From 1 to 22 September the two floors of the Victoria Miro gallery in Islington – warehouse-like both in scale and in finish – were the site of installations by the American artist Sarah Sze. They were gathered under two titles: A Certain Slant and Tilting Planet. She has recently shown in Sweden and, over the last ten years, in America, Germany and France as well as in Britain.

Sze’s is an art of arrangement. At first glance, across the wide floors of the gallery, these installations suggest models of cities dominated by high downtown buildings and surrounded by sprawling suburbs, or of landscapes where mountains slope down to a plain. The largest pieces spread out from the corners as though they had been swept there by the eddies of a strong wind. As you get closer, things fall into legible patterns, rather as the grid of streets and meanders of a river do on the descent to a city airport. It is on this scale, on the closer view, that the imaginative ingenuity with which Sze transforms the commonplace objects she orders into stacks, lines and arrays becomes apparent.

Here are a few of the things she gathers together: alligator clips, large and small; a spiral of solder; wood screws, bright and new, standing on their heads in a military rectangle; stone chippings; polished pebbles; a scrunched-up pair of jeans. A pendulum in the form of a plumb bob, suspended from the rafters of the upper gallery, hangs, through an opening in the floor, down into the lower one. As it swings, the pointed tip of the bob cuts a shallow saucer shape out of something white: salt, perhaps (there is a lot of salt about), or wax. A yellow pen, less controlled than the plumb bob, wanders over a piece of paper that is blown about, from time to time, by a fan. The pen goes on trying to write. Plastic bottles, cut through obliquely, seem to float on the floor, as though the missing part was immersed in the concrete. Squared up lumber and neat lengths cut from twigs and slender boughs, each a few inches long, spread out, decreasing in girth and height, as they move towards the periphery of the piece. There is a box cutter and a leather punch. There are bricks and spools of thread and neatly folded towels. Lights and lamps pick out one set-up from the next. Little white paper trays that look like the insides of matchboxes are scattered about. Large balls of coloured string provide the material for guy-ropes. One length of orange cord is attached to a brick which rests on a blue pillow. Sheets of paper arranged in a trail have holes burned into them. Shiny tweezers and scissors sit side by side. At first it all seems a muddle. When you look closer and longer you become aware that everything is delicate, precise and in some inexplicable way purposeful. You carefully step over a streak of red powder and become fearful for the safety of a construction in thin balsawood rods. The vulnerability of things makes you protective. Fragile items are commonly sequestered in cases or put behind ropes. When they are exposed, trust breeds care.

Ordered cities have always, doubtless, been more of a dream than a reality. But we do, at the very least, live with the illusion that the world is more layered, has more kinds of building juxtaposed, more messages overlaid, than was once the case. It certainly seems that commonplace mysteries – what goes on there? what is that for? what made that mark? – proliferate. Sze’s work offers arrangements of unexplained significance which mimic confused reality and to a degree reconcile one to it. Where minimalism is epigrammatic and shows that a pail of water or a piece of string, rightly placed and labelled, is art, Sze is discursive. Looking for something like her work in real life I think of workshops where tools are neatly assembled in racks and on hooks, and where things made with them stand among discarded scraps of the stuff they were made from. Also brought to mind are old-fashioned displays in museums of natural history where several nearly identical bugs or bones are arranged in rows. In all these cases you don’t so much look at what’s in front of you as read it. The art of arrangement is the one that brings exhibition curators into conversation with those whose work they display; and, as Sze’s installations show, it is an art that shows its essence best in the laying out of everyday things.

What makes her work charming and engrossing becomes clearer when you consider the place of arrangement and ordering in art and in life. A well-made woodpile, a drawer of neatly folded clothes, rows of jars and tins in a cupboard: these are examples of the arts of arrangement in its primitive form. Like the most intellectual of arrangements (the periodic table, say), they are explanatory as well as orderly. They tell you how many pairs of clean knickers you have and whether you are out of pepper. The higher arts of arrangement – weaving, for example (Sze has a square of woven twigs), or letterpress printing – take existing materials (thread, types) and make them into something more just by juxtaposition. Moulding and carving reshape material. Painting and drawing set up arguments with the surface they transform. Arrangement makes things eloquent without interfering with their substance.

In Sze’s case the effect of what she makes cannot be separated from the spaces they are made in. In an alcove in the upper gallery there is an assemblage dominated by an array of paint samples that includes the whole bland palette of house decoration: ‘spice beige’ lies next to ‘sandman’. Sunlight falls on it all. You are somehow made to feel that this corner holds the answer to a question you cannot put into words. In one sense, no work could be less overtly commercial – there are no casts to take away – and even if you bought the building and its contents, the inherent ephemerality of some materials would deny long possession. But it is also, somehow, shop-like; for what do shopkeepers do if not, as this work does, open up the channels of desire?

The art of selling is setting out a stall – it applies as much to fruit and fish as it does to diamonds and handbags – so that others are persuaded to buy. The trays, drawers, vitrines, pegs, hooks and dishes that determine the rhythm of things and decisions about complementary combinations are part of a conversation window dressers and shopkeepers have with the unarticulated or at least unspoken desires of buyers. Their resolution lies in their purses. Sze presents something analogous but also ephemeral, which, like a stage performance, exists only in a narrow slice of time. The answer it asks for is attention.

One patch of floor was sprinkled with white powder (salt? flour?) while rectangular objects, now removed, were standing on it. You can see their negative shapes, just as a car, driven off after snowfall, leaves a dark memory in the place where it stood, or a kneading bowl leaves a memory in the flour on a kitchen table. Sze’s works, like those patterns, are made for short lives.

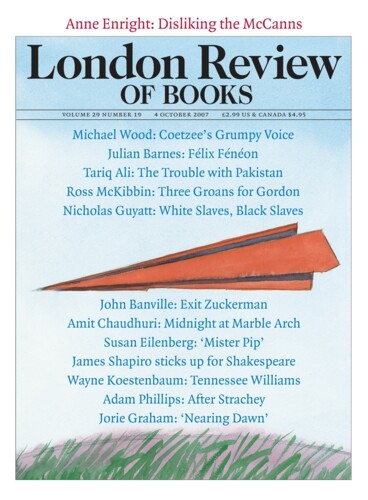

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.