It adds greatly to the glamour of this book that its author was threatened for having written it. Her offence was to argue that many of the passing media events of our culture – chronic fatigue syndrome, Gulf War syndrome, satanic ritual abuse allegations, alien abduction fantasies – are forms of mass hysteria. This so enraged American sufferers of chronic fatigue syndrome that they threatened to kill her. The fact that people so tired they can barely get out of bed could muster the strength to do this would be comic if it weren’t so alarming.

What they are resisting, with such vehemence, is Showalter’s claim that they are just depressed. By calling their condition a syndrome, sufferers want to give it the dignity of a strictly medical and physical origin. They also want to escape the responsibility for their state which would be unavoidable if it were shown to be ‘all in the mind’. Showalter’s claim is that to do this is to fabulate a ‘hystory’ – to use her ungainly neologism. A ‘hystory’ is a story consciously or unconsciously designed to make unhappy lives interesting. Being depressed, after all, has little conceptual interest. It is not something you want to talk about, not something you want to ‘share’. But if you have a syndrome, you have an audience, and if its causes are unknown, you have a mission – to find out what they are – which can enlist the sympathy and attention of medical practitioners. A syndrome offers those who may be having a hard time the validation of the victim’s role. Validation seems to be the key here – and it is Showalter’s attack on their system of inner validation which makes chronic fatigue syndrome sufferers so angry with her.

If chronic fatigue syndrome is a form of depression, the puzzle is why it’s so difficult to admit to being depressed. We live in the most heavily psychologised culture in the history of mankind. We are awash with psychobabble. Why then do some people so stubbornly resist the idea that their physical symptoms might have ‘merely’ psychological causes? Some very strong de-validation of their experience is being offered by our ambient psychological culture, and rather than accept this, unhappy people are – according to Showalter – writing their own hystories.

Gulf War syndrome is another example, Showalter argues, of a hysterical refusal to accept that symptoms are psychosomatic. As many as 60,000 American veterans returned from the Gulf complaining of a variety of problems, ranging from headaches to nausea. For years they have insisted that a mysterious agent – Iraqi nerve gas or the insecticide sprayed on the inside of their tents – might be responsible. As their distress continues, the veterans’ symptoms have spread to their families and taken on a certain baroque extravagance: for example, wives have reported that, since returning from the Gulf, their husband’s semen burns them during intercourse.

The fact that we take many of these complaints seriously is a sign of how far we have become a Freudian culture. In 1914, patients wouldn’t have ventured forth to a doctor with such symptoms, and if they had, the doctor would have briskly sent them home again. In the Nineties, sympathetic politicians from President Clinton down have promised action on Gulf War syndrome; a US Government Commission, costing $80 million, was appointed to investigate and scientists did their best to track the common cause of symptoms so various that they could scarcely be regarded as belonging to a single syndrome at all. The fact that scientists failed to find any convincing explanation has only redoubled the paranoia of the sufferers, who are convinced that the Government is covering up some military malfeasance in the desert.

The most likely explanation, Showalter argues, is that many of these veterans are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and would benefit from counselling and therapy. Rather than accept this, veterans are seeking a physical cause, and in so doing, according to Showalter, are merely deferring their reckoning with inner conflicts about war and its aftermath. It’s possible, though Showalter doesn’t make this point, that the Gulf War had special features which rendered its veterans especially susceptible to post-traumatic stress. The most important of these is that the folks back home couldn’t believe that it was stressful at all. Those who came home after a war which, in the public’s mind, lasted a hundred hours and resulted in total victory, had unusual difficulty in finding people willing to credit experiences of loneliness, fear, exhaustion, terror and guilt, which the Gulf conflict, like any war, offered in abundance. Veterans found they awakened more sympathy with the claim that their symptoms had identifiable physical causes, like faulty insect repellent.

Showalter has angered the veterans, just as she has angered all the others, with her claim that they present a picture of clinical hysteria. Since the word ‘hysteria’ has been bastardised as it has been popularised and now serves as little more than an abusive term for female irrationality, sufferers of chronic fatigue or Gulf War syndrome don’t take kindly to the description. The deeper difficulty with Showalter’s diagnosis of hysteria is that it is unclear to which precise set of medical conditions the word refers. The condition that Freud and Breuer encountered in their late 19th-century consulting-rooms has vanished. As Showalter points out in a useful history of the idea, the accepted line is that by the not so swinging Sixties, the well of Victorian repression had dried up and with it the supply of those superbly expressive hysterics – such as Dora and Anna O. – who took starring roles in Freud’s casebook. What then is left of hysteria as a definable syndrome? Showalter admits that the line between hysterical symptoms and psychosomatic ones is unclear, but her own penchant for diagnosis at a distance seems to muddy the distinction still further. She is right to denounce the diagnostic legerdemain of the various quacks and charlatans who seize on the distress of gullible people, but she does a fair bit of diagnosing herself, and since she does so without meeting the people in question, they have some reason to be annoyed with her exercises in labelling.

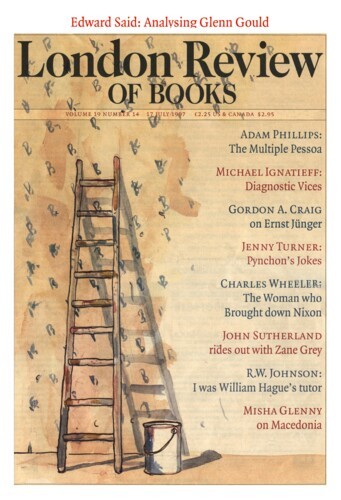

Hystories is a study of hysterical discourse – a literary critic’s descent into the netherworld of books on satanic abuse, recovered memory syndrome and so on. It is not actually a study of the people who are afflicted with these – what is one to call them? – miseries. But Showalter keeps pronouncing on the probable causes of their distress, as if such diagnosis at a distance is unproblematic, as if their hysterical discourses can be translated straightforwardly into the diagnostic manuals of late modern psychiatry. I don’t doubt that some of these people are barking mad, if only in connection with a single subject, but Showalter’s case against their credulity would be stronger if she didn’t keep succumbing to the diagnostic vices she denounces in others.

For example, she examines the case of a Jewish biochemist in her forties whose history is related in a book about multiple personality disorder and ritual satanic abuse. After detailing this woman’s allegations that she was raped by her father, tortured during anti-semitic rituals and forced to witness the murder of a baby, Showalter maintains that these ‘recovered memories’ were a hystory, revealing the woman’s ‘own sexual guilt and the puritanical values of her community, especially in relation to women’. ‘Nice Jewish girls,’ Showalter continues, ‘are not supposed to be sexually titillated by the Holocaust.’ It seems shallow and breezy to attribute the ‘recovered memories’ of a person you have never met to the guilt supposedly associated with being a ‘nice Jewish girl’. By calling these delusions a form of hysteria she is falling into the phoney psychologising she denounces in others.

Showalter traces much of this to the nefarious psychic hold of American fundamentalism and sexual puritanism. But to make religious and sexual repression explain everything is to practise a tenacious form of secular liberal condescension – East Coast sophisticates having their revenge on those poor benighted Southern and Midwestern souls who went to church, believed in family values and ended up also believing in the Devil and all his works.

Instead of calling such phenomena outbreaks of hysteria, why can’t we think of them as outbursts of credulity? Instead of psychologising their causes, why don’t we think of them as examples of gullibility and charlatanism, showing the dubious effects of a culture which has generalised psychobabble without providing the structures of intellectual authority to regulate its clinical and legal excesses? Showalter doesn’t touch on the question of intellectual authority but it is centrally important. What is one to make, for example, of the medical school at the University of Utah, which gives houseroom to a professor who teaches students that ‘satanic cults are part of a Nazi conspiracy led by a renegade Jew.’ Lest one suppose that the problem is confined to backwoods institutions, consider Harvard Medical School, which allowed Professor Judith Lewis Herman to purvey extravagantly exaggerated theories of ‘recovered memory’ syndrome. The same institution harbours Professor John Mack, who believes that beings from outer space are abducting men and women and conducting fertility experiments on them. As Showalter observes, ‘to Mack, looking for material evidence is a logical error, typical of the material bias of Western scientists, who operate at a lower level of consciousness than the aliens.’ Quack epistemology of this sort does appear to have aroused some disquiet among his colleagues, but when a faculty committee issued a report critical of his research, Mack’s lawyers – this is America – claimed that his right to academic freedom was being challenged. In August 1995 Harvard backed off.

The problem of intellectual authority is much bigger than the timidity of universities, however. The enthusiasm for the Internet, for the supposedly democratic character of the unsorted torrent of information, mixed with untreated intellectual sewage which spews forth into our computers, leads one to suspect that re-asserting intellectual authority in our culture will not be easy. One of the illusions of the 20th century was that science and democracy would march hand in hand, diffusing knowledge and enlightenment from the élites to the masses. Some of this has come to pass, but there has also been an unpleasant counter-current, in which populism has been turned against legitimate scientific expertise. The result has been an explosion of democratically validated credulity. The cult of celebrity makes everything worse: the charlatans who do most harm have chat-shows and fill the shelves of Barnes and Noble with diets, regimens and psychobabble which cater to the public’s cravings for redemption. These mountebanks cultivate an image of democratic insurgency against the certifying authorities of the medical professions.

But facts, as they say, are stubborn things, and in the end those who possess some reasonable grasp of them are likely to prevail over those who purvey fantasy and half-truth. But because democracy institutionalises the suspicion of experts, it may well take a very long time for genuine expertise to win out. And the media, by and large, much prefer a bug-eyed charlatan to a sober number-cruncher. Thanks to the media, the virus of credulity now enters the bloodstreams of entire cultures. The X-Files makes television entertainment out of the clotted confusion of credulity and paranoia which sometimes seems to pass for public culture in the United States.

Showalter never quite addresses why there is more of this foolishness in America than in, say, Britain. Of course such comparisons are an unmissable occasion for displays of chauvinism and cultural condescension, but it is hard not to see something specifically American about this phenomenon. Showalter, a frequent and admiring visitor to Britain, concurs, but doesn’t get close to an explanation. British culture is supposed to be more cautious and empirical; it may merely be more deferential. The intellectual authority of the BBC, university experts, the Government’s scientific advisers and media commentators is less contested, less buffeted by populist paranoia, than in America. Why this is so is not easy to explain. After the Kennedy assassination and the failure of the Warren Commission to provide a satisfactory account of it, Americans in ever larger numbers began to distrust the veracity of government information. By the Eighties, this paranoid cynicism, worked on by a media ever assiduous in pandering to public opinion, began to bring forth truly fantastic offspring, such as alien abduction theory.

The irony, of course, is that when some mad episode of credulity is at its peak, everyone turns to scientists to restore clarity if not sanity. Anxious governments commission panels of scientists to determine whether flying saucers did or did not land in East Texas in 1947; whether little Johnny was or was not subjected to satanic abuse; whether Sergeant Jones’s respiratory infection does or does not have to do with the stuffing in his army-issue sleeping-bag. In the end, only the scientists can answer the poisonous questions which credulity, charlatanism or unadulterated bafflement drop into the reservoirs of public culture.

Showalter is on the side of the Enlightenment, on the side of reason, argument and even a good laugh. She is to be thanked for taking us on this tour of the nether regions of American delusion, but she keeps making these phenomena larger and more menacing than they really are: she speaks of epidemics, when we’re really talking about outbreaks. She inflates the subject by making vague connections between these outbreaks and the millennial anxieties of the age. She psychologises the phenomenon, when we should be subjecting it to as much sharp-humoured irony as we can muster. The portentous tone continues to the very last words of the book, where she writes: ‘if we can begin to understand, accept, pity and forgive ourselves for the psychological dynamics of hysteria, perhaps we can begin to work together to break the crucible and avert the coming hysterical plague.’ Hysteria is catching, and Showalter may have caught it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.