David Solkin ’s new book is designed to replace Painting in Britain 1530-1790, a volume of the Pelican history of art by Ellis Waterhouse, which was first published in 1953 and appeared in five separate editions, the last in 1994, nine years after Waterhouse’s death. Waterhouse’s history was quickly recognised as a classic. To a large extent he made the subject he was studying; or as Solkin puts it, ‘he revealed a verdant topography where previous observers had perceived a barren wilderness.’ He found numerous hitherto unknown works and little-known artists, and was able to do this by virtue of ‘a breadth of experience which he alone possessed, after many years of scrutinising pictures in private collections and the sale rooms, and of collecting information from catalogues, archives and primary texts. His outstanding achievement was to forge those fragmentary materials into a magisterial survey that illuminated countless pathways for others to explore.’

I came late to Painting in Britain; when I eventually read it many of those pathways had begun to be explored and I didn’t recognise Waterhouse’s book as the pathbreaking achievement others knew it to be. Looking at the marginal marks in my copy, I see that I too quickly decided it was one of those genteel compilations typical of the history of British art in the decades after the Second World War. I was particularly struck by Waterhouse’s concern with the pedigrees of the painters he discussed, men like Thomas Jones, Richard Wilson and Sawrey Gilpin, all of whom are adjudged to be of ‘good family’, and Sir James Thornhill, who came from ‘good Dorset stock’, a phrase more at home in a book on country cooking than in a serious work of scholarship. Why pedigree mattered to him is rarely clear, as by his own account it seems to have no particular influence on the nature or quality of an artist’s work. There were some exceptions: Thomas Hill was ‘something more like an English gentleman than most contemporary portrait painters’, and accordingly one of his works is remarkable for its ‘gentleness and refinement’. On the other hand, the fact that so many portraits by John Opie ‘are thoroughly dull, if not frankly bad’, was owed to the fact that as the son of a carpenter ‘he had no elegance in his make-up, but was commissioned to do portraits of fashionable persons.’

Remarkable for its range as Waterhouse’s book was, it remained as Solkin describes it, a ‘survey’, more a catalogue than a history. The whole Pelican project, Solkin argues, was based on a series of assumptions that no longer command much credit: the notion that, ‘as a repository of timeless human values, art should be understood as occupying a world unto itself, a realm that transcends the historical circumstances of its creation’; the belief that histories of art should treat ‘matters of quality, attribution and dating’ as the most important questions; that they should consist of a ‘parade of individual “great” male artists or canonical masterpieces’. There can be no room in such a project for artists such as Anthony Devis, adjudged by Waterhouse to be ‘an altogether minor person’; or those whom it is ‘sufficient to mention’ but unnecessary to discuss; or the numerous and nameless ‘journeymen hacks’ who ‘cannot find a place in a general history of British painting’.

Solkin is the author of two or three of the most important books on 18th and early 19th-century British art to have been published in the last quarter-century, including Painting for Money (1993) and Painting out of the Ordinary (2008). In his Pelican history he has attempted something even more ambitious, and has been triumphantly successful. He describes it as a ‘social history of art’, a critical analysis of how the visual culture of the 18th century ‘operated within a social field structured by relationships of power’. The book is extraordinarily comprehensive, its discussion of the different genres of painting as they develop through the 18th century so full, detailed and thoughtful that it will be completely impossible to do it justice even in the generous word count permitted by the LRB.

Solkin treats the history of 18th-century British art as a braid of ‘intertwining narratives’, a series of transactions between opposite, sometimes conflicting qualities, characteristics and influences, associated with the cultures of different social classes and national schools. Though aristocratic culture, Solkin argues, continued to command ‘unsurpassed authority’ in Britain throughout the 18th century, it could not help imbibing the values associated with trade, with the middling classes, or with the ‘exhibition public’, of which more later. In the early 18th century, the more the English/British realised that they were, or were about to become, one of the great military and commercial powers of Europe, the more evident and embarrassing it became that as a cultural power England/Britain ranked far below Italy and France. To some the literature of Britain was doomed to remain second-rate, for how could anything worthwhile be written in the barbarous, ungrammatical language of England, where verbs did not conjugate, nouns decline or adjectives agree? The visual arts laboured under no such handicap, but still artists and patrons, like writers and critics, were divided about what the arts in Britain should be like. Should they be modelled on those of Greece and Rome, France and Italy, and aspire to transcend national character and become, as those cultures were supposed to be, transnational, universal? Or should English or British culture emphasise its Englishness, its Britishness, and along with it the Protestantism and the passion for liberty which were believed to distinguish England from France in particular? If there is any clear outcome by 1815, when Solkin’s history ends, it is that by the time Britain has overcome the French Empire, at Trafalgar and then at Waterloo, it has also overcome its cultural cringe, its posture of humility towards the culture of continental Europe.

In the reigns of the last two Stuart kings, there was little if any expectation of a native English School emerging, and almost all high-end paintings were done by foreigners, either immigrants in search of patronage or sent for especially to produce works supposed to be beyond the competence of native artists. In his ‘Essay towards an English School of Painters’ (1706), however, Bainbridge Buckeridge made a special effort to record as many painters as possible who he could claim ‘belong’ to us, or that were ‘ours’. Under the letter ‘V’ he lists Henry Vanderborcht, John Vander-heydon, Adrian Van-Diest, Sir Anthony Vandyck, William Vander-velde, Francis Vanzoon, Herman Verelst and F. de Vorsterman, and with a little more diligence he could easily have doubled this collection of foreign Englishmen. Of the 106 painters accorded a biographical sketch by Buckeridge, 55 were immigrants or visitors to England. The leading portrait-painters in the period from the Restoration to the Hanoverian accession included the Frenchman Henry Gascar, the Flamand Jacob Huysmans, the Dutchman Gerard Soest and the Schleswiger Godfrey Kneller. Topographical and landscape artists were led by Wenceslaus Hollar, Henrick Danckerts, Adrian Van-Diest, Jan Siberechts and so on. Faithful to this notion of an English School of Painters, the opening chapters of Solkin’s book (Art in Britain, not British Art) contain discussions of far more foreign painters than of artists native to the British Isles.

By the turn of the 18th century, Solkin writes, ‘the most prestigious and authoritative pictorial language for the celebration of power’ was allegorical painting, often on a huge scale, covering the walls and ceilings of great halls, in decorative schemes celebrating royalty, the aristocracy or the state. Until James Thornhill began decorating the lower and upper halls at Greenwich Naval Hospital, such schemes were generally entrusted to painters from Italy or France, notably Antonio Verrio, Louis Laguerre and the Huguenot Louis Chéron. They often depicted stories of the Olympian deities, and didn’t necessarily refer directly to those whose power they celebrated; but their scale, the months or years they took to complete, and their obvious expense were enough to demonstrate the status of those who commissioned them. In a particularly illuminating comparison, Solkin discusses the differing treatment by Verrio and Chéron of the story of Mars and Venus, caught by Vulcan in flagrante. In Verrio’s version for the Earl of Exeter at Burghley House the entwined, naked pair are fast asleep, unaware of having been discovered not only by Venus’ husband but by a large and fascinated audience of heavenly beings painted on the ceiling and along the walls. In Chéron’s version, for the state bedroom intended by the Duke of Montagu to accommodate William III when he visited Boughton House in 1695, the lovers are awake, and Venus is shown turning away from Mars and Vulcan, attempting to cover her face with her arm. The Olympians in the sky above her seem quite unconcerned at her adultery: it is from us, and perhaps in particular from William, that she seeks to hide her shame.

The duke, Solkin suggests, ‘must have been aware of William III’s concerted efforts to purge the monarchy of the taint of libertinism left behind by Charles II’, and so he may well have designed the room ‘with this reformist agenda in mind’. That William would have found Venus ashamed less rather than more exciting than Venus asleep is questionable, but she was at least acknowledging that her behaviour did raise moral issues, which the portraits of ‘beauties’ favoured in good King Charles’s golden days, with heavy-lidded, bedroom eyes and low, loose necklines – whether out-and-out courtesans or women of almost unblemished reputation – did not. By William’s reign it began to be fashionable for women to be painted as the mothers of children, but still with something of the look of a court ‘beauty’, as Sarah Churchill appears in John Closterman’s group portrait of the Marlborough family at Blenheim: an aristocratic lady with an authority that comes in part from her willingness to adopt something of the more responsible values of the middling class.

Once the Stuarts are dispatched, the story of art that Solkin tells, for the early 18th century, is the story of the relation between art imagined as directed at the landed aristocracy, at men of public virtue, whose interests coincided with those of the public, and the ‘land’ in the sense of the nation, apparently in opposition to a growing commercial class of men supposed to be motivated by their own desires and interests, but whose fortunes, invested in trade and industry often via the stock exchange, were the means of enriching the nation as well as themselves. At the same time, as Solkin points out, it wasn’t quite like that. As early as 1700 landscape paintings – his most telling examples are by Jan Siberechts – may depict ‘a verdant territory’ given over to both ‘ornament and agriculture’, to pastoral and georgic, to places of leisure and places of work, such as cabbage fields and bleaching grounds. The presence of such mundane details, he argues, ‘attests to the willingness of Britain’s landed gentry to fashion a mixed identity for themselves, as the culturally enlightened members of a leisured ruling class on the one hand, and as the pragmatically minded overseers of Britain’s productive acreage on the other’, keen to promote the idea that ‘private wealth played a key role in establishing a harmonious balance between nature and society.’ Something similar but opposite is true also of the primarily moneyed interest, insofar as they manage to become participants in the landed interest also. A wonderful landscape of Henley from the Wargrave Road is one of a number of paintings Siberechts produced for rich City businessmen who had bought productive Thames-side estates near Henley. It shows the river made navigable for barges, carrying not only agricultural produce but rags and other recyclable waste, through a rich landscape of cornfields, meadows, pasture and woodland.

The converging values and interests of the landed and the mercantile elites did not obscure the social and cultural differences between them. But those differences could be reconciled, it was suggested, by ‘politeness’, a form of refined sociability that could be practised or performed by ‘those educated men and women of property who could justifiably describe themselves as gentlemen and ladies’. Politeness was principally acquired by social commerce, by conversation, and the ‘amicable collisions’ it occasioned, which smoothed the rough sides of characters and behaviour.

The idea of politeness as the glue of society, at least of its landed and commercial elites, found visual expression in two kinds of portraiture. One was invented by Godfrey Kneller to depict his fellow members of the Kit-Cat Club, the Whig society which Solkin describes as devoted to promoting ‘the social, cultural and commercial values they identified with politeness’, and to ‘building a new economic order which cemented a mutually beneficial alliance between the court and the monied interests in the City’. These portraits were painted to be hung together in the regular clubroom, in the house of the publisher Jacob Tonson.* ‘Kit-Cats’, as these and similar portraits came to be known, were smallish pictures, showing the top half of the sitter only, close up to the spectator, as if to bring the two into a more intimate, confidential and potentially conversational relationship than portraits normally did. The poses and expressions of the club members, both aristocrats and commoners, were remarkably similar; all wore ‘the bewigged mask of the well-bred man’, as if to demonstrate their shared values and to ‘support the Kit-Cat Club’s commitment to forging a cultural consensus uniting different elements of the propertied classes’. Most were shown with the head ‘turned just a touch to one side’, with a ‘slight incline of the upper body’, and ‘one arm bent at the elbow’, supported by a handy piece of furniture. It seems as if everything but the face could have been painted before the subject sat for the artist, in a way reminiscent of the cut-out boards on seaside piers, or indeed at the Yorkshire branch of the National Portrait Gallery at Beningbrough, which we are invited to stand behind, grinning or girning through a face-shaped hole. In the Kit-Cat portraits, however, as Solkin points out, ‘all the faces suggest the same even and unruffled temper, a complete command of self coupled with a sociable ease in the presence of others’; and while certain gestures may suggest the sitters are about to speak, as a rule they appear ‘more inclined to listen’.

The sitters almost never seem to speak, either, in the other genre of portraiture particularly intended to represent and encourage politeness: conversation pieces. These were a development from Dutch ‘drolls’, pictures of groups of peasants, often carousing in pubs, often already drunk, but in Britain they characteristically portrayed groups of men on homosocial occasions, or families of the aristocracy or the more well-off middle classes, sometimes along with a few select friends. They pose together, supposedly informally, to show off their good breeding and good taste, but how successful they are, as models of civilised conversation, is debatable. Though they sometimes exchange looks and glances, for the most part the men look past each other, and seem to have taken a vow of silence. What inhibits them from speaking isn’t clear. It may have been the familiar 18th-century anxiety about the mismatch between the representation of bodily activity, by nature diachronic, and the synchronic nature of the visual arts. This issue, chewed over by so many late 18th-century theorists of the visual arts, from Lessing to Fuseli, was always discussed in relation to the rapidly transient expressions of extreme emotion – extreme pain, extreme grief – which, it was argued, come to look merely grotesque when frozen in a still image. But if this were true, the same would apply to the transient but not at all extreme expressions of those engaged in convivial conversation, as arguably becomes apparent in caricatures. The strangeness of some 18th-century conversation pieces comes in part from the juxtaposition of portraits of individuals in social situations in which they do not seem able to participate easily. An intriguing case in point is Gawen Hamilton’s A Conversation of Virtuosis at the Kings Armes, in which more than a dozen men, all but one of them professional artists, sit or stand together in an extended frieze and seem to take almost no interest in one another.

A second reason for these strange and awkward silences may be that polite conversation, far from being the relaxed and informal activity it was supposed to be, was for many people, especially for those not born to it, apparently a trial by ordeal, or associated, at the least, more with anxiety than with ease. As dozens of 18th-century publications made clear, polite conversation was governed by a host of protocols, rules and prohibitions that must have been more likely to inhibit than facilitate the activity; and this may have been the case too for artists trying to represent it. For them, many of them foreigners and strangers to British polite culture, some of them on the wrong side of the polite/vulgar divide, the fear of flouting the rules in representations of polite conversation may well have been as inhibiting as it was for their subjects.

Perhaps also patrons and artists were wary of appearing too polite when to be so may have made them seem too French. Frenchness, as Solkin writes, ‘had long been synonymous with fashionability, allied with connotations of foppishness and luxurious effeminacy’, and luxury, itself nearly synonymous with effeminacy, was the great enemy of public virtue. In the 1730s and 1740s the great satirist of Frenchness was Hogarth, in The Gate of Calais for example (though here it was not French fashion he was laughing at, but French poverty), in A Rake’s Progress and still more in Marriage A-la-Mode, the narrative of a marriage which collapses under the weight of the partners’ attempts to be fashionably French in their behaviour. Hogarth’s magnificent portrait of Thomas Coram, the founder of the Foundling Hospital, is the very image of militant, consciously unsophisticated Englishness, in his ‘ruddy complexion’ and ‘rough-hewn features’ as well as in his refusal to wear a wig, preferring to display the great shock of his own white hair. Hogarth’s technique in the portrait, Solkin points out, was as ‘distinctively English’ as Coram himself: its ‘palpable facture … positively calls attention to its lack of Continental polish’.

That polish, however, would soon be more sought after in Britain. The brief sojourns of the French portrait painters Jean-Baptiste Van Loo and Jean-Etienne Liotard, and the popularity of Allan Ramsay, the Edinburgh Scot who trained in Rome and Naples (whose portraits, wrote the engraver George Vertue, were ‘rather lick’t than pencilld’), offered British clients who had grown tired of the native tradition an aura of ‘cosmopolitan sophistication’, a ‘more emphatic flavour of modernity’. Ramsay’s portraits, Vertue wrote, were ‘neither broad, grand, nor Free’ – adjectives the English thought particularly descriptive of Englishness – but ‘modish French’, which began to go down well as, under the tutelage of Mandeville and his followers, the British learned to think of luxury as separate from effeminacy, and the pursuit of luxury as the chief driver of economic development and the civilising process. Eventually even Hogarth himself, the ‘champion of all things British against the pernicious influence of the foreign – and above all the French’, went French himself, for example in his double portrait of David Garrick and his wife, Eva-Maria Veigel, of about 1760, where the ‘bright saturated colours’, and the ‘endless flutter of rhythmically curving forms’, asked to be compared with Van Loo as well as with Ramsay.

The final challenge to the cultural cringe, however, began in earnest with the founding of the Royal Academy in 1768, which made the paintings of Britain’s best and most fashionable artists available to a much larger and more mixed public than ever before. This is one of Solkin’s special subjects: the exhibition he curated in 2001, Art on the Line, on the first fifty or so years of the Academy exhibitions at Somerset House, taught me more about British art of the period than any other show I have seen. The main argument for instituting an academy in England, on the pattern of those in France and Italy, was that without the kind of academic training available to students of art on the Continent, British painters would never be able to compete in the most important of all genres, history painting in the grand style, in which images of idealised figures acted out moralised stories from the scriptures and from classical myth and history. The establishment of the Academy in London, however, did little to stimulate the production of history in the grand style, for which there was almost no market. What it did stimulate were new varieties of modern narrative painting, sensational or sentimental, which became thoroughly popular with the Academy’s visitors. ‘The works,’ as Solkin puts it, ‘that won the competition for attention tended to be those that presented novel, even bizarre subjects in a visually striking way calculated to highlight the singular character of the painter’s style. This was where Henry Fuseli truly came into his element,’ first with his gothic Nightmare of 1782, sensational, erotic and sentimental all in one.

There were other attempts to develop a British school of history painting, based on the understanding that ‘the noble themes and ideal forms demanded by academic theorists counted for nothing if they failed to excite the interest of the exhibition-going public.’ Alderman John Boydell launched his Shakespeare Gallery, commissioning artists to paint scenes from the plays; Robert Bowyer opened a gallery of paintings illustrating scenes from Hume’s History of England. These and other such ventures were to be funded both by exhibiting the paintings themselves and engraving them for sale, whether as prints to be framed or as book illustrations. Through the Shakespeare Gallery, and the aptly named Robert Smirke in particular, history painting, if that is what it was, could be a comic as well as an epic or tragic genre, and comic history, of which Hogarth was the acknowledged master, came to be fêted as a distinctively English invention and achievement. Now, Solkin writes, ‘driven by the dual engines of exhibition and print culture … a reasonably well-informed middle-class art audience of unprecedented size and diversity had come into being, and had begun to assert its aesthetic preferences with ever increasing confidence’. Far from suffering from the cultural cringe of earlier generations, this audience was convinced of the superiority of native over European art, and was prepared to declare a preference for genres of painting which had hitherto been regarded as inferior to history painting: portraiture and landscape in particular, where the authority of continental precedents was less oppressive.

It was portraiture that attracted most notice at public exhibitions, especially at the Academy. The portraits that succeeded best with the public were of celebrities, whether people of high rank, officers who had distinguished themselves in the American or French wars, royalty, society beauties, or actors and actresses. Artists competed for positions on the walls of the gallery where their pictures would be most conspicuous: a competition that Reynolds, especially once he became president of the newly founded Academy, almost always won, which sometimes led his understandably disgruntled rivals, notably Ramsay, Gainsborough and Romney, to ignore public exhibitions and to display their portraits in more favourable and less crowded positions in the showrooms attached to their own studios.

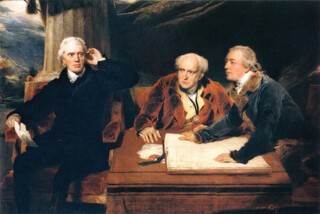

By the end of the century the better-off were commissioning portraits in ever larger numbers, and Solkin demonstrates that some striking class distinctions emerged in the genre. While the war ‘offered noblemen a stage where they could be seen to best advantage, bedecked in gorgeous uniforms’, it also offered opportunities to businessmen, whether in funding the military effort or supplying the forces, to greatly enrich themselves and to grow in importance. Thomas Lawrence’s portrait of the Baring brothers’ partnership was the ‘most-talked’ about picture in the 1807 Summer Exhibition: here was ‘banking as high drama’, with three oldish but energetic men seated around a table with a huge ledger between them, evidently deciding a major financial question. But however vital their contribution to the war effort, it was not sufficient to do away with the stigma that marked the social inferiority of those involved in trade and finance. The children of Francis Baring were embarrassed by the portrait, because, according to the painter and diarist Joseph Farington, ‘they did not like to have their Father exhibited with a Ledger before Him.’

A difference no less marked emerged between the representation of aristocratic and middle-class women. In Henry Howard’s 1798 portrait of Sarah Trimmer, who wrote religious books for children and founded Sunday schools, we see the full ‘Reynoldsian manner’ employed to dignify a plump, rubicund, elderly, middle-class Evangelical – ‘the sort of portrait subject … who would have been virtually unheard of in Sir Joshua’s own day.’ Meanwhile, Solkin argues, ‘noble patrons were becoming increasingly willing to commission and display highly sexualised pictures of their wives and daughters’ – described as ‘false’, ‘showy’ and ‘meretricious’, a word which when applied to women hinted at prostitution – ‘as part of a broader effort to reinforce the distinction between themselves and their social inferiors.’

Interest in grand-style history painting revived briefly after 1811, the year Benjamin West exhibited his vast, hugely admired and sensationally popular Christ Healing the Sick, which he followed up over the next six years with two more ‘religious blockbusters’, but in spite of his efforts and those of Richard Westall and Benjamin Robert Haydon, by the end of the Napoleonic Wars it was becoming clear that ‘in a modern commercial society there would never be a place for an exemplary public art, centred on the idealised forms of the heroic human body.’ Instead, a much more informal, more demotic genre of narrative painting was in favour, what Solkin has called the ‘painting of ordinary life’. The leading figure here was the Scot David Wilkie, whose pictures of peasant sociability were thoroughly topical at a time when the condition of the poor was a cause of great anxiety to the ruling class, not so much on account of their suffering but from a fear that their poverty might lead them to do what the poor in France had done in the 1790s. The first picture Wilkie exhibited at the Academy, Village Politicians of 1806, showed a group of animated Scots arguing in an alehouse over a copy of the radical Edinburgh Gazetteer. He approaches them with humorous condescension: they are fully engaged in their argument, but their bulging eyes and gaping mouths seem intended to reassure us that they are too stupid to be dangerous or to have political opinions worth listening to. Wilkie’s exhibit the following year, The Blind Fiddler, in which an itinerant musician is entertaining an extended peasant family in their kitchen, was an altogether more impressive painting which manages the difficult trick of portraying the members of the family as comic, to be sure (peasants had always been ‘clowns’ in images of low-life), but also as worthy of our respect as individuals, all with their own expressions, together composing a loving family but without sentimentality. They are too much their own people to be capable of collective action to redress their poverty, so that in a different way they are quite as reassuring as the village politicians had been, but without being stripped of their dignity, and the same is true of the figures in most of Wilkie’s later images of the poor. That he was a follower of the younger David Teniers was widely recognised, but it was generally believed too that he had surpassed Teniers – at last, a British painter who could be claimed to be better than his continental equivalent.

A French painter however would have been a bigger scalp, and, as landscape became a more and more valued genre, there was no French artist with a bigger reputation than Claude Lorrain. Solkin ends his magnificent history by comparing two great landscapes by Turner, exemplifying two of the ‘intertwining narratives’ that run through the book. Both pictures derive from compositions by Claude and both were exhibited at the Academy in 1815. The first, Crossing the Brook, is a view of the Tamar Valley, with an imaginary foreground and a slightly less imaginary distance running from Gunnislake Bridge to the far off Plymouth hills. An anonymous reviewer of the 1815 exhibition claimed, bizarrely, that in the two pictures, both ‘purely original’, ‘no affinity to any style or any school’ could be perceived; but Solkin is right to say that Crossing the Brook ‘showed how a close study of the particular forms of British nature could be used to breathe new life into the Claudean ideal’. The Britishness of the scene was reinforced by the presence of two young women in the foreground, one of whom has brought a bundle of washing to the waterside. ‘Although the two girls,’ Solkin writes, ‘may be recognisable as the inhabitants of modern Britain, their peaceful presence by a still pool of water also serves to bring to mind the bathing nymphs of a Mediterranean Arcadia.’ Perhaps the emphasis should be the other way round. When Turner visited the Falls of the Clyde in 1802, he had the good fortune to stumble on a group of naked naiads, or so his watercolour of the occasion suggests; and a good number of other British artists had similar experiences in the years around 1800 – Francis Wheatley, for example, at the Salmon Leap at Leixlip on the River Liffey. These naiads certainly bring the promise of the Mediterranean to chilly northern Europe, but the effect of Turner’s clothed Cornish women is rather to anglicise a motif borrowed from the warm south. They aren’t nymphs: nymphs don’t wash their clothes, having none to wash.

The other picture Turner exhibited at the Academy in 1815 was Dido Building Carthage; or the Rise of the Carthaginian Empire, painted in emulation of Claude’s pictures of ancient seaports surrounded by grand examples of Roman imperial architecture. Flooded with light from the rising sun, this image must have been read as suggesting the ascendancy of the British Empire following the defeat of the French Empire in 1814, and again at Waterloo in 1815 while the Academy exhibition was in full swing. Perhaps too it was intended to suggest the ascendancy of British art, as practised by Turner, over what was seen to be ‘the depressingly uniform character of contemporary French art’, and even over the French painter whom Turner regarded as ‘his greatest predecessor and rival for fame’. According to Solkin, the ‘thoroughgoing classicism’ of the painting ‘eloquently attests to the unsurpassed authority that aristocratic culture continued to command in Britain’, an authority, he believes, that ‘benefited from the active support of British artists, even as they sought to articulate different values and concerns’. Had Solkin chosen to end his book with a different painting by a different artist, the hegemony of the aristocracy might have seemed rather less than absolute. But of all British paintings of the period, none attests more eloquently to the end of the cultural cringe.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.