In the late Twenties, the paternal grandfather of Dimitri, a close friend of mine from Thessaloniki, decided to leave Novorossisk, the Russian Black Sea port. The Soviet Government had ended the NEP, the experiment with small-time capitalism that would be replaced by the Five-Year Plan and collectivisation. The growing pressure of Stalinism persuaded him that the business skills which he had acquired in Istanbul and Trebizond would be better employed in Greece. He succeeded in moving to Drama.

There was no room for Dimitri’s grandfather in the cities or towns of northern Greece. The region was still coping with hundreds of thousands of refugees from Anatolia and eastern Thrace, victims of the Treaty of Lausanne which had regulated the great population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923. So instead of continuing his career as an entrepreneur, he was given a little patch of land and told to become a farmer. In 1941 the Bulgarians stormed through Thrace and eastern Macedonia and he sought refuge in the Italian-controlled region of Macedonia, where the occupation was considerably less harsh. Dimitri’s father was sent to Athens for safety and nearly died there, along with the tens of thousands who failed to survive the merciless winter of 1941-2. For all that, Dimitri’s grandfather made the right decision when he left Novorossisk. His sister, who stayed, survived a number of pogroms before being deported to Siberia in the mid-Thirties. She spent three decades in miserable internal exile before the Greek Government rescued her during Khrushchev’s capricious thaw.

Dimitri’s maternal grandmother was a Bulgarian. She, too, lived close to the Black Sea just outside Edirne (Adrianopolis) and under the provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne she, too, was shifted westwards to the region of Drama. Here she eloped with a Greek doctor, who was arrested by the Bulgarians in 1941 and sentenced to death (largely because of his nationality). His wife pleaded with the local commander, playing on her Bulgarian nationality, and he was given a reprieve. They moved to the Danube delta. After the war, they returned to Greece to escape the Communists in Bulgaria. Here the grandfather was promptly arrested on suspicion of being an Elam-Vougaris (a Greek Communist supporter of Bulgarian/Slav Macedonian expansion). He was shipped to the island of Thasos, where Communist guerrillas and sympathisers were forced to live under atrocious conditions.

The story of Dimitri’s family probably sounds familiar to Neal Ascherson, who must have encountered dozens of similar cases when researching his book. There are cities, towns and villages in the hinterland of the Black Sea and to its west on the Aegean where much of the population can boast of such expulsion.

Dimitri’s grandfather was in Novorossisk when Ascherson’s own father was aboard the Emperor of India, a British warship, which was anchored just off the port in March 1920 preparing to assist in the evacuation of General Denikin’s White Russian forces. The decision of Captain Joseph Henley to accept this devastated army was one of the few commendable British interventions in the Civil War – Deniken’s men would have faced certain death at the hands of the oncoming Red Army.

In the summer of 1991, Ascherson travelled to Moscow for the World Congress of Byzantologists and then went on an excursion with other delegates to the Crimea. On the night of 18 August, he was in a bus on the road from Sevastopol to Yalta. ‘At the Foros turn-off, there was a confusion of lights,’ he writes. ‘An ambulance was waiting at the crossroads, its blue roof-beacon throbbing and its headlights on. But there was no accident to be seen, no broken car or victim. For an instant, as we swept by, I saw men standing about and waiting. As the darkness returned, I wondered for a moment what was going on.’ The next morning the Byzantologists learned that a Committee of National Salvation had taken power in Moscow. Ascherson immediately understood that he had witnessed the arrest of Mikhail Gorbachev, who was spending his summer vacation in his Crimean dacha. Back in Moscow, he followed the heroic defence of the White House by Yeltsin’s supporters and the consequent defeat of the coup.

This is not a history of the Black Sea, as Ascherson anticipates by omitting the definite article from the book’s title. Clearly, this body of water into which five major rivers flow, including the Danube, deserves a thorough political history but that will have to wait. The crucial role it has played in modern European history has today been largely forgotten. At the end of the 18th century, after an age of imperial Russian longing, Catherine the Great assumed complete military control of the northern Black Sea and the Crimean peninsula. From here she hoped to put into effect her grandiose scheme of ending Islamic rule in Constantinople and restoring a Byzantine Empire in the spiritual home of the Orthodox Church.

Catherine’s messianic plot drove the foreign policy of St Petersburg for more than half a century until Russia’s defeat at the hands of France, Britain, Turkey and Sardinia in the Crimean War. That baffling conflict did not, however, signal the end of the struggle for the Black Sea, which continued to lie at the heart of 19th and early 20th-century disputes between the three mighty but failing empires – the Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman. All three competed for southern and eastern Romania, then known as the Danubian Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, which included the great prize of the Danube delta. Were Russia to control them, St Petersburg would enjoy unimpeded strategic access to the Balkans.

Yet not even the Danubian Principalities could compete in importance with the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, the two little necks of water which separate the Black Sea from the Aegean. How Russia’s monarchs, diplomats and naval commanders longed to sail without let or hindrance into the warmth of the Mediterranean. The Turks, however, were not alone in being disturbed by the prospect. The British and French would never countenance it. Russia fought five long wars, from the reign of Catherine the Great until the First World War, for the prize of the Black Sea. It was an obsession which not only brought about the fall of tsarism, but hastened the crash of Ottoman Turkey and the Habsburgs.

Like the Balkans before 1991, the Black Sea now hibernates in Western consciousness. Indeed the terrible war, still unresolved, between the Abkhaz and the Georgians, a conflict cynically manipulated by Moscow, barely generated a yawn in the West. Perhaps this is because the Russians no longer have the capacity or the inclination to reopen the Eastern Question in its 19th-century form by pushing towards the Bosphorus. Perhaps we have already grown tired of the interminable wars which stretch along the old imperial borders from Tajikistan to Chechnya into Azerbaijan and Armenia, through Georgia up towards Moldova and across to Bosnia and Croatia.

To unlock the mystery of creativity, cultural confluence and violent conflict associated with the Black Sea, Ascherson has eschewed conventional history. In its place, he trudges gamely around archaeological sites, some famous, some profoundly obscure. His ruminations on the bones and artefacts of long-extinct peoples drift effortlessly from their ancient history into our millennium and back, from Herodotus to Lermontov, and from the Zaporozhe Sich of the Cossacks to the loners on the Oregon trail.

He possesses a great ability to distinguish real meaning, however obscured by surface detritus, from stories which dazzle on the outside but on deeper investigation reveal very little. Volodya Guguev, a man in his thirties from Rostov, ekes out his living as a disc-jockey. But before the end of Communism, he had found fame as an archaeologist after excavating the skeleton of a young second-century Sarmatian princess and her exquisite jewellery:

She had given him her treasure which, had he been a wicked man, could have been melted down and transformed into enough bullion to buy him a Manhattan penthouse and a life of leisure. She had given him her faith, a puzzle which might, if he chose, preoccupy the rest of his days. In the end, when there was nothing else left at the bottom of the pit, she had given him what was left of her 20-year-old body. Not quite all her bones were there. Some of the very smallest phalanges, the most delicate finger-tip bones, were missing. I saw that this was distressing to Volodya, and we did not pursue it. But his younger brother Yura, one rainy day at Tanais, showed me the colour video of the excavation at Kobiakov 10, and mentioned that he and his brother were divided on this problem of the phalanges. His own view was mat they had been gnawed off and removed by mice soon after the burial, something fairly common in chambered graves without coffins. Volodya, however, did not accept this. He preferred to think that the finger-tips had been ritually severed just after death, perhaps in some ceremony to exorcise the living from the touch of the dead. He could not bear the idea of the mice.

In today’s Eastern Europe, there are countless stories of professors selling carpets and doctors setting up fast-food stalls. No other that I have heard comes close to the poignancy of Ascherson’s tale about Guguev and the princess.

The only conceivable criticism I could make of this book concerns Ascherson’s extended investigation into Adam Mickiewicz’s sojourns in Odessa and Crimea as a young man and in Istanbul, where he died. The great father of Polish romanticism spent a period of bohemian leisure in Odessa just before the 1826 uprising of the Decembrists. Here he dallied with Karolina Sobanska, the mistress of the chief of the Tsar’s counter-intelligence organisation in the city. Mickiewicz was convinced that Karolina was at heart a Polish patriot, although Ascherson has no difficulty exposing her extreme pro-Russian views, which bore all the hallmarks of the recently converted. The problem doesn’t have to do with Ascherson’s telling of the story but with his parallel affection for Poland. Notwithstanding his caveats about avoiding a linear history and the undeniable fact that Mickiewicz enjoyed a special relationship with parts of the Black Sea coast, the struggle of the Polish soul and state-to-be in the 19th century seems a distant companion of the Black Sea.

I would have preferred to be regaled with similarly weird tales about Alexander Ypsilantis, the Greek officer in the tsarist army who in 1821 led the abortive uprising in the Danubian principalities against the Ottoman Empire. Or Tudor Vladimirescu who raised a chaotic rebel force, initially in support of Ypsilantis, before he became a proto-Romanian nationalist destined to meet a sticky end. Ascherson apologises for the lack of attention which the Romanians and Bulgarians receive in this book. The history of these two peoples cries out for somebody with Ascherson’s skills as a storyteller. As he knows, the Poles have plenty of advocates.

His opening analysis of the symbiotic relationship between the Greek settlers on the northern littoral of the Black Sea and the Scythian nomads, who glided back and forth like ghosts between the plains of the interior and the coast, is masterly. It culminates in an explanation of how Athenian scholars and dramatists categorised these two peoples as ‘civilised’ (the Greeks) and ‘barbaric’ (the Scythians). In this Ascherson detects the first primitive tools of European colonialism and the Occident’s sense of superiority.

Anybody who has stopped in Istanbul, Izmir, Odessa, Poti or Trabzon will join in his lament for the Pontic Greeks, obliterated after three millennia during a few callous decades of the 20th century. But it is in his scintillating little essay about the Lazi that Ascherson tackles the paradox of nationalism.

The Lazi are a people of some 250,000, who live almost hermit-like in a tiny corner of north eastern Turkey. They speak a Kartvelian language related to Georgian and Mingrelian. In order to survive, they have avoided defining themselves in modern terms. They are, as Ascherson calls them, ‘a pre-nationalist nation’. They do not want to discover their roots nor to demand their rights. Yet in the Sixties a determinedly eccentric German, Wolfgang Feuerstein, came upon them, learnt their language and set about codifying it into written form. Ascherson visits Feuerstein in his curious Black Forest retreat and is convinced of the German’s impeccable motives in wanting to preserve a precious nugget of difference which would otherwise be submerged by the influence of television and the centralising pressure of the economy.

Where does this journey end? Common-sense, wringing her hands, cries desperately that one thing does not have to lead to another. A decision to write a school-primer in a certain language does not have to lead to demonstrations, broken heads, sedition trials, petitions to the United Nations, the bombing of cafés, the mediation of powers, the funeral of martyrs, the hoisting of a flag. All the Lazi enthusiasts want is to stabilise their memories, to take charge of their own culture. That is not much, no provocation. Logically, the journey should stop there – a short, peaceful journey to a more comfortable place within the Turkish state.

But the rougher the journey, the further it goes. In 1992 Feuerstein’s alphabet was seen for the first time on student placards, in an Istanbul demonstration. Early in 1994, a journal named Ogni, written in Turkish and Lazuri, was published in Istanbul by a group of young Lazi. The editor was arrested after the first number, and now faces charges of ‘separatism’. A second issue of the journal appeared a few weeks later. It called, more clearly than before, for an end to the assimilation of Lazi culture. One of the publishers said: ‘A new age has dawned!’

Cadmus, first king of Thebes, brought the alphabet to Greece. But he also planted dragons’ teeth, which sprouted into a crop of armed men.

In these three paragraphs, Ascherson identifies with tremendous economy the essential contradiction of modern European nationalism. It still thrives, as he points out, ‘whether in the open-hearted, modernising form of the 1989 revolutions or in the genocidal land-grabs in Bosnia and Croatia’. There is no attempt here to resolve the contradiction; rather a sense that ‘the sovereign nation-state is beginning to grow obsolete.’ It is possible that we are witnessing if not the end then at least the taming of nationalism in Western Europe. It remains an open question whether the globalisation which is domesticating nationalism will amount to an improvement. Even if it does, it will take many, many years before the trickle-down reaches the Black Sea. ‘My sense of Black Sea life, a sad one,’ Ascherson writes, ‘is that latent mistrust between different cultures is immortal.’

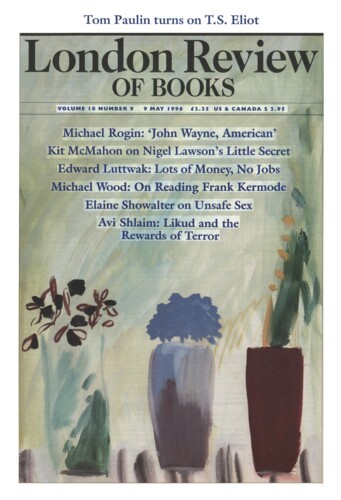

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.