I have plenty of good friends among the Italians who warn me not to eat and drink with their painters. Many of the painters are my enemies, and they copy my work in the churches and wherever else they can find it. Then they criticise it, saying it is not in the ‘antique’ style and therefore not good. But Giovanni Bellini praised me highly in front of some gentlemen.

This is Albrecht Dürer writing to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer in February 1506. After only six months in Venice he is already embroiled in local professional rivalries. Few letters written by artists survive from this period; most that do are pleas addressed to patrons. It isn’t often that we overhear the unedited voice of a premodern European artist. Dürer in his letter is fretful, paranoid, hungry for praise, confused about whether it was the judgments of other artists or of the wealthy that mattered.

From a correspondence that must have been voluminous, for he does write a good letter, only a few dozen sheets survive. But Dürer also left a family chronicle; an intermittent diary, which contains accounts of his parents’ deaths and of the passing of a comet; a log recording a year spent travelling in western Germany and the Low Countries (a similar diary of his Venetian stay seems to have been lost); and a riveting sequence of self-portraits in paint and in pen and ink, including drawings of his left hand and a full-length depiction of himself in the nude. He also wrote several poems of middling quality and copious notes and texts on art theory. Near the end of his life he published three treatises on art and measurement.

Dürer knew that his works would outlive him. In a letter of 1509 he assured a patron that if his painting was kept clean and not handled, and above all was protected from sprinklings with holy water (which was often salted), ‘it will remain bright and fresh for five hundred years. For it is not made the way paintings are usually made.’ But even Dürer would have been surprised by the durability of his fame. He has been ranked among the very greatest of artists for more than five centuries, ever since he published, in 1498, at the age of 27, an edition of the Book of Revelations illustrated with 15 full-page woodcuts: unprecedented displays of technical virtuosity in this most intractable medium.

The present volume is an English translation of the catalogue that accompanied a major exhibition dedicated to Dürer’s early career held last year at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, where he was born. The exhibition didn’t travel, but Dürer’s not quite antique style is well known to the Anglophone art maven, thanks to a ceaseless flow of publications and exhibitions – for example, the show of the British Museum’s Dürer holdings in 2003 or the watercolours from the Albertina Museum in Vienna (recently shown at the National Gallery of Art in Washington).

Last year’s exhibition in Nuremberg followed on from a lengthy research project involving international collaborators, technical examination of the works, and the city’s archives and libraries. The exhibition and the book paint a vivid picture of Dürer’s city, and indeed his neighbourhood with its alert, striving, ingenious citizens. The city was wealthy, maintaining a trade route to the emporium across the Alps, Venice; and politically free, uncowed by prince or bishop and, as the site where the imperial insignia and relics were stowed, enjoying the protection of the Holy Roman Emperor. There was no university. Boys destined for the clergy or the law learned Latin at the school of the church of St Sebald. The sons of the patriciate, like Pirckheimer, studied at the universities of Padua, Pavia or Bologna. Dürer probably studied German, penmanship and arithmetic at a privately run school intended for children who would go into trade. He may have been involved with the short-lived Poet’s School, an academy dedicated to the study of ancient letters established in the city in 1496 by Conrad Celtis, the wandering humanist scholar, who was crowned as imperial poet laureate in Nuremberg when Dürer was 16. Dürer, it seems, could not read the language but knew some Latin words and phrases. The first printed Latin dictionary and the first printed cookbook were published in Nuremberg – this was a city of publishers. Anton Koberger, a goldsmith who established the city’s first press in 1470, was Dürer’s godfather.

Nuremberg did not allow artisans to band together in guilds for the purpose of regulating crafts and trades. In Venice, the guilds would be vexing: Dürer wrote to Pirckheimer in April 1506 that he had been summoned ‘three times before the magistrates and I have had to pay four florins to their guild’ – presumably for accepting commissions without going through the proper channels. In Nuremberg, by contrast, he was free to shape his own career.

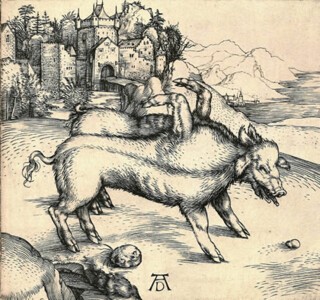

He launched that career with prestigious painting commissions. In 1496 he was hired to paint a portrait of the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, whom he may have met through Celtis, and shortly afterwards to produce a religious painting for the same patron’s palace chapel in Wittenberg. He painted brilliant portraits of other Nurembergers. At the same time he was courting a far-flung and anonymous public who ultimately brought him much greater fame than any previous German artist: the consumers of woodcuts and engravings. In these works Dürer depicted familiar sacred stories, including the lives of Christ and the Virgin, as well as such esoteric profane subjects as Hercules at the Crossroads, Nemesis and a colloquy of four nude women who might be witches. He marked all his works with his monogram, a capital D nested within a capital A. Dürer’s engravings preceded him to Venice, rousing the envy of the Italian artists. As early as 1505, the Alsatian humanist Jakob Wimpfeling, in his Epithoma rerum germanicarum, a treatise on German lands, cities and notable citizens, described Dürer as ‘the most excellent German artist of the day’, adding that his ‘most perfect images’ had been ‘transported to Italy by merchants’ and are ‘esteemed by the most worthy artists not less than the paintings of Parrhasius or Apelles’ (which no modern person had ever seen, but never mind).

In his notes and writings on art theory, the first written as early as 1504, Dürer laid the groundwork for a conception of artistic value detached from manual skill. The exhibition catalogue shows that his early thinking on the geometric construction of the human figure was rooted in methods developed by local architects and master masons, as expounded in several printed handbooks, illustrated with woodcuts, of the 1480s and 1490s. He was also moving towards the articulation of a truly new understanding of art-making as neither a labour-intensive craft nor a matter of mathematical construction, but an inimitable creative performance. In his treatise on human proportions, published in the year of his death, 1528, Dürer wrote that

only powerful artists will be able to understand this strange speech: one man may sketch something with his pen on half a sheet of paper in one day … and it turns out to be better and more artistic than another’s great work at which its author labours with the utmost diligence for a whole year. And this gift is miraculous.

Dürer’s true legacy was his self-invention. He emboldened other artists, often much lesser talents, to break free from the hierarchic painting workshops devoted to the assembly of large altarpieces and strike out on their own, selling small paintings and sculptures as well as prints and even pen drawings. The print created a demand for works that gave direct access to the artist’s style, a demand that could only be satisfied by drawings. Dürer and his epigones, as well as a few peers and near peers such as Lucas Cranach the Elder, Albrecht Altdorfer, Hans Baldung, Hans Burgkmair and Hans Holbein the Younger, made prints as well as paintings, and cultivated in their collectible drawings precisely those features of linear style which could not be reproduced in print. All these artists were aware of the new culture of art flourishing in Italy and ventured far beyond the traditional repertoire of religious subjects, following poets and scholars into Roman history and pagan mythology as well as the iconography of everyday life, including the local landscape, costumes and customs. They developed recognisable personal styles that an increasingly knowledgeable public, aided by signatures and monograms, learned to match to names.

The fine-grained portrait the exhibition provides of Dürer’s immediate surroundings – his family and his city – is memorable. His self-involvement is less surprising in the context of autobiographical documents produced by other citizens of Nuremberg, including his own father, who wrote to his wife in 1492 to boast about his meeting with the Emperor Frederick III (recent analysis of the ink has dispelled doubts about the letter’s authenticity). In the family chronicle he composed in 1524, Dürer quotes his father’s written accounts of the births of his 18 children, only three of whom survived to adulthood. The exhibition assembles a sequence of portraits of Nuremberg citizens, by Dürer and others, revealing with perfect clarity how innovatively Dürer individuated female subjects, whose features had traditionally been rendered as blander and more generalised than those of male subjects.

The envelope of clan, neighbourhood and city did not necessarily entail parochialism. The exhibition lists the Nurembergers, including friends of Dürer, who had been to Jerusalem. The aim of this historical contextualisation, according to the catalogue’s editors, Daniel Hess and Thomas Eser, is to demystify Dürer and make him seem less singular. We ‘owe’ the pioneering figure of Dürer, according to the catalogue, to his neighbourhood or ‘constellation’, an explanation that offers an ‘alternative to the idealistic perception of the autarkic genius’. The contributors to the catalogue are also unwilling to read Dürer’s works as directly registering his experience. The watercolour landscapes, for example, have traditionally been seen as impressions of real places created on site during day trips or longer journeys. Rather, it is argued here, the landscapes were carefully contrived exempla or demonstration pieces, designed to establish their maker as an authority or to provide evidence of his travels: they functioned as tokens in a social game. According to the catalogue, we should not read the watercolours as engagements with the natural world because there is no evidence in written sources that artists in this period thought about landscape in such terms. One might well wonder why the authors don’t have more confidence in the drawings themselves as sources. The catalogue frequently strikes such notes of caution, as if there were a danger that the public might succumb to a thoughtless cult of genius.

The professional habitus of many art historians is negative, debunking, normalising. In the decades after the war empiricism and interpretive sobriety, in Germany, were the scholarly antidote to idealism, ideology and cant. The quincentennial Dürer exhibition, staged at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum a year before the Munich Olympics, took up at long last the cue offered by Erwin Panofsky in The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer, published in 1943, still the gold standard among art historical monographs. That exhibition offered a non-chauvinistic picture of an intellectually alert and internationally oriented polymath. Last year’s exhibition stuck closely to this model. Breaking finally with Panofsky, however, this book downplays Dürer’s tendency to inscribe himself in his own works, and not only through his monogram and his style. The exhibition presented ample evidence of Dürer’s obsession with self-presentation, yet the authors consistently deflect biographical interpretations of the works. It seems clear to me that Dürer, with his lanky body, abundant hair and beaked nose, cast himself in his own work, as Hercules, as Orpheus, as the Prodigal Son, and as a sybarite in a bathhouse. All these works are about desire and sensuality. It is difficult to say anything sensible about premodern homosexuality or bisexuality, but perhaps not impossible. The catalogue simply cuts short any inquiry by invoking a normalising historical context. A drawn profile portrait of a laughing Pirckheimer, for example, signed by Dürer, is supplemented by a Greek phrase, written in Pirckheimer’s own hand: ‘with a cock up the ass’. The exhibition catalogue approvingly cites two scholars who tried to explain this inscription either as an erudite comment on the unflattering likeness or as a parody of conventional humanist epigrams. But there is surely more to be said. The catalogue comes across as pedantic if not priggish when it dismisses other scholars’ attempts to relate the inscription to Dürer’s and Pirckheimer’s sexuality as ‘methodologically problematic’.

Dürer invites a biographical approach because his work so often displays a tension between, on the one hand, sensory perception as the inescapable framework of existence and, on the other, the supraindividual ideal furnished by mathematics. Traditional painting offered several ways in which real perceptions and experiences could make their way into the work: landscape details in the background of a religious painting, for example, vignettes of everyday life in the holy stories, or embedded portraits of real people. Dürer exploited all these opportunities. He took an unprecedented interest in his workshop models, the men, women and boys he hired or persuaded to strike poses. His pen often lingered over their physiognomies, allowing their personhood to overwhelm the original limited descriptive task.

At the same time he was studying the mathematics of proportion, lured by the promise of arriving by measurement and calculation at an essential beauty, which resided in no human model. In the dedicatory preface to his treatise on proportion of 1528, framed as a letter to Pirckheimer, he reveals his defensiveness about German art:

It is obvious that in drawing and handling of colours German painters are not unskilled, even if until now they have been lacking in the art of measurement as well as perspective and the like. One may well hope that when they acquire this knowledge as well and so combine practice and theory, they will in time take second place to no other nation.

Dürer imagined the ideal as something that smoothed out the irregularities of experience. Landscape, however, seems to resist such idealisation. No theory of proportion can explain the appeal of natural beauty or its double in paint. Dürer’s landscape watercolours remain emblems of a new concept of artistic authorship grounded in curiosity, desire and attentiveness to the real.

By insisting on space for artmaking beyond the traditional service to church or court, Dürer was exposing art to experience. His restlessness, his quest for recognition, his obsession with his mirror, and his joyful embrace of the creaturely world, including animals and birds, are the keys to the appeal of the early work. Later in life, beyond the scope of this volume, his preoccupation with art theory and with the inward-looking religiosity expounded by Luther would temper these high spirits.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.