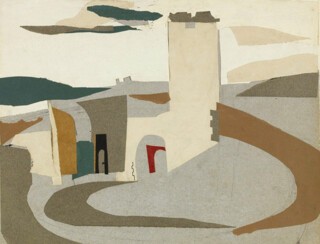

At the start of the war, John Piper – who had made his name as an avatar of high abstraction in the mode of Braque and Mondrian, his paintings hanging among the Giacomettis and Calders in the seminal 1936 show Abstract and Concrete – was struggling to get by. His pictures weren’t really selling, and he was living on the £3 10s a week he still got from his mother. He was 35. Eager for extra income, he took over from Anthony Blunt as the art critic at the Spectator. And he also took on work for the Ministry of Information. His first commission was to paint pictures of the control rooms for the ARP, the air raid precaution service. Where some of the older war artists working on the home front produced suitably boosterish images of British resilience – Paul Nash with his flying boats in Defence of Albion, Duncan Grant with his lush pictures of blooming countryside – Piper wasn’t afraid of a little darkness. In the ARP regional control centre in Bristol he found modernist typography stencilled on the walls, moodily lit corridors, ducts, arrows and piping. He loved it all. His paintings from the scene look like stage sets for a nightmarish play about faceless government bureaucracy.

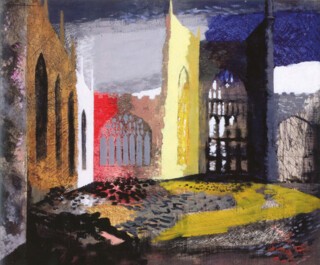

On 14 November 1940, Coventry Cathedral was bombed. Piper was dispatched to record the damage. When he arrived the next morning, the sight of the ruined cathedral, the still blazing fires and the stench of burning, the sight of the ARP officials recovering bodies from the rubble, were all too much for him. He stumbled about, not wanting to get his sketchbook out in the middle of such destruction. Then he came across a row of undamaged houses next to the cathedral, one of which displayed the brass nameplate of a solicitor’s office. It was the sort of place that was immediately familiar to him, and comforting: his father had been a solicitor, proprietor of the family firm, as he too might now be if he hadn’t spent all his time drawing when he was supposed to be clerking. He went in, made his way upstairs, ‘and there was a girl tapping away at a typewriter,’ he remembered later, ‘in a seat by an open window, as if nothing had happened. I said: “Good morning. It’s a beastly time isn’t it?”’ She let him borrow her desk, and he sketched the cathedral’s ruined east façade. Then he went down into the nave and sketched and photographed the view from inside the roofless walls. The painting he worked up ten days later – the tall bands of primary colour in sunlight and shade, red and screaming yellow, the scratched-out sky – was quickly turned into a postcard by the ministry, and it served as one of the more lasting symbols of damage done by the Blitz. ‘John Piper makes us more directly aware of a great architectural tradition burning up,’ Stephen Spender said. Piper – always, temperamentally, happy to comply – went on tour around the country to document burned-out churches as well as picturesque buildings deemed to be under threat, including Windsor Castle, producing a series of dark watercolours with glowering skies. ‘You seem to have had very bad luck with your weather, Mr Piper,’ the king is said to have commented when he saw them.

It isn’t immediately obvious how in the space of five years an artist could have come to be both a pioneer of international modernism in Britain and a dainty recorder of English country houses. In the mid-1930s Piper, as secretary of the influential Seven and Five Society on Ben Nicholson’s recommendation, was making collages with cut-up newspapers in imitation of Cubist papiers collés; he made constructions from string, experimented to find out what could be done with a single flowing line and painted superimpositions of moving forms. Myfanwy Evans, who had charmed Hélion and Kandinsky in Paris and became Piper’s second wife, involved him in every aspect of the avant-garde magazine Axis, which she launched in 1935 and edited through eight difficult issues – it championed the work of Arp, Brancusi, Calder, Domela etc to sceptical London gallery-goers. Even the more ambitious visitors struggled to understand Piper’s most challenging work; after an exhibition in a Hampstead theatre foyer which included some of his ‘alarmingly precise and complex’ abstract constructions, one perplexed reviewer wrote of the ‘hunks of cable, rods, drums, ribbed lavatory panes, strips of perforated bluebottle-metal etc’ that ‘suggest underground wiring diagrams, or nightmare relief maps such as a neat and gifted electrician might improvise in sleep’.

But this forbidding modernist figure, this austere representative of the European cutting edge, has very little in common with the John Piper who is today a much loved minor English institution, who over the past couple of years alone has had exhibitions devoted to him in a whole series of country towns – Chichester, Hastings, Henley-on-Thames – as well as in Mayfair. Those shows were filled with his studies of vernacular and classical architecture, landscapes across England and Wales, textiles and tapestries, designs for stained-glass windows and ecclesiastical vestments. This John Piper was ludicrously prolific, designing sets and costumes for theatre and opera, choreographing firework displays, painting murals, making ceramics and doing typography and dust-jackets and the occasional bookplate for his eminent friends the Sitwells (Osbert paid him handsomely, Edith knitted him a jumper). Betjeman commissioned him to write the Oxfordshire volume of the Shell Guides, a series aimed – as Betjeman put it – at the ‘plus-foured weekender who cannot tell a sham Tudor roadhouse from a Cotswold manor’; Piper took over the general editorship in 1967. This John Piper was eclectic but approachable, and deeply interested in ordinary English things.

How are these two very different artists related? How, indeed, can they be the same person? Piper’s first biographer, Anthony West, promised an answer in a cryptic letter to his publisher: ‘I have had time to work out the rationale for the split between abstract knowledge Mr P., and the old mossy gothic Mr P., which makes sense to me.’ When it was published in 1979 the finished book explained no such thing, and it is still hard to work out the rationale, even when you look for it in David Fraser Jenkins and Hugh Fowler-Wright’s The Art of John Piper, a nearly exhaustive survey of his career in all its phases. Fraser Jenkins, who curated the Tate’s 1983 retrospective on the occasion of Piper’s 80th birthday, knows the career well, and suggests a few possibilities. Piper wasn’t the only British artist to turn away from abstraction at a point towards the end of the 1930s when it all came to seem rather hermetic. ‘The looming war,’ he later said, ‘made the clear but closed world of abstract art untenable to me.’ It hardly seemed democratic, and – unlike, say, Ben Nicholson, who felt any deviation from abstraction as betrayal – he was democratically inclined. Modernism, he believed, could be for people. Invited to explain his work for the BBC series To Unemployed Listeners: This and That, he put it simply: ‘They are not meant to be like anything. They’re just arrangements of shapes and colours that are good to look at – in themselves and for themselves.’ (Unemployed) listeners could even try their hand at it at home: ‘Get scraps of coloured paper (the brighter the better and some with patterns), and some paste, and cut the paper into simple shapes and paste them on the white paper in arrangements that please you.’ Scraps of coloured paper: it was really just a way of having fun.

The best way of seeing Piper is through Frances Spalding’s joint biography, John Piper, Myfanwy Piper: Lives in Art (2009). They met in 1934, at a cottage on a Suffolk beach which Ivon Hitchens had borrowed for the summer for his friends to paint and swim from. Myfanwy was 23 and just out of Oxford, and it didn’t hurt that when she arrived, to be picked up by John from the station, the ‘night was warm and the sea phosphorescent. We bathed before going to the cottage and dried ourselves by running along the strip of sand between the shingle and the shining water.’ John’s previous marriage, to the artist Eileen Holding, didn’t last much longer, and they were soon scouting for a house to rent together. Driving through the Chilterns they passed a derelict farmhouse – empty apart from the chickens – and after climbing in through a window to look around they made inquiries at the local pub and arranged to rent it for £1 a week. They moved in early in 1935, along with the entire print run of the first number of Axis. They didn’t bother installing electricity for the next twenty years but they kept a pig, paintings and a lot of books. Fawley Bottom (Betjeman, a frequent visitor, liked to call it ‘Fawley Bum’) was close enough to London and its galleries; there was plenty of room to work in; and they could entertain. Calder came to stay and fashioned them a pair of chairs from the joists in the kitchen ceiling. After dinner they’d invite their endless guests to a game of consequences, church-style: each person would draw the next bit of a church onto folded paper – nave, chancel, ridiculous transept – with the aim of coming up with more and more outlandish designs. (The art crowd in Hampstead favoured a taxing after-dinner memory game that Ben Nicholson always won.) Nobody ever wanted to leave.

Meanwhile, Myfanwy wrote – librettos for Britten’s operas, articles for Axis and the Statesman – and cooked and made the beds and answered the letters and looked after the (eventually) four children. She also encouraged – or tolerated – any amount and any type of work Piper wanted to do. Often this involved driving great distances with a sketchbook. ‘JP is doing a drawing in a churchyard in a howling wind,’ Myfanwy wrote to a friend from a grass verge in Snowdonia in 1946, ‘and both children and I are in the car and they are either shaking or shouting or asking me for a pencil or paper or hurling insults at each other and it’s frantic and my feet are cold.’ They went on trips anywhere, from Yorkshire to Rome. It turns out that hunting for and collecting ruins and the picturesque, indeed stones and monuments of any kind, wasn’t, as Piper sometimes suggested, something the war had driven him to do. It was a habit and an obsession from an early age. As a boy on family holidays with his parents he would fill exercise books with careful sketches of the churches he insisted they visit, hoping to outdo the guidebooks, and before his father died and he was able to give up the law, he spent lunch breaks sketching the streets near the office in Pimlico (which was also handy for the National Gallery at Millbank, now Tate Britain, where he could look at the Turners and James Ward’s inspiring Gordale Scar).

But these pictures were never academic studies, and they were often playful. There’s an early watercolour view across Vincent Square to the townhouses on the far side that looks like a stage set, with debonair types strolling across the green arm in arm as if it were the place des Vosges. There’s nothing fine-artish about it: it’s like a scene by Dufy, an entertainment. His student work, even before his stint at the Royal College of Art, used features of buildings or street furniture as an invitation to come up with bold graphic arrangements: a sketch in pen of the village green in Witney foregrounds the vertical marks of a fence that form a long running band at the bottom of the frame; the trees to the side function like proscenium curtains. The modernism Piper was born into was the theatrical kind that was in the air and on the stages of London at the turn of the 1920s, when he was learning to draw. His first encounter with what Picasso could do was through the Ballets Russes, and he never stopped loving theatre, opera, drama, a sense of show. But his more antiquarian interests had an equally strong bearing on his work. There’s a striking photograph of a corner of his studio as it appeared in 1936. On the wall is one of his abstracts, featuring repeated Braqueish upright figures suggestive of nudes on a beach. Below it, among the brushes and pots of paint, is a Calder-like construction. And there, too, is a blown-up print of a medieval stained-glass window. The abstract and the church window are speaking the same language. You get the feeling that when he painted the broken nave of Coventry Cathedral as a series of flaming stripes of colour, he wasn’t imposing modern forms on an image of modern destruction so much as exposing the abstract forms that were always there, in the fabric of the church.

The most interesting of the recent Piper exhibitions was at Pallant House in Chichester, just down the road from another cathedral, where one of his more magisterial tapestries hangs behind the high altar. (The tapestry – seven panels sixteen feet high – was installed in 1966. Its central section in searing red represents Christ’s blood; an ox’s head standing in for Luke the Evangelist looks like one of Picasso’s bull’s heads. One of the canons wore dark glasses to its Evensong consecration.) The show’s ostensible focus was Piper’s textiles, but it took in paintings too, including one of the 1935 abstracts, now in a private collection: vertical blocks of colour – grey, black, blue, brown, red, yellow – on a white ground. At Pallant House it hung alongside a version screen-printed on cotton satin in 1955, when the fabric purveyors David Whitehead Ltd commissioned a design from Piper to add to their collection of textiles from Terence Conran et al. There’s something ingenious – and parsimonious – about the way Piper was able to repurpose a piece of 1930s high-art abstraction as modernist chic for a 1950s domestic setting. The original pattern shifts and repeats shimmeringly on the fabric: Piper knew how a curtain works. To his gallerists in the 1950s at Marlborough Fine Art, his forays into design – whatever the material, whether it was cloth, ceramic, mosaic-work or stained glass – were time-wasting distractions that might do lasting damage to his reputation. Well, so be it. Piper himself didn’t seem to care much for the distinctions between the many media he worked in: it was all about using and reusing the materials he so compulsively collected. The best thing in the exhibition was a fabric commissioned for Arthur Sanderson & Sons’ 1960 centenary. It was called ‘Stones of Bath’. Bits of bridges, doorways, roofs, segments of river, are broken up and repeated, his favourite motifs from the city’s neoclassical architecture overlapping with geometric shapes in a bursting arrangement of colour. In his enormously wide-ranging and restless career, Piper seemed to be equally at home in any format, but the basic building blocks remained the same.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.