In the year 400 a ‘swaying multitude’ attended the funeral of Fabiola, a Roman matron. Everyone in the crowd lining streets and rooftops was ‘flattering himself that he had a share in the glory of her penitence’. Saint Jerome’s letter to Oceanus on the death of Fabiola, the primary source of details about her life and death, tells of tribulations: her marriage (to ‘a man of such heinous vices that even a prostitute or a common slave could not have put up with them’), her divorce, her remarriage and consequent exclusion from the Christian congregation. A penitent, ‘restored to communion before the eyes of the church’, she sold her considerable property for the benefit of the poor. She nursed people with disgusting diseases, unlike the ‘many wealthy and devout persons who by reason of their weak stomachs carry on this work of mercy by the agency of others, and show mercy with the purse not with the hand’. She is, the Catholic Encyclopaedia says, a patron of difficult marriages, divorced people, victims of abuse, victims of adultery, victims of unfaithfulness, nurses and widows.

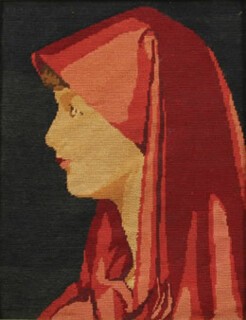

She entered the modern popular imagination in the novel Fabiola, or the Church of the Catacombs by Cardinal Wiseman, published in 1854. A sentimental story that became a bestseller and bears little resemblance to the life described by Jerome, it was intended as a contribution to the mid-19th-century Protestant/Catholic controversy in England. The novel is a more likely reason for the French academic painter Jean-Jacques Henner to have turned to the subject than Jerome’s letter. Henner exhibited his Fabiola in the Salon of 1885 (its present whereabouts are unknown). It shows a woman’s head, covered by a red shawl, in profile. Fourteen years earlier, in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War, Henner’s picture of a young woman in black peasant costume, L’Alsace, Elle attend, had become a patriotic icon. Both it and Fabiola were much reproduced.

In the early 1990s the Belgian architect-turned-artist Francis Alÿs – he was by then living in Mexico City – began to collect handmade pictures. He looked to find copies of old masters in flea markets and thrift shops. Millet’s Angelus and Leonardo’s Last Supper – the sort of thing he expected – were thin on the ground. Instead he found many versions of Henner’s Fabiola. He began to collect just those. By 1994 he was able to display 28 Fabiolas at a venue in Mexico City. The collecting continued: there are 273 entries in the catalogue of the Fabiolas currently hanging four and five deep on the walls of two rooms in the National Portrait Gallery. They can be seen there until 20 September.

The collection is mainly of pictures by amateurs. Most are oil paintings but there are enamels, a wood carving in low relief, a mosaic done in seeds, a relief in painted plaster, and painted ceramics. They are quite small – some of the pendants and brooches very small. They are all professionally described in the catalogue – size, medium, condition and purchase price. In addition to the 273 main entries there are 26 in which the pictures are described as ‘Fake, 1997’. That was the year Alÿs sent 62 Fabiolas to an exhibition in Estonia. When he got them back he found that 26 were missing. Other copies had been made and substituted for them. There are other possible sources of contamination now that it is known that Alÿs collects Fabiolas. He has had to be careful that works brought to his attention have not been manufactured for the market he has inadvertently created.

Alÿs sets up events. A few years ago he produced a series of videos about London, including one in which a fox was released at night in the National Portrait Gallery and recorded by surveillance cameras as it padded, purposeful and explorative, from room to room. The Fabiola exhibition, like many of his creations, plays on the oddity of art and of the act of collecting. It is, too, about the value we put on art, the protocols that surround it, the expectations we have of it, or that our behaviour implies that we have. This exhibition comes to London from New York, where it was mounted in the Hispanic Society of America. Both there and here in London, Alÿs’s requirements – that the pictures be seen in the context of collections of old-master paintings, and that they be fully catalogued – have been met.

The display is of the kind that points up small differences: something that was once common in natural history museums (cases of fossils of the same creature, of specimens of the same insect species) and in other study collections (the V&A’s teapots, the Folger Library’s First Folios, the BM’s runs of Rembrandt etchings). Connoisseurship makes small differences into big issues: a test of authenticity or evidence of a historical sequence.

The Fabiolas, all copies of the same picture, or copies of copies, or copies of reproductions, encourage such connoisseur-like concentration. But to different ends. There is no search here for authenticity or order; one is not, for example, trying to decide just what the lost painting looked like. Old postcards (there are a couple of these in the catalogue) would do that job better. Instead, differences cast light not on what is common, but on what is unique. To ask which of these pictures are good is irrelevant. Like participants in an Elvis lookalike competition, they betray their failure to be the original by a slightly redder lip, a smaller chin, a harder mouth. They show how very small changes in proportion, shading and outline create different characters: some images, like 010, are close to reproductions of Henner’s original. Others look like her plainer sister, some are intense (041 seems to be frowning), some look much older. In 049 her dark hair has been made blonde and her brown eyes blue. In this version there is much of the starlet and little of the saint about her. The variations put you in the presence of a crowd – that of the makers. It may be that Henner’s image was chosen as a source because the face fitted some common notion of beauty. It may also have been chosen because it offered those who acquired the images comfort in tribulation (divorce, widowhood), or an image of virtue. In its role as a religious icon, uniqueness – handmade individuality – would seem to be important. An icon is both an image and an affective object. Scratches picked up along the way are not blemishes but a confirmation of identity: the quality of the representation is less relevant than feelings about the object.

To show the Fabiolas together is to emphasise oddities. Professional copyists would have arrived at something more like the mindless correctness of a photograph. Behind each image one can imagine a personal convention of what makes a beautiful face, or a particular inability (to get the mouth right, say), that has transformed Henner’s idea of saintly good looks. It is not only Burne Jones’s faces, or Leonardo’s or Botticelli’s that are all of one kind. To be an amateur is not to be without a style.

Alÿs heightens awareness of the oddity of art. His presentation sets up ‘bad’ copies from the flea market as a crowd of witnesses whose testimony challenges the assumptions – institutional, academic, personal, critical – that privilege ‘good’ pictures in galleries. The display of the Fabiola pictures is a skirmish in a guerrilla campaign, a war game that has been running at least since Duchamp first showed a readymade. That this one (and many others) takes place within the walls of one of the institutions whose footing is in the world they challenge is all part of the game.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.