The Bench

What passed through your mind, old man,

what passed through your mind back then,

staring out beyond the shingle and sea wrack,

the islets and rocks,

to the Olympics on the far shore,

snowy peaks poking through cloud?

I would spot you often on this bench,

smoking your unfiltered Players, gazing into the distance,

reading the grain of the sea,

the currents and wind,

as if parsing the whorls of Eadfrith’s Gospels.

What can a young man – a boy, really –

know of what runs through an old man’s mind?

But I wondered then, and wonder still,

no longer young, sitting here,

gazing as you once gazed at this patch of sea,

ever the same, ever changing,

the gulls and crows busily at work, hovering.

This sky would have been foreign to you,

the light, as well,

but not unpleasing, no, not at all – how could it be? –

swift-moving, full of drama,

weather and clouds rushing east overhead

until caught up in the coastal range,

unburdening themselves of their cargo of rain.

It’s fine light, at its best days like this,

almost pearly, a light mist.

I remember now, after so many years away,

how well it suits the place and suited me then, as now.

I stayed on for years.

But you moved along, taking the long way back,

by ship. You enjoyed the water,

watching it from this vantage or under you at sea.

You were the sort accustomed to moving on.

I spotted that about you straightaway.

You travelled light, the one book,

Njal’s Saga, always in your left coat pocket.

Copper-wire moustache,

sea-reflecting eyes …

You’d long ago been a sailor yourself,

knowing what to take along, what leave behind.

There was more than a bit of the wanderer to you,

the exile, and in your carriage and gait:

no nonsense, erect, never inviting attention

but clearly not of this place.

I watched you carefully that year,

and listened.

It was good to be around a man like that.

One learns, takes on a great deal,

not even half-aware of it, not for many years later.

And not just how words join up,

made to fit properly together like the drystone walls

of a Yorkshire dale, sturdy, serviceable, lasting.

I watched you carefully that year.

That bungalow we’d meet at, those few of us,

rain pouring down outside,

listening to Scarlatti, Dowland, Byrd,

or you reading aloud to us, Wordsworth, Wyatt –

just back there across the road,

torn down, a gruesome condo complex now.

You poured those sounds into our heads.

Who knew what might come of it?

Surely, nothing bad.

I would walk past you many times that year,

sitting here, gazing out at the sea, the rocks.

Who can say what thoughts … ?

Love Chant

You see that big ol’ Kwakiutl in the birdsuit

flapping away, swaying right then left

in the bow of a 50-foot war canoe,

his sidekicks banging the handles of their oars in time:

whack whackwhackwhack whack whack?

Well, honey, that’s about how I feel around you.

Sure, it was all staged, an ethno-spectacular

for Curtis and his actuality film crew;

blow their minds back in New York along the Great White Way,

King Kong before King Kong.

But that’s not the way I like to see it,

and I’ve watched this clip plenty at the museum rainy days like this.

How I like to see it, these boys are getting in the mood,

whipping themselves up for a full-on, all hands, slave raid south,

and that would be in our direction.

Look at all those sun-worshippers out there on Ocean Beach,

matrons, truants, ice cream and cotton-candy vendors,

doing their thing, checking out the kites and cormorants,

listening to Kruk&Kuip call the game over the radio,

slapping on the cocoa butter.

Out of nowhere they’ll come swooping in like pelicans

dive-bombing sardines, gathering up

pink-splotched fatties in Speedos, dogs too,

and tossing them in back of the canoe.

Then, of course, the ceremonial feast:

hormone and nitrate-free wieners,

little tubs of hummus, rice cakes, power bars,

and after that a proper nap, waves gently rocking;

and, first thing on waking, do that dance of theirs they do:

whack whackwhackwack whack whack;

turn that ginormous cedar dugout around

and paddle back the thousand miles or so to Quatsino Sound,

off-load their haul, hose ’em down

and get the lot started on polishing the silver, ironing,

picking lice off the kiddies’ heads, like that.

As for the more unfortunate adult male slaves, well …

Let’s just say next harvest moon when the fright masks come out

and teeth get to gnashin’& a-flashin’ in the longhouse,

warriors gathered round the fire crying whoop-whoop-dee-whoop …

Hey now, my little pullet, that, that’s how …

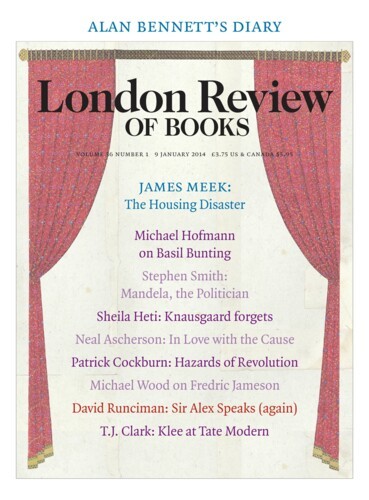

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.