Wyndham, then in his sixties, in conversation with a 34-year-old Alan Hollinghurst. It was an extraordinary portrait, the two absolutely at ease but sitting at an angle to each other and looking quizzical. Hollinghurst, clean-shaven and gentle. Wyndham, melancholy and long-cheeked. Intimate but formal. Possibly plotting. One friend remarked that they might have been ‘two cardinals’. King took a magnificent picture of the art critic David Sylvester – and dug up an extraordinary billowing image of Isaac Babel. In 1989 he arrived with a previously unpublished photograph of Jean Genet, which he had taken in the early 1970s. It was the most tremendous close-up: just nose, eyebrows and set mouth. You could count the pores. As he handed the picture over, he described how he had taken it, in a hotel in Lancaster Gate. And he reported an unexpected conversation, which he delivered off the cuff and word perfect. He had remarked how still Genet was.

‘That,’ Genet replied, ‘is because I am dead.’

‘You can’t be dead – you’re the greatest living writer.’

‘No, no, Noël Coward is the greatest living writer.’

‘But Noël Coward is dead.’

‘Oh,’ said Genet, ‘that’s good.’

There was our caption. No editing needed. David had the ear of a natural writer – there seemed to be no gap between what he saw and what he said – though he refused to admit it.

As a young man, he had made his living as a graphic designer, picture editor and photographer. And made a life fired up by ‘heavyweight leftist politics – and art’. He said he had wanted to create ‘a visual style for the left’ and he developed one when working for the Anti-Nazi League (that yellow badge was his), the anti-apartheid movement and on the early issues of City Limits. Rocketing arrows, thick sans-serif type, strong black bands. At the Sunday Times Magazine, where he was art editor for ten years from the mid-1960s, he laid out Don McCullin’s Vietnam photographs over 17 pages, uninterrupted by ads. But at the time of his death, two years ago at the age of 73, his name was most often seen in a quiet copyright line at the end of documentaries about the former Soviet Union: an acknowledgment of the use of material from his collection. Warren Beatty rolled up to consult it when making Reds.

A few months ago in Tate Modern I heard a young woman explaining David King to a group of attentive listeners. He had, she said, ‘no furniture in his house. Just shelves. For the Collection.’ That collection, an extraordinary 20th-century conglomeration, was all around her in the gallery’s exhibition Red Star over Russia: the result of forty years’ fascination with the former Soviet Union, an attempt to recover lost histories. Posters, magazines, newspapers, paintings, postcards, photographs, banners. Zeal, terror, beauty, proclamation, obliteration, falsification.

‘No furniture’ was, well, not exactly falsification but genial exaggeration. King’s vivid home on the border of Islington and Hackney did contain domestic items. But it also held 250,000 Russian artefacts: not in the manner of a fusty depository, but as dynamic display. The terraced house on the Balls Pond Road was made up of pine and scarlet and diagonals. Wooden beams, wooden floors, wooden Venetian blinds, ladders slanted against bookshelves. A Constructivist sculpture, like a demonic snowflake, made by King from black painted wood. Soviet artefacts: a silk banner, a crimson alarm clock, hammer-and-sickle badges. A fleet of scarlet filing cabinets holding photographs, documents and journals. And modern objects which nodded to the Reds: a scarlet drawing board, a scarlet rubbish bin, a scarlet Sellotape dispenser. In the back garden, he had laid out a brick mosaic in the shape of a five-pointed star and put up a bust of Marx: it came from a film set. One friend called the house ‘Trot-ski Lodge’.

What King called his ‘chaos of collecting’ (though it looks organised enough to me) began in 1970 when the Sunday Times Magazine commissioned him to research two picture-driven features on Lenin. He had set off for the Soviet Union after four hours of instruction from Don McCullin, who suggested he use a Nikon F2 camera (King often had to defreeze it on the hotel radiator). He came back with albums and photographs of the Revolution, and a determination to document in pictures the figure missing from his researches: Trotsky. A year later he had gathered enough material for a 15-page cover feature but, in an act of obliteration that almost too neatly echoed its subject, the piece did not appear: an industrial dispute led to the pulping of nearly all the 1.5 million printed copies. He had turned the feature into a photographic biography, with a text by Francis Wyndham. ‘Far from Trotsky being expunged from history,’ Wyndham remarked, ‘it turns out there are more photographs of him than there are of Marilyn Monroe!’

The books that he went on to make look prescient now, almost fashionable: fake news! photoshopping! The Commissar Vanishes (1997) is a history of art and photographs doctored under Stalin – Michael Nyman later set it to music. Ordinary Citizens (2003) showed, for the first time in the West, the faces of those ‘enemies of the people’ locked up in the Lubianka. Photographed in natural light, none of them has the stunned look of the flash-bulb mugshot. Greatly enlarged from their original passport photo size, each brims with expression.

Tate Modern was in the process of acquiring the collection when King died. The industrial building glaring across the Thames at more sedate galleries was in tune with the way he looked at things. Tate became his publisher and Tate gave him space. He created a series of temporary rooms devoted to Revolutionary posters, the images jostling together on the walls. Men with scythes and beetling brows: Long Live the Unshakeable Iron Union of the Working Class and Peasantry! A kerchiefed woman – the Soldier’s Madonna – shielding a child from a Nazi bayonet. A rust-coloured hand clamped round a snake: We Will Eradicate the Spies and Saboteurs, the Trotskyist-Bukharinist Agents of Fascism; King noted that Sergei Igumnov’s illustration is ‘eerily reminiscent of an earlier illustration he made of a red star and sturgeon – for a caviar advertisement’.

The gallery did not try to replicate these energetic arrangements after King’s death, when, having completed the acquisition of his collection, it marked the centenary of the 1917 Revolution. Red Star over Russia was an honouring of the collection and its mighty range: pictures of agitprop trains; Stepanova’s marvellous textile designs; exercise books with covers showing cheery, sheaf-bearing women; Mayakovksy on an ottoman after he had shot himself in the heart. Spread out in a leisurely fashion over six large rooms, the show offered slow revelation and little sense of revolution. The clamour of King’s poster rooms was anaesthetised.

The exhibition’s title came from the prodigious book – a square red slab – which King made of his collection. He called it ‘a fast-forward visual history of the Soviet Union … a heavy bombardment’. It was also rich in anecdote, firing off a story a paragraph. About being mistaken for Jesus Christ on a train to Leningrad, about manoeuvring rolls of film through customs, about an encounter with Nadezhda Mandelstam, sitting beside an icon and a bottle of Valium: ‘That Tatlin. He was always trying to invent things … He even tried to build a stove once in his kitchen. It caught fire and burned his flat. What a fool!’ And about what it was to begin relinquishing the ‘stalagmites’ of material he had gathered over a lifetime.

One evening nearly ten years ago I went to Tate’s Rothko exhibition with King and Francis Wyndham. I have never forgotten seeing King swing through the galleries in his long black coat, round wire glasses and beanie. You could see the canvases in his face: it was as if they had been branded on him. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who was so open and intense in his responses. After a while he said he wanted to show us something else. I assumed it was going to be the work of a different painter. But he led us outside the gallery – to an unremarkable tower block. The façade was entirely concrete, except at ground level, where a lattice-work metal shutter closed the building off from the street. We peered through it: Rothko had set our eyes up for looking at something made up of oblongs. We saw a dimly lit, empty room. It was a rough space that could have been used for storage or as a workshop or a garage. But for a minute, seen through King’s eyes, it became mysterious. Like a mini theatre; both peculiar and ordinary. Better than some of the things in the Tate, King thought. He said he had begun to see spaces like this all over London and had become fascinated by them. It took him to point out that they were particular; that the locking-up of London was producing shuttered-up dramas.

King’s politics went right through him. Even his eye was egalitarian, as I came to realise when I asked him for his memories of Bruce Chatwin, a friend from his Sunday Times days. He had designed a book of Chatwin’s photographs, turning it into a disputatious work of art: in the spirit of a 1930s volume he admired, Art without Epoch, he put a bronze from Benin next to a Mazzoni terracotta head, and the beams and slats of an East Anglian windmill immediately after a ridged tin roof in Senegal. A tree stump in the middle of a misty Patagonian river followed the figure of a solitary woman in the Peruvian desert. He made his own vegetarian point when he placed nuzzling mountain goats opposite a butcher’s shop hung with lumps of flesh.

King could describe the look of a painting or an object, but he could also transmit the feelings it aroused. The objects that he and Chatwin liked were things often taken for granted: art without artists. He talked about the passion for wood that they shared. He made me see that a fish tray from Istanbul – shaped like a garden sieve, shaded in pinks and crimson – could lift your heart as much as a revered painting. He talked about his and Chatwin’s love of utilitarian buildings, ‘sub-architecture’, corrugated iron – they had spent a weekend in the Welsh borders looking for Nissen huts. He also mentioned a paradoxical creation of his own, a piece of wit as well as of craftsmanship. King had built a black lamp: about six feet high, it was made of wood with the bulb sunk into the top so that you couldn’t tell where the radiance was coming from. King’s idea was to make a light that was as un-light as possible.

On the phone one day, he mentioned a chance sighting of Chatwin. The account was pungent: very blond hair, ultra-blue eyes and a bright green jacket. Then King paused and said: ‘It was as if the blue and yellow made the green.’ He forgot he had told me that, and was surprised when I published the exchange. But a few weeks later he did an extraordinarily generous thing. He said he had been making pictures in wood, and that one of them was for me. Bright vertical stripes, of yellow, blue and green: a tribute to Chatwin which has been on my wall ever since. Whether the light is on it or not, it seems always to glow.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.