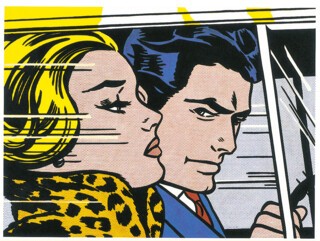

White paint and an exemplary installation currently give the Hayward Gallery an of-our-own-time presence. But the paintings by Roy Lichtenstein which line the walls – the early ones anyway – are now so well established as an ironic commentary on pop culture that they read as decoration, as conventional and period-flavoured in their way as chintz.* The general effect of the show is cool and spacious. You could be in a fashion store which has decided to go retro and jazz up the decor. To see more than decorative wit you must try to think of the moment in 1962 when Lichtenstein’s show of enlarged frames from war comics and romance comics at the Leo Castelli Gallery put out the news that another artist – he was not well known – had taken a sharp turn off the path most American high art was following.

There are pictures in the Hayward show from right up to the last year of his life – 1997. In the Bernard Jacobson Gallery in Clifford Street, W1 you can see, until 27 March, the last things he did: prints of interiors in which the usual elements are used to such bland effect that they could have been turned out by a Lichtenstein computer-graphics program. The comic-strip frames, which are still the Lichtenstein pictures one thinks of first, are not in a majority at the Hayward, and the other subjects are connected with them only by the use he made of the accidents and conventions of cheap comic-book drawing and printing – heavy outlines, flat colour and coarse mechanical screens. Among them are hard-edged drawings of big fluid brush marks – a mockery of gestural art. Or perhaps a tribute to it. There are pictures of rooms, a car tyre, an exercise book and a golf ball. Right at the end are paintings in which graded tints show hills rising out of mist with a tiny kitsch-Oriental boat or bridge in the foreground. But only by going back to the original moment – the moment when Life magazine headed an article, ‘Is He the Worst Artist in America?’ – can you imagine the force of his transgression.

As early as 1963 he hired an assistant. These are not pictures where you look for the hand of the master, or indeed any hand at all. That the early ones have a sure place in the history of American painting in the 20th century has little to do with a battle in the studio between man, paint and canvas – the painter as hero was becoming the artist as ironist.

Lichtenstein’s change of direction was of the kind which creates the illusion that art has a goal – or at least suggests that style change follows patterns. That one force draws style towards classic stillness and abstraction and another pushes it towards expressive exaggeration and storytelling. That every move away from narrative (for example, towards pure landscape or abstraction) is liable to be followed by a wander back in its direction (Surrealism, Pop). Lichtenstein can be explained either way. He used narrative material but made his comic-book frames into pictures with simple shapes and firm organisation, which some read as a kind of classicism. What seemed a radical way with narrative finished up as monumental decoration.

A tradition of illustration and cartooning runs unbroken and often unnoticed through the undergrowth of culture. Its practitioners keep full a huge image reservoir. High art, particularly over the last couple of hundred years, has regularly dipped into it. But there is a difference between Degas’s attitude to, say, Keene and Japanese prints and Lichtenstein’s to commercial art. For Degas, Keene was a great draughtsman. Lichtenstein, on the other hand, needed crude performances, not great ones. He said of the moment when he began to use commercial art to make pictures that ‘it was hard to get a painting that was despicable enough so that no one would hang it . . . it was almost acceptable to hang a dripping paint rag, everybody was accustomed to this. The one thing everyone hated was commercial art.’ But, he concluded, ‘apparently they didn’t hate that enough either.’ Rather to his surprise he found himself a success; it was years before he really believed the trick would go on working.

How was one supposed to read the early pictures like Whaam! and I know how you must feel, Brad? Were they a tribute to popular culture or a criticism of it? Were they just plagiarism? Were they failed plagiarism? In 1990, as a comment on High & Low, a show at MoMA, Art Spiegelman contributed a page of cartoons to Artforum. In the first frame the ‘thinks’ bubble attached to a Lichtenstein-like blonde who has lost half her face – the skull shows through – reads: ‘Oh Roy, your dead high art is built on dead low art!. . . The real political, sexual and formal energy in living popular culture passes you by. Maybe that’s (sob) why you’re championed by museums!’ The sheet uses the styles of cartoonists such as George Herriman (Krazy Kat) and illustrators such as Posada to remind you that your mind is as full of old drawings as of old tunes. What right has gallery art to make a meal of indifferent comic-book drawing of the kind Lichtenstein used and then ignore stuff as good as Krazy Kat?

Fair comment, or it would be if Lichtenstein’s purpose had been to be a critic. When I walked around the Hayward my first thoughts had nothing to do with low art. I was struck by how very handsome the whole thing was. Large pictures announce their provenance with authority. What each one says most clearly is: ‘This is a Lichtenstein.’ While most fashionable 20th and 21st-century paintings are badge-like in that way, there is usually a reason to stop in front of them for a while. Lichtenstein demands only brief attention. As you tour the exhibition, pausing, but not for long, and later flicking through the catalogue illustrations, the badge and the thing badged, the picture and the label, elide.

Lichtenstein’s pictures reproduce badly. It is not that their flat colours and neat dots are hard to get onto the page, but that once they are there, in the case of the early work at something like the scale of the original strip-frames, the bad art/good art tension slackens. The screen dots – themselves a comment on the physical feel of old commercial printing – no longer take on the character of abstract patterns and revert to representing tone. Seen small like that, the calmness (not to mention the irony) is squeezed out of the picture. This applies equally to the later images which are not based on printed originals. At page-size the contrast between the big dots and the tiny boats and bridges in the late misty mountain pictures is almost unreadable.

Lichtenstein’s first versions of cartoon characters – Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny – were ‘artistic’ drawings, a bit like de Kooning charcoal sketches: it was only when he dropped the personal handwriting and kept his contribution to selection, scale-change and small refinements to the slick brush-drawn lines, that the shock of the ‘truly despicable’ was felt. The comic-book pictures were not in this sense subject-matter: they were not like the paintings which Picasso made of paintings by Delacroix and Velázquez. That was more what happened later, when Lichtenstein used the comic-book style to support a different kind of transgression and made his own ‘Picassos’. (None of his pictures of pictures is in the show, although the most monumental of the later work here – Cosmology of 1978, for example – has a strong taste of Léger.) Good copying was necessary if the comic-book pictures were to work. In images he invented himself, where the lines are less energetic, you miss the tacky vitality of the brush-drawn mark. Enlargement and adjustment put quote marks round the comic-strip girls and explosions, but the life his pictures draw from run of the mill examples of the genre they parasitise makes one wonder, along with Spiegelman, whether the contribution of popular art to visual culture doesn’t deserve more attention, as well as more credit. At Flowers Central in Cork St, W1 you can see, also until 27 March, prints of collages put together in the 1960s and 1970s by Eduardo Paolozzi (he appears, incidentally, in the Spiegelman cartoon in a list of true masters of popular art). The material which Pop Art drew on is here assembled raw; the ‘despicable commercial art’ which ‘everybody hated’ is cut and pasted but not transformed. What made ‘everybody’ hate it – crassness, vulgarity, clumsiness – is alive, festering away. The real irony is that Lichtenstein’s best pictures depended on keeping alive an infection which came from their dirty origins: the more he sterilised his material the less affecting the paintings were.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.