It was an extraordinarily long premiership – indeed the longest of the century by a considerable margin. In part, this was because the Opposition was divided, its members seemingly incapable of suppressing their personal disagreements and policy differences so as to co-ordinate and concentrate their attack. But the premier’s longevity was also due to a high degree of political professionalism and ruthless single-mindedness. Critics were shut out of the Cabinet and state patronage was exploited in an unprecedentedly partisan way. Favours were distributed to those sections of the press which supported the regime. Direct taxes on wealth were reduced in favour of indirect taxation, hurting the middle and lower classes, but beguiling the wealthy. The resulting dissatisfaction, in Scotland, the big cities and among intellectuals, was neutralised by the vagaries of the electoral system.

Naturally, some claimed that the Premier was interested only in power and profit. But this was a woefully inadequate verdict. The Premier genuinely believed that the Opposition threatened Britain’s prosperity and stability, even perhaps its very survival. And many ordinary Britons fervently believed this too. So, in the end, the Premier was not toppled by mass revulsion, nor even by Parliamentary opponents. It was bitter men from the Premier’s own party who were in at the kill, the impatient young, together with those no longer young whose ambitions had been too long frustrated. But even the loss of power had its compensations. There was a peerage and a fortune. The Premier’s children, too, had been enriched by one means or another. Despite the many who hated him, he died in bed.

For I refer, of course, to Sir Robert Walpole, prime minister from 1722 to 1742, architect of the Whig supremacy, hammer of the Tories. His long tenure of power reminds us that Britain’s much-vaunted two-party system has in the past often given way in practice to something approximating to a one-party state. For the past century or so, especially, the pendulum of power has not so much swung from one side to another in a regular fashion as remained fixed for long periods of time in the Conservative camp. Conservative or Conservative-dominated administrations were in power for all or most of the time between 1874 and 1905, between 1916 and 1945, between 1951 and 1964, and again after 1979. It is worth pondering the fact that this marked supremacy of the Conservative Party for more than a century has coincided in Britain with two other momentous developments: the achievement of mass democracy with the Reform Acts of 1884, 1918 and 1928, and irreversible economic and imperial decline.

Nor is this last remark merely waspish. The history of 20th-century Europe as a whole shows that a sense of decline, and in particular of economic disarray, has often been conducive to the success of right-wing regimes, not least in the inter-war period. And there were not wanting in Mrs Thatcher’s Cabinets perceptive souls who detected in her style of government glimmers of far less savoury right-wing popularists from the recent past. It was Alan Clark (he of the dog called Eva Braun) who drooled over her ‘personality compulsion, something of the Führer Kontakt’. And it George Younger, then Secretary of State for Scotland, who remarked of her post-Falklands address to the Scottish Conservative Party in 1982, that it reminded him of ‘the Nuremberg rally’. Countries which believe themselves to be in a mess are easily attracted to authoritarian leaders, especially those who tell them that their decline is not irreversible, but is rather caused by malign elements in their midst.

Putting Thatcherism in its British and European historical context is important if we are to assess it in a measured and accurate fashion. It is all too easy – because she is a woman – to treat her premiership between 1979 and 1990 as sui generis, as something altogether extraordinary, as distinct from a remarkable but, in political terms, by no means unprecedented achievement. This misperception has informed both the appearance of and reactions to this volume of her memoirs. On the one hand, Thatcher secured a uniquely generous advance from her publishers, far more money than a male politician from any Western slate would be likely to command. On the other hand, the initial reviews tended to be sour, not just because the book is over-long and often turgid, but also because reviewers had, erroneously, allowed themselves to anticipate something utterly special. Yet the real historical value of this book is that it helps us to understand the construction and success of a certain kind of right-wing popularism in a century when the Right and popularism have more often than not gone together. Thatcher’s gender certainly mattered. But it was chiefly important because it became, interestingly, part of what made her brand of Tory popularism work.

Superficially, it must be said, the book gives little away. As reviewers have noted, its tone is relentlessly impersonal. Much of it gives the impression of being ghosted. And the determination to stick (however intelligently – and it is intelligent) to public affairs gives rise very easily to sentences at once bathetic and, unconsciously, very funny. ‘I shall never forget the weeks leading up to the 1981 Budget,’ she, or someone else, confides breathlessly. What saves it is Thatcher’s almost child-like inability to distinguish between the world as she perceives it and the world as it actually is. At one level, this means that she gives herself away to a degree that makes her seem almost, almost, endearingly vulnerable. (‘When I arrived in Washington I was the centre of attention.’) At another, we are given valuable in sights into the terrible simplicity of her views. Here, for example, is her mystical conception of capitalism: ‘The free market was like a vast nervous system, responding to events and signals all over the world to meet the ever-changing needs of people in different countries, from different classes, of different religions, with a kind of benign indifference to their status.’ It is what might be called the ‘magic pudding’ view of the market. How ever many of us sit round the table and tuck in, the pudding will remain intact and we will all be satisfied. And here is her solution to Liverpool’s vicious unemployment: ‘I had been told that some of the young people got into trouble through boredom and not having enough to do. But you had only to look at the grounds around those houses with the grass untended, some of it almost waist high, and the litter, to see that this was a false analysis.’ So there we are then. Let them cut grass.

But dismissiveness, though easy, should be controlled. For what also emerges from a close reading of this text is the formidable anger that Thatcher was able to draw on to appeal, far more effectively than liberal or socialist politicians ever did, to those myriad Britons who feel disadvantaged or excluded in some way. A consummate insider in terms of prolonged access to real power, she never lost her sense of being an outsider, and this was the key to her success. Being female was part of the parvenu self-image but so, too, was being lower middle-class: ‘In the eyes of the “wet” Tory establishment I was not only a woman, but “that woman”, someone not just of a different sex, but of a different class, a person with an alarming conviction that the values and virtues of middle England should be brought to bear on the problems which the establishment consensus had created. I offended on many counts.’

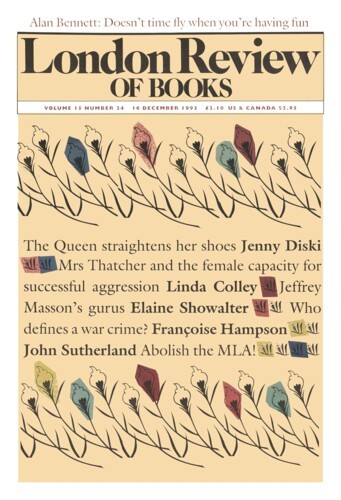

As a card-carrying Conservative, Thatcher is of course impatient of both feminism and gender-based analysis. ‘More nonsense was written about the so-called “feminine factor” during my time in office than about almost anything else,’ she storms. But her virulence gives her away. Her gender, together with the chip she carried on her shoulder about her social origins, always informed her style. Witness her delight in humiliating important males. These could be the men of her own party, as when she notes how hopeless Geoffrey Howe and Michael Heseltine were when they accompanied her on a visit to Reagan in 1985. ‘I did not bring them again,’ she remarks, for all the world as though they were a couple of incontinent pet dogs. But foreign statesmen could fare little better. That same year, Brian Mulroney and Rajiv Gandhi scurried to show her ‘their best efforts’ on a draft communiqué on South Africa, ‘Alas, I could not give them high marks’ is her verdict. Of course, this is only her version of events. But that’s what makes it revealing. Anyone interested in women’s studies ought to read this book, because it illuminates what has usually been ignored and often denied: the female capacity for successful aggression. Neil Kinnock always used to claim that his ability to attack Thatcher at Prime Minister’s Question Time was sapped by natural chivalry in the face of a woman. This was self-serving nonsense. What defeated him, and so many others, was the fact that she was a much better fighter.

Being female in a world of men shaped her success in other ways as well. Like all highly ambitious career women so positioned, she could never relax into her position or take it for granted, and so worked desperately hard, much harder than her male rivals were likely to do. The indefatigable professionalism on display in this book is always impressive. There are the four hours’ sleep a night – at most. And how could one not warm a little to someone who understands that public speaking is an art involving precise preparation: ‘I used to mark up the text with my own special code, noting pauses, stress and where to have my voice rise or fall.’ There are the clothes: that ability constantly to re-invent her appearance which being female allowed her. Though being a woman and middle-aged also meant being fat. These memoirs leave no doubt that Thatcher savoured her public dinners, especially in France, with predictable results. References to corsets crop up in many of her speeches quoted here. So, more self-consciously, does the explanation of why she likes tailored suits: ‘They also have the advantage of gently passing by the waist.’

Femaleness, then, was an enormous asset, as it usually is if a professional woman is able to surmount the initial barriers and prejudice and reach a level where almost everyone else is male. Yet, as is often pointed out, Thatcher did little, except symbolically, for her fellow women. True, she insisted that the Civil Service should insert women on its various short lists of the great and the good. But this was part and parcel of her delight in bashing the upper middle-class establishment. When it came to her own Cabinets, her chosen policy advisers, her chief backers in the press and academe, the people who garnered the gongs, women hardly ever got a look in. Women appear in this book overwhelmingly as wives, as typists, as indispensable personal assistants (‘Crawfie’), and as cheerful West Indian canteen ladies. But their ranking in Thatcher’s Conservatism is best summed up in two of the book’s black and white photographs.

At the top of a page we are shown Margaret, Denis and the Cabinet at the Carlton Club, celebrating her tenth anniversary as prime minister in 1989. She is the only woman present. And since the Carlton still does not allow women members, she had in fact to be made an honorary male member for the occasion. Shown below these notables, against a background of oil paintings, wall sconces and marble floors, is a very different room and a very different company. It is Finchley that same year, and Margaret and her constituency workers are having a knees-up beneath the false beams and insulated ceiling tiles of the local club. And here there are women aplenty. Nice ladies, with carefully permed hair, crimplene dresses brought out of mothballs, and sequined evening bags. As Beatrix Campbell and others have shown, such women are the vital, beating heart of virtually every Conservative constituency organisation. They were and are indispensable to the Party – but as devoted subordinates. And under Thatcher that’s where Tory women largely remained – at the bottom of the pile. Enjoying her exceptionality as a woman on top, she was never moved to adulterate it.

The fact that she partook of what American feminists call the ‘Queen Bee’ complex, relishing her power while taking care that no one else of her kind came near it, is important in assessing Thatcherite politics more broadly. Quite simply – and as with most popularist leaders in the past – there was always a glaring disparity between her demotic language and what she did for the masses in fact. In this book, as when she was in office, she claims again and again that hers was the people’s party. ‘We were the only ones in touch with the popular mood,’ she boasts. Labour and the SDP might take their colour from high-flown intellectuals, but the audience she sought was ‘the rising working and lower-middle class’. In terms of the political language she employed, and in terms of the votes she won, this is entirely valid. Working-class Toryism has been a marked phenomenon in Britain since the late 19th century: it became still more prominent in the late 20th century under Thatcher. And her opponents actually contributed to her popularist success by the way they attacked her. Foolishly, they called her a grocer’s daughter. They mocked her reputed Philistinism. Oxford loftily refused her the honorary degree which it had invariably bestowed on previous premiers who had been old boys. And, as in this case, far too much was made of her sex. Until it learnt better, Labour’s slogan was ‘Ditch the bitch.’

In short, the Opposition did almost as much as the Sun newspaper to help Margaret Thatcher present herself as being at one with your average disadvantaged and disgruntled Brit. Yet the obvious and far more insidious attack that could have been levelled against her personally was for some reason rarely ever made. Preacher of hard work, enterprise, and pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps – and identifying herself repeatedly with those who did exactly that – Thatcher was in fact something of a fraud. In reality, she had married – not made – money. As Hugo Young has pointed out, ‘Margaret Thatcher bore some resemblance to the Conservative landed gentry, the element in the Party which she later came most powerfully to despise. She may not have inherited a private income, but she married an alternative to it. Financially she belonged to the leisured classes.’ It is entirely characteristic that her memoirs make no mention of this awkward fact. Instead, we get class-conscious denunciations of her party’s ‘false squires’, and questionable claims that she, by contrast, understands the mass of the people because she has shared their experiences: ‘I did not feel I needed an interpreter to address people who spoke the same language.’

For language, like style, was the key, or rather the smokescreen. There can be no doubting that many of Thatcher’s policies were extremely popular. But there seems also little doubt that the lynchpin of her three administrations, lower direct taxation, catered more to the already prosperous minority, than to those more modest but striving masses whom she invoked so eagerly in her speeches. A rich woman herself (now, with her husband, worth over sixty million pounds according to one estimate), she made it very much easier for those of her countrymen who were already very rich. Just occasionally, the awareness that this was so bobs near the surface of her text. There is, for example, a telling anecdote of the lead-up to the 1983 election. She pondered long and hard about the precise day for polling that year because she did not want it to coincide too closely with Ascot: ‘I did not like the idea of television screens during the final or penultimate week of the campaign filled with pictures of toffs and ladies in exotic hats while we stumped the country urging people to turn out and vote Conservative.’ Of course she didn’t. It might have blown her cover, deconstructed her popularist language.

In other words, the angry popularism which came so easily to Thatcher because of her sex and social origins was more a matter of rhetoric and style than substance. Something very similar could be said about another major component of her appeal, her patriotism. This is, of course, fervent and superficially unproblematic. Pride in a country called Britain shines through her account of the Falklands war, which is authentically gripping. And it was her gut patriotism (as well, again, as her sex) which allowed her to upstage Labour’s gesture in 1986 of replacing the red flag as the Party’s logo with a red rose. She promptly stormed into the Conservative Conference at Bournemouth wearing a rose in her corsage. ‘The rose I am wearing is the rose of England,’ she cried, thereby commandeering the enemy’s symbol and turning it to her own empowerment. Equally striking, one might think, are her caricatures of foreigners. The French are over-intellectual and garrulous; Germans are regimented, aggressive and consumed by self-doubt; and, with some few exceptions, Italians are poised between confusion and guile. The EEC’s ‘quintessentially un-English outlook’ dismays her.

Yet the harder one looks at Thatcher, the less she seems (as distinct from speaks) like Joan Bull. To begin with, and as she more or less admits, she is not really British at all, but Southern English, Grantham being long since put behind her. Wales appears in the index to this volume only once. Her direct contact with Scotland appears to be confined to attending Conservative conferences north of the border. And her frustration at her party’s failure here leads her into another of her unconscious revelations. ‘In Scotland,’ she writes, ‘the Left, not the Right, had held onto the levers of patronage.’ It is her one admission that a ruthless deployment of patronage has, elsewhere in the UK, been vital to her and her party’s longevity. For obvious partisan reasons, Northern Ireland receives much warmer treatment than Scotland. Though even here one senses that this may be because the commitment involves struggle and is therefore ipso facto attractive, and not just because Unionism is in her blood.

Moreover beneath the fervent, and doubtless deeply-felt patriotic rhetoric, was always an absolute commitment to international capitalism. Indeed it was the patriotic rhetoric which often permitted the internationalism. Few other premiers, Conservative or Labour, could have got away so easily with the commitment finally to breach British geographical insularity and build a Channel Tunnel. By the same token, she oversaw the sale of erstwhile public utilities to foreign companies without a qualm – and again without being seriously attacked on nationalist grounds. Though some foreign Capital is better than others. Western Europeans are always hard to take, even when they buy up British water companies. Confronted by the Japanese yen, she melts into a degree of cultural relativism which deserts her in the presence of the deutschmark or the franc. Japan, she says, in all seriousness, must have its ‘sensitivities understood’.

Her other soft spot is for the United States of America, or rather for certain aspects of it. And, again, this special relationship illuminates the ambiguities of her patriotism. She insists here, as she always did, that there was nothing untoward in allowing America to station cruise missiles on this island without pressing for the dual key which would have given British governments a say in their possible deployment. Nor, apparently, can she conceive that there are British patriots who – without being anti-American – find being the United States’ ‘principal cheerleader in Nato’ (her own description of her role) a savagely limited and increasingly out-dated foreign policy option. British autonomy was always to be asserted against ‘the ways and wiles of the Europeans’, but not against the Americans. And this was not just because the United States was a superpower. She liked it that way, and could contemplate no other possibility.

Yet in the last years of her premiership, the earth was beginning to move under her feet in this as in so many other respects. The last chapters of these memoirs are a chronicle of her growing unease and isolation. Bush replaced the sympathetic Reagan, and made it clear that he regarded Germany, not Britain, as ‘America’s partner in power’ in Europe. She was unhappy both about the speed of Germany’s reunification and its close alliance with France, an axis she had always feared but had in fact accelerated by antagonising both powers. There was too much talk of federalism, even in her own Cabinet. The economy sagged (this was Nigel’s fault). And perhaps some of the disparities between her language and her actions began – just occasionally – to register even with her.

She had believed that ‘the level of unemployment was related to the extent of trade union power,’ and had decisively broken that power. Yet unemployment by the late Eighties was nonetheless rising fast. She had been sure that poverty was the natural outcrop of socialism’s dependency culture. Socialism had been scotched (in every sense): yet the proportion of Britons in poverty had increased. The streets were violent because ‘the state had been doing too much.’ Under her, the state had ostensibly done less: yet violence increased. She had trumpeted the enterprise culture with conviction. Yet she still felt obliged to send Ken Clarke to run the Department of Health because ‘he was unlikely to talk the kind of free-market language which might alarm the general public.’ Was it disillusionment at these strictly muted results of her policies that ground her down, making her at the end of her career, as at the end of this book, increasingly desert her own scruffy and divided homeland? Was this why she preferred to concentrate instead on trips to Washington, Paris, and those newly-liberated Eastern European states which still clutched at her political message?

Certainly she seemed strangely out of touch with events at the end, insisting on departing to Versailles on 18 November 1990, instead of staying in London to fight the leadership ballot out in person with Michael Heseltine. By the time the first ballot had gone against her and she had returned, it was too late to recover. Too many long-humiliated Conservative males were out for her blood. There was nothing left for Margaret Thatcher but to leave Number Ten on 28 November, Crawfie wiping away the mascara-stained tear on her cheek.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.