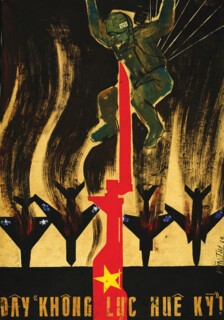

Two exhibitions that opened within blocks of each other in Chicago this autumn make clear the continuing challenges involved in writing Vietnamese history. One, Hunting Charlie at the Pritzker Military Museum, features a collection of North Vietnamese and National Liberation Front wartime propaganda posters. The posters themselves, seldom seen outside Vietnam, are fascinating. But even Trinh Thi Ngo, ‘Hanoi Hannah’, the notorious broadcaster for the Voice of Vietnam who died in September, might have raised an eyebrow at the exhibition’s own propagandistic angle. A caption under a poster celebrating the North Vietnamese victory in April 1975 reads: ‘Given the purges, the mass killings, re-education camps and refugee crisis it bears asking if Ho Chi Minh’s vision of a unified Vietnam for the good of the Vietnamese people was achieved.’

Interspersed with what the curator calls the ‘chilling reality’ of Vietnamese propaganda, the exhibition offers opinions of its own. Framed pull-quotes from interviews with American servicemen remind us that ‘We won the Tet offensive. We decimated the Viet Cong. And our wonderful press made us losers.’ The exhibition portrays the United States as the real victim of the Vietnam War and sees the North Vietnamese as callous and bloodthirsty puppets of international communism. While discredited by most (though not all) academic histories, belief in Vietnam as a noble war is enjoying a popular resurgence in the US.

Just down the road from Hunting Charlie, at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, a very different evocation of the Vietnamese past was on display. The Propeller Group, a Saigon-based artists’ collective, was showing its film, The Guerrillas of Cu Chi. The tunnels of Cu Chi, built by southern Vietnamese communists in a rural area outside Saigon, acted as a logistics centre during the war and survived several American efforts to destroy them. Now they are a tourist destination; some of the tunnels have been enlarged to accommodate Western visitors, who get a chance to fire original Soviet-made AK-47s.

The film documents what happens on the shooting range. The camera moves back and forth on a track behind the targets, showing the tourists being set up with weapons by Vietnamese ‘guards’ dressed in military fatigues. It captures their reactions – intense concentration, laughter and high-fives recorded by friends wielding cameras and phones – as they play soldier. We hear the shots, but only see the reactions of the participants. A 1960s English-language propaganda film called Cu Chi Guerrillas, projected onto the opposite wall at the same time, encapsulates the official Vietnamese narrative of the war: heroic soldiers, workers, peasants, mothers and children unselfishly confronting ‘the merciless Americans’ who ‘ruthlessly decided to kill this gentle and small piece of the countryside’. Visitors could stand between the two films, with communist wartime propaganda on one wall and tourists inhabiting the neoliberal space of leisure consumption in contemporary Vietnam on the other. The tourists were shooting at them.

The complexities of the Vietnamese past are shrouded in myth. One is Vietnam as a ‘little China’, the view that anchored Frances FitzGerald’s still widely read 1972 Pulitzer Prize-winning Fire in the Lake. FitzGerald borrowed from French Orientalists who lamented the ‘vulgarisation of Chinese civilisation’ in Vietnam. Centuries of what they saw as a Confucian-inspired Vietnamese monarchy, and a popular belief in the mandate of heaven that legitimated kingship, had determined Vietnamese understanding of the challenges of the colonial and postcolonial worlds. The success of the North Vietnamese, FitzGerald argued, rested on the popular image of Ho Chi Minh as an embodiment of the Confucian virtues of an ideal Sinicised Vietnamese emperor. American policymakers also used the little China framework, derisively viewing the Vietnamese through a set of racialised hierarchies and classing them as ‘primitive’, ‘lazy’ and ‘vain’. They worried that the Vietnamese postcolonial elite was especially susceptible to outside direction, and that Soviet and Chinese influence would have to be countered by American tutelage.

Most Vietnamese have sought instead to root the country’s origins in an imagined thousand-year history. In this telling, Vietnam was forged as an ethno-national state as it attempted to beat back Chinese campaigns to conquer and control its territory. Vietnamese schoolchildren learn of heroes such as Ngo Quyen, who ended a thousand-year Chinese occupation in 939 by planting sharp wooden stakes at low tide in the bed of the Red River. When the tide rose the stakes became invisible to the unsuspecting Chinese and impaled their armada. Heroism and guerrilla resistance became second nature to the Vietnamese and shaped their later opposition to French colonialism. Examples of patriotic resistance were used again to ground the Vietnamese communists’ opposition to the Americans.

Embedded in such accounts is a conception of state formation known to Vietnamese historians as Nam Tien, or ‘the march to the south’. As the Vietnamese moved south, the story goes, they gradually assumed control of what they perceived to be virgin land. In Vietnam this is seen as a largely peaceful process, but these territories were home to Khmer, Cham, overseas Chinese and a host of ethnic minorities, few of whom were especially keen on becoming Vietnamese. Conquest was seldom peaceful, and sometimes led to what we may now describe as ethnic cleansing. The official Vietnamese story of the country’s origins, in itself not so different from what were once the dominant narratives of the settling of the American west and the Russian east, demands fealty to the idea of an ethnically homogeneous nation.

It’s not quite fair to say that this is where our understanding of Vietnamese history sat before the appearance of Christopher Goscha’s magnificent volume. Goscha draws on the increasingly sophisticated postwar scholarship that wore away at those shibboleths. With the country closed to the non-communist world until its embrace of market-oriented economic reforms in the mid-1980s, historians turned to Vietnamese-language sources held in French libraries and archives. Colonial-era French censors had demanded that a copy of all published Vietnamese texts be deposited in Paris, inadvertently preserving a rich collection of political, philosophical and imaginative works in which Vietnamese writers tried to make sense of French rule and colonial modernity, reinventing themselves in the process. New forms of political thought and practice – republicanism, constitutionalism, socialism, communism in its Marxist, Leninist, Stalinist and Trotskyist variants and other forms of radical politics – all played a part in these transformations.

Younger Vietnamese in the 1920s and 1930s rethought their relationships with their families and adopted an individualism that broke with prevailing social constraints. When French colonial censorship eased in the 1930s, writers lampooned what was seen as an outdated Confucianism, championing the rights of workers, making legible the lives of the urban and rural poor, opposing what they increasingly saw as the oppression of arranged marriages and even writing approvingly about homosexuality. The notion of 20th-century Vietnam as a little China was increasingly unsustainable, but the sense of a Vietnamese tradition that collided with colonial modernity remained. Indeed, one of the most important works in this first wave of historical revisionism was called Vietnamese Tradition on Trial. That tradition was still seen as Confucian, and there was a lingering conviction that the major subject of modern Vietnamese history was the gradual emergence of the nation-state.

Goscha’s book represents the culmination of the last two decades of scholarship on Vietnam, years in which the singularity of Vietnamese tradition has been challenged and the question raised of what a concern with ‘Vietnamese’ history has concealed about the pluralities of its past. Rather than writing only about ethnic Vietnamese or kinh, Goscha draws attention to the country’s heterogeneity and to the Vietnamese as colonisers. Present-day southern Vietnam, for instance, could easily have become part of Cambodia: Khmer kings controlled much of the Mekong Delta into the 18th century. The cosmopolitan kingdom of Champa ruled substantial portions of central Vietnam until the 15th century, overseeing a trade in luxury goods between the Indian Ocean and Chinese markets in a polity shaped by Islam and Hinduism as well as Buddhism. Problematically for those who take the traditional view of Vietnamese patriotic resistance to foreign invaders, a powerful Cham king sacked and looted Hanoi in 1371. The late 15th century marked the beginning of a new imperial project in the southern lands, with Vietnamese emperors undertaking increasingly successful military campaigns in these Khmer and Cham-dominated territories. By the early 19th century, the Nguyen emperors were demanding assimilation from the vanquished Cham and Khmer who remained in what had become southern Vietnam. At the same time they sought control over the Tai and other minority peoples who populated the central highlands. One of the main themes of Goscha’s history is the complexity of governance in these areas and the urge to erase their multi-ethnic character. The Nguyen dynasty, French empire builders and the postcolonial state all struggled to assert administrative control and to subordinate the heterogeneous peoples of the highlands and the south to what they perceived to be the national interest.

Vietnamese religion occupies a central place in Goscha’s account. He demonstrates that Confucianism was only one of many options for the Vietnamese: a ‘world of spirits, local cults, deities, soothsayers and millenarian beliefs’, he writes, permeated ‘the lives of elites and commoners alike’. Buddhism arrived in the third century BCE. Vietnamese emperors before the 15th century, many of them educated in Buddhist pagoda schools, practised a form of rule that drew simultaneously on Chinese statecraft, charismatic familial leadership and Buddhism. The move towards Confucian models of governance came very late, most intensively under the 19th-century Nguyen dynasty, and were no match for the French colonial onslaught.

Like Confucianism, Buddhism in Vietnam was neither monolithic nor static. Folk practices and millennial movements challenged state-sponsored Buddhism if not the imperial state itself. A Buddhist revival in the early 20th century, in part informed by dialogues between modernisers in China and Vietnam, offered a powerful alternative way of thinking about the way the country was changing under French rule. The revival brought an explosion of new Buddhist publications and associations in the 1920s and 1930s that urged social action to help those whose lives were most at risk in the new colonial economy. Catholicism, which first came to Vietnam in the 16th century thanks to European missionaries and their local partners, also flourished in the colonial period as faith became indigenised. Catholicism was sometimes an agent or enabler of French rule, but was just as often in conflict with it. Most Vietnamese were (as they still are) at least nominally Buddhist, and Catholics never made up more than 10 per cent of the population. But Goscha helps make clear the social and political significance of all these different religions.

The Buddhist protests of 1963 in southern Vietnam against the government led by Ngo Dinh Diem, known at the time thanks to the global circulation of photographs of self-immolating monks, are a case in point. The majority of Western observers in the 1960s and later, who saw the conflict through a Cold War lens, perceived religion as a minor element in these protests. Diem’s Catholicism was widely known but seen as a component of his anti-communism, while the Buddhists were usually depicted as dupes or active agents of Vietnamese communism. Viewing it against the backdrop of imperial and colonial history, Goscha shows that faith and its complicated relationship with Vietnamese politics should be at the centre of the story. The robust organisation that emerged from the colonial-era Buddhist revival didn’t need communist backing to protest against the excesses of the Diem government. Goscha also notes that Diem’s crackdown on the protesters echoed the earlier efforts of Vietnamese emperors to rout the Catholics, whom they saw as a threat to their state-building projects.

These tensions remain in present-day Vietnam, where a nominally socialist one-party state overseeing the construction of a market economy confronts a resurgence of religious expression. As well as Buddhism and Catholicism, local cults operating outside the reach of the state claim millions of adherents. More than a million people have visited the shrine of the Lady of the Realm, Ba Chua Xu, in southern Vietnam every year since the early 1990s: religion seems to offer the solace that the state can no longer provide, given the economic, social and cultural dislocations of the market economy. Buddhist monks in Hue recently sat down in the street at major intersections to protest against growing social inequality. The political tensions between religious groups and the Vietnamese imperial, colonial and postcolonial state, invisible in older narratives of the country’s history, allow us to make sense of its more recent past.

The attention Goscha gives to these continuities allows him to place the American war in Vietnamese history without indulging in the usual polemics. American historians of the war have produced thousands of books and articles, but historians of Vietnam have been comparatively slow to discuss the war, partly because Vietnamese-language sources have only become available over the last couple of decades. Even now the Vietnamese state strictly controls what researchers can and can’t see. But shopworn portrayals of northern and southern Vietnam at war are being challenged. South Vietnam, largely dismissed by wartime critics as a creature of the Americans, is now treated in more depth. Diem is no longer an American puppet but a stubbornly independent figure with his own vision of a postcolonial future. The history of North Vietnam, too, is treated more critically than it was during and immediately after the war. There has been a focus on the increasingly authoritarian character of the state as the war progressed, on the schisms within the Communist Party and between northern and southern communists. These developments are welcome, but the new histories can still sometimes seem restricted by a Cold War framework: earlier interpretations that demonised the south and lionised the north are reversed to make a retrospective case for American support of the south against the northern communists.

Goscha resists these inclinations. The American war gets two of his 14 chapters, while late imperial Vietnam and the French colonial era get eight. The war is set in context. As Goscha writes, ‘territorial integration, state centralisation, bureaucratic rationalisation, economic development and ideological homogenisation’ in Vietnam didn’t start with the Americans, or with the coming of French colonial rule in 1858. Projects of ethnic homogenisation didn’t begin with them either. Such processes, glossed by the French and Americans as ‘modern’, were embedded in an earlier imperial state-building project, one that influenced the development of the French colonial order and helped to form postcolonial Vietnam.

Since his driving concern is the history of state-making across imperial, colonial and postcolonial divides, Goscha has less to say about social history. The textures of urban or rural lives, inside or outside the family, wealthy or poor, male or female, kinh, Khmer or Cham, straight or gay, are largely put to one side. Beyond a quick glance at the marvellously ribald forms of colonial-era Vietnamese satire, we don’t get much sense of the sly humour through which many Vietnamese make sense of the world around them. How might Vietnamese people see their past and its relevance to the present? In 2011, the Propeller Group commissioned the best-known advertising agency in Vietnam to rebrand communism in the wake of more than three decades of market economic reform. A new communism, they were told, required a new look. To start with, a new typeface and colour palette were required – the agency recommended the ‘more inclusive’ Gotham Rounded Book and an ‘open, friendly, approachable and welcoming’ gradient of communist red – for redesigned flags, official publications, TV commercials and a vigorous online and social media presence. Banners with the hammer and sickle and the omnipresent images of Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam’s streets were to be replaced with a ‘communist smile’ and the hashtag ‘#communist’. In the words of their proposed new communist manifesto:

Share the world

Live as one and speak the language of smiles

This is the new Communism

Everyone’s Equal

Goscha’s book helps us to see that ‘imperial’, ‘colonial’ and ‘postcolonial’ need some reworking too.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.