In November 1913, ‘the Headingly two’, a dark-haired woman of about twenty-five and ‘a girlish figure in green cap and sports jacket’, stood trial for attempting to set fire to a football stand in Leeds. Among the evidence produced against them were some postcards, one declaring ‘No Vote, No Sport, No Peace – Fire, Destruction, Devastation’ and another addressed to Asquith: ‘We are burning for “Votes for Women”.’ It wasn’t a joke. In the last months of peacetime, suffragettes belonging to Emmeline Pankhurst’s militant organisation, the Women’s Social and Political Union, committed arson on a scale not seen since the rick-burnings of the Captain Swing riots in the 1830s. In the first seven months of 1914, a hundred buildings were set on fire, including the ancient White Kirk in East Lothian, which was totally destroyed, the refreshment room in Regent’s Park in London and houses in Liverpool and Manchester. There were other ‘outrages’, as the press called them: a railway carriage set ablaze; pillar boxes ‘fired’ with phosphorus packets which burned when exposed to air; telegraph and telephone wires cut; glass smashed in public buildings and shops. ‘Votes for Women’ was scorched in acid across golf greens in Bradford and Birmingham, and Lloyd George’s country house was attacked. In Doncaster, suffragettes tried to blow up an empty house, and a bomb went off under the Coronation Throne in Westminster Abbey; the explosion could be heard in the House of Commons.

One of the fire-raisers was Lilian Lenton, the daughter of a joiner from Leicester. She celebrated her 21st birthday by volunteering at her local WSPU office for window-breaking raids. After her first spell in prison, she graduated to arson, vowing to burn two empty buildings a week. She was arrested for setting fire to the orchid house and pavilion at Kew, went on hunger strike in prison, and was force-fed. (Kitty Marion, who set fire to the grandstand at Hurst Park racecourse, was force-fed nearly two hundred times in prison.)

Not all of those in Jill Liddington’s account of the militant years were rebel ‘girls’ – except metaphorically. Leonora Cohen, for instance, was nearly forty when she hurled an iron bar (filed down from a domestic fire-grate) at a display case in the Jewel Room at the Tower of London. Unlike Lenton, Mrs Cohen was a respectable married woman, the wife of a staunchly Liberal watchmaker in Leeds. Until she became branch secretary in 1911, she had contented herself with bringing up her son, and selling newspapers and making marmalade for the WSPU. When Asquith suddenly announced a man-only suffrage bill in November of that year, reneging yet again on a commitment to women, she turned to direct action. Her subsequent hunger strikes, and refusal to accept fluids, in Armley jail in Leeds nearly killed her. After her husband bombarded the Home Office with furious letters condemning the barbarity of her treatment, she was released under the notorious Cat and Mouse Act, passed in the summer of 1913. Hunger-strikers could now be sent home to recover and clawed back into prison once they were well enough to continue their sentences. Eventually, the Cohens were persuaded to retreat to Harrogate, where Leonora set up a guesthouse for WSPU sympathisers and offered ‘reform diets’ of vegetarian meals and salads. She sheltered Lilian Lenton when Lenton violated her parole and helped her to escape a police cordon dressed in her son’s Norfolk suit and cap. Lenton was one of many suffragette fugitives who remained in hiding until the war brought them amnesty.

Like their feminist forebears, suffrage historians have tended to take sides, for or against militancy. Jill Liddington’s influential first book, One Hand Tied behind Us, written with Jill Norris, and published in 1978, offered a corrective to ‘virtually all the books on the subject’ which told the suffrage story ‘in terms of the middle-class, London-based leaders’. Liddington and Norris uncovered a new group of women whom they called ‘radical suffragists’ and who lived and worked in the North of England, the cradle of the movement. Like the remarkable Selina Cooper, a Lancashire mill-girl from ‘Red’ Nelson, whose biography Liddington has also written, these women canvassed for the vote at the factory gate and on doorsteps, especially in the cotton towns of Lancashire. Nurtured by the Labour movement and active as trade unionists, the textile and factory workers were the only group of women with serious political clout. Some of them, like Cooper, became paid organisers for their local suffrage societies under the aegis of Millicent Fawcett’s non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies; but all continued to work through existing organisations, refusing to isolate themselves from other political campaigns. They saw universal female suffrage as one element in a full programme of measures to improve women’s lives – equal pay, birth control and child allowances. One Hand Tied behind Us was ‘people’s history’ of the most effective and original kind. In retrieving the lives of those who had disappeared from the historical record, it transformed our idea of the suffrage movement and made the histories that had concentrated on Westminster look parochial.

Rebel Girls is different. Its remit is broader and its constituency more mixed. Like Liddington’s earlier work, it is a close, local study but the focus has shifted from Lancashire to Yorkshire and to the later years of suffrage in the 1900s. Clothing and millworkers in towns like Huddersfield and Halifax had far less to do with the law-abiding NUWSS than their Lancashire sisters, whose genteel leadership was strongly associated with the Liberal Party and employers. They tended to form branches of the WSPU instead, although membership of the different suffrage associations was by no means hard and fast. ‘Community suffragettes’ might well give up on peaceful protest and take radical action when sufficiently frustrated with the government. Factory workers were suffragettes and hunger-strikers, but so too were housekeepers, typists, shop assistants and teachers, as Liddington’s scrutiny of charge sheets reveals.

Many of the fifty or so women in Liddington’s impressive biographical appendix are newcomers to suffrage history. A handful belonged to the Suffragette Fellowship after the war and corresponded with each other, or left their papers; some wrote memoirs and Liddington has come across descendants who add their reminiscences. A few, such as Leonora Cohen, who lived to 105, were rediscovered by the women’s movement in the 1970s. But mostly she has started from scratch, scouring local record offices and libraries, trawling through newspapers and the literature of the suffrage societies, poring over court cases and Home Office files. As with all empirical research, much is serendipitous. Huddersfield looms large thanks to the lucky find of a minute-book which gives a blow-by-blow account of rifts in the local branch.

Although often only a fleeting reference to an individual survives, the merest details can be the most suggestive. Why did Alice Noble from Leeds, the daughter of a brick-maker, working as a domestic servant, join the militant protests in London in spring 1907? She was imprisoned in Holloway, aged 16. Or Lizzie Berkley, aged 23, a ‘fustian-clothing machinist’ from Hebden Bridge, known as ‘Fustianopolis’, one of the women who battled with five hundred policemen lined up to stop them getting near the House of Commons that March? Of the 75 women arrested, a good quarter were from the West Riding. Lizzie got 14 days in Holloway. What did imprisonment do to their lives? And what of the stalwarts of the NUWSS, like Agnes Sunley, the wife of a packer in an asbestos factory, who’d canvassed for the vote in working-class districts of Leeds since the 1880s? Her death certificate in 1924 records that she died in her seventies ‘of exhaustion’.

What struck me most was how much suffragists from different societies had in common. They were all galvanised by the new and exciting world of politics and, at least to begin with, had the time of their lives. As for so many generations of radicals, politics was their open university, their route to ‘self-development’. Annie Kenney, a mill-girl from Oldham who was more or less adopted by Emmeline Pankhurst, remembered recruiting for the WSPU in Pennine moorland and villages where women were ‘versed in Labour politics’: ‘The lamp would be burning, and we would talk about politics, Labour questions, Emerson, Ruskin, Edward Carpenter, right into the night.’ Nellie Gawthorpe was another who thrived in this atmosphere. Brought up in the working-class respectability of a red-brick terrace in north Leeds, she was transformed by the discussions held at her local Pupil Teachers’ Centre and began to haunt the Leeds Art Club’s conversazioni, where such topics as ‘Art and Democracy’ were debated. Nellie rechristened herself ‘Mary’, which must have sounded less plebeian, and became one of the chief organisers of the WSPU. Sent on a trip to ‘rouse Sheffield’, she bought her first pair of sandals and found herself in Edward Carpenter’s house, having to repulse the advances of another elderly fruitarian simple-lifer. Class-barriers were overturned when Gawthorpe sat down with members of the London leadership to listen to Cecil Sharp’s folk songs.

Edith Key, president of the Huddersfield branch of the WSPU, was also reborn. The illegitimate child of a domestic servant, she was working as a knotter, preparing thread for the looms, when she joined the Huddersfield Choral Society. There she met her husband, a blind musician who had toured Europe before finding socialism; he set up a music shop and they began to attend open-air meetings of the Independent Labour Party. They called their son Lancelot, presumably after Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. Other women served a literary apprenticeship in the suffrage movement. Lavena Saltonstall, another of Liddington’s discoveries, a ‘tailoress-turned-weaver-cum-writer’, made her debut on the letters page of the Hebden Bridge Times. After her time in Holloway, she became known as ‘Lavena, the Modern Martyr’, contributed a regular column to the Halifax Labour News and wrote a series, ‘Letters of a Tailoress’, for the magazine of the newly founded Workers’ Education Association.

Liddington touches on the satisfactions, erotic and otherwise, of the bonds forged between women, sometimes across the social divide. The most intense communion existed between ex-prisoners, who frequently lost all of their former friends. Liddington comments on the contrast between the highmindedness and lofty prose of some testimonies and the oddly jejune tone of others: ‘I was feeling rather whizzy,’ Mary Gawthorpe told a friend, as she sat in the Black Maria about to drive off to prison. But both the exalted rhetoric and the schoolgirl slang capture the romance of politics, which could make running a branch meeting as rapturous an experience as being arrested. Molly Morris apparently found setting fire to pillar boxes a lark, recalling ‘the little troublemakers’ she hid in her handbag ‘ready for posting’. She left the WSPU when the older women disapproved of her socialist men friends hanging around. Flibbertigibbet though she was, she eventually married a Marxist, Jack Murphy, went off to Moscow with him and joined the newly formed British Communist Party after the war.

The suffragists borrowed much of their agitational apparatus from the Labour movement – open-air meetings, banners, marches, brass bands, hymn-singing, petitions and handbills – but they represented a new breed of national campaigner. Devotees of railway timetables, organisers hopped on and off trains, or found themselves ‘racing round the constituency for by-elections’, often holding two or three meetings an evening. Cicely Corbett, an activist with the supposedly more sedate NUWSS, was ‘so caught up in hectic campaigning that she seldom slept in the same bed twice’. In 1908, the NUWSS took to the open road in a horse-drawn caravan which toured the whole of Yorkshire (scribbled postcards help Liddington track their route). Ray Costelloe, later Strachey, who published her own history of the fight for suffrage, The Cause, found ‘vanning’ a great buzz: ‘All the way through beautiful old villages we distributed leaflets and did house to house visiting, so that we were constantly on the go, constantly talking and arguing.’ The physical emancipation was thrilling. Wearing practical clothes – a greatcoat, shirt and tie – or cooking and washing out of doors was as liberating as taking to the streets for the first time.

The WSPU’s militant campaign took off in autumn 1905, when Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst, Mrs Pankhurst’s oldest daughter and strategist, were ejected from a Liberal rally at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester for heckling Sir Edward Grey. Christabel deliberately spat in the face of a policeman in order to get arrested. Her imprisonment made the national headlines and the WSPU was accused of courting publicity (‘suffragette’ was a patronising term coined by the Daily Mail). But all the suffragists went in for advertisement, selling their papers on the streets, publicising meetings in the press: they could not otherwise have orchestrated regional, let alone national campaigns. Photography and film made everyone more image-conscious. Christabel knew what the impact would be when Annie Kenney appeared on platforms in her shawl and pattens. The huge suffrage processions were marvellous photo opportunities, as well as displaying the societies’ formidable organisational skills. In June 1911, the last time all the suffrage groups presented a united front, forty thousand women, including seven hundred prisoners or their proxies dressed in white, walked for seven miles of ‘gold and glitter and sparkling pageantry’ with a panoply of new banners and pennants held aloft. The suffrage societies sold sashes and ribbons in their own colours, and branded groceries, playing cards, brooches, tea-sets and other sundries. Businesses cashed in. Oxford Street stores did a nice line in lace blouses with ‘Votes for Women’ cunningly embroidered into their yokes. Suffrage campaigning was not just a new way of earning a living: politics encroached on everything from fashion to food. For the militant it could become a complete social identity. Vegetarianism, for instance, seemed a logical protest against the materialism of Edwardian patriarchy.

Dedication was second nature to those trained in Victorian ideals of self-sacrifice, and Rebel Girls provides many instances of women who found a stronger sense of themselves in self-denial. Elizabeth Pinnance, a rug-weaver from Huddersfield, was another who did time in Holloway in 1907. On the sitting-room wall of her granddaughter’s neat suburban home, an illuminated testimonial presented to her by Mrs Pankhurst is still proudly displayed, with its tribute to Pinnance’s ‘self-forgetfulness and self-conquest’. All the suffrage groups had recourse to older ideas of womanliness and were touched by the social purity movement: prisoners suffered humiliation to ‘uplift their sex’. St Joan was a favourite example for both the WSPU and NUWSS. The ultimate form of self-denial was self-starvation. Women who went on hunger strike felt on a par with saints and mystics, able to transcend their sexual bodies and demonstrate the spiritual superiority of women in their disregard for the flesh.

Demonstrators were shocked but also energised by the misogynist insults and rough treatment they received from the police, who carried them upside down, with their skirts over their heads, squeezed and pinched their breasts, kicked and punched them in the stomach. When Marion Wallace Dunlop began the first ever hunger strike in a British prison in 1909 she was protesting at being treated like a criminal and not as a political prisoner like the Irish rebels. The introduction of forcible feeding (again for the first time in Britain) turned the women’s bodies into a battleground as well as a weapon against government aggression. Since Parliament did not represent them, law-breaking was seen by the militants as a response to tyranny. In words that are now very familiar, suffragettes in court demanded to be tried by their peers and refused to recognise the legality of the proceedings or the jurisdiction of the judges. Prison radicalised many still further. Laura Wilson, a worsted-coating weaver from Halifax told a reporter: ‘I went to jail a rebel, but I have come out a regular terror.’

Despite the ground it shared with other suffrage organisations, and despite its male supporters, the WSPU was unique as a separatist organisation. Eventually, it opposed every candidate in general as well as local elections, regardless of party, unless they put female emancipation at the top of the agenda. The suffragettes went on demonstrations expecting to be arrested and into prison expecting to go on hunger strike. Repeating the same tactics was the point: protest mattered more than negotiation. In 1913, Mrs Fawcett dissociated herself publicly from the use of physical force by the government and by the suffragettes. The sado-masochistic imagery of predator and victim in the WSPU ‘Cat and Mouse’ posters, which showed a suffragette mouse swooning in the tomcat’s mouth, made many suffragists uneasy. Male power was increasingly denounced by militants not only in connection with the protectionism of the unions or the chauvinism of the professions, but in terms of sexual power, the violence said to be inherent in masculinity itself. There is a direct lineage from Christabel Pankhurst’s warnings against the injurious nature of sexual intercourse for women to those radical feminists of the 1970s who saw little to choose between heterosexual penetration and rape.

The question of who became a militant, and why, is hard to answer. To judge by Liddington’s evidence, it was as much as anything else a matter of where you lived and whether there was a meeting in your district. No profile of a typical militant emerges; political allegiances seem chancy. This is in part a consequence of Liddington’s biographical approach: biography uncovers multiple motivations; it individualises and specifies. When other ‘suffrage detectives’, as Liddington calls them, begin to follow her lead, it should be easier to gauge how representative her Yorkshire constituency is.

This is perhaps the first book to recognise that an entire generation of young women, born between 1881 and 1891, grew up with ‘Votes for Women’ ringing in their ears. Liddington is cagey about using their autobiographies, even when not overtly propagandist. One of her best finds is another Pankhurst, Adela, the third and youngest daughter. She became chief organiser for the Sheffield WSPU and ‘ran the North’. At the age of 19 she was mesmerising a crowd of 100,000 people in Leeds – speaking for an hour and a half. Her memoirs, written years later, tell a sorry tale of neglect by the family and then being ‘got rid of’, perhaps because she was too left-wing or too good a speaker: Christabel did not want any rivals. Adela was shunted into agricultural college and eventually put on a boat to Australia, the fare paid by her mother. Complaining bitterly of ‘the family attitude (Cause First and human relations nowhere!)’, she took up a pro-family position after the war, as her mother did, lambasting Bolshevism and strikes. Adela was that new phenomenon: the politicised child, formed within the church militant of suffrage and socialism. Her apostasy is representative of that of many others whose adolescence coincided with the peak of their political commitment. ‘Experiments are dangerous things,’ she wrote.

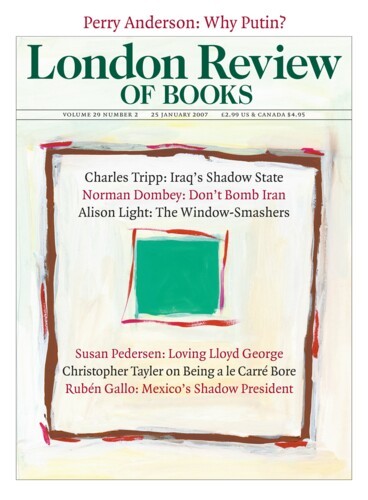

One of the most poignant stories is that of Dora Thewlis, the quintessential rebel girl. She too had been brought up in progressive politics by her mother, and in 1907 at the age of 16, travelled down to London on the WSPU trains with the ‘clog and shawl’ brigade and joined in the clashes with the police. Had up in court, she was told by the magistrate that she ought to be at school. He obviously had no idea that where she came from girls went halftime into the weaving sheds at the age of 11. She was already earning a pound a week and considered herself a worker with rights. Dubbing her ‘the Baby Suffragette’, the Daily Mirror splashed the photograph of her arrest across its front page (Liddington reproduces it as her cover), her shawl adrift and her hair and skirt undone, shouting and struggling in the clutches of burly and impassive policemen. This image was then sold on a postcard entitled, with the cavalier ignorance of southerners: ‘A Lancashire Lass’. Prison proved too much for Dora and back home in Yorkshire she continued to talk to the press about her ‘torture’. Meanwhile her mother received a chilly letter from the local WSPU branch, asking them both to resign. Were they seen, Liddington wonders, as ‘publicity-hungry egoists’? Just before the war Dora sailed to Australia, and became a blanket-weaver near Melbourne, an early casualty of celebrity culture and a political scapegoat.

Liddington laments the fact that these stories, full of incident and crisis, upstage the plain tales of the more peaceful democratic suffragists. The WSPU certainly had plenty of ‘dash and go’, but I’m surprised that she should think ‘contemporary readers now feel tolerant towards suffragette window-smashers and attackers of pillar boxes,’ because the vote was eventually won and no innocent bystanders got hurt. Militancy is hardly an uncontroversial subject. ‘Give us the Vote or give us death’ was the WSPU’s final slogan and in these years artists, writers and politicians across Europe looked to the redemptive power of the blood sacrifice. When Emily Davison died trying to grab the bridle of the king’s horse on Derby Day 1913, she was given a hero’s send-off, with suffragettes saluting her coffin on the steps of St George’s, Bloomsbury. Much of the press coverage was respectful, awed by her devotion to ‘the Cause’.

Rebel Girls wants to counter ‘celebrity suffrage’ by finding out more about local suffragettes. It’s an uphill task. Not least because the WSPU became effectively a paramilitary organisation and members did what the leadership told them. The Pankhursts had already cancelled a conference on ‘internal democracy’ in 1907 and had publicly torn up a draft constitution. Five years later, Emmeline Pankhurst expelled half the WSPU leadership, among them old friends and generous backers. She became both treasurer and leader of ‘the Union’, with Christabel directing policy. Lenton and Cohen may have been acting under their own steam but they had been fired up by Mrs Pankhurst’s inflammatory rhetoric and open incitements to violence. Though she insisted that targeted buildings should be empty and life was sacrosanct, she gave public blessing to ‘guerrilla warfare’, telling WSPU members that to refrain from militancy was itself a crime. Sixty years later, Leonora Cohen still remembered that she had not wanted to let Mrs Pankhurst down. What Liddington calls the ‘historic heroism’ of her rebel girls meant being loyal cadres as much as ‘lone mavericks’.

Though Rebel Girls is more sympathetic to the militants than her earlier work, Liddington still believes that they did more harm than good. The WSPU can certainly take some of the dubious credit for expanding the language and practice of political sectarianism in Britain. As their membership contracted to hardcore zealots who felt more and more persecuted, social righteousness soon shaded into self-righteousness; accusations of heresy began to be made, and there was talk of betrayal, expulsion and proscription, and of cutting out ‘the dead wood’ in order to revive the movement. By the summer of 1913, Mrs Pankhurst was going to meetings accompanied by an armed bodyguard of women who rhythmically swung Indian clubs and batons to protect her from arrest. Stages were draped with barbed wire. A year after the war began she was denouncing members of the WSPU, even former hunger-strikers, who showed ‘pro-German sympathies’ in the crowd of women she now urged to war service. Much more needs to be written about what Teresa Billington-Greig, a disaffected militant, called the ‘double shuffle’ between victimhood and violence.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.