Iris Robinson is, at the time of writing, under acute psychiatric care in a Belfast hospital, after a BBC Northern Ireland documentary revealed that she had, at the age of 59, solicited £50,000 from two property developers to help fund a business run by her 19-year-old lover, Kirk McCambley.

She has some experience of the mental health profession. In June 2008, days before she embarked on the affair, she said on the radio: ‘I have a very lovely psychiatrist who works with me in my offices and his Christian background is that he tries to help homosexuals – trying to turn them away from what they are engaged in.’ This was the interview in which she caused outrage by calling homosexuality ‘an abomination’. The ‘lovely psychiatrist’ was not Selwyn Black, who also worked in her offices and eventually shopped her to the BBC, but a consultant from Belfast’s Mater Hospital, who took a career break shortly after her remarks were made.

Selwyn Black has lectured in counselling at the University of Ulster, and his Christian background is that he has also worked as a Methodist minister and RAF chaplain. He specialised in the victims of trauma, of which there are many in Northern Ireland, and has given talks about the problem of compassion fatigue. He certainly suffered some kind of fatigue from working with Iris Robinson. Her remarks about homosexuality struck him as ‘bizarre’, in that the interview took place on the day her husband, Peter Robinson, went to Downing Street to accept the role of First Minister of the Northern Ireland Assembly ‘and there really was a sense that Iris had stolen his thunder’.

Black, who was hired as her political adviser, does not say when he decided to keep, rather than delete, Iris’s text messages, the intimacy of which is startling. He has, at any rate, more than 150 of them still on his phone. ‘Just cut links with Kirk,’ she texted in the autumn of 2008. ‘God’s word was very clear on it. He was reasonably OK. I am not.’ Also: ‘Everything is a reminder. Wherever I go. My home, my church, my car, my music and of course the roads we drove.’ Despite the ardency of these messages, it was not until he saw the couple together that Black realised what had gone on. ‘I had an increasing sense that this relationship was much more than I had ever construed and that it had huge consequences for all concerned.’ It is hard to blame him for being so slow; the boy was only 19. Iris had been hiding in plain sight. Black’s emotions may have been, in the circumstances, quite strong.

He was a man trained to listen, but not to this. Iris may have talked this way to everyone – religious people can be so intense – but it is possible that not all of them wanted her to. Did Black find the intimacy of her messages seductive, before they became unsettling? What was the drama between them? The key may be in his response to an instruction, sent from Florida, about the £50,000 Iris wanted back from Kirk, now that the relationship had soured. Black was to assign ‘25k [to] Light and Life Free Methodist Church Dundonald, and other to me.’ To which Black thunders: ‘Where is god in all of this?’

If Iris Robinson is attracted to the role of penitent, she has the rest of her life to play it out. It is tempting to wonder whether she ever acted it with her husband, who is described as ‘controlled’, ‘cold’, ‘taciturn’, ‘shy’. The hope must be that her current psychiatrist can tell the difference between a state of mental health and a state of grace. Let us also hope that he does not vote for the Democratic Unionist Party.

She was born Iris Collins in 1949. Her mother was called Mary and her father was called Joseph. He was a demobbed soldier who died, just before her sixth birthday, of a chronic illness contracted on active service in the Far East. Iris, who describes herself as ‘Daddy’s girl’, was, she says, devastated. As the eldest daughter in a family of seven, she was used as a ‘substitute mother’ by Mary, who went out to work to ‘keep the family together’: destitution meant the family being split up among relatives or by social services. It was a core value; Iris Robinson has done much since then to ‘keep the family together’, sometimes in unusual ways.

At 16, she enrolled at Cregagh Technical College, where she ignored the most handsome boy in the school in order to win him. They kissed for the first time when she was 16 and Peter Robinson 17. They married four years later, in 1970. These were the early days of the Troubles. In 1971 Peter Robinson became politicised when his friend Harry Beggs was killed by an IRA bomb. He was an early member of the DUP founded by the magnificent fundamentalist preacher Ian Paisley.

Their first child, Jonathan, was born, and Iris was brought low by post-natal depression. She sought relief in her local church, where, one day, she found her faith validated by a lovely coincidence. The speaker told the story of a soldier dying in Galwally hospital, and Iris was thrilled to realise that this man, who had been ‘saved’ on his deathbed, was her very own father. It was around this time that she herself was ‘saved’ and moved from Presbyterianism to a more evangelical Protestantism. The spiritual union with both heavenly and earthly fathers did not protect her from further crisis. She was hospitalised many times in the early 1980s – years her husband spent protesting the Anglo-Irish Agreement – and in 1983 had a hysterectomy. She had three growing children by then and was 34 years old.

The Anglo-Irish Agreement, finally signed in 1985, outraged Ulster Unionists. Eighteen months later Peter Robinson led an ‘invasion’ of the South by 500 loyalists, and he was arrested, in Clontibret, Co. Monaghan. But gesture politics were not his natural game. Peter Robinson was a strategist, a back-room man. He had been, since 1977, a member of Castlereagh Borough Council. He became an MP in 1979 and was elected to the various assemblies established and dismantled during the peace process. He rose through the party, and though the DUP continued to be led by Paisley, Robinson, an astute and useful politician, seemed prepared to bide his time. In 1989 Iris joined Peter on Castlereagh Borough Council and her own highly successful public career began. The children were almost reared. The tensions of the early and mid-1980s seemed to be over as the couple started to enjoy the hard work and keen pleasures that come with political power.

It was also in 1989 that Kirk McCambley was born. It is difficult for grown-ups – the adults who lived through the tedium and anguish of the Northern Troubles – to imagine what this boy’s life has been like. When he was five, the first IRA ceasefire was declared. When he was eight the second IRA ceasefire was declared. He probably does not remember the sound of a distant car-bomb. He does remember seeing Iris Robinson come into his father’s shop, Select Cut, when he was nine. Iris was good friends with his father, Billy McCambley, a butcher with a drink problem (a fact that makes you fear for his fingers). Before Billy died of cancer in 2008 Iris promised she would look after his son, which she did, taking him for walks along the banks of the River Lagan, talking things through. ‘She looked out for me,’ he said. Whether her seduction of this bereaved young man was lyrical or cynical, we can assume, along with those who watched the BBC documentary – watched while texting, emailing; with their mother on the landline, and their mouths wide open – that there was, before that initial adulterous touch, an amount of trembling involved.

And then she gave him money.

The money was used to fund a business under tender from Castlereagh Borough Council for which McCambley was found to be the only suitable applicant. Iris did not declare her interest to the council before it made its decision. For this, she could face prosecution. The affair lasted seven months. She was 60 when it ended. She is 61 now.

In a statement made before the documentary aired, Iris said that ‘severe bouts of depression’ altered her mood and personality. ‘During this period of serious mental illness, I lost control of my life and did the worst thing that I have ever done.’ Her mental state is a matter of some political significance. ‘She is presently receiving treatment from a psychiatrist,’ her husband said at a post-revelation press conference and ‘the solicitor was unable to take instruction from her because of her illness.’ He seems to imply that Iris is in some quasi-legal sense insane.

Being mad in Northern Ireland is different from being mad in any other place. The Robinsons come from a community in which people talk to God and He talks right back to them. ‘I have forgiven her,’ said Peter Robinson. ‘More important, I know that she has sought and received God’s forgiveness.’ These communications from God can be fairly abstract, they can be politically convenient, they seldom involve what the rest of the world call auditory hallucinations, but there is no doubt that the sense of conviction they carry can be overwhelming.

There is also a particular flavour to Northern Irish paranoia. A system of spies, counterspies and informers was in place in the province from the 1970s; British intelligence listened, watched, misinformed. They checked sheets for sperm or explosives with the help of the Four Square Laundry van. Annoyed at long-standing rumours that her husband beat her, Iris has said that ‘this malicious lie was started by the [British] government in an attempt to blacken Peter’s name when he was protesting at the Anglo-Irish Agreement. It took root because I was in hospital 17 times during that period with gynaecological problems.’ This is a lot to unpack. It may all even be true. Slightly more strange is her claim that Peter’s steak was laced with rat poison when they ate in a restaurant on the outskirts of Belfast which had ‘a very nationalist staff’. But then, who’s to say? The loyalist community could trust neither their Catholic neighbours nor the British government to whose queen they professed such shouting, undying and possibly unwanted loyalty.

It is interesting in this context to look at the DUP’s obsession with sodomy, not the activity perhaps so much as the word; one that is to be said out loud, without fear; one that should be repeated, shouted, written down for all to see. Paisley was always a great man for naming and shaming. ‘I denounce you as the Antichrist,’ he shouted, in the European Parliament, at Pope John Paul II. ‘Harlot’ was also a favourite, but this was rarely applied to an actual woman, being reserved for the Church of Rome. The same applied to ‘whore’, as in, ‘of Babylon’. The purity, in this uncracked patriarchy, of their own women, was a given; what they had to guard against were the sins of men. In 1977 Paisley added to the gaiety of several nations when he was shown on the news walking around with a placard that said ‘Save Ulster from Sodomy’. His campaign was a response to the liberalising laws of Westminster, which were threatening to leave this entrenched culture behind. Sodomy, in 1977, symbolised everything. Betrayal. Isolation. The future.

Iris Robinson may not have been in full health when she made her peculiar statements about homosexuality, but if they are evidence that she was unwell, then so are the other members of her party. The radio interview which lost her the sympathy, not just of the wider world, but also, crucially, of Selwyn Black, happened on 6 June 2008. By midsummer, she and Kirk McCambley were lovers. Whatever was happening to her in those weeks, it wasn’t that grey old beast, depression. Indeed, looking at the way she led her life, you might conclude that Iris was more often up than down.

But how far up is a woman allowed to go? Is it mad for a woman from a council estate to adorn her new villa with hand-painted murals, to decorate each room according to a different theme (Oriental, Scottish, Italian). Is it a bit manic to have, in your study, a hand-carved, ten-foot-high, three-ton stone fireplace which you have had specially designed and installed? Is it unhinged to order wallpaper hand-printed with the quotation ‘Non magni pendis quia contigit’ (‘one does not value things easily obtained’) – or is it only counter-productive, because it shows so clearly that you left school at 16? ‘I remember Iris getting a Dulux dog which ate the furniture,’ the DUP MP Sammy Wilson said. ‘She bought a dog kennel the size of a shed. It was so big it wouldn’t fit in the back gate so Peter, myself and his police bodyguard had great fun hauling it over the roof at 1 a.m. when the neighbours were asleep.’

The story of the Troubles became the only story in the North for 30 years, but there were other more normal things going on. Sex was one of them, shopping was another. Southern Irish people have always known this. When the wind changes and the exchange rate is right, they come down to Dublin to do it: Northern women are demon shoppers. After the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, the Maze Prison emptied of former paramilitaries and talk filtered south about the furniture these guys were buying; some man with body parts flying through his dreams, who embraces minimalism, and orders his sofa from Milan.

It was for a Southern audience that Iris first dressed up. When Peter was in court after the Clontibret invasion of 1986, she ‘decided clothes would be my camouflage. I wore a big purple ski-suit one day and an emerald green tartan skirt and sweater another day to show the Republic didn’t have a monopoly on that colour. On the last day, I wore a black dress with a white blouse and bows tied in front like a judge’s gown.’ Iris bought more than clothes. The Robinsons have a house in Belfast, another in London, a flat in Florida and are building a spread in the Belfast hills. The new house, it is said, has a great view: on the left is his constituency, on the right hers.

Like many women, Iris talks about her husband all the time. Their righteous consumerism is presented by her as a joint folly: ‘Peter has over 1000 ties and I have as many bras.’ How much time, effort and organisation does it take to buy a thousand bras? These things have to be fitted properly; it takes about half an hour to buy a bra. Bulk purchase? ‘I’ll take one in every colour’? Maybe you just leave your measurements with Rigby and Peller and phone them up, every few days for a year, or two. Ties, ok, you walk into Charvet and scoop your hand along the rack – delicious – but bras?

Why do women buy lingerie? Because, the cliché goes, they are having an affair. An interest in underwear is an interest in a hidden, sexual self. Some women find the existence of this secret self very empowering. They feel better in a meeting because no one knows how sexy they are, under their clothes. Is it mad to buy them, or mad to count them? How are they stored?

The Robinsons can afford a thousand of everything because they have five jobs between them. In 2007-8 they jointly received £571,939 from their public posts in Westminster and Northern Ireland. Peter employs one son as a parliamentary assistant and their daughter as office manager, while Iris’s staff included, along with all those mental health professionals, their elder son and a daughter-in-law.

Despite all of this, Iris managed to get into debt. When the affair soured and she demanded the money back from Kirk, her thinking seems a little disordered. Perhaps it was the way Selwyn Black brought God into it, all of a sudden. ‘I never intended this to be a buy-off to God,’ she texts back to him. ‘It was an honest and honourable decision. I will be paying back all the monies to contributor A. Contributor B is now deceased and was not to be paid back. I had intended to release £1,000 per month to church. As well as using it to clear the massive debt incurred by me over past year.’ Iris had no compunction getting money for Kirk, and there is a chilling sense of entitlement in the way the decisions of Castlereagh Borough Council fell just as she wanted them to, but once the affair was over, her talent for corruption fell apart.

She was not only incompetent, she also made – apparently under her husband’s direction – a very moral attempt to give at least half the money back. The other half was, according to the deceased man’s family, one of many charitable donations he made in his last days. (Whatever it takes to ask a dying man for money for your 19-year-old lover, Iris had it.) There are as yet unasked questions as to why she gave this half of the money not to her own church, the Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle, but to the Light ’n’ Life Church in Dundonald, of which Peter Robinson’s sister was the pastor. These questions cannot be put to her because her illness puts her beyond the reach of even her own solicitor. It also puts her beyond the reach of her own libel lawyer, and in the feeding frenzy many more allegations have been made. The most interesting is that she had an affair with Kirk’s father, Billy McCambley, which makes the drama of her life even more tragic in the Greek sense. This is better than Phaedra. Or worse.

Here is what she said about Hillary Clinton: ‘No woman would put up with what she tolerated from her husband when he was president. She was thinking only of her future political career. It’s all about power and not principle.’ She sounds almost bitter. It is possible Iris resented her husband’s pursuit of power and had affairs to test him. It is also possible that the exercise of power, for Iris Robinson, packed a considerable erotic charge. This passionate, glamorous woman (this disinhibited, manic psychiatric patient); this bigot, this wife is said to have visited Ian Paisley sometime in the 1980s, to say that she wanted to leave her husband. Paisley, who is rumoured to be, in private, quite a nice man, advised her to try to make the marriage work for the sake of their children.

Iris Robinson was hospitalised on the morning of 2 March 2009, after a suicide attempt the night before. The timeline is important. ‘The family had come across a letter that Iris had written to Kirk,’ Selwyn Black says. ‘It was about midnight,’ according to Peter Robinson, who then gets more specific, ‘between midnight and one o’clock of the 1st and 2nd of March, that all of these events became known to me, when Iris tried to take her own life.’ Black was called to the house the next morning, and found that Peter Robinson had already left for work. There were other members of the family present. Black discovered that Iris had not seen a doctor – they had not been able to get hold of the family GP – so he called a locum. The two doctors arrived together and agreed, ‘straight away’, that Iris should be hospitalised.

Perhaps in response to criticisms of the way the event was handled by Peter Robinson, a psychiatrist from the Belfast Mater Hospital went on local radio to say that it might not be necessary to get someone who has taken an overdose to a hospital immediately after a suicide attempt, that it depends on ‘the nature and extent of the overdose’. This was not the same ‘lovely psychiatrist’ who stood down from his post after Iris’s remarks about curing homosexuality. This was a different psychiatrist called Graeme McDonald. His remarks were contradicted by Brian Dunn of the BMA, who said that if anyone found themselves in such a situation, they should call an ambulance immediately.

Wherever Iris Robinson is treated now, it should be in a psychiatric unit far from Northern Ireland.

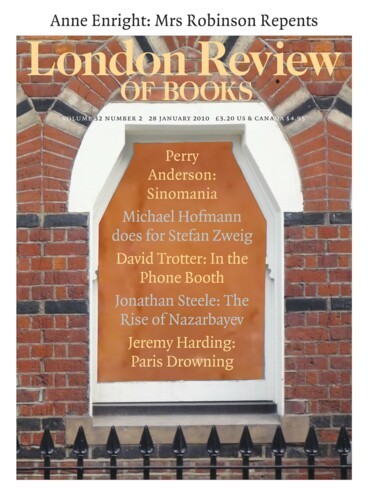

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.