Rupert Brooke died of septicaemia caused by an infected mosquito bite, on his way to fight in Gallipoli in April 1915. It wasn’t a romantic or heroic death, but it proved easy enough to turn into legend: that he died in the Aegean and not a ditch in Northern France helped; so did his burial on the island of Skyros, where Achilles lived and Theseus was killed; so did the speed with which his death followed on the publication of his five war sonnets, his most famous and least typical poems, which had just been praised by the dean of St Paul’s for their ‘pure and elevated patriotism’. Churchill’s threnody to an already mythical soldier-poet appeared in the Times three days after his death: ‘Joyous, fearless, versatile, deeply instructed, with classical symmetry of mind and body, he was all that one would wish England’s noblest sons to be in days when no sacrifice but the most precious is acceptable, and the most precious is that which is most freely proffered.’ It was Churchill who, as First Lord of the Admiralty, had formed the Royal Naval Division, secured Brooke a place in it and sent it east, in the hope of helping Russia by taking Constantinople and opening up the Black Sea. In the weeks after Brooke’s death landings were finally made on the Gallipoli peninsula and many of his battalion were gunned down by Turks positioned on the high ground; 11 of its 15 officers were lost by the end of June.

Brooke was buried a few hours after his death in an olive grove on Skyros: it was ‘as though one were involved in the origin of some classical myth’, F.S. Kelly, who would survive until the Somme, noted in his diary. Brooke and his fellow officers, all public schoolboys who’d studied Greek, had been carried away by the Homeric echoes of their journey: ‘Do you think perhaps the fort on the Asiatic corner will need quelling,’ Brooke had written, ‘and we’ll land and come at it from behind and they’ll make a sortie and meet us on the plains of Troy?’ They were primed to see Brooke’s death at this time, in this place, in those terms. They were also aware that their own deaths might well follow swiftly and that, as Denis Browne, who would die in trench fighting in Gallipoli that June, wrote, ‘there’s no one to bury me as I buried him.’ The scene, in any case, was impossibly romantic. ‘Oc’ Asquith, the prime minister’s son (who would survive, though he had a leg amputated), described it to his sister Violet: ‘the moon thinly veiled: a man carrying a plain wooden cross and a lantern leading the way: some other lanterns glimmering: the scent of wild thyme’.

The people who read about Brooke in the papers knew nothing of this, and nothing of his charm and beauty (Leonard Woolf: ‘His looks were stunning – it is the only appropriate adjective’; W.B. Yeats: ‘the handsomest young man in England’; H.W. Nevinson: ‘the whole effect was almost ludicrously beautiful’). The principal driver of myth-creation was the sonnets, whose notion of willing sacrifice in a noble cause had unerringly caught the public mood in this early uncertain period of the war. He was being turned into a ‘poster-poet’, Harold Monro, the editor of Poetry Review, wrote, but ‘“He did his duty? Will you do yours?” is hardly the moral to be drawn.’ Maybe not, but it was handy for the government all the same. Soon enough, the myth of the heroic soldier-poet was joined by that of the ‘young Apollo’: 1914 and Other Poems appeared in June with a frontispiece showing the dazzling bare-shouldered Brooke in profile (‘your favourite actress’, some of his friends labelled it). He was, Henry James wrote, ‘in an extraordinary degree … a creature on whom the gods had smiled their brightest’ (James had fallen hard for what Brooke called ‘his fresh, boyish stunt’).

In 1918 his Collected Poems were finally published, together with a memoir by Eddie Marsh, Churchill’s private secretary and Brooke’s London landlord. Marsh, part of whose income derived from the ‘murder money’ given to the descendants of Spencer Perceval, the only British prime minister to be assassinated, enjoyed cultivating decorative and talented young men whom he could show off around town (Ivor Novello was Brooke’s successor). Brooke’s redoubtable mother had made Marsh rewrite the memoir several times: she felt he’d been an unwholesome influence (which probably means she knew he was a homosexual) and was presuming on Brooke’s decision to make him his literary executor. The result was an airbrushed version of those aspects of Brooke’s life that Marsh and Mrs Brooke knew about, and there were many about which they knew very little. ‘This life,’ one reviewer wrote, ‘slips by like a panorama of earth’s loveliest experience.’ Virginia Woolf reviewed the book for the TLS, trying to remedy the relentless superficiality of the stitched-together letters and reminiscences by hinting that far from being Marsh’s sunny figure, Brooke was ‘the most restless, complex and analytic of human beings’. In private she called the memoir a ‘disgraceful sloppy sentimental rhapsody’ and Brooke himself ‘jealous, moody, ill-balanced’. There was a suggestion that James Strachey should write ‘something for us to print [at the Hogarth Press]. He’s sending us the letters to look at.’ Strachey had offered a review – it never appeared – to the Cambridge Magazine: ‘I knew him better than many people and it would give me a good deal of pleasure to try and explain what he was really like … If I wrote it would be something rather scandalous.’

Strachey was for several years one of Brooke’s closest friends. Their letters, which are full of gossip about the homosexual affairs of their fellow Cambridge Apostles and rake over in Bloomsbury truth-telling style Strachey’s own hopeless passion for Brooke, didn’t give the version of Brooke that Marsh and his successors wanted to portray (when Brooke’s mother died in 1930 her will replaced Marsh with four men she liked better). The most active of the new trustees, Geoffrey Keynes, brother of Maynard (‘the iron copulating-machine’ whose exploits are much discussed by Brooke and Strachey), was distressed at the idea that people might think Brooke was gay because Marsh, as Keynes put it, had ‘lived in a sexual no-man’s-land whose equivocal aura pervaded the memoir’. The correspondence with Strachey would be published, he said, ‘over my dead body’, and when he edited the 700-page volume of Brooke’s letters that finally appeared in 1968 he didn’t include any of it and cut passages elsewhere that seemed damaging to Brooke’s reputation. (Keith Hale, who edited the Strachey-Brooke correspondence, which was finally published in 1998, says that Keynes’s editor at Faber wrote again and again in the margins of the copy: ‘Why delete?’, ‘Why bowdlerise this?’) The collection had been slated for publication a decade earlier, but Dudley Ward, one of the other trustees, complained that even Keynes’s version was insufficiently sanitised. Christopher Hassall was asked to write the authorised biography in part because, as Nigel Jones notes in his own biography of Brooke, Hassall’s lengthy Life of Eddie Marsh had managed ‘to avoid the topic of his subject’s homosexuality’ and he could therefore be relied on to be discreet. (It’s unfair to say that Hassall doesn’t tell the truth about Brooke, but he muffles it, burying it under piles of detail.)

Expurgation wasn’t good for Brooke or for his reputation, but its opposite has been differently damaging. Marsh’s memoir told its story largely through the letters Brooke sent; the new version of Brooke also has its origin in letters which have emerged from private collections, like those to Strachey or Noel Olivier, or from under time-seals, like those to Phyllis Gardner, but these ones seem to show a man who was ‘jealous, moody, ill-balanced’, as Woolf had said, and who renounced the unconventionality of his youth to revert to philistine type: ‘the Rugby ethos’, as Paul Delany calls it, ‘that not only was character more important than brains but that brains, in themselves, were objects of suspicion’. Both versions are too fixed, and it’s easy to feel that Brooke’s faults are now being overstated. He’s a ‘cynical and heartless philanderer, with a streak of childish cruelty’ according to Jones; Delany pathologises his relationships with women (‘marriage itself, with anyone … was beyond reach for him’) but not his nervous breakdown. Delany complains that Hassall and Keynes suppressed the letters’ most vitriolic attacks and hints that he believes the ‘nasty parts show the “real” Rupert, the golden boy with the rotten core’.

Delany first wrote about Brooke in 1987 in The Neo-Pagans, a collective biography of Brooke and some of his friends, who earned their nickname, first used by Woolf, from their fondness for bathing and camping and their worship of youth and friendship.* He writes in the introduction to his new book that ‘over such a span’ of years ‘times will change, and authors will change with them.’ But not much: the tone remains the same and so does the vast majority of the content, juggled around a bit, but essentially unaltered. In 1906 Brooke went to Cambridge from Rugby where, despite what one might have imagined as the awkwardness of his father being a housemaster, he had been ‘happier … than I can find words to say’. One of the first people he met at Cambridge was Justin Brooke, son of the grocer who founded Brooke Bond tea, who roped Rupert into appearing as the Herald in Aeschylus’ Eumenides. All he had to do was look pretty and pretend to blow a trumpet. It was the first time Marsh saw his ‘radiant, youthful figure in gold and vivid red and blue … after 11 years the impression has not faded.’ The sight made Strachey declare himself: ‘I must just write to tell you (a truism) that you were very beautiful tonight. How sorry I shall be tomorrow morning that I sent you this! How angry you will be when you read it! Vogue la galère.’ Brooke was ‘irritated’, but Strachey continued to spend ‘his time dreaming of Rupert over a solitary fire’, as his older brother Lytton wrote, and trying to convince Lytton and Maynard Keynes to elect him to the Apostles. Neither of them could see what their younger brothers saw in Brooke – at least, they appreciated the good looks while being unsettled by the devotion he aroused – but in the end they capitulated. Brooke was perfectly aware of the reason for his election, but he didn’t mind; he was used to male admiration and to batting it away (or not). He enjoyed the secrecy and the exclusivity of the Apostles and, like the eponymous hero of Jacob’s Room, who is partly based on him, he was still more at ease with ‘male society, cloistered rooms, and the works of the classics’.

He also joined the Fabians, encouraged by Hugh Dalton, the postwar Labour chancellor. He took it seriously, did a lot of reading, especially about the Webbs’ Minority Report on Poor Law reform, and in the summer of 1910, at the end of his year as president of the Cambridge society, he and Dudley Ward toured the West Country in a caravan, speaking on the subject on village greens. Beatrice Webb, however, was one of the few not to fall for Brooke’s charms. ‘There was a remarkable scene,’ Strachey wrote of one Fabian Summer School, ‘in which Rupert and I tried to explain [the philosopher G.E.] Moore’s ideas to Mrs Webb while she tried to convince us of the efficacy of prayer.’ ‘They don’t want to learn, they don’t think they have anything to learn,’ Webb wrote. ‘The egoism of the young university man is colossal.’

Both the Fabians and the Marlowe Dramatic Society, which the two Brookes founded, admitted members from the women’s colleges; most of those who would be counted as Neo-Pagans came from one of these groups. Several, like Justin Brooke, had been pupils at Bedales, which, progressive and co-educational, keen on camping and acting, represented an attempt to break away from the public school ethos encapsulated by Rugby. The group had its own rules, which Brooke recapitulated to Katherine Cox, whom he met when she was treasurer of the Fabians, and with whom he would have an affair that broke these rules. She hadn’t been sure whether she should let Geoffrey Keynes buy a portrait of her by Duncan Grant: ‘We don’t copulate without marriage,’ he wrote, ‘but we do meet in cafés, talk on buses, go on unchaperoned walks, stay with each other, give each other books, without marriage. Can’t we even have each other’s pictures?’ But the practice of comradely chastity was hard to sustain. Couples formed, and worries about sex, marriage and marriageability increasingly constrained the behaviour of the Neo-Pagan women, as they did that of the still unmarried Virginia Stephen. She felt excluded by the sexual exploits of the homosexual men around her – pretty much all of them Apostles – even while she felt exhilarated by the lack of inhibition in their discussion of them. Despite their illegality, what she called ‘the love affairs of buggers’ seemed less problematic than heterosexual relations. For one thing, their sexual choices weren’t final, while Stephen and the Neo-Pagan women – and most of the men – felt theirs were. Premarital sex had consequences – pregnancy, loss of reputation – that most of these sensible, well-educated women weren’t prepared to risk.

The first woman Brooke fell in love with was one who was going to remain out of reach for some time. In May 1908 he went to a Fabian supper party to which some grand guests had been invited, including the governor of Jamaica, Sir Sydney Olivier, who brought three of his four beautiful daughters (Laurence Olivier was their younger cousin). He already knew two of the sisters but now he met the youngest, 15-year-old Noel – he helped her pick up the fragments of the small green coffee cup she’d dropped. He would spend the next two years hatching schemes that would allow them to meet, most of them thwarted, by the fact that she was still at Bedales, by her protective older sisters, or by Noel herself, who held him at arm’s length, accepting, as Brooke’s friend Jacques Raverat put it, ‘his devotion with a calm, indifferent, detached air, as if it were something quite natural’. In the summer of 1910 Olivier agreed to become engaged to Brooke, but she wanted to keep it secret, and it didn’t make her more available. Her untouchable quality infuriated him and appealed to him; Olivier herself parsed it as ‘beastly indifference’. ‘You seem to want us to be in love so much; why do you?’ she asked him.

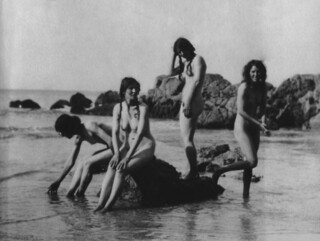

He’d gone to live in the village of Grantchester in 1909 after getting a second in his Tripos and agreeing with his tutors that he would switch from Classics to English and move out of Cambridge in order to concentrate on his work, with the aim ultimately of winning a fellowship at King’s. He did work, interrupted by hordes of visitors who came to admire his new embrace of the simple life: he’d given up meat, tobacco and alcohol, and as Raverat wrote, dressed ‘in a dishevelled style that showed off his beauty very effectively’. One of his visitors was Virginia Stephen, trying out ‘youth, sunshine, nature … cakes with sugar on the top, love, lust, paganism’. She helped correct the proofs of his first collection of poems and went swimming with him ‘quite naked’ – this was another borrowing from Bedales, thought by its headmaster to promote ‘mental as well as … bodily health’, except in those it made ‘unwholesomely sex-conscious’. (Woolf would later tell people that Lytton Strachey was wrong to say that Brooke had ‘bandy legs’; in Michael Holroyd’s biography James sides with his brother: ‘Rupert had bandy legs, all the same.’) This was, as Delany writes, the high summer of Neo-Paganism: Brooke read Paradise Lost to his admirers high in a chestnut tree; canoed down the river at night, stopping without fail at the sound of the poplar rustling at the bottom of the garden; swam in Byron’s Pool where the water smelled of wild peppermint and mud.

Soon after he arrived in Grantchester he’d taken advantage of the relative privacy to seduce Denham Russell-Smith, the younger brother of a schoolfriend, in what he later told Strachey was a deliberate attempt to ‘do away with the shame (as I was taught it was) of being a virgin. At length, I thought, I shall know something of all that James and Norton and Maynard and Lytton know and hold over me.’ This letter (written in 1912 just after he’d been told that Russell-Smith had died of septicaemia) gives a very detailed account of their encounter, and must have been one of those Geoffrey Keynes was most keen to suppress. When Brooke went to Munich at the start of 1911, to study philology, he made an attempt to get rid of his heterosexual virginity and asked Strachey to find out about methods of contraception. James obediently explained the ‘whole sordid business’, complete with illustrations – although he did add: ‘Come quietly to bed with me instead’ – but the woman involved, Elisabeth van Rysselberghe, seems to have declined to sleep with Brooke on these terms (he asked for her letters to be destroyed after his death). He was outraged. ‘I can’t help believing (am I right?),’ he wrote to her, ‘that if we’d met in Venice, that there, touching your hands, looking into your eyes, I could have made you understand, and agree.’ Later, it seems, she did agree.

Olivier moved to London in the autumn of 1911 to study medicine and was bombarded with demands from Brooke to go to the Ballets Russes, to Wagner, to tea. But in December they decided to stop seeing each other. It seems to have been Brooke who ‘couldn’t face’ going on as they were. Olivier tried to reel him back: ‘Perhaps you forgot to feel that the scarce moments (when I rejoiced in you) did make our strange and jerky life worthwhile.’ But he replied: ‘I’d only go back to a Noel who barely wanted to see me.’ Delany believes that Olivier, ‘so clear and firm by nature’ (‘unemotional and stony’ was the way Brooke put it), had helped keep his ‘tendency to sexual hysteria’ in check. It is equally possible that her disdain for emotions ‘that destroy all one’s judgment and turn one into an ape’ made him more likely to despise any woman who admitted to them as well as himself for being subject to them.

He had been trying to finish his fellowship dissertation on ‘John Webster and the Elizabethan Drama’ (he did win a fellowship, but not until 1913). He wasn’t sleeping; Olivier said he seemed ‘dotty & queer’, liable to say or think ‘horrors’. He didn’t even pay all that much attention to the publication of his first collection, Poems 1911, which was well reviewed despite the supposedly excessive realism of some of the poems (one was about sea-sickness, another about a lover’s ‘smell’) and the over-supply of Decadent juvenilia. He’d also got involved with another woman. Ka Cox must have seemed more likely to respond to him, even if she’d turned down Raverat a few months before (‘You’re too much of a baby,’ she’d said). Raverat had wasted little time before getting engaged instead to Gwen Darwin and both Cox and Brooke were disturbed by the pairing off of their friends. Brooke, he told Cox, felt ‘the ignoblest jealousy mixed with loneliness’. Stephen too envied them: ‘For some reason that turned more of a knife in me than anything has ever done,’ she wrote to Gwen Raverat in 1925, after Jacques’s death from multiple sclerosis.

Cox didn’t have the obvious good looks of the Olivier sisters, but she seems to have had many admirers. She had an individual style: she made her own clothes (and many of Brooke’s shirts; Yeats, as well as saying he was the handsomest young man in England, had added that he wore the most beautiful shirts). Gwen Raverat remembered her ‘standing on the very edge of the cliff, her crimson skirt whirling in the wind, her head tied up in a blue handkerchief, and the gulls screaming below’. She was also soothing and sympathetic: ‘Why do you invite responsibilities?’ Brooke asked her. ‘Are you a cushion, or a floor?’ He’d been spending the time Olivier wouldn’t spend with him with her. But she wouldn’t go to bed with him either: ‘I’d baby ideas about “honour”,’ he wrote, ‘“giving you a fair choice” “not being underhand” “men (!) and women (!) being equal” – – – I wanted you to fuck. You wouldn’t, “didn’t like preventives” … I was getting ill and stupid … I threw all my affairs – all the mess Noel and I had made – onto you.’

He wrote this after the breakdown that would soon follow, and which is often ascribed, as it is by Delany and Jones, to the rapprochement between the Neo-Pagans and Bloomsbury being ‘deeply threatening’ to Brooke’s ‘divided and compulsively secretive nature’. The evidence that he had kept his friends apart and that disaster followed inevitably when these two incompatible groups met is rather shaky. Brooke had what sounds like a bipolar episode triggered by overwork, stress and romantic unhappiness. It wasn’t really anything to do with Bloomsbury even if he afterwards told himself that they’d been plotting against him. He had asked Cox to organise a New Year’s house party at Lulworth in Dorset. At the time, Lytton Strachey was obsessed with the heterosexual painter and philanderer Henry Lamb, whom Cox had recently met and fallen for. She asked Lytton to invite Lamb, and he happily obliged. Lamb was looking for a new mistress and Cox was well-off, generous and susceptible. The match would have suited Lytton (rather like the triangular relationship, a few years later, with Carrington and Ralph Partridge). When Lamb arrived, he and Cox disappeared for a few hours; the next morning she told Brooke she was in love with Lamb and hoped to marry him – he was older than Brooke, she said, and had the same first name as her dead father. Brooke begged her to marry him instead and tried to get her to promise never to see Lamb again. He felt humiliated by ‘someone more capable of getting hold of women … who didn’t fool about with ideas of trust or “fair treatment”’. Finding all this rather more than he’d bargained for, Lamb disappeared back to London, where Lytton wrote to update him: ‘Rupert is besieging her – I gather with tears and desperation – and sinking down in the intervals pale and shattered … I never saw anyone so different from you – in caractère. “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” I sometimes want to murmur to him. But I fear the jest would not be well received’ (Delany stops the quote at ‘shattered’).

Brooke was taken to London by the Raverats to see Dr Maurice Craig, who also treated Woolf, and was given much the same diagnosis: ‘severe mental breakdown’, to be treated by complete rest and ‘stuffing’ (‘I have to eat as much as I can get down, with all sorts of extra patent foods and pills, milk and stout’). His mother was spending the winter in Cannes and he was sent to join her. From there he wrote feverishly to Cox, protesting that all would be well when she met him, as she’d promised to do: ‘you go burning through every vein and inch of me, till I’m all Ka … I’m certainer than ever that I’m, possibly, opening new Heavens, like a boy sliding open the door into a big room; trembling between wonder and certainty.’

When she did meet him she eventually summoned up the courage to admit, on the station platform in Munich, that she was still in love with Lamb. This time Brooke didn’t propose marriage but sex. Cox seems – although it’s hard to say for sure – to have got pregnant and then miscarried, although this too is far from clear (her letters were also destroyed after his death). Her feelings for Lamb soon began to cool, but so did Brooke’s for her: ‘Ka’s done the most evil things in the world. She has … dirtied good & honour & all high things, & betrayed & degraded love … I’d not care if I saw Ka dying of some torture I could inflict on her, slowly.’ He wrote a lot of letters like this one, full of ravings about ‘cleanness’ and ‘dirt’ and ‘filth’ (this language reappears in his first war sonnet). By sleeping with him when she was in love with Lamb, she merely showed how easily women were corrupted. Now that she was willing to marry him, he no longer wanted her. It was around now, in Germany for a second, unhappy meeting with Cox, that Brooke wrote ‘The Old Vicarage, Grantchester’. He hadn’t been there since his breakdown and the longing for the world before the fall is clear in the description of the Cam, site of his apotheosis, where the chestnuts make

a tunnel of green gloom and sleep

Deeply above; and green and deep

The stream mysteriously glides beneath,

Green as a dream and deep as death.

He could still write fluent Marvellian octosyllables, but he was a wreck. He blamed Lytton for his plight, for acting as Lamb’s pimp: ‘it was the filthiest filthiest part of the most unbearably sickening disgusting blinding nightmare – and then one shrieks with the unceasing pain that it was true.’ His fury didn’t diminish after he began to recover; in fact his paranoid delusions were now aimed more widely at the groups he saw as responsible for his humiliation. Women were attacked, especially ‘feminists’, as were Jews (the Stracheys were described as ‘pseudo-Jews’), homosexuals and ‘intellectuals’ – all his friends, in essence.

He decided he was in love with the uncorrupted Noel Olivier again, and sent histrionic rambling letters warning her against Bloomsbury – ‘They’re mostly very amusing people as acquaintances, but not worth making one’s friends because they’re treacherous & wicked’ – and demanding that she marry him. Meanwhile, he flirted with her sister Bryn, described by David Garnett as ‘the most beautiful young woman I have ever known … with … starry eyes that flashed and sparkled as no other woman’s have ever done’ (Woolf imagined her taking out an eye and polishing it till it was shiny). He was wretched when Bryn told him she was engaged. His pleas to both sisters, accompanied by threats of suicide (‘I think a great deal and very eagerly of killing myself’), were kindly but firmly rebuffed. In the autumn, calmer now, he wrote to Noel sadly that ‘one is like a child, in the important little way one trots around with one’s dreams.’

James Strachey had put up stoically with Brooke’s rants and kept him company (he couldn’t bear to be alone): ‘You’ll find food on the table & me on my last legs … God damn you. God damn everyone. God burn roast castrate bugger & tear the bowels out of everyone … You’d better give it up; wash your bloody hands. I’m not sane.’ He was, he admitted, ‘very fond’ of James, but the supposed contagion of Stracheydom in the end trumped that: ‘To be a Strachey is to be blind … towards good & bad, & clean & dirty; irrelevantly clever about a few things, dangerously infantile about many; … to be a mere bugger.’ James thought the reason for Brooke’s anger was that he had now fallen in love with Olivier: ‘the explosion … has had every motive assigned to it except the obvious one.’ Brooke certainly hated being lumped with James and Woolf’s brother, Adrian, ‘into the class of your rejected suitors’, though he’d have hated it more if Strachey had succeeded.† ‘My deadly slight affection for him is the most distressing thing (I hear you managed better by being snappy),’ Olivier wrote to Brooke in 1913. Strachey was persistent, as Brooke knew, but even he eventually gave up. ‘Noel, for James, as for Adrian, the unattainable romance, though she has married Jones or Richards, & is romantic no more,’ Woolf wrote in her diary in 1921, soon after Strachey married. In 1932 Olivier and Strachey finally began an affair that would last a decade.

While the existence of Brooke’s correspondences with Olivier and Strachey was known – it was just that they couldn’t be read – another set of letters that no one since Marsh seems to have known about emerged in 2000, when a brown paper parcel given to the British Library in 1948 with a fifty-year time seal was opened. It contained a bundle of letters and a memoir with ‘A TRUE STORY’ typed on the title page. Phyllis Gardner first saw Brooke when her mother pointed him out in the refreshment room at King’s Cross in November 1911. They travelled to Cambridge in the same compartment and she spent the journey sketching him (she was a student at the Slade). The next day Olivier helped her identify the figure in the drawing. In January 1912, when he was in Cannes with his mother, Brooke wrote to Cox about Gardner:

You know about the Romance of my Life. I know I told you, because I remember how beastly you were about her – Miss Phyllis (is it Phyllis?) Gardner. Everyone was so beastly that I hadn’t the heart to meet her. She went to tea day after day in St John’s Wood [where the Oliviers were living], and I was always too sulky and too schuchtern to go … Oh, I’ve put it in the hands of my solicitor (Miss Noel Olivier) who has been acting for me in this matter throughout.

He added that he’d heard from ‘an elderly woman’ who’d bought Poems 1911, and ‘thought it all frightfully good (particulars)’ and wanted to meet him. This was Gardner’s mother, who was, or wanted to be, a collector of literary young men (‘These Gardners are the kind that hunt lions,’ Robert Frost, her next target, said). She was acting for her daughter in this matter. Months later, Brooke offered to have lunch with Mrs Gardner. Phyllis went too and was entranced, ‘carried along on a kind of irresistible current’. She knew nothing of his breakdown or his entanglements; as she makes clear in the artless memoir written in 1918 and printed along with their letters and a commentary by Lorna Beckett in The Second I Saw You, she saw only his beauty and his charm.

She went to visit him in Grantchester just after what seems from his letters and his behaviour to have been his most disturbed period and, though it was October, ended up naked in the river with him, where the ‘water was black and cold’. ‘We agreed,’ she writes, ‘that having nothing on was a very desirable and enviable condition.’ ‘Aren’t you afraid?’ he asked her. ‘One’s so primitive.’ Perhaps she should have been, because he put his hands round her neck and said: ‘“Supposing I were to kill you?” And I smiled up at him and said: – “Supposing you did? Then I should be dead” … I was in a sort of heaven, although once he made me choke.’ Afterwards he wrote to her, ‘Did you know what you were saying, child, when you said “Why shouldn’t we be primitive, now?” God, it was a hard struggle in me, half against half, not to be.’ Gardner didn’t answer this question, probably because she didn’t realise what he was suggesting. Soon, he made it clearer. ‘I must have you, here,’ he said to her, ‘laying a hand over what is delicately referred to by artists as “the central point of the figure”’. She imagined herself ‘the happy mother of his child’, but a day or two later, having greeted her by telling her that ‘All women are beasts! And they want a vote – but they’ll never get it,’ he gave her the talk about contraception: ‘“There are ways – ” My heart sank within me. Where was my castle in the air, where my visionary child?’ She wrote him a very morally correct letter, telling him that no ‘female who isn’t a beast can consent … practically [to] the murder of her offspring’. Of course what upset her most was that, as she rather bravely told him, he didn’t ‘want me enough to do so much as consider the possibility of marrying me’. His reply implicitly admitted this, telling her that he was a ‘wanderer’, taking ‘what one wants where one finds it, to be friends here, lovers there, married there, to spend a day with some, a week with others, – possibly a lifetime with others’. But not with Phyllis. She in her turn had a breakdown and ‘by the time I had recovered a little I heard he had gone off to the South Seas.’ He’d had a vague plan to go to California for months, but Gardner’s mother’s furious letters combined with a commission from the Westminster Gazette for a series of travel articles on the US and Canada made up his mind. ‘I’ve got to go, for a bit,’ he told his newest girlfriend, the actress Cathleen Nesbitt. ‘Because I promised. I got mixed up with a woman.’ ‘I am sorry it has all been like this; and that you think me disgusting,’ he wrote to Mrs Gardner before he left.

Brooke wrote to Phyllis a couple of times during the year he was away, first in North America then in the South Sea islands. She claimed to have seen evidence of a return to ‘sanity and naturalness. I felt in a way that my violent silly protest against his whole attitude had not been wasted.’ She might not have felt the same if she’d known what he was up to: an ‘Episode with a Widow’, as he described it to Marsh, in Canada and affairs with, Delany believes, two women in Tahiti (he claims that most of Brooke’s biographers have conflated two different women). ‘I think I’ve been doing too much fucking,’ he wrote to Marsh. ‘Shaw says it’s bad for one’s work. Do you think that’s true?’ He wrote some of his best poems there. One of them, ‘Tiare Tahiti’ rejects Platonic ideal forms – ‘you’ll no longer swing and sway/Divinely down the scented shade,/Where feet to Ambulation fade/And moons are lost in endless day’ – for human pleasures ‘this side of Paradise’. Coy mistresses in Tahiti were easier to persuade.

He returned to London two months before war broke out. Soon afterwards he met Lytton Strachey at the Russian Ballet and turned on his heel. He wrote James a note – after what James described as an ‘apparently very friendly evening at the Hippodrome’ – telling him that his opinions, on the war presumably, were ‘not only eunuch and shocking, but also damned silly & slightly dangerous’. He also bumped into Noel Olivier at the theatre: ‘I met her the other day & didn’t recognise her for some minutes. That was a triumph … I went home & laughed about it for an hour.’ He kept Cox at a distance: ‘the thought of you – at least if it’s made vivid by your presence – makes me feel deeply and bitterly ashamed of myself.’ Gardner saw him twice more, for tea, both times with her mother in attendance.

She had felt sure he would be killed: ‘I knew that he had come to his full strength, that all his wrongnesses and foolishnesses were wiped out, and that he had therefore fulfilled his appointed task in life.’ After his death her mother wrote to Marsh, attaching a poem that ends: ‘Too brief the song, too swift the sight/Before thy angel took his flight.’ For Mrs Gardner, the myth of the noble soldier-poet helpfully obliterated all traces of the less than perfect man. Olivier, sentimental at last, told Strachey that now she would never marry for love. Strachey himself claimed he’d ‘cried a lot more … when he went off in 1912’; Lytton, however, told Duncan Grant that ‘James is a good deal shattered’ – again, letters don’t tell us a single truth. Only Cox got a farewell letter: ‘I suppose you’re about the best I can do in the way of a widow,’ it began.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.