The government’s reluctance to allow intercept evidence to be used in court to procure the conviction of terrorist suspects seems mysterious and self-defeating: why deny yourself such a key weapon in the ‘war against terror’, especially if there are ‘several hundred’ terrorists already in this country planning attacks, as the prime minister has recently claimed?

Until 1985, the interception of communications by the state was wholly outside the law. The official position was that such eavesdropping took place only on the authority of a warrant issued by the secretary of state when it was needed for the detection of serious crime or for safeguarding the security of the state. Even then, various other procedural hurdles had (supposedly) to be negotiated. But there was no mechanism for ensuring that the state stayed within its own rules, and the 1970s and early 1980s were full of rumours of excess on the part of MI5, directed at CND, the trade unions (especially the NUM) as well as more obvious Cold War opponents. The purpose behind all this surveillance, in the national security arena at least, was not to build a case against suspects under the ordinary criminal law: it was pure intelligence gathering, intended to inform the advance planning of state strategists, to disrupt the operations of the other side, or to permit the effective conducting of psychological games and the playing of dirty tricks. There was never any question of using the material in court.

This approach had to change when legal regulation was forced on the authorities by a decision of the European Court of Human Rights, in the case of Malone v. United Kingdom (1985). The Interception of Communication Act 1985 that followed put the whole matter on a legal basis, setting out various criteria for lawful interceptions and providing a measure of accountability, but at the same time going to immense trouble to exclude the courts from any meaningful role in the process. Officials were worried not only about their now lawful intercepts being referred to in court, but about their continuing illegal operations being held against them. Amazingly, Section 9 of the act provided that in any proceedings before a court no evidence was to be adduced and no questions were to be asked in cross-examination which tended to suggest that an interception had taken place, with or without a warrant.

This continued insulation of surveillance from the disciplines of the criminal process was controversial almost from the start. Judges didn’t like it, particularly when terrorism came to replace Communism as the bogey-man in chief. In 1996, in a report which was otherwise sympathetic to the authorities, Lord Lloyd of Berwick called for a reform in the law to allow such evidence to be led in national security cases. Not only did the government reject this view, it re-enacted the prohibition in the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000. With the introduction of de facto internment in the aftermath of 9/11, and the subsequent WMD fiasco, agitation to change the law has gathered in intensity. The Metropolitan Police commissioner, the director of public prosecutions, the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights, the pressure group Liberty all agree – even Stella Rimington, the former head of MI5, has reportedly condemned the restriction as ‘ridiculous’. Practically every other country that has considered the issue has decided to make the material available in court if needed; nowhere is there any question of forcing the authorities to adduce such evidence. The whole debate here in recent weeks has rightly focused on the question of whether the prosecution should be free (but not compelled) to adduce such evidence – hardly the stuff of revolution.

And what of the arguments for keeping the ban? These mainly involve assertions that the material would be likely to be ruled inadmissible in court. If this is true it is important to know why. If the intercepts are too unreliable, too easily tampered with, to be usable in court – and this seems to be the point of the admissibility argument – how can they be deployed in any kind of intelligence assessment? And if they are used, even so, how can such ‘data’ (coming from the ‘experts’ who told us all about Iraqi WMD) reliably provide the basis for any action at all? And yet this is precisely the government’s plan: there are to be control orders restricting what suspected terrorists can do, whom they can meet and the contacts they can make; at some future date there might be not house arrest but internment in a government facility. All this on the basis of ‘intelligence’ gleaned maybe from proper sources, but maybe also from intercepts too unreliable to be tested in court and/or from the victims of torture by foreign security officers in other countries. The only result of the various civil libertarian ‘concessions’ wrested from the home secretary in debates on the new bill in Parliament will be to require the courts to agree all this when asked to do so by the home secretary, but without giving them the tools to do a proper procedural job.

In 1994, Stella Rimington gave the Dimbleby Lecture. It was the first time a serving über-spook had appeared in public. Boasting of MI5’s successes, she talked of the large number of ‘terrorists’ that had been apprehended and were awaiting trial. Not ‘suspected terrorists’: just ‘terrorists’. The intelligence services have never understood the need for a criminal process: their ideal world would be one in which official suspicion led straight to incarceration. This is why they so fervently oppose the idea that any of the ‘evidence’ they build up should be exposed to the rigours of a criminal trial, a process for the safeguarding of individual liberty with which they are, institutionally, profoundly out of sympathy. They must be thrilled to find a government so willing to follow their agenda. A former head of the anti-terrorist squad at Scotland Yard, George Churchill-Coleman, lamented recently that Britain was ‘sinking into a police state’. The refusal of the intelligence services to yield on the admissibility of intercept evidence, and the support they have received for this position from their political masters, is the clearest evidence we have that if this is not yet the case, it is (though they would no doubt phrase it differently) the wish of important elements in our political and security community.

Send Letters To:

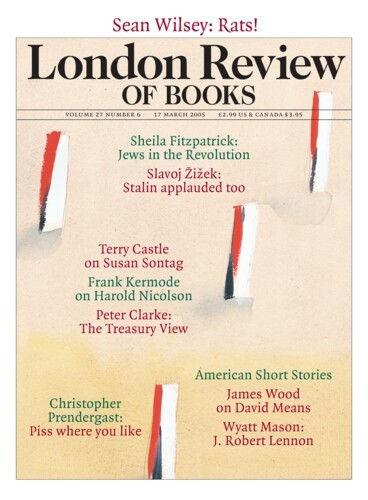

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.