The steeple of the church of St George, Bloomsbury is an astonishing confection. A square tower rises from the ground to above roof level. It is topped by a little pedimented temple. The temple supports a stepped pyramid and the pyramid a sacrificial altar. On the altar, like a doll on a wedding cake, is a statue of George I in Roman dress. It was paid for by Mr Huck, brewer to the royal household. The lion and unicorn from the royal arms once played around the base of the pyramid: they were finally removed in a dilapidated state during G.E. Street’s renovation of 1871 – he was probably embarrassed by them in any case. Funds permitting, current restoration work will see them back in place, newly carved.

From the windows of the LRB offices in Little Russell Street we can see much of the church and all of the tower: it rises above the plane trees and the 19th-century vestry house which partly obscure the formidable, blackened north wall of the church. The steeple is both wonderful and absurd, an archaeological speculation tuned to resonate with the drumbeats of Hawksmoor’s hefty keystones and round-arched windows. The temple, pyramid and altar are based on Pliny’s description of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. The temple, like a bugle call, announces the theme repeated on a larger scale on the south front. There, you find a portico with six Corinthian columns, a wide flight of steps, a porch and a pediment, all in good Roman style – the model this time was one of the temples at Baalbek. The surrounding buildings are higher than they were when the church was built, but King George shows clear above the roof line, just as he does in Hogarth’s Gin Lane. All in all, the design of the church is majestic – original, strange and energetic. But from the office window we could see that weeds had found a foothold in the stonework: it was as though the church was feeling its way towards becoming a Piranesian ruin. This was not to be allowed.

People climbing round the roof, tapping and measuring, were the first sign that restoration was in hand. Then there was the removal of the cadavers. For weeks, a barrier of black plastic sheeting hid the entrance to the vaulted space which runs under the church. We heard quite accidentally – the transfer was done with proper discretion – that bodies were being taken out. A few would have seemed unlikely enough: the actual total of eight hundred was astonishing. The news took on a grim colour from the dark presence of the building; stories of plague pits came to mind. But it turned out that there was no mystery, no sinister revelation to give weight to Peter Ackroyd’s appropriation of Hawksmoor’s buildings as stages for the malevolent and occult. Although the burials had been decent and officially sanctioned, the bodies were there contrary to the intentions of the Commissioners appointed under an Act of 1711 to oversee the building of ‘50 new churches of stone and other proper materials’: they had been advised by both Wren and Vanbrugh that no burials should take place in or around the new buildings.

It was only in 1804 that coffins had begun to pile up. Colin Kerr, the architect overseeing the restoration, explained that the last coffins must have gone in before the Act of 1856 which forbade church burials. The vault was then bricked up. When it was opened, many bodies were found still to be well housed. Most of the coffins had stood the test of time; they were stoutly made: an inner wood coffin was enclosed in a lead-lined outer one and the whole wrapped in studded leather. The contents of those which had mouldered and were in danger of spilling were examined by archaeologists from Oxford. All were transferred with proper ceremony to a burial ground in North London. What can be learned from 200-year-old bones? Perhaps something about top of the range 18th and 19th-century dentistry. Kerr cited evidence of the insertion of false hardwood teeth, and of ‘Waterloo’ teeth – real ones plucked from the dead on the battlefield. These were not paupers.

The building itself hasn’t survived unscathed. Over time, sulphurous rain falls. It washes exposed areas clean, but where it gathers on horizontal or sheltered surfaces it tends to dissolve the stone and redeposit it in grimy, calcareous accretions. The effect London weather has on Portland stone is to some eyes very handsome, as became clear in the arguments fifty years ago about how much grime to wash off St Paul’s. The contrast on a bright day between the dirty-grey south portico of St George’s, which was cleaned decades ago, and the stark black and white of the untouched south face of the tower suggests that the clear picture one now has of the portico’s crisply carved Corinthian capitals came at a price. Kerr intends to do as little as possible to the outside of the building – essentially, to pick off the accretion of black scabs and wash off muck. St George’s will still look like an old building: there is no suggestion that it should be given a course of architectural Botox.

While rain slowly melts the stones, gravity, with equal slowness, pulls the building down. The heavy tower presses hard on its foundations. It was built last and has sunk slightly deeper than the west wall it stands beside. (All over London, speeded up by clay shrinking after a dry summer, the front bays and rear extensions of Edwardian terrace houses are shuffling about in much the same way.) Meanwhile, arches push at their abutments. They spread, a voussoir rotates through a fraction of a degree and the centre of the arch drops a millimetre or so. Sinclair Thompson, the engineer who surveyed the church, takes the long view. If movement is ancient, very gradual and not accelerating, heroic measures – tie bars, underpinning – are not even considered. The good news is that St George’s is remarkably sound. It was beautifully and solidly built in stone, inside and out. I had misread the painted and gilded columns, capitals and entablature which dominate the interior as plasterwork. In fact, they are solid stone, like the walls. Or more or less solid: one thing that the structural survey showed was that some walls have a well-laid brick core. In one way the solidity is not surprising: St George’s was 15 years in the building, and expensive. The estimate for the construction of the church and a house for the minister was £9790 17s 4d, the final cost £31,000.

The restoration required on the outside (the lion and unicorn apart) is necessary to defeat the effects of time and weather: inside there is the further task of selectively undoing refurbishments and alterations which adapted the church to changes in the needs and taste of priest and congregation. It is Hawksmoor’s reputation which attracts the funds needed for restoration, and quite radical changes which will make the inside more the way it was when he left it are contemplated.

The alterations made inside St George’s over the last three centuries were driven by practical as well as aesthetic agendas. To understand what has been done and why – and to judge what could best be done now – you must start with the specifications put together by the Commissioners of 1711. The Act responded to a need: London was expanding, and short of churches. The problem was how to find seats for willing congregations not, as now, how to fill pews. The 1711 Act was also a political gesture: a High Church, Tory celebration of power regained. In 1715 the Whigs were back in office and new Commissioners were appointed, but some of the churches were already being built and the scheme could not be scuppered. Besides, churches were still needed. In the end, 12 of the 50 were built, six to designs by Hawksmoor.

Hawksmoor’s designs are close to the style of church Vanbrugh advised the Commissioners to go for: one which gave ‘the most solemn and Awful appearance both within and without’. Wren was more practical: he included useful remarks about sites and materials, and suggested his own St James Piccadilly as a good, economical model. But the two architects agreed on many things, in particular that the new churches should stand free and not be crammed into the tight, built-up corners many City churches occupy.

On the whole the Commissioners followed the architects’ suggestions. They specified free-standing churches within churchyards; porticos at the west end; a parish room and vestries; and towers with spires. They also set out liturgical requirements: a true east orientation, a raised altar approached by three steps, a font large enough to allow infant baptism by dipping, and low pews – ‘single and of equal height so that every person in them may be seen either kneeling or standing’.

A letter the Reverend George Hickes submitted to one of the Commissioners – ‘Observations on Mr Vanbruggs Proposals about building the new churches’ – gives a good idea of the kind of ecclesiastical advice they received. The tone is one a conservative cleric might assume today in a letter to the Times. Hickes advocates the tried forms and has a sharp eye for potentially improper goings-on in the pews – there should be no hiding places in the new churches. His tone is severe. Modern architects, he says, have used church designs to ‘show their skill, and get themselves a name particularly. It is to be hoped that they will guard against the Theatrical form, to which many of our new churches, and chappels too nearly approach.’

Yet in one sense of ‘theatrical form’ (not perhaps Hickes’s), what Wren called ‘the auditory kind of church’ needs just that. It requires a single space, a good view of the actors and a clear acoustic – Wren went so far as to define the limit of church size in terms of how far a man’s voice would carry. While the preacher will speak from one side – centre stage is reserved for the communion table and its attendant mysteries – a pulpit high enough to give preacher and congregation a good view of one another is important. A lectern or reading desk and pews are the only other necessary furniture.

A generic medieval parish church would have, as well as a nave and altar, aisles, a chancel and, perhaps, chapels. These had fallen into disuse, and although they would become functional again in the 19th century, when Anglicans began to revive the forms of Catholic worship, they were not in the specification for the new churches. Architectural and liturgical fashion are not always in step, but the rectangular preaching box the Commissioners wanted served the taste and ambitions of English baroque architects pretty well. While it excluded the multiple symmetries possible with a Greek-cross or an oval plan (Hawksmoor first proposed an oval plan for St George’s), it had none of the bits-added-on character of the older model. It offered a simple volume in which to play games with the classical orders. They, and the rules associated with them, both stimulated invention and put a limit on personal eccentricity.

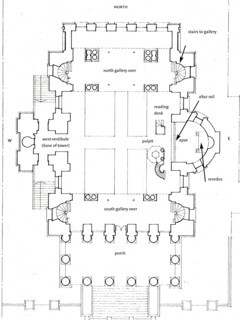

Although the Commissioners’ specifications set some bounds on architectural imagination, they were not tight – the stylistic variety of the designs accepted proves it. Any idea that all the new churches should be built to a single design was dropped early on. What presented problems at St George’s was the conjunction of the Commissioners’ insistence on an eastern orientation and the nature of the site they had acquired from Lady Russell (the Bedford family owned much of Bloomsbury). It was quite small, already surrounded by houses, and longer from north to south than from east to west. James Gibbs, one of the surveyors appointed by the Commissioners (Hawksmoor was the other), submitted one plan, Vanbrugh another. The latter was on a north-south axis because, he said, the church could not ‘be conveniently built any other way’. Hawksmoor rose to the challenge and proved that it could be, although whether ‘conveniently’ is arguable. The problem was how to put an east-west church onto a north-south site and still provide the seating required. The plan Hawksmoor came up with is shown above.

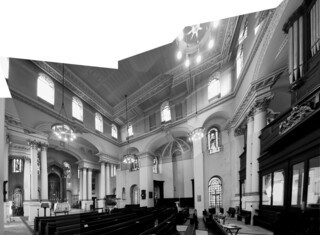

To the right are some photographs I patched together a while ago which give a sense of what it was like to stand in the south-west corner of the church. The central space is a cube – as wide as it is high as it is long. The primary focus, as Hawksmoor planned it, was the apse, seen in the centre of the picture, which extends the central square outwards to the east. Within the apse stood an elaborate pedimented wooden reredos. It was moved to the north side of the church in 1781 and can be seen through the double arch on the left of the picture. The vestibule at the base of the tower – behind and to the left of the place from which the picture was taken – marked the west end of the axis. Galleries outside the north and south sides of the cube were divided from it by double columns which supported both the galleries and wide segmental arches above them. There is still a south gallery; it houses the organ and can be seen on the right of the picture (the glazed screen below is recent). In the original set-up the north gallery was occupied by the Montagu family and their liveried retainers, the other, facing it, by the Russells and theirs. They may have been furnished like stage boxes with chairs rather than pews. Because the galleries were not within the central square, and partly masked the extensions to north and south, they increased the visual importance of the east and west walls. Rows of pews probably faced each other, choir-style.

Fashionable London lay to the north: Montagu House was on Great Russell Street – it would later become the British Museum – and as the century progressed, well-off families moved into the new Bloomsbury streets and squares. So the more distinguished class of parishioner entered the church from the west end by way of steps which led up to a vestibule under the tower. It was the prosperous members who had petitioned for a new church in the first place. They wanted to avoid having to go through the Rookery – rough streets like the ones shown in Gin Lane – as they had to on their way to St Giles in the Fields. If your route to St George’s was from that poor, south side of town you could enter by way of the great porch. You were then drawn forward by the light which streamed down from the clerestory windows set in the top – the attic storey, as it were – of the cube. A turn to the right brought you face to face with the altar. It is hard to think of the huge portico as the equivalent of the south porch in a country church, but functionally that is what it was. It implied something which was contradicted as soon as you got inside. What looked like the main axis turned out to be the minor one: the orientation the grand frontispiece implied was not the true one.

This layout was unstable, and the orientation quite quickly flipped. In 1731, the year after the church was consecrated, there was a premonitory twitch when a west gallery was added. In 1781, the altar and reredos were moved into the north extension, the north gallery was removed, and an east gallery was built. The liturgical east end was now the geographical north end. The north-south orientation the portico implies had won; eventually, the west entrance would be closed off altogether – it will be restored as part of the current works. Street’s removal of the east and west galleries in the 1870-71 works brought further confusion – they were elements which had given an altar-wards direction to the central square. As on an amphisbaenic ferry you now have to ask yourself which way the vessel is pointing. The stained glass inserted during Street’s watch destroys the natural play of light – the Commissioners had specified well-lit churches. The windows are, I am told, good of their kind, or at least interesting, and certainly a significant part of the post-Hawksmoor history of the church – which means that they will not be removed without objections. What Street was trying to do – make a church sympathetic to services in which a revived Anglo-Catholic liturgy was used – involved setting the north extension out as a chancel and making the interior dimmer and richer. This sat uneasily with the classical structure Hawksmoor had designed.

In 1930, there was an appeal to raise £2000 as a ‘bicentenary thanks offering’. A series of lectures was given by, among others, T.S. Eliot, J.C. Squire, Laurence Binyon, Helen Waddell and Harold Monro. The money was spent on black and white marble, to replace Street’s ‘ugly tiles’ and ‘18th-century chairs of good design’ to replace his pews in the chancel. The new plan is to remove the marble flooring, put the reredos back in the apse and perhaps restore the easterly orientation. It is even possible that the north gallery will be reinstated. If it isn’t, the directional ambiguities Hawksmoor had more or less tamed may still be troubling. Or maybe that is the wrong way to see it. Kerr thinks that ambiguity is at the heart of the design: ‘Hawksmoor,’ he says, ‘achieved a balance which is dynamic. The building demands engagement – it cannot be easily assimilated. The proposals – without a north gallery – strive to set up the dynamic again, albeit without being literal.’ Some changes are by their nature ephemeral. When you learn that the interior was originally painted stone colour, the gilded capitals and blue ceiling of the last redecoration seem out of place, but no deep problems arise. Who is going to complain about fresh paint?

Like all classical architecture, Hawksmoor’s is rhetorical. Its inventiveness and individuality have to do with the way grammatical elements are strung together and rules are used, broken or elaborated. Like all notable architects he has a tone of voice. The work of the best architects in 18th-century Britain have something of the light, controlled brilliance of Pope’s heroic couplets. Hawksmoor’s tone is, by contrast, heavy and Miltonic. Models would probably tell most about him. St George’s is a puzzle you take apart and put together in your mind: to be able to pick it up, take the roof off, turn the pieces about and reassemble them would reveal its geometrical complexity. The Commissioners clearly used models to judge churches. By 1714, there were at least 13 of them in their office; the one for St Mary le Strand still exists.

Did Hawksmoor’s work attract particularly punitive improvers? Maybe. But one must remember that the parishioners did not choose their architect, and even great architects – particularly great architects, perhaps – can design churches which meet their own needs but not the congregation’s. There is architectural space and liturgical space; a project which aims at saving a masterpiece of the first kind must also take account of the needs of the second.

St George’s is not just a monument of early 18th-century architecture, it is also a working church. From this month it will be closed, but will open again, it is hoped, before Christmas 2004. At the moment the church is like a sheeted patient waiting for an operation. Scaffolding and plastic cover it inside and out. A plastic-sheeted passage leads up the steps and through the porch into the part-wrapped nave.

If the parishioners of 1730 came to St George’s today, much of the service would be familiar, but the coloured vestments and the larger number of active participants – a priest, an assistant, two or three servers – taking part in the Eucharist would reveal to them the effect of the moves which, from the middle of the 19th century, took some Anglicans back towards their Catholic past. The visitor from 1730 would find the church strangely empty. It was planned for congregations of around four hundred, at one point as many as nine hundred were crammed in. But during the 20th century numbers dwindled, as a result of a general falling off in church attendance and changes in land use – in particular, the expansion of London University into houses in the Bloomsbury squares. The resident population of the parish is now 1500, a typical congregation twenty or thirty – perhaps double the number of a few years ago.

Congregations were already small when Father Roberts (1873-1953), the most remarkable of recent incumbents, was rector. He was a socialist, a pacifist and a feminist – in favour not only of women’s suffrage but also of their ordination. Under the name Susan Miles, his wife, Ursula, wrote a novel in verse, Lettice Delmer, now republished by Persephone Books. In an earlier poem she wrote:

I do not want to visit the churchwarden’s wife

She will use her saw-like voice on me and will deplore the fact

That I ‘don’t visit’

She will tell me that I should make ‘quite a

nice little parson’s wife’,

If only I would give up all that silly nonsense about the Vote

And turn my thoughts to duties

That lie nearer home.

Susan Miles also wrote a biography of her husband which is more than a touch cloying, but it does give a sense of how imperfectly the architectural grandeur of St George’s matched the life of a parish and congregation much reduced in numbers and resources. It was a long time since it had been a fashionable church with ‘687 sittings for which substantial rents were paid’. Most of the problems which exercised Roberts were straight from Gin Lane. He was particularly distressed when the Church Council decided that the down-and-outs had to be ejected from the portico, where they resembled the tattered figures that Piranesi dots around his engravings of Roman ruins.

A wary atheist, I enter churches as an intruder who does not wish to be intrusive. I obey requests for seemly behaviour and slip quietly past those who kneel or are gathered for services. If there is music I may sit at the back and listen, but I cannot join any act of worship. I buy postcards, pick up the brief history and put my money in the box, but I will not turn pleasure in the way things look and sound into belief. Yet I know my pleasures are parasitic on belief, or at the very least on other people’s willingness to carry out the actions of a believer; these are the necessary cause of church building, and of the continuing use which keeps them alive.

Hawksmoor’s fame and the magnificence of his building attract funds. A donation of $5 million from the estate of Paul Mellon, which came with the stipulation that it must be spent by October next year, got the restoration started. The church’s needs were given a higher profile when it was put on the World Monuments Fund’s watch list of the 100 most endangered sites. Another £2.3 million will come from the Heritage Lottery Fund, once the rather complicated stipulations attached to the grant have been met. A charity called Robert Wilson Challenge matches funds raised locally. The finances for the restoration are pretty nearly in place.

What is St George’s future as a parish church? Its congregation has been growing, and the efforts of some regular parishioners drove forward the project to restore the building. There are plans for the undercroft, which seems from the beginning to have served as a school, and educational uses are possible. There is talk of a permanent Hawksmoor exhibition.

The difference between a church building like St George’s which seems to have been planned as a tribute to the grandeur of God and one kept modest so that the Word may be heard in a plain space – the difference between Hickes and Vanbrugh, if you like – is an easy one to read. Being an atheist of the puritanical persuasion I have a penchant for the second kind – the Dutch did them very well. Some of the plans for St George’s – less gilt and blue paint, for example – will take it in that direction. But just as important for the intrusive non-participant is the fact that other people will be participating.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.