The dilemma: it is 1892, you are a 30-year-old female shop assistant in a small silk manufacturing concern in Geneva, the city of your birth. You live with your parents in a modest but pleasant suburban house; you travel to work on the streetcar. You have no suitors, but don’t really mind: you have a spiritual protector named ‘Léopold’, a reincarnation of the 18th-century magician Cagliostro, who appears to you in visions in the long brown robe of a monk, offering advice and emotional solace. Your main hobbies are embroidery – of mystic shapes and patterns bearing no resemblance to anything in the visible world – and the obsessive cultivation of states of ‘obnubilation’, during which ‘strange multicoloured landscapes, stone lions with mutilated heads, and fanciful objects on pedestals’ float before your eyes.

Yet life is tedious beyond words. Your parents’ provincial ways annoy you (you’re not convinced they really are your parents); the grey Genevan skies oppress. You hate being a ‘little daughter of Lake Léman’; you feel yourself born for a higher sphere. Above all, you have an overweening desire to enthral: to exhibit ‘the magnificent flowering of that subliminal vegetation’ – your inner life – before a throng of enraptured admirers. But how to get the attention you deserve?

If you are ‘Hélène Smith’ – the shop-girl in question and subject of the Swiss psychiatrist Théodore Flournoy’s sensational 1899 case-history From India to the Planet Mars – you solve the problem in classic 19th-century female-monomaniac fashion: by becoming a spirit medium. Initiated into table-rapping in the winter of 1891-2, Smith – whose real name was Elise Müller – progressed quickly from bouts of automatic writing and glossolalia to extended trance-states in which she revealed that she had lived a number of glamorous past lives: as ‘Simandini’, a beautiful Hindu princess forced to commit suttee in the early 15th century; as Marie Antoinette, doomed Queen of France; and perhaps most intriguingly, as a visitor to Mars, whose inhabitants, language and customs she was able to describe in phantasmagoric detail. At weekly séances over the next few years Smith produced an array of ‘proofs’ of these past existences and simultaneously enlisted a doting crowd of followers convinced of her psychic powers.

It was Smith’s triumph – and her subsequent misfortune – to attract the attention of Théodore Flournoy (1854-1920), professor of psycho-physiology at the University of Geneva, friend of William James (and later Carl Jung) and enthusiastic debunker of putatively occult phenomena. Since the late 1880s Flournoy, whose deceptively chivalrous, self-effacing manner concealed a penetrating forensic intelligence, had eagerly sought a medium on whom to test his evolving theories about the relationship between trance phenomena and the psychopathology of the unconscious. Introduced to Smith in 1895, he at once struck up a friendship with her and asked if he could study her in action. Exalted by his interest and avid to convert him to the ‘beautiful doctrine of spiritism’, Smith not only welcomed him at sittings for the next four years, but permitted him to subject her to various uncomfortable physical experiments, including pressing on her eyeballs and sticking her with pins during trance-states to test for localised anaesthesia and absent or impaired reflexes.

Flournoy’s professional curiosity at once inspired the excitable seeress to new mystic heights. Smith was what Flournoy would dub in From India to the Planet Mars a ‘polymorphous, or multiform, medium’ – that is, a medium subject to a diverse, highly theatrical range of automatisms while in the trance-state. Not only was she able to receive messages ‘through the table’ from beings such as her spirit guide Léopold, who frequently manifested himself during sittings as a kind of disembodied play-by-play commentator on what was going on: she could gabble in mysterious tongues, write and draw in hands other than her own, and drastically alter her voice and physiognomy as she gave herself up to various spirit ‘controls’. By far the most impressive demonstrations of her mediumship, however, were what Flournoy called her ‘somnambulistic romances’ – the grandiose, quasi-mythopoetic fantasies of having lived at other times, in other worlds.

It is hard to say which of her ‘romances’ was most bizarre: each was a marvel of intricate, exfoliating absurdity. A set of ‘Martian’ visions witnessed by Flournoy in 1896, for example, began with the entranced medium speaking to ‘an imaginary woman who wished her to enter a curious little car without wheels or horses’. After pantomiming the act of climbing into a car Smith performed a series of contortionist gestures indicative of extraterrestrial travel:

Hélène ... mimics the voyage to Mars in three phases, the meaning of which is indicated by Léopold: a regular rocking motion of the upper part of the body (passing through the terrestrial atmosphere), absolute immobility and rigidity (interplanetary space), again oscillations of the shoulders and bust (atmosphere of Mars). Arrived upon Mars, she descends from the car, and performs a complicated pantomime expressing the manners of Martian politeness: uncouth gestures with the hands and fingers, slapping of the hands, taps of the fingers upon the nose, the lips, the chin etc, twisted courtesies, glidings and rotation on the floor etc. It seems that is the way people approach and salute each other up there.

Such rituals completed, Smith would then exclaim over the odd sights before her – Martian men and women in ‘hats like plates’, peach-coloured earth, trees that widened as they ascended, pink and blue canals filled with ‘horrid aquatic beasts like big snails’ and so on – and hobnob with various Martian personages. Chief among these was a wizard-like being named Astané who was inevitably accompanied by a creature with the head of a cabbage, a big green eye in the middle and ‘five or six pairs of paws, or ears all about’. Sometimes Astané took hold of Smith’s index finger and made her write Martian words, such as dodé né ci haudan té mes métiche Astané ké dé mé véche, later translated through the table as: ‘This is the house of the great man Astané, whom thou hast seen.’ On awakening, Smith – who claimed not to remember what she said or did while entranced – would examine with amazement the errant bits of ‘Martian’ thus produced.

The ‘Hindoo’ and ‘Royal’ fantasies were equally colourful. Under the sway of her Hindoo vision Smith re-enacted episodes from her life as the unfortunate Simandini: her betrothal to the handsome Prince Sivrouka; their courtship in the splendid palace gardens at Tchandraguiri; the happiness of married life, complete with cavorting handmaidens and pet monkey; her anguish at her husband’s premature death; her frightful despair as she mounted the funeral pyre on which she was bound to perish. Flournoy himself was often roped into these tragicomic tableaux: after the table revealed that he was himself the reincarnation of Sivrouka, Smith quickly incorporated him into the fantasy mise en scène as ‘her lord and master in the flesh’, showering him with caresses and ‘affectionate effusions’ in a weird pseudo-Sanskrit.

Reliving scenes from her life as Marie Antoinette, Smith would flutter an imaginary fan, mimic taking snuff and throwing back a train, and address Flournoy and his fellow sitters as if speaking to members of her court. A sitter named M. Demole was recognised as the current reincarnation of Philippe d’Orléans; another as that of Mirabeau. Each then had to improvise witty repartee while Smith-as-Antoinette discoursed on 18th-century fashion and politics. Her demeanour during these confabs was appropriately regal – her innate taste for everything that is ‘noble, distinguished, elevated above the common herd’, Flournoy wrote, lending each gesture a perfect ‘ease and naturalness’.

Granted, there were occasional cock-ups. ‘Her Majesty’ sometimes fell into the verbal booby-traps her interlocutors set for her – as when words such as bicycle, tramway or photography were introduced into supposedly 18th-century conversations. Not recognising the anachronism at first, ‘Marie Antoinette ... allows the treacherous word to pass unnoticed, and it is evident that she perfectly understood it, but her own reflection, or the smile of the sitters, awakens in her the feeling of incompatibility; she returns to the word just used, and pretends a sudden ignorance and astonishment in regard to it’. In one unfortunate instance she calmly smoked a cigarette – proffered by a sly Mirabeau – before realising with a grimace that she did not understand ‘the use of tobacco in that form’.

But little seemed to faze the medium in the grip of such fancies – not even the grotesque irruption of yet another retroactive personality. It was one of Smith’s pet notions that her spirit control Léopold, in his earlier incarnation as the magician Cagliostro, had been Marie Antoinette’s lover in the years before the French Revolution. Thus even as she performed her royal part, she might suddenly be ‘taken over’ by Léopold, who assuming his former identity would expatiate on his passion for the tragic queen. ‘Her eyes droop,’ Flournoy wrote; ‘her expression changes; her throat swells into a sort of double chin, which gives her a likeness of some sort to the well-known figure of Cagliostro.’ After a series of hiccoughs and sighs indicating ‘the difficulty Léopold is experiencing in taking hold of the vocal apparatus’, the ‘deep bass voice of a man’ would issue from her throat ‘with a pronunciation and accent markedly foreign, certainly more Italian man anything else’.

When Flournoy – who candidly admitted the surreal fascination Smith’s performances held for him – began writing up From India to the Planet Mars in 1898, the besotted medium seems to have assumed, with more vainglory than sense, that he would champion her supernatural lucubrations. Certainly she responded helpfully to his scores of seemingly innocent questions about her early life, peripheral daydreams, reading, knowledge of foreign languages and the like. But any satisfaction at being the object of such scrutiny vanished once the book itself appeared. For Flournoy had launched a devastating assault on her claims. Her tales of past lives were simply unconscious projections, he wrote, ‘subliminal poems’, akin to ‘those “continued stories” of which so many of our race tell themselves in their moments of far niente, or at times when their routine occupations offer only slight obstacles to daydreaming, and of which they themselves are generally the heroes’. Down to the most freakish detail, every element contained in them, he proposed, could be explained by purely psychological mechanisms.

Crucial to Flournoy’s explication was the phenomenon of cryptomnesia: the process by which forgotten perceptions, relegated to the unconscious, undergo ‘subliminal elaboration’ and return to awareness in an estranged yet vivid form. What Smith claimed to experience as memories of past lives, he suggested, were in fact bits and pieces out of her own psychic past – remnants of earlier perceptions, now disguised and incorporated into extended narcissistic fantasies.

For every feature of Smith’s ‘romances’ Flournoy set out some unexceptional, even banal, unconscious aetiology. Her descriptions of Martian flora and fauna derived, he thought, from a ‘buried’ acquaintance with Camille Flammarion’s bestselling book La Planète Mars et ses conditions d’habitabilité (1892), a volume of fanciful speculations about life on Mars popular in spiritualist circles. The name Simandini – which came through the table first as ‘Simadini’ – was a ‘hypnoid distortion’, he proposed, of Semadeni, the name of a long-established family of Genevan dry-goods merchants. Smith’s descriptions of Sivrouka and his palace followed almost verbatim passages from ‘De Marlés’s history of India’ – a book conveniently located on the shelves of the Geneva Public Library. The romantic fantasy about Cagliostro and Marie Antoinette was ‘probably inspired’ by an engraved illustration from a Dumas novel about the French Revolution hanging in the home of one of Smith’s friends – and so on.

Most damningly, with the help of Saussure, his colleague at the University of Geneva who was not only a linguist but a Sanskritologist, Flournoy demonstrated that the glossolalic scraps of Martian and pseudo-Sanskrit Smith disgorged while entranced – the feature of her mediumship most baffling and impressive to lay observers – were nothing more than ‘infantile’ imitations of French. However exotic-seeming individual words, the grammar and syntax were ‘puerile counterfeits’ of Smith’s mother tongue. Like her other fabrications, these uncanny mock-languages were ‘subliminal creations’ – the fantastic by-product of a personality profoundly, exorbitantly, at odds with the real.

Smith’s reaction to all of this was predictably explosive: Flournoy had cheated and traduced her. When From India to the Planet Mars became both a popular and a critical success – it went through numerous editions and was hailed by Mind as a classic of psychological inquiry – the outraged medium demanded (and received) half of Flournoy’s royalties. But neither the psychologist’s money, nor that of an adoring American benefactress whose assistance allowed her to devote herself to séances full-time, seemed to salve her wounded spirit. Her confidence in her spirit guides faltering – she would later renounce her belief in the reality of the Martian and Hindoo visions – she became convinced that Flournoy was spying on her and railed about him to friends. She took up religious painting, but in a fit of paranoia refused to let any of her paintings be exhibited or photographed. Claiming to have ‘suffered much’ from the perfidy of men – she never married and (apart from Léopold) seems to have had a loathing for the sex in general – she died in 1929 at the age of 68.

What to make of it all a hundred years later? In his elegant, erudite, intermittently irritating Introduction to the new Princeton edition of From India to the Planet Mars, Sonu Shamdasani, historian of psychoanalysis and editor of several works by Jung, presents the story of Flournoy and Hélène Smith as a kind of Post-Modern allegory of a fascinating yet ultimately malign encounter between mental science and spiritualism at the turn of the century. In their ‘encounter with the séance’, he suggests, male scientists like Flournoy discovered both a sexual and an epistemological threat. Precisely because the spirit medium challenged patriarchal protocols so thoroughly – claiming powers of insight and self-expression conventionally granted to men alone – she had to be ‘contained’ within the evolving masculinist discourse of psychiatry. In the ensuing confrontation between the adepts of the new psychology and the (mostly) female proponents of spiritualism, women like Hélène Smith, whose subversive shape-shifting made a mock of business as usual, could hardly escape undamaged.

True, Shamdasani is willing to credit Flournoy with some striking achievements: with developing a model of the unconscious that at once antedates and complements some of the better-known formulations of Freud, and with articulating the concept of a ‘hidden creative self’ that greatly impressed the Surrealists, and Breton in particular. And he acknowledges that clinicians have come in recent years to value the originality and brilliance of the Swiss psychologist’s speculations on cryptomnesiac memories, even as the peculiar mental aberration known as Multiple Personality Disorder reaches epidemic proportions in late 20th-century Western societies. If Hélène Smith were alive today she would undoubtedly be classified, pace Ian Hacking, as a ‘multiple’ – with Léopold, Simandini, Marie Antoinette and the rest as secondary personalities actualised by some mysterious concatenation of intrapsychic causes.

But Flournoy is also in some degree the villain of the piece: an archetype of the Arrogant Psychiatrist, obsessed with a Helpless Woman, onto whom he projects his own unresolved conflicts about sex and the psyche. Thus we learn that Flournoy may have ‘failed to comprehend’ his own emotional transference onto Smith, or the manifold ways that he perhaps exploited her in his ambitious quest for knowledge. He sought to ‘taxonomise’ the ‘museum of all possible phenomena’ he found in her, Shamdasani writes; yet when she resisted, he was ‘haunted’, even unmanned, by her enigmatic image. At the end of From India to the Planet Mars Shamdasani appends a fiercely hostile essay by the French feminist writer Mireille Cifali, who accuses Flournoy (along with another male colleague, Lemaître) of pushing the entranced Smith – by dint of incessant, neurotic questioning – into increasingly distressed and dissociated states. ‘By reading the minutes of the séances,’ Cifali intones, ‘we remain struck with astonishment’ as Flournoy and crony seek to make of the medium ‘a true puppet, a pure object of observation’.

The famous image of the French psychiatrist Charcot grotesquely manipulating the body of a swooning female patient before a crew of male students – or of a gloating cartoon-Freud tormenting a befuddled and resentful Dora – seems to hover over the proceedings here, prompting Shamdasani towards the inevitable post-feminist, post-Foucauldian conclusion: in the pitched battle between male empirical science and female occultist rebellion, women like Smith were essentially victims, their fragile dreams of transcendence obliterated under the cruel, analytic, masculine gaze.

Yet the work itself resists such fashionable circumscription. After reading From India to the Planet Mars William James told its author that ‘you and Delboeuf are the only worthy successors to Voltaire.’ The compliment is apt, for Flournoy’s book is fundamentally a work of satire – an ironic assault on human pretension in the great Enlightenment tradition of Candide or Micromégas. To ideologise over it is to miss its central charm: that while launched as scientific case-history, it is also a brilliant and uncompromising salvo against unreason. Perhaps the most meaningfully ‘feminist’ response to it in the end is simply to acknowledge it as such, even as we see Smith’s visions for what they were: the nonsensical divagations of a psyche puffed up with conceit and self-deceiving to the point of monstrosity.

The work operates as a mock-encomium or ‘praise of folly’, with Flournoy himself an ironically self-deprecating narrative presence throughout. Absent here is the sometimes cheerless dogmatism of Freud: even in the most devastatingly sceptical sections, Flournoy’s manner is one of exaggerated courtesies and arch feigned deference to the ‘ladies and gentlemen’ of the ‘spiritist’ persuasion. Explaining the ‘psychogenesis’ of Léopold, he warns readers averse to such speculations simply to ‘skip’ the offending passages. Accused of being unable to see ‘the supernormal ... plainly before my eyes’, he politely acknowledges that ‘it is, of course, to be regretted, but then it is I alone who will be in disgrace on the day when the truth shall be made manifest.’ And he positively revels in pretended embarrassment when forced to allude to his own starring role in some of Smith’s séance-dramas. Conscious of the ‘honour’ of being appointed the uncouth yet impressive ‘Asiatic potentate’, Prince Sivrouka, he asks the reader’s pardon for calling attention to ‘the immodest role which has been imposed upon me in this affair against my will’.

Yet his greatest ironies are reserved for Smith herself, whose grand ‘subliminal romances’ supposedly rival the visionary creations of the ancient bards and hierophants. Smith is repeatedly described as a ‘genius’ and ‘poet’ (during certain trances, she ‘feels compelled to speak in distinct rhymes of eight feet, which she does not prepare, and does not perceive until the moment she has finished uttering them’.) She is a maker of semi-divine ‘comedies’ and ‘beautiful subliminal poems’; and the scraps of strange handwriting she produces are like passages out of long-lost mystic ‘books’.

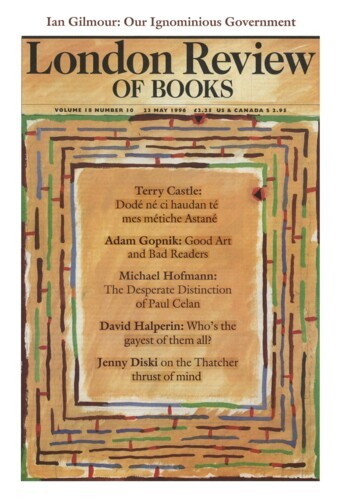

Breton took such comments seriously, educing a connection between Smith’s automatisms and the experimental arts of the Fin de Siècle and beyond. ‘What is Art Nouveau,’ he asked in The Automatic Message, ‘if not an attempt to generalise and adapt mediumistic drawing, painting and sculpture to the art of furniture and decoration?’ And at times one can see – just barely – what he means. Smith’s hallucinatory paintings of various Martian scenes – one is reproduced on the cover of From India to the Planet Mars – have the effulgent colour schemes, flattened perspective and burgeoning floral devices of turn-of-the-century poster art; her rendering, while entranced, of the abstract, curliform Martian alphabet looks like a kind of gormless imitation Klee. In turn, the entire Martian tableau, with its fanciful rocket-cars, wizards in funny hats and flimsy-theatrical ‘extraterrestrial’ backdrops, sometimes brings to mind certain pioneering cinematic images of the period, such as the playful, intentionally hilarious moon-landing sequence in Georges Méliès’s 1902 Le Voyage dans la lune.

Yet it’s impossible to take Flournoy straight, and not only because he so often casts doubt – delicately yet damningly – on Smith’s veracity. After asking her about De Marlès’s history of India, the book in which he finds several Hindoo visions reproduced almost word for word, he praises the ‘indomitable and persevering energy’ with which she denies any knowledge of the book or its contents:

It must indeed be admitted that the idea of the passage in question having come before the eyes or ears of Mlle Smith through any ordinary channel seems a trifle absurd. I only know in Geneva of two copies of the work of De Marlès, both covered with dust – the one belonging to the Société de Lecture, a private association of which none of the Smith family nor any friend of theirs was ever a member; the other in the Public Library, where, among the thousands of more interesting and more modern books, it is now very rarely consulted. It could only have happened, therefore, by a combination of absolutely exceptional and almost unimaginable circumstances that the work of De Marlès could have found its way into Hélène’s hands; and could it have done so and she not have the slightest recollection of it?

I acknowledge the force of this argument, and that the wisest thing to do is to leave the matter in suspense.

What he really thinks of Smith’s disavowal is glintingly apparent: in the exquisite ‘almost’ slipped in before ‘unimaginable circumstances’, in the quaintly anthropomorphised image of the book somehow ‘finding its way’ into Smith’s hands, in the parody of pedantic retreat in the last sentence.

For all of her stunning ‘artistry’, Flournoy intimates, Smith is a colossal waster of her own and everyone else’s time. She aspires to a kind of Wagnerian gigantism: individual séances go on for an exhausting six or seven hours (she is likely to extend them further if sitters dare to fidget or wonder aloud about getting their suppers); she likes to work in a Wagnerian multiplicity of expressive forms – babbling, crying, gesticulating, scrawling messages and drawings, singing snatches of ‘Indian’ melody and so on. Yet the somnambulistic Gesamtkunstwerk is really a Gesamtkitschwerk. After a while, Flournoy hints, the ‘sham’ Orientalism begins to cloy; the visions of Marie Antoinette start to look like the ‘plotless’ maunderings of a not too bright schoolgirl; and even mysterious Mars begins to pall:

All things become wearisome at last, and the planet Mars is no exception to the rule. The subliminal imagination of Mlle Smith, however, will probably never tire of its lofty flights, in the society of Astané, Esenale and their associates. I myself, I am ashamed to acknowledge, began, in 1898, to have enough of the Martian romance.

Ars est longa – but vulgarity is even longer.

Visions such as Smith’s, Flournoy insinuates, clog up the human field: solipsistic in essence, they leave no room for authentic dialogue or connection. They are an affront to empathy: a parody of communication rather than the real thing. Flournoy was prepared to go a long way on a human level with Smith, and some of his comments on her overwhelming emotional neediness – as in the following passage on the Marie Antoinette fantasy – are undeniably touching:

In themselves, Mlle Smith’s royal somnambulisms are almost always gay and joyous; but, considering their hidden source, in so far as they are the ephemeral and chimerical revenge of the ideal upon the real, of impossible dreams upon daily necessities, of impotent aspirations upon blind and crushing destiny, they assume a tragic signification ... The daily annihilation of the dream and the desire by implacable and brutal reality cannot find in the hypnoid imagination a more adequate representation, a more perfect symbol of an emotional tonality, than her royal majesty whose existence seemed made for the highest peaks of happiness and of fame – and ended on the scaffold.

Yet even for Flournoy, one suspects, Smith remained profoundly unlovable. Infatuated with her own ‘gift’ – by which she made herself into a grotesque – she had nothing left to give.

Henry James, who may have known of Hélène Smith through his brother’s interest in her case, saw a kind of obscenity in the lurid manoeuvres of the somnambulist: his depiction in The Bostonians (1886) of the young ‘seeress’ Verena Tarrant convulsing subtly, almost orgasmically, before a group of fascinated observers, is one of the most troubling images of female self-degradation in 19th-century literature. James also knew what many recent social historians of the period seem determined to disallow: that spiritualism – from Katie King and the Fox sisters to Eusapia Paladino and Madame Blavatsky – was a moral, political and aesthetic disaster for women. Rather than prompting any new respect for women’s rights or capabilities, as some scholars have suggested, the spiritualist movement simply reinforced age-old stereotypes about female idiocy, irrationalism and emotional opportunism. Women, like Smith, who turned to the spirit world out of a narcissistic craving for attention, ended up making everything worse for the rest of us.

There are no photographs of Smith in From India to the Planet Mars: as Flournoy notes, she refused to allow any pictures of herself ‘either in her normal state or in that of Léopold’ to appear in the book. This is to be regretted, although she was surely wise (for once) to do so. Has anyone ever noticed the sheer squalor of the mediumistic performances captured in late 19th and early 20th-century séance photographs? In many of these photos, such as those showing the famous Boston medium ‘Margery’ (later exposed as a fraud by Houdini) materialising pieces of fake ectoplasm, the effect is almost pornographic. Margery’s face is puffy and contorted, her body grossly distended, the placenta-like substance that is supposed to be the ectoplasm a disgusting rubbery white blob emerging from under her dress. Hélène Smith knew better, but still not well enough.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.