‘A father is a necessary evil,’ Stephen Dedalus says in Ulysses. In Yeats: The Man and the Masks, Richard Ellmann quoted Ivan Karamazov: ‘Who doesn’t desire his father’s death?’ ‘From the Urals to Donegal,’ Ellmann writes,

the theme recurs, in Turgenev, in Samuel Butler, in Gosse. It is especially prominent in Ireland. George Moore, in his Confessions of a Young Man, blatantly proclaims his sense of liberation and relief when his father died. Synge makes an attempted parricide the theme of his Playboy of the Western World; James Joyce describes in Ulysses how Stephen Dedalus, disowning his own parent, searches for another father.

Just as Oscar Wilde began to become himself the year after his father’s death, when he was 21, and John Butler Yeats managed, figuratively, to kill his son by going into exile in 1907, so too James Joyce managed to kill his father when in 1904, at the age of 22, he left him to his fate in Dublin, returning only for a few short visits. Since his father’s presence loomed so large in the city, Joyce needed to go away so that the man who had begotten him could move into shadow. It was only then that the father could be reimagined and reinvoked in the son’s work.

John Stanislaus Joyce was born in Cork in 1849, to a family of well-to-do merchants and property owners, prominent in local politics. He was sent out to work – his father wanted to build up the boy’s health – on the pilot boats that operated in Cork Harbour, where, as his own son and James’s younger brother Stanislaus would later put it, ‘he learned from the Queenstown pilots the varied and fluent vocabulary of abuse that in later years was the delight of his bar room cronies.’ When he was 18, a year after his father’s death, John Stanislaus went to Queen’s College in Cork to study medicine. He never finished his degree, but enjoyed himself enormously as a student, having a fine tenor voice and becoming involved in amateur theatre. He took up work as an accountant in Cork before moving to Dublin with his mother at the age of 24 to help run a distillery, at Chapelizod on the banks of the Liffey, in which he had bought shares. It wasn’t long before the distillery went into liquidation. Joyce lost his job and most of the £500 – £35,000 in today’s money – he had invested in the company. He began to work as an accountant again, with offices in Westland Row, where the Wildes had once lived and where Oscar Wilde was born. He would walk the city to drum up work, doing the accounts of small businesses and assisting with bankruptcies.

He was a popular fellow and much admired for his singing. His son Stanislaus reported that at a gala dinner in his honour before he left Cork a leading English tenor said ‘he would willingly have given two hundred pounds there and then to be able to sing that aria as my father had sung it.’ In Dublin he sang at concerts and attended recitals where he heard the great singers of the age. He also found a new job as secretary of the United Liberal Club, which welcomed both Liberals and Home Rulers at a time when Isaac Butt’s leadership of the Irish Parliamentary Party was giving way to that of Charles Stewart Parnell. The club, in Dawson Street, was a place to meet and smoke and drink and discuss politics. He played an active part in the 1880 elections to the Westminster Parliament, helping ensure that the two Conservative candidates standing in his constituency were defeated, and a Liberal and a Home Ruler elected. He was given a bonus for his tireless work on the campaign.

At around this time, he got to know May Murray, who was then 19. She had been trained to sing and play the piano by her aunts, who were well known in Dublin’s musical circles. May’s father disapproved of John Stanislaus, and his mother disapproved of May: in May 1880, shortly before their wedding, she decided to return to Cork for good. The Joyces’ first home was on Ontario Terrace, near the Grand Canal – the same address where the fictional Leopold Bloom would live with his wife, Molly. Their first child, born seven months after their marriage, died when he was eight days old. The following year, the Liberal Club closed down, but with the help of his political friends John Stanislaus found work as a rate collector. It was a kind of sinecure, with a salary of around £400 a year, about four times the average industrial wage, and included a pension; soon afterwards, his mother died, leaving him six tenanted properties in Cork, which brought in £500 a year. So by the time James Joyce was born, in February 1882, his parents were well off and could expect a life of some comfort.

John Stanislaus’s work as a rate collector allowed him to get to know the city. The job, which began at ten and finished at four, included a great deal of travelling: his beat included not only the streets close to where he lived but also the more sparsely populated areas around Phoenix Park and along the coast to the south. There was no one to monitor how long he stayed talking in a certain house or how he distracted himself throughout the day: ideal for someone who was sociable and garrulous. The fact that headquarters were in Fleet Street in the city centre meant that when work ended there were many public houses to choose among.

May Joyce had ten children. Between her marriage and her death in 1903 the family moved house as many times. The grandest place they lived was a three-storey, double-fronted building in Rathmines, where they moved in 1884, having been joined by one of John Stanislaus’s uncles and a woman called Mrs Conway, a devout Catholic from Cork, whom James Joyce would immortalise as Dante or Mrs Riordan in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In this house, John Stanislaus would entertain the rising class of Parnellites and his musical friends.

Despite his job and his rents, John Stanislaus found it hard to live within his means, and was forced to remortgage some of his property in Cork and take loans to supplement his income. In 1887, having taken out a loan using his Cork property as collateral, he moved his family to Bray, close to where the Wildes had owned three houses. By now, he was beginning to have problems at work. The authorities were sceptical when he claimed to have been attacked in Phoenix Park and robbed of the cash that he had collected that day. He was transferred to the city centre, where it was easier to keep an eye on him, and he was now often accompanied by an inspector. He took no pleasure in the paperwork, which he often farmed out. His son Stanislaus reported that when deadlines approached ‘he would have a couple of unemployed old clerks scribbling in his house from morning till midnight.’

When James Joyce was six and a half, his parents sent him as a boarder to Clongowes Wood College, a posh school run by the Jesuits. He was rarely home to witness his father’s moods. His younger brother Stanislaus, though, stayed behind, and recounted that their father had become

a man of absolutely unreliable temper. How often do I remember him sitting at table in the evening, not exactly drunk – he carried his liquor too well then – but sufficiently so to have no appetite and to be in vile humour … In later years my mother told me that she was often terrified to be alone with him, although he was not normally a violent man … He would sit there grinding his teeth and looking at my mother and muttering phrases like ‘Better finish it now.’ At one time she thought of getting a separation from him, but her confessor was so furious when she suggested it that she never mentioned it again.

John Stanislaus’s finances became more and more precarious, with moneylenders in pursuit and with rent overdue on their latest house, in Blackrock. There were court judgments against him. Bailiffs seized his furniture, leaving him only the portraits of his parents and grandparents that his son James would eventually take to Trieste with him and proudly display. Late in 1892 or early in 1893, he was forced to move his family to the area around Mountjoy Square on the north side of Dublin. On 1 January 1893, after new rules came into force allowing the Dublin Corporation to collect the rates itself, almost all the rate collectors lost their jobs but were offered a generous severance package: three-quarters of their annual salary as an annual pension, irrespective of how long they had served. Because of his poor record, however, this did not apply to John Stanislaus, who was at first offered nothing and then half what his colleagues were getting. This amounted to one third of his former wage.

Thus at the age of 44 Joyce was living in a sort of aftermath. Having basked in the glory that came from being a supporter of Parnell, who was now dead, he was left to linger in the dullness and rancour that came once the Irish Parliamentary Party had split. And, once more, he had to take any other work that came his way, as accountant or financial clerk. By this time he had nine children to support. By the end of 1893, having already remortgaged much of it, he was forced to sell all the property he had inherited in Cork.

John Stanislaus Joyce was perhaps unlucky that he had lost his job, and unlucky too that he didn’t know how to manage his finances, and that he had so many children to feed, but his worst piece of luck may have been the brooding presence in his household throughout his fall from grace of his second living son, Stanislaus, who described what happened to the family with bitterness and in some detail in two books, both published after his death, My Brother’s Keeper in 1958 and The Complete Dublin Diary of Stanislaus Joyce in 1971. In My Brother’s Keeper, Stanislaus described the household after his father had lost his job: ‘My father was still in his early forties, a man who had received a university education and had never known a day’s illness. But though he had a large family of young children, he was quite unburdened by any sense of responsibility towards them.’ He charts life at ‘the nine addresses which I recollect over a period of at most 11 years’: ‘besides representing a descending step on the ladder of our fortunes … each of them [is] associated in my memory with some particular phase of our Gypsy-like family life.’

There was, he explained, a method in his father’s fecklessness:

Whenever a landlord could not put up with him any longer and wanted to get rid of him, [he went] to the landlord [to] say that it would be impossible for him with his rent in arrears to find a new house, and that it was indispensable that he should be able to show the receipts for the last few months’ rent of the house he was living in. Then the landlord, to get a bad tenant off his hands, would give him receipts for the unpaid rent of a few months, and with these my father would be able to inveigle some other landlord into letting him a house. In these auspicious circumstances we moved into a smaller house in a poorer neighbourhood.

Stanislaus recorded all the drunkenness and the outrages, including a moment when John Stanislaus ‘made a vague attempt to strangle’ his wife:

In a drunken fit he ran at her and seized her by the throat, roaring: ‘Now, by God, is the time to finish it.’ The children who were in the room ran screaming in between them, but my brother, with more presence of mind, sprang promptly on his back and overbalanced him so that they tumbled on the floor. My mother snatched up the two youngest children and escaped with my elder sister to our neighbour’s house.

As James Joyce made his way through Belvedere College and then to University College Dublin and later escaped to Paris, Stanislaus kept a firm watch on his father. On 26 September 1903, he wrote in his diary:

He is domineering and quarrelsome and has in an unusual degree that low, voluble abusiveness characteristic of the Cork people when drunk … He is lying and hypocritical. He regards himself as the victim of circumstances and pays himself with words. His will is dissipated and his intellect besotted, and he has become a crazy drunkard. He is spiteful like all drunkards who are thwarted, and invents the most cowardly insults that a scandalous mind and a naturally derisive tongue can suggest.

He noted also that ‘when Pappie is sober and fairly comfortable he is easy and pleasant spoken though inclined to sigh and complain and do nothing. His conversation is reminiscent and humorous, ridiculing without malice, and accepting peace as an item of comfort.’ In April 1904, he wrote: ‘When there is money in this house it is impossible to do anything because of Pappie’s drunkenness and quarrelling. When there is no money it is impossible to do anything because of the hunger and cold and want of light.’ And then: ‘Pappie is a balking little rat. His idea when he has money is that he has power over those whom he should support, and his character is to bully them, make them run after him, and in the end cheat them of their wish.’ In July 1904, he wrote about the tension between his father and his brother James: ‘Pappie has been drunk for the last three days. He has been shouting about getting Jim’s arse kicked. Always the one word. “O yes! Kick him, by God! Break his arse with a kick, break his bloody arse with three kicks. O yes! Just three kicks!” And so on through torturous obscenity. I am sick of it, sick of it.’ On 6 August he noted that ‘there is no dinner in the house.’

Stanislaus’s diary ends in January 1905. In its place, his younger brother Charlie kept a diary beginning in May that year, a diary that made its way to the library of Cornell University; quotations from it appear in John Wyse Jackson and Peter Costello’s 1997 biography of John Stanislaus. On 26 and 27 and 28 May, Charlie Joyce noted that his father was drunk, and again on 31 May and 1 and 2 and 13 and 14 and 15 June. And on Sunday 24 June: ‘Pappie home to dinner very drunk: shouting, swearing etc. Pappie has thrown his dinner about the floor: Baby [the youngest of the family] white as a sheet: Pappie gone out again: home again: sleeping off some of the drunk.’ Other entries note that one sister pawned her dress as there was no dinner. By this time, Georgie Joyce, three years younger than Stanislaus and five years younger than James, had died a slow and painful death at the age of 15, and May Joyce had died aged 44. Perhaps of all the passages about their father by the Joyce sons, the section in Stanislaus’s My Brother’s Keeper about their mother’s deathbed, to which her son James had been summoned from Paris, is the most harrowing. ‘My father,’ Stanislaus wrote,

was on his good behaviour for the first few weeks but as the illness dragged on he became unreliable and had to be watched. One evening towards the end, my father came home ‘screwed’, as Aunt Josephine called it, after having drowned his sorrows copiously with various friends, and went into my mother’s room. Besides my aunt, my brother [James] and I were both there. My father asked some perfunctory question, but it was evident that he was in vile humour and itching to say something. He walked about the room muttering and then, coming to the foot of the bed, he blurted out: ‘I’m finished. I can’t do any more. If you can’t get well, die. Die and be damned to you!’ Forgetting everything, I shouted ‘You swine!’ and made a swift movement towards him. Then to my horror I saw that my mother was struggling to get out of the bed. I hurried to her at once, while Jim led my father out of the room. ‘You mustn’t do that,’ my mother panted. ‘You must promise me never to do that, you know that when he is that way he doesn’t know what he is saying.’

Stanislaus left for Trieste to join his brother and Charlie went for a while to Boston. The girls in the Joyce family kept no diaries, as far as we know, and they wrote no memoirs, but, as soon as they could, two of them also went to Trieste. One joined a convent and spent the rest of her life in New Zealand. The others found work in Dublin, and left home at the first opportunity. Some of them had very little to do with their father again: he had blighted their lives. After his youngest daughter died at the age of 18 in 1911, John Stanislaus, according to his biographers, ‘could no longer endure living with his daughters and their reproaches, spoken and unspoken. His relations with them all had now become actively hostile in both directions.’ From 1920 until his death in 1931, he lived alone in a boarding house, where it seems he maintained cordial relations with the landlady. For the last 19 years of his life he didn’t see his sons, since they saw no reason to return to Ireland. All that was left in the old man’s room when he died, the landlady’s husband reported, was ‘an old suit of clothes, a coat, hat, boots and stick’ and a copy of James Joyce’s play Exiles.

It would be easy, then, to think of John Stanislaus Joyce as one of the worst Irish husbands and worst Irish fathers in recorded history. But in his older son’s work another picture emerges. James Joyce – from a distance, relying on his memory and on reports – sought not only to memorialise his father, but to retrace his steps, enter his spirit, use what he needed from his life to make his own books. After John Stanislaus died, he wrote to Harriet Weaver:

I was very fond of him always, being a sinner myself, and even liked his faults. Hundreds of pages and scores of characters in my books came from him … I got from him his portraits, a waistcoat, a good tenor voice, and an extravagant licentious disposition (out of which, however, the greater part of any talent I may have springs) but, apart from these, something else I cannot define.

To T.S. Eliot he wrote:

He had an intense love for me and it adds anew to my grief and remorse that I did not go to Dublin to see him for so many years. I kept him constantly under the illusion that I would come and was always in correspondence with him but an instinct I believed in held me back from going, much as I longed to.

And he told his friend Louise Gillet in Paris: ‘The humour of Ulysses is his; its people are his friends. The book is his spittin’ image.’

It is fascinating to watch James Joyce making use of the threadbare and often miserable business of what he knew, what he had experienced, of his father. But he also wavered, as different ways of imagining him collided. In the original plan for Dubliners, the last story was to be ‘Grace’, written in October 1905. The story begins with a real event that occurred to John Stanislaus when he fell down the stairs of John Nolan’s public house off Grafton Street on his way to the lavatory. He was rescued by a friend of his, Tom Devin. As he imagined the story, James Joyce changed the background of Mr Kernan, the man who falls, from that of his father to a neighbour of the Joyces’ called Dick Thornton, a tea-taster and opera lover. The story’s tone is unmerciful. The drinker’s clothes ‘were smeared with the filth and ooze of the floor on which he had lain, face downwards. His eyes were closed and he breathed with a grunting noise.’ The forensic style continues when, having taken the drunk man home, ‘Two nights after his friends came to see him.’ They begin to discuss religion, and propose a retreat. John Stanislaus was persuaded to attend just such a retreat. In the story, the priest who leads it is called Father Purdon: the Dublin reader will get the joke, as Purdon Street was one of the best-known streets in Dublin’s red light district (it will be named in the Nighttown section of Ulysses), but the men themselves aren’t aware of how funny this is. Nor are they alert to their own foolishness as they muse on various popes and their mottoes – from Lux upon Lux to Crux upon Crux. And at the retreat, as they peer at a speck of red light suspended over the high altar and are preached to by Father Purdon, they are comic figures, to be mocked. The jokes in the story depend on their foolishness, their ignorance, their insularity, the clichés they use.

Had Dubliners ended there, Joyce would have taken a suitable revenge on his father. But two years after ‘Grace’, he wrote ‘The Dead’, which eventually became the last story in Dubliners, and it was as though he now sought to resurrect those he had previously buried with mockery. Instead of studying the main character as though for his own amusement, he inhabited it. This story, too, was based on an event in his father’s life, but instead of recounting it he began to dream it, reimagine it and offer it a sort of grace. The Joyces had been at many parties in Usher’s Island, around Christmas and New Year, to see John Stanislaus’s aunts. James was never there, but his brother notes that his father had a ‘glib tongue’ as a public speaker, and says that the ‘gift of the gab’ that Gabriel Conroy exhibits in his speech in ‘The Dead’ is a ‘fair sample, somewhat polished and emended, of his after-dinner oratory’ at the Usher’s Island parties. The quarrel between Gabriel and his mother about his marriage in ‘The Dead’ has elements of the quarrel between John Stanislaus and his mother when he married May Murray. But Gabriel has elements in common with James as well as his father. Gabriel writes book reviews for the Daily Express, as James Joyce did. His wife is from the West of Ireland, as Nora Barnacle was. He is a teacher, as James Joyce was. He has cosmopolitan tendencies rather than nationalist sympathies, like James Joyce.

Joyce found details where he needed them. He began by imagining the house on Usher’s Island, and the twilight time for him as a child when his parents, as a glamorous young couple, went there, a couple united in their love of song, gifted with good singing voices. In the story his father has dignity. It is Freddy Malins who is drunk, not Gabriel. Joyce imagined his parents’ night in all its glowing detail: he saw who else was there; he saw how the evening moved and how it ended. He saw it all so clearly that he seems himself to walk in those rooms in the footsteps of his father. He saw his own partner, Nora Barnacle, there in the place of his mother. He merged his own spirit with his father’s, as he would do later with the river at the end of Finnegans Wake – ‘it’s sad and weary I go back to you, my cold father, my cold mad father, my cold mad feary father’ – or as he invokes his father in the very last lines of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: ‘Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.’

In ‘The Dead’, he moved both himself and his father out of time. To do this, he needed to make a third character, the writer of the story, who, as Joyce with the white page in front of him attempts this grand act of emotional recuperation, lifts up his style, beginning in a tone of pure colloquialism, with the isolated figure of Lily, the caretaker’s daughter, like someone casually telling a story, and ending in a pure tone of high artifice that is close to the language of Pre-Raphaelite poetry or Victorian prayer, with ‘all the living and the dead’. In between, the point of view and the texture of noticed things in the story shift and change. Just as Gabriel – aware of his own inadequacy, his own sense of need – is unsure that his speech is suitable for the occasion, the story itself is unsure, unwilling to settle into a single tone. Gabriel is tentative, caught between two identities, his Irish one and his efforts to escape insularity, as Joyce is caught now between two visions of his father, the one he knows and remembers, and the one he wishes to imagine and bring into being in order to rescue his imagination from a sense of narrow grievance.

The opening sentence of the penultimate paragraph of ‘The Dead’ reads: ‘Generous tears filled Gabriel’s eyes.’ In the mixing of his own sensuality with his imagination of his father’s sensuality, Joyce has banished scrupulous meanness and performed an act of generosity. But his rescue was still tentative. In Stephen Hero, the early version of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen’s father is depicted as someone who ‘was quite capable of talking himself into believing what he knew to be untrue. He knew that his own ruin had been his own handiwork but he had talked himself into believing that it was the handiwork of others. He had his son’s distaste for responsibility without his son’s courage.’ In A Portrait, by contrast, the firmness of judgment has gone: the description of the father is now ambivalent and complex, withholding easy conclusions. Joyce rescues his father from the sorts of certainty that Stanislaus had depended on in his diary and memoirs by moving his father from the private realm, where he is clearly a bully and a monster, into the public sphere – to allow him to be who he seemed to be when he appeared on the street. (Another significant change between the two books: in Stephen Hero, Stephen’s mother is open-minded, able to respond to Ibsen and argue with her son about his loss of faith; in A Portrait, the mother has no interest, other than to represent domestic peace, household activities and religion; she has been consigned to cliché. Her energies won’t be resurrected until Ulysses, when they reappear with haunting urgency.)

There is one episode in A Portrait that moves completely out of the domestic sphere, as Stephen accompanies his wayward father to Cork so that he can revisit old places, rekindle memories, drink a great deal and sell his properties at auction. From the start of the journey, Stephen is uncomfortable: ‘He listened without sympathy to his father’s evocation of Cork and of scenes of his youth, a tale broken by sighs or drafts from his pocketflask whenever the image of some dead friend appeared in it or whenever the evoker remembered suddenly the purpose of his actual visit. Stephen heard but could feel no pity.’ Because his father’s trip is shameful and maudlin, he emerges as pathetic rather than powerful, sad rather than bullying, tedious rather than frightening. Stephen doesn’t despise him – that would be too easy. Instead, in a book about the making of a poet, he listens and watches and lets his mind wander. Stray words come to him powerfully, and confusingly, along with fragments of verse. Guilt about how he himself feels or who he has become fills his mind, as the conversation goes on around him in all its futility. Stephen’s own ‘mind seemed older than theirs; it shone coldly on their strifes and happiness and regrets like a moon upon a younger earth.’ It isn’t merely that he is growing up in these scenes: he is becoming wiser than his father ever was.

Joyce now sought to outsoar his father, to see him as if through sweetened air from high above: he is Icarus, the son of Daedalus, but an Icarus who will fly to avoid what seeks to ensnare him. As he flies, however, his father always follows. Simon Dedalus appears or is mentioned in seven of the 18 episodes of Ulysses. In some of the other versions we have of him, in Stanislaus’s My Brother’s Keeper and in the biography by Wyse Jackson and Costello, where he is installed at home, he is ostracised, but when we meet him first in the ‘Hades’ episode of Ulysses he is fully socialised. He is in a carriage with other men on his way to Paddy Dignam’s funeral. As they travel, the men catch sight of Stephen Dedalus, ‘your son and heir’, as Leopold Bloom points out. As Simon Dedalus rants for a while about the company his son is keeping and what he intends to do about it, Bloom muses: ‘Noisy selfwilled man.’ But then, making clear that he doesn’t see Simon in the way that, say, Stanislaus Joyce sees his father, Bloom continues: ‘Full of his son. He is right.’

Twice, as he speaks, Simon Dedalus is given a good sharp line of dialogue to deliver, establishing him as a witty man with a way with words. Of Buck Mulligan he says: ‘I’ll tickle his catastrophe.’ And then he announces that the weather is ‘as uncertain as a child’s bottom’. In order to anchor the figure of Simon Dedalus in the life of his own father, Joyce allows a moment in which Reuben J. Dodd, someone from his father’s actual life, a man to whom John Stanislaus owed money and whom he disliked intensely, appears on the street. ‘The devil break the hasp of your back,’ Simon says. The modifier here for the verb ‘said’ is ‘mildly’, and it is significant. Simon doesn’t shout at the man or bark the abuse; he doesn’t embarrass his companions by roaring at a man from the carriage. But he makes his views known to them, saying at one point that ‘I wish to Christ’ that Dodd would drown and calling him ‘that confirmed bloody hobbledehoy’.

So by the time he has arrived at Glasnevin Cemetery, Simon has already had two outbursts, however controlled, one against his son and the other against a man who lent him money. For the rest of the journey and in the graveyard itself, he is dignified and treated with respect by those he meets. When the question arises as to whether Dignam, who had died suddenly, was a heavy drinker, Simon says: ‘Many a good man’s fault’, and it is noted that he said it with ‘a sigh’. The next time we see him he is in the offices of the Freeman’s Journal, once more in company where he feels comfortable, comfortable enough to exclaim: ‘Agonising Christ, wouldn’t it give you heartburn on your arse,’ when he is read a piece of overblown writing on the subject of Ireland. Soon he is quoting Byron. And not long after that he is giving ‘vent to a hopeless groan’ and crying ‘Shite and onions’ before putting on his hat and announcing: ‘I must get a drink after that.’

But at this point the real world, or the world of Simon Dedalus’s unfortunate family, makes itself felt, as two of his daughters talk in the kitchen of his house, one remarking, ‘Crickey, is there nothing for us to eat,’ as the other asks where their sister Dilly is. ‘Gone to meet father,’ she is told. The other replies: ‘Our father who art not in heaven.’ And then, close to an auctioneer’s house, the afflicted Dilly meets her afflicted father and asks him for money. ‘Where would I get money?’ he asks. ‘There is no one in Dublin would lend me fourpence.’ Dilly doesn’t believe him. Eventually, he hands her a shilling and when she asks for more, he offers her a tirade of abuse: ‘You’re like the rest of them, are you? An insolent pack of little bitches since your poor mother died. But wait while. You’ll all get a short shrift and a long day from me. Low blackguardism! I’m going to get rid of you. Wouldn’t care if I was stretched out stiff. He’s dead. The man upstairs is dead.’ Eventually, he gives her two more pennies and says he will be home soon. Here he is a man whose children don’t have enough money for food as he himself moves easily in the city, a man more at home with his companions and acquaintances than with his family.

When he appears next, in the company of a man called Cowley, it is significant that Cowley is in even worse financial straits than he is, and is being pursued by Simon’s nemesis Reuben J. Dodd, to whom he owes money. These encounters set a context: they establish that to owe money and fear the bailiff and be poor aren’t attributes that belong to Simon alone; they are treated almost lightly. Up until this point he has been merely a part of the day, another figure who wanders in the book. But in the next episode, ‘Sirens’, which takes place in the bar and restaurant of the Ormond Hotel on Ormond Quay, a building now sadly derelict, he moves towards the centre. It’s worth noting that the Ormond was where James Joyce, during his final visit to Dublin in 1912, had regularly met his father, who was working in some capacity for his friend the solicitor George Lidwell, whose business address John Stanislaus was using as his own.

In Ulysses, at four o’clock in the afternoon, Simon Dedalus, having flirted with the waitress, orders a half glass of whiskey and some fresh water and lights up his pipe. Soon, his friend Lenehan puts his head around the door, and says: ‘Greetings from the famous son of a famous father.’ And when asked who this is, he replies: ‘Stephen, the youthful bard.’

Mr Dedalus, famous fighter, laid by his dry filled pipe. ‘I see, he said, I didn’t recognise him for the moment. I hear he is in very select company. Have you seen him lately?’ He had. ‘I quaffed the nectarbowl with him this very day, said Lenehan. In Mooney’s en ville, and in Mooney’s sur mer. He had received the rhino for the labour of his muse.’ He smiled at bronze’s teabared lips, at listening lips and eyes. ‘The elite of Erin hung upon his lips. The ponderous pundit, Hugh MacHugh, Dublin’s most brilliant scribe and editor, and that minstrel boy of the wild wet west who is known by the euphonious appellation of the O’Madden Burke.’ After an interval Mr Dedalus raised his grog and ‘That must have been highly diverting, said he. I see.’ He see. He drank. With faraway mourning mountain eye. Set down his glass. He looked towards the saloon door.

The ‘rhino’ referred to here is money, and it is clear that Stephen has it. Since Simon’s speech is usually full of wit and texture, his two responses here – ‘That must have been highly diverting’ and ‘I see’ – show him at his most subdued. He is neither the hated father nor the easy companion: he is someone whose son has moved on from him, to spend his time amusing more interesting people. The father’s ‘faraway mourning mountain eye’ is mourning the loss of Stephen.

It would be easy to have him ruminate on this loss for the rest of the chapter, order more drinks and feel sorry for himself before going home to annoy his daughters. But Joyce wants Simon to be a complex figure of moods, an unsettled rather than a solid presence in the book. As well as possessing a talent for not having money, Simon has, as Joyce’s father did, a great tenor voice. In the rest of the chapter, as Bloom ruminates on many matters in the Ormond bar, and George Lidwell, whose real name is used, joins the company, Simon and his companions move towards the piano. Simon manages to make a lewd joke about Molly Bloom, and then sings ‘M’Appari’ from Flotow’s Martha. As Bloom listens, ‘the voice rose, sighing, changed, loud, full, shining, proud.’ This is Simon Dedalus at his most exalted. Bloom notes the ‘Glorious tone he has still. Cork air softer also their brogue.’ Once more, Joyce, in this portrait of his father as an artist, has moved him from resenting his son to becoming Simon Hero among his friends. But Joyce will never let anything happen for long. As Bloom watches Simon, he muses: ‘Silly man! Could have made oceans of money.’ And then in one pithy phrase, he returns the soaring singer to earth: ‘Wore out his wife: now sings.’

The last time that Simon speaks as a mortal in Ulysses is when he muses ‘The wife has a fine voice’ after hearing that Bloom, at one point, has been among the company. The rest of the novel will belong to Bloom and Stephen. The father has been sent on his way as his son moves through the city in search of a surrogate for him. But Simon will soon appear again in the ‘Circe’ episode, in the phantasmagoria that takes place in the brothel. He will be wearing ‘strong ponderous buzzard wings’ and will ask Stephen to ‘think of your mother’s people’ before, in a moment of extraordinary beauty, Stephen’s mother appears to him, ‘emaciated, rises stark through the floor in leper grey with a wreath of faded orange blossoms and a torn bridal veil, her face worn and noseless, green with grave mould. Her hair is scant and lank. She fixes her bluecircled hollow eyesockets on Stephen and opens her toothless mouth uttering a silent word.’ Having said some words in Latin, wearing ‘the subtle smile of death’s madness’, she will say: ‘I was once the beautiful May Goulding. I am dead.’ She will ask him to repent, and suggest that he get his sister Dilly ‘to make you that boiled rice every night after your brainwork’. When she says, ‘Beware! God’s hand!’ a ‘green crab with malignant red eyes sticks deep its grinning claws in Stephen’s heart.’

In the next episode, Bloom remarks to Stephen that he met his father earlier in the day, and gathered in the course of the conversation that he has moved house. ‘I believe he is in Dublin somewhere, Stephen answered unconcernedly. Why?’ Bloom goes on: ‘A gifted man … in more respects than one and a born raconteur if ever there was one. He takes great pride, quite legitimately, out of you.’ He suggests that Stephen might return to live with his father.

There was no response forthcoming to the suggestion, however, such as it was, Stephen’s mind’s eye being too busily engaged in repicturing his family hearth the last time he saw it, with his sister, Dilly, sitting by the ingle, her hair hanging down, waiting for some weak Trinidad shell cocoa that was in the sootcoated kettle to be done so that she and he could drink it with the oatmeal water for milk after the Friday herrings they had eaten at two a penny, with an egg apiece for Maggy, Boody and Katey, the cat meanwhile under the mangle devouring a mess of eggshells and charred fish heads and bones on a square of brown paper.

It is the unconcern in his son’s first reply as much as this stark image of poverty that further consigns Simon Dedalus to the shadows. But, once more, the shadows falter when Simon’s voice comes into Bloom’s mind as he and Stephen walk to Eccles Street, where Bloom lives. Bloom remembers Simon singing the aria from Martha earlier in the day, or the day before as it now is. It was, he lets Stephen know, ‘sung to perfection, a study of the number, in fact, which made all the others take a back seat’. Thus his father’s guilt will be tempered for a second by the memory of his father’s glory.

In the final episode in the book, Molly Bloom’s soliloquy, when Molly mentions living in Ontario Terrace, where John Stanislaus and his wife first lived together, it is as though all along, throughout the book, she and her husband have been pursuing Stephen, whose mother has died, whose father has been cast aside, to become shadow versions of what his parents might have been. In the soliloquy, Simon moves from shadow to substance once more as he is remembered by Molly, singing a duet with her:

… Simon Dedalus too he was always turning up half-screwed singing the second verse first the old love is the new was one of his so sweetly sang the maiden on the hawthorn bough he was always on for flirtyfying too when I sang Maritana with him with him at Freddy Mayers’ private opera he had a delicious glorious voice Pheobe dearest goodbye sweetheart he always sang it not like Bartell dArcy sweet tart goodbye of course he had the gift of the voice so there was no art in it all over you like a warm showerbath O Maritana wildwood flower we sang splendidly though it was a bit too high for my register even transposed and he was married at the time to May Goulding but then hed say or do something to knock the good out of it hes a widower now I wonder what sort is his son he says hes an author and going to be a university professor of Italian …

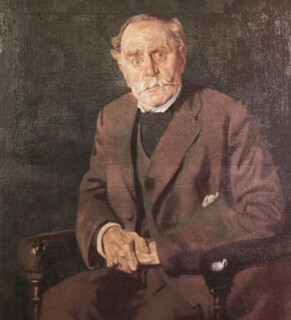

By the time Ulysses came out, John Stanislaus Joyce was living in lodgings with the Medcalf family in Claude Road in Drumcondra, where the best English is spoken. James Joyce, as he became increasingly famous, continued to treasure the family portraits his father had given him and decided to add to them by having a portrait of his father made by the Irish painter Patrick J. Tuohy, which he hung in his apartment in Paris. (Before it left Dublin, the painting was mistitled as a portrait of Simon Joyce, thus merging the two fathers, one from life, one from the books.) Even Stanislaus appreciated the likeness, calling it a ‘wonderful study of the old Milesian … The likeness is striking.’ When, in turn, John Stanislaus was shown Brancusi’s abstract image of his son James, which came in the form of a set of straight lines and spirals, he remarked: ‘Jim has changed quite a bit since I have last seen him.’ The old dry wit had travelled with him.

In Being Geniuses Together, written with Kay Boyle, Robert McAlmon remembered a visit to Dublin in 1925:

In Paris, Joyce had introduced me to Patrick Tuohy, a portrait painter [who] had done portraits of Joyce and of Joyce’s father, and he was now conducting an art class in Dublin. While I was there he took me to see Mr Joyce, Sr., and an amazing old man he was. He sat up in bed and looked Tuohy and me over with fiery eyes, and complained of his weakness. The fact was he didn’t like to exert himself too much, but he rang the bell, and his landlady brought barley water, and the three of us sat ourselves down to a bottle of Dublin whiskey which we had brought. He assured me that he was fond of his son James but the boy was mad entirely; but he couldn’t help admiring the lad for the way he’d written of Dublin as it was, and many a chuckle it gave him. I have never seen a more intense face than that of old man Joyce.

In 1929, around the time of his 80th birthday, old man Joyce received a deluxe edition of his son’s Tales Told of Shem and Shawn. It evokes the image from Finnegans Wake of a ‘dweller in the downandoutermost where voices only of the dead may come, because ye left from me, because ye laughed on me, because, O me lonly son, ye are forgetting me!’ But John Stanislaus Joyce’s son forgot nothing. Six weeks after his father died in 1931, James Joyce’s only grandson was born. The child was given the name Stephen. On the day of his birth Joyce wrote ‘Ecce Puer’. The last stanza reads:

A child is sleeping:

An old man gone.

O, father forsaken,

Forgive your son!

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.