The first return to Treasure Island was made by Robert Louis Stevenson himself. Fourteen years after the novel was published, Longman’s Magazine published ‘The Persons of the Tale’, in which Captain Smollett and Long John Silver step out of the narrative after the 32nd chapter to have a chat ‘in an open place not far from the story’. Stevenson has the two men wonder whether there is ‘such a thing as an Author’, and – if there is – whose side he’s on. The captain berates Silver for being a ‘damned rogue’; the rogue retorts: ‘Now, dooty is dooty, as I knows, and none better; but we’re off dooty now; and I can’t see no call to keep up the morality business.’ The captain is sure that the author is ‘on the side of good’ (he means on his side). ‘“And so you was the judge, was you?” said Silver, derisively … “What is this good? … by all stories, you ain’t no such saint … Which is which? Which is good, and which bad?”’ As the captain starts to denounce Silver again, the piece ends with the captain saying: ‘“But there’s the ink-bottle opening. To quarters!” And indeed the author was just then beginning to write the words: chapter xxxiii.’

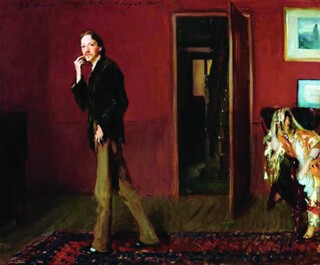

‘The Persons of the Tale’ isn’t a sequel in the conventional sense, and it doesn’t rely on the reader’s interest in something ‘to be continued’ (we know how the story continues). Instead it entertains possibilities that lie within or behind the pages of the original book, in the gaps between words and chapters. The characters take orders from the storyteller, but the tale can’t contain their whole story: after all, ‘the ink-bottle opening’ also led to this ‘open place not far from the story’. In one sense, all spaces and characters are open places in Stevenson’s writing. ‘The reader never does feel quite at home with Stevenson’s characters,’ Chesterton observed. ‘He cannot get rid of an impression that he knows too little about them; though he knows that he knows all that is important about them. His tragedy is that he knows only what is important.’ It’s true that we’re rarely at home with these people – in part because home is one of the places they are least interested in – but this needn’t be a tragedy. Henry James saw Stevenson as ‘the writer who has most cherished the idea of a certain free exposure’, adding that, ‘to his view the normal child is the child who absents himself from the family circle.’ Stevenson’s most valued version of the normal is the intrepid or the agitated: if the author is at home with anybody, it’s with those who can’t be house-trained. Sargent’s portrait of Stevenson and his wife, Fanny, captures this mood.

Stevenson saw ‘comicality’ and ‘wit’ in the painting, writing appreciatively to Sargent about the ‘caged maniac lecturing about the foreign specimen in the corner’. But there are possible escape routes from the cage (Fanny said the painting was like ‘an open box of jewels’): the door which leads to other doors, or the pictures on the wall which offer portals to partially glimpsed elsewheres. Our eyes, like the eyes we see in the image, are encouraged to search for what is absent from it or just out of view. Stevenson had hoped that Treasure Island – a story of strange absences and absentings – would appeal to a similar need to go looking for adventure, or for trouble. He said that the tale was ‘as original as sin … If this don’t fetch the kids, why, they have gone rotten since my day.’ Gone rotten, he meant, by not being nearly rotten enough.

The difficulty we have with Stevenson’s people and places is often related to a weird precision in his writing. Take one sentence from early in the book, just after Long John Silver makes his first entrance ‘with a face as big as a ham’, all ‘intelligent and smiling’. Silver has left the room and the squire shouts after him that all hands should be on deck by four in the afternoon: ‘“Aye, aye, sir,” cried the cook, in the passage.’ Grumbling to his publisher about emendations to a manuscript, Stevenson wrote: ‘I must suppose my system of punctuation to be very bad; but it is mine; and it shall be adhered to with punctual exactness.’ A proofreader might have been tempted to cut the comma before ‘in the passage’, but then readers would have been less likely to notice the oddity of the phrase, one that seems to keep Silver in our mind’s eye for a shade longer than is necessary. Perhaps we are being asked to imagine how he might look as he acknowledges the order, or even simply to think about why we are given this detail at all. (Is Silver somehow different in the passage? Should we pay closer attention to him when we can’t see him?) In its very assiduity to locate the man, the phrase arouses the feeling that he can’t be located. The comma is like the wall between the characters, or like the half-open door in Sargent’s painting – a barrier that obscures and lends significance to the view.

The intensity of Treasure Island’s feeling that things are only partially knowable, the sense it gives of a gaze which is both searching and perplexed, sets a tricky challenge for editors. John Sutherland’s excellent new edition is shaped by the literary detective work in which he specialises (one appendix includes sections on ‘When and Where Is Jim Writing?’, ‘Why Does Stevenson Not Hang Long John Silver?’, ‘How Old Is Jim?’ and ‘Who Owned the Parrot before Silver?’). Generous, engaging notes at the bottom of the page contain a wealth of information about monetary values, slang terms, the history of piracy, textual borrowings and revisions, and much besides. The notes often provide helpful orientation, but orientation is not always what readers need or want here. When Jim is helped down from a horse, a note reads: ‘Jim, we remember, is not yet fully grown.’ Had we forgotten? When the pirates scour the inn in search of something called ‘Flint’s fist’, Sutherland clears up any confusion: ‘They are looking for the map he drew up.’ But part of the drama here relies on readers being left in the dark, or left to look for themselves. Once on board ship, Jim considers Mr Arrow: ‘We could never make out where he got the drink. That was the ship’s mystery. Watch him as we pleased, we could do nothing to solve it.’ There is a superscript number next to the word ‘mystery’ and my heart sank a little as the corresponding footnote began: ‘Later it emerges, of course …’ In Chapter 1, Dr Livesey threatens Black Dog: ‘If I catch a breath of complaint against you, if it’s only for a piece of incivility like tonight’s, I’ll take effectual means to have you hunted down and routed out of this.’ Sutherland adds: ‘A word like “place” seems missing … Possibly we are meant to understand that the doctor is speaking under pressure, and therefore ungrammatically.’ And possibly, in a book haunted by missing places and spaces, we are meant to wonder where on earth ‘this’ might lead.

Treasure Island is ruled by a map, but for Stevenson, a map, like a story, is a way of drawing a blank. It’s a projection of and a spur to desire; you read into it as well as from it. In ‘My First Book’ he recalls that, on the map he drew before he wrote the story, ‘I had called an islet “Skeleton Island”, not knowing what I meant.’ He then claims that he mislaid this copy of the map and made another, ‘But somehow it was never Treasure Island to me.’ The last words of ‘My First Book’ have a certain archness: ‘Even when a map is not all the plot, as it was in Treasure Island, it will be found to be a mine of suggestion.’ ‘Found’ carries a glint, as does ‘mine’. What we find in a map is a renewed sense that something is lost or eluding our grasp. If we dig in the right place, we might reasonably hope for all kinds of precious metal from a mine (buried treasure even), but what we get here is yet another set of ambiguous markings. The hint is that the map is the treasure, and that the treasure itself is a catalyst rather than a terminus. What is it, Stevenson seems to be asking, that we really want from a treasure hunt? In the book, Jim is surprised by the frenzy with which the mutineers greet the map: ‘You would have thought, not only they were fingering the very gold, but were at sea with it besides, in safety.’ It’s as though the treasure serves as an alibi for the fascination with the map, or the voyages the map allows people to make. Trelawney speaks for others too when he cries at the beginning of the book: ‘Hang the treasure! It’s the glory of the sea that has turned my head.’

Talk of heads turning, when placed so close to a cry for hanging, is unnerving as well as bracing. It’s a reminder that, despite the telegraphic speed and concision of Stevenson’s prose, his style often carries an unease within it. Or rather, the speed is a way of registering the unease. In some stories, if one sentence ended with ‘without another word, he passed away’ and the next began with ‘In the meantime the captain’, the blithe change of subject might be a way of proclaiming a need to turn to other adventures, to keep the page-turners interested. But when this happens in Treasure Island, it’s clocked as a potential evasion: a page later, the narrative almost trips over that dead body.

Treasure Island has a way of conveying great drive and urgency while at the same time making you wonder what the urgency is about. At the end Jim recalls carrying the treasure to the ship: ‘Day after day this work went on; by every evening a fortune had been stowed aboard, but there was another fortune waiting for the morrow.’ Stevenson’s surprising words are often his small ones – why the word ‘but’ here, not ‘and’? Jim might be expected to sound delighted, but he sounds beleaguered, weighed down by the burden of getting more of what he wanted. Everyone seems hungry to make a fortune, but on nearly every occasion the word ‘fortune’ pops up, it refers not to the treasure, but to chance, to accident, to people committed to pushing their luck. In this book, a fortune isn’t always something you are pleased to take possession of.

Stevenson described writing Treasure Island as ‘a set of lucky accidents’, and it’s striking how many of its most famous episodes – Jim’s overhearing of Silver’s plot while he’s inside the apple barrel; his precarious voyage in the coracle; his lying down to sleep in a stockade infested by pirates – arise from the accident of the protagonist finding himself in an enclosed space. Treasure Island is a book of tight spots, of spaces that are both protective and hazardous, and one of the vicarious pleasures of reading it comes from being privy to Jim’s ravenous need to be there and to see it all, regardless of what may transpire. ‘My curiosity, in a sense, was stronger than my fear,’ he says; later on, ‘curiosity began to get the upper hand, and I determined I should have one look.’ When he finds himself in the apple barrel ‘in the extreme of fear and curiosity’, it’s no longer simply that curiosity wins out over the fear; fear itself is translated into a kind of curiosity. The feeling is close to what Stevenson elsewhere called ‘the sympathy of fear’.

Fear draws the child towards, rather than away from, its object. When Jim is meant to be on his guard, he lets it down for the sake of absorbing what is happening: ‘I will confess that I was far too much taken up with what was going on to be of the slightest use as sentry,’ he admits. On another occasion: ‘Even then I was still so much interested … that I had quite forgot the peril that hung over my head.’ One reason Jim has proved so winning a figure is that he stands as a surrogate for a particular kind of reader: his roving eyes and imagination are always on the lookout for a way to locate fresh sources of disquietude or bewilderment. It’s worth recalling that Jim is first attracted to Silver because he tells brilliant jokes and stories, even though the boy admits that he often doesn’t get the point of either. The first stories told in Treasure Island are those by Bones in the Admiral Benbow pub: ‘His stories were what frightened people worst of all. Dreadful stories they were.’ And yet, ‘I really believe his presence did us good. People were frightened at the time, but on looking back they rather liked it.’ This is close to the good that loiters with shady intent in Stevenson’s own writing as he plays around at ‘the extreme of fear and curiosity’ to see what might come of it. This isn’t quite to agree with Captain Smollett when he says: ‘I know the Author’s on the side of good.’ It’s closer, perhaps, to Stevenson’s response to a reviewer who asked why he didn’t nail his colours to the mast: ‘Ethics are my veiled mistress; I love them, but know not what they are.’

Many people have wanted Stevenson to grow up – and to grow up to be a novelist. ‘It is so much easier to finish the little works than to begin the great one,’ J.M. Barrie complained. ‘He experiments too long; he is still a boy wondering what he is going to be.’ Stevenson admitted that ‘as I go on in life, day by day, I become more of a bewildered child: I cannot get used to this world.’ What might Treasure Island look like, then, if it grew up a bit? Perhaps something like Andrew Motion’s novel Silver: Return to Treasure Island. It’s 1802 and Jim Hawkins is now in his fifties; his son, Jim Junior, the main narrator, is nearly 18. So the younger Jim is a little older than Stevenson’s narrator (Jim Hawkins was around 14) and is not so much wide-eyed as dewy-eyed. The last words of the first chapter set the tone: ‘There, in the deepest solitude of green and blue, I fell to thinking about my life.’

Jim Junior lives with his father in a pub on the Thames and has had to listen to his father telling the story of Treasure Island hundreds of times. But then he receives a visit from a mysterious stranger, Natty, Silver’s daughter. Silver, rather dispiritingly, is now ‘a reformed character’. That said, he’s organised an adventure for Natty and Jim Junior: Jim Junior is to steal his father’s map, and the youngsters are to return to the island to get the ‘treasure not yet lifted’ that was mentioned at the beginning of the original novel. Motion has noted that the ‘secret engine’ of Stevenson’s books is the complex relationship he had with his father, and Silver has the same engine, although it isn’t a secret. In several interviews, Motion has explained that he wrote the novel a short time after the death of his own father (‘I couldn’t have written it before … while I was still a child’) and glossed various scenes from the book in relation to this event (Jim Junior seeing his father on shore as he begins his voyage, for example – ‘That’s me saying goodbye to my dad’). There are several echoes along the way of the father Motion described in his memoir, In the Blood, and in the poems in The Cinder Path.

Motion is acutely aware, as Stevenson was, that intense devotion can become an unwanted demand. What goes for fathers goes for precursor texts too; when the captain of the second voyage to Treasure Island tells Jim Junior that he honours his father, Jim thanks him but adds: ‘It is my own wish to travel as myself, not as anyone’s relation.’ So it might seem unfair to make comparisons between Silver and Treasure Island, yet this is what Motion’s novel itself frequently does (‘I wished my father and Mr Silver had been there to see it as well; the story unfolding before us was so like their own, and yet so different’). The differences are easier to spot than the similarities. In Treasure Island the early death of Jim’s father is not dwelled on; the day after the funeral, ‘I was standing at the door for a moment full of sad thoughts about my father, when I saw someone drawing slowly near along the road.’ He is sad ‘for a moment’: this is one of those moments in Stevenson when the desire to move on allows things to be left unsaid. In Silver, the decision to leave the father behind is accompanied throughout by Jim Junior’s worries about this perceived betrayal. Motion’s narrator is not just older than the original Jim, but cherishes a sense of being wiser too. When Silver turns to him and says Jim Hawkins ‘was like a son to me’, Jim Junior notes: ‘These last few words sank into me as heavily as stones. And as often happens at moments of especial intensity in our lives, I became conscious that a part of my mind had withdrawn, and was observing its own operations.’ This shift from first-person singular to plural is common in Silver, and makes for uncomfortable reading. The original Jim was, as Dr Livesey said in Treasure Island, ‘a noticing lad’. Jim Junior is always having a thought: ‘It was a moment of the most complex solemnity’; ‘and that is another paradox’; ‘I now see my reasoning was casuistic, and I cannot admire it’; ‘this left me with a deep question’; ‘All this might have been alarming, yet it filled me with a profound sense of quiet.’ Sometimes you get the sense that this kind of thing is being sent up a little, but not often enough to make you think that you shouldn’t be taking these pronouncements very seriously.

The last mention of silver in Treasure Island was not in reference to Long John, but to the bar of silver that still lies unfound. It’s the value and cost of this silver that Motion is interested in. ‘Pieces of eight! pieces of eight!’ are, after all, made from silver; the coins were the first truly global currency, the metal coming largely from the silver mines the Spanish exploited in Peru through forced native labour. The shadows history casts on treasure bring Conrad’s influence on Silver into view – and with it, Stevenson’s influence on Conrad. The latter’s journey to the Congo led, as he put it in his essay ‘Geography and Some Explorers’, to ‘the distasteful knowledge of the vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience and geographical exploration. What an end to the idealised realities of a boy’s daydreams!’

Motion’s return to Treasure Island involves lengthy disquisitions on the evils of empire and slavery (the three maroons left there in the original story have taken advantage of a slave ship that has run aground and have set up a colony). There is a gallant attempt to save a slave called Scotland and many others with him, but not without a fanfare: ‘I saw I was mistaken in supposing I had been born into a gentler age than my father … nothing had been done to alter a fundamental fact about our human nature – namely, the appetite for savagery passes unchanged from generation to generation.’ Soul-searching abounds: ‘What had I become, stepping onto the island? … Maybe we would become barbarians ourselves, if we punished the barbarity of the pirates? Maybe we were no better than them, in wanting to gratify our desire for wealth?’ It’s all rather indulgently rhetorical and doesn’t leave you much room to wonder which side the author’s on when it comes to the morality business.

When the unnamed narrator of Sara Levine’s novel Treasure Island!!! reads Stevenson’s book, she is struck primarily by how cramped her own life is compared with ‘the book’s open air’. ‘When had I ever done a foolish, over-bold act? … How can I become the hero of my own life?’ she asks, before deciding that Treasure Island is the accident that was waiting to happen to her, a book that was ‘cosmically intended for me’. And so, armed with what she sees as Stevenson’s four Core Values – Boldness, Resolution, Independence and Horn-Blowing – she begins her journey towards a more adventurous selfhood: ‘You know what Jim Hawkins would say? He’d say what good is a life if it can’t be dashingly used, cheerfully hazarded?’ Part of the novel’s comedy comes from Levine’s knowing that Jim wouldn’t quite say this, or perhaps even think it, but might still act as if he did. So several questions are given room to breathe in the novel’s open air: is our 25-year-old heroine using Treasure Island to enrich or to avoid her life? Is the very thoroughness of her need to turn Stevenson’s tale into a self-help book part of the problem, not the solution?

The narrator’s long-suffering boyfriend, Lars, is adamant that Treasure Island is ‘a story, not a user’s manual’. But Levine’s novel asks: what can we use fictions to do for us? Stevenson’s story is something people can’t seem to leave alone: Levine’s narrator knows that you’ll have ‘read it yourself or heard about it or seen the movie or maybe eaten in the restaurant Long John Silver’s’. It has lent itself to sequel, to prequel and to endless adaptation partly as a result of Stevenson’s commitment to leaving us a space in which to run riot. Unlike Motion, Levine manages to get serious by retaining a sense of humour:

‘Lars, I want us to talk seriously about Treasure Island,’ I said as we reached my apartment. ‘Like, pretend we’re in a seminar.’

‘Piracy and the expansion of the 19th-century nation-state,’ he replied. ‘I’ll talk for twenty minutes and then turn it over to you and Jimbo.’

‘Jim,’ I said. ‘Jim Hawkins’ …

‘What’s a “19th-century nation-state?” I asked later as I searched the tangled sheets for my underthings. But Lars had drifted off to sleep.

The exchange makes fun of the narrator’s fantasies about Treasure Island, but it’s also in tune with an aspect of the original book. Like Jim, she’s caught up in something larger than she can imagine, and readers wouldn’t necessarily want her childishness – if that is the right word – educated out of her. As part of her plan to be bold, she steals some cash from work, buys a yellow-naped Amazon parrot, and moves in with Lars:

‘No, honey, don’t let him out,’ I told Lars. ‘I know more about animal behaviour than you. A cage is a bird’s home. It safeguards him from the overwhelming complexity of the world. Letting him out for some exercise would be like throwing a person off a cruise ship for a little swim.’

‘People swim off cruise ships all the time,’ Lars said.

Her lecture responds to Stevensonian preoccupations as well as to the drama unfolding in the book: a cage, like a home, might be imagined to be snug or suffocating, just as walking the plank could be seen as a chance to dive into something new.

The narrator is the bird that does and does not want to fly the nest. She loves the moment in Treasure Island when Jim absents himself from the family circle, commenting that ‘you have to get away from your cove and open yourself up to strangers,’ but she’s soon moving back in with her parents, and – like Stevenson – she’s haunted by a view of domestic space that seems to open up an avenue towards its opposite: ‘I don’t cherish the ranch house as an architectural form, but my parents’ house ran to so many rooms that, in daylight, I could fall into a stride and imagine myself aboard the Hispaniola.’ Is this a way of retreating from adventure, or a way of looking for it? On occasions like this, Levine’s book becomes at once a quizzical inquiry into the domestic interior and an arch defence of the need to make and take voyages where you can. The playful shifts of scale are akin to those in A Child’s Garden of Verses, where cabin fever is wondrously translated into a feeling for the miracles that can be worked on enclosed spaces: ‘We built a ship upon the stairs,/All made of the back-bedroom chairs.’ Another ambitious voyager exclaims:

O it’s I that am the captain of a tidy little ship,

Of a ship that goes a-sailing on the pond;

And my ship it keeps a-turning all around and all about;

But when I’m a little older, I shall find the secret out

How to send my vessel sailing on beyond.

‘What wonderful fancies I have heard evolved out of the pattern upon tea-cups!’ Stevenson remarked in his essay on ‘Child’s Play’. In the poem, we are privy to a fantasy of growing up – or a fantasy of growing more once you’ve grown up – conducted in the security and safety that allows for these flights of fancy. Like much of Stevenson’s art, it understands that the ability to leave home (and the ability to return to it) may be most productively nurtured in a home that furnishes you with the time to dream up such rehearsals and reversals of fortune. As the rhyme intimates, you need a ‘pond’ on which to practise your visions of ‘beyond’. Most of the best lines in Levine’s novel come from somebody who plays things down rather than up. It turns out that the narrator’s mother had an affair many years earlier while her father taught a summer school; she left home for six days, and then returned. The daughter is furious: ‘I can’t believe you are minimising this. You had sex and because you liked it, you left us?’ ‘It wasn’t the end of the world,’ the mother replies. ‘It was just an adventure.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.