Hide your wives and daughters

Hide the groceries too

Great Nations of Europe coming through . . .

They came in good ships; their guns were the best. First were the Portuguese, then the Dutch. The English followed. The destinations were India, Sumatra, Java, Japan, China and the Spice Islands. It had taken the crews the best part of a year of foul food and slow sailing to get there. Many had died on the way. When they arrived, the different nationalities pushed, squabbled, tricked, fought and cheated each other – not to mention the natives. Illness took men in such numbers that luck had a great say in who was successful. For more than three hundred years, from around 1600 until the European empires finally fizzled out, the Great Nations of Europe gave the world an early taste of the pleasures and perils of globalisation.

They wanted to trade: the market at home was eager (at one time or another) for spices – pepper, nutmeg, mace and cloves. They wanted textiles: silk from China and ‘fine muslin, printed chintz and palampores, plain white baftas, diapers and dungarees, striped allejaes, mixed cotton and silk ginghams and embroidered quilts’ from India (‘a definitive glossary of types has yet to be made’). From China they wanted porcelain and tea. Almost any product of the Asian world from indigo and coffee to diamonds, fans and lacquer was saleable. But what had the Europeans to offer in return? Silver, of course – from the American mines. English broadcloth; spectacles and telescopes; mirrors, knives and sword blades; and unwrought metal – lead, iron and tin. It wasn’t enough; there was clearly a balance of payments problem. There were a few subtle and several brutal solutions.

Anthony Farrington’s book, which accompanies and supplies many of the captions for Trading Places: The East India Company and Asia 1600-1834, a British Library exhibition that runs until 22 September, pulls you up as you look around. You may feel that you have stepped into the best provincial antique shop ever: Farrington reminds you that what you are looking at is material evidence of a punishing cultural encounter, driven by a desire for the smell, taste, colour and texture of exotic stuffs and essences.

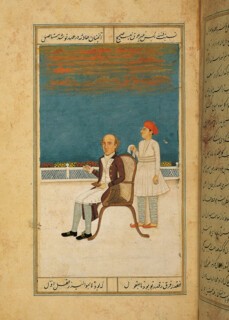

The exhibits are entrancing. There are prodigies of topographic and botanical record-making by native artists, produced to the order of foreign patrons – for example, the splendid panoramas of Delhi in 1846 and Canton c.1760. There are painted, printed and embroidered textiles and Chinese dinner plates emblazoned with European arms. Almost every image and object makes you aware, in one way or another, of the foreignness and often the grossness of our European ancestors. In the panorama of the Canton waterfront, the classical columns that support arcades and loggias make a barbaric contrast with the surrounding maze of Chinese buildings. Captain William Knox is shown receiving from a scribe the manuscript he has commissioned of the Lalitavistara or Sutra of Great Magnificence; the conventions of the miniaturist make him blend nicely into the background, but it is tempting to believe that the pattern of checks and gold spots on his breeches was the result of scribal horror at an undecorated surface. The contrast in this Mughal miniature between Warren Hastings and his servant c.1782 – it is hard not to read a hint of a joke in the oddly large proportion of Hastings’s head to his body – reminds me of what a guide, at the end of a cultural tour of China, said to a friend who pressed her about what she really thought of the Westerners she had been shepherding: ‘Well,’ she said, giggling, ‘we wonder how you can be so happy when you are so ugly.’

Both China and Japan acted vigorously to keep the traders at bay. The Chinese made them hand in their guns at the door; canon and gunpowder were unloaded and sequestered between the arrival and departure of the trading ships. Both countries limited traders to specific areas and settlements. The Chinese would not let them stay over from one trading season to the next.

The East India Company had a trading monopoly. It was regulated by a charter which insisted that a proportion of what was purchased in the East should be paid for by British exports; the 1693 renewal ordered the Company to export £150,000 worth of manufactured goods as well as bullion and coin; that of 1698 stipulated that 10 per cent of its annual exports should consist of English products. Broadcloth was not in much demand in the tropics, although there was a limited Japanese market for linings for weapon and armour boxes and for horse-cloths and as furnishing fabric. The Company had to discover ways of balancing the cost of imports. It was found, early on, that trading in the East was the best way to get round that problem – behaving, in other words, like a modern multinational. One scheme was to buy silk in South-East Asian ports, sell it in Japan for silver from the new mines there, use part of the proceeds to buy pepper and spices at Bantam, and thus return to London with some part of the profit of the voyage in hard currency. The plan ‘was all nonsense’, Farrington says, ‘not least because silk was hardly ever available to the English in sufficient volume’.

More comical were cultural misunderstandings and miscalculations. ‘Fantastically painted or striped’ Indian textiles sold well in Japan one year. The next year only white spots on dark blue or black backgrounds were wanted. A couple of ‘gallipots’ – pieces of crude earthenware – from England somehow found their way to Japan and were picked out at one point by some ‘warrior connoisseur’, as Farrington puts it, because they resembled ‘sophisticatedly naive’ tea-ceremony pottery. News went back to London that cheap pots fetched fabulous prices. When the Japanese factory (‘factory’ as in ‘factor’s establishment’) closed some years later, the shipment of 2161 assorted gallipots was still in the warehouse. The Japanese factory did not last – following the whims of local fashion would have strained the instincts of a modern department-store buyer.

The largest personal fortunes were made in India when the Company became the de facto government. A cut of the tax revenue was much more profitable than the hard graft of trade. Once you could administer a monopoly – corner the opium market or tax salt – the balance of payments problem disappeared. Newspaper illustrations from 1882 of the huge Patna opium factory warehouse, showing high racks stacked with balls of the drug, give some idea of the scale of the trade. ‘Free trade in East Asia,’ Farrington says, ‘came to mean the lucrative and immoral freedom to deliver drug cargoes to Chinese addicts.’

Company men returning with immense fortunes – ‘nabobs’ – became stock figures of fun: rich, vulgar and pushy. But the world they had left was truly fabulous. Put William Daniell’s bleakly elegant aquatint of the East India Docks in 1808 (the view is south to the Greenwich marshes) beside a Mughal miniature of sightseers visiting the Taj Mahal made about fifty years earlier. The comparison makes European life seem literally, and sadly, monochrome.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.