4 January. On BBC’s Catchword this afternoon, one of the questions apparently consists of anagrams of playwrights. Mine is Annabel Tent. Nobody guesses it.

A joke about the Queen Mother who in an old people’s home finds herself not treated with the proper respect. She approaches a nurse:

QM: Don’t you know who I am?

Nurse: No, dear, but if you go over and ask the lady at the desk she’ll probably be able to tell you.

14 January. Most of the headlines this morning quote Bush’s remark that they have given Saddam Hussein ‘a spanking’, a homely term which nicely obscures the fact, nowhere mentioned, that people were killed, spanked in fact to death. A couple of days ago one of our peace-keeping troops was shot in Bosnia and he is pictured everywhere. Maybe the Serbs or the Croats, or whoever it was shot him, think this was just a bit of a spanking too.

16 January. Now the papers are full of the latest scandal, the bugged phone call between the Prince of Wales and Mrs Parker-Bowles. I read none of it, as I didn’t read the earlier Diana tapes, not out of disapproval or moral superiority, just genuine lack of interest. I wish it would all go away. Sickened by the self-righteousness of the newspapers, which, though it takes a different form, is as nauseating in the Independent as it is in the Sun. Depressed too by the continuing corruption of public life, ex-members of the Government moving straight onto the boards of the ex-public utilities they have helped to privatise and reckoning to see nothing wrong in it. Meanwhile the Government keeps at it, relentlessly paring and picking away at the proper functions of the state; ‘lean’ is how they like to describe it, but it’s gone beyond lean; now it’s more like the four-day-old carcass of the Christmas turkey. Then an item today about babies born without eyes in Lincolnshire makes me want never to read a paper again and go and live in the middle of a field.

20 January. Collected by the New Yorker and taken to be photographed by Richard Avedon, now a grey-haired faun of 72 who says he’s bored with taking snapshots in the studio (this morning Isaiah Berlin and Stephen Spender) and wants to photograph me outside. ‘Outside’ means that eventually I find myself perched up a tree in Hyde Park. Avedon’s assistants bustle round with lights, Avedon himself scarcely bothering to look through the lens, just enquiring from time to time where the edge of the frame is. He explains he wants me to seem to sit on the branch but actually to lean forward into the camera at the same time. I try.

‘You’re game,’ says Julie Kavanagh of the New Yorker.

Actually I’m not game at all, just timid; and, short of taking my clothes off, ready to do anything, even climb trees, rather than be thought ‘difficult’.

A propos of which is Whitman’s description of himself to Edward Carpenter: ‘An old hen … with something in my nature furtive’.

2 February. Late for a final rehearsal for the tour of Talking Heads I rush out of the house on this bright spring-like morning to be confronted by a large pile of excrement on the path. Thinking it’s a dog, I swear and am about to go in and get a bucket to swill the path when I see that shit has been smeared on the car, and the paper whoever it is has used to wipe his or her bum has been carefully stuffed into the door-handle. I swill the flags, wash the car, and returning home this evening, wash it again with Dettol, reflecting that if my mother were in a state to know of this she would never get into the car again, would want it sold or at the very least a new door fitted. Wonder if the person who did the shitting is the same person who stove in the car window on Saturday night but decide this is paranoia.

8 February, Newcastle. Coming back to the hotel from the dress rehearsal, I call in at the cathedral, the parish church as it must have been until about 1900. A grand medley of church and state, the army and the professions, it’s an old-fashioned place too in that you’re not blitzed with information, exhibitions and outreach as soon as you set foot in the door. Here is Collingwood, Nelson’s admiral, and an 18th-century general in the Deccan Rifles, dead on the voyage out; surgeons and solicitors of the town, neat, kneeling Tudors, plump Augustan divines and an atmosphere of piety, property and Pledge never quite caught by anyone, even Larkin, whose life I must get on and review, I wanted Forty Years On to be like this cathedral, studded with relics and effigies, reminders and memorials, half-forgotten verses and half-remembered hymns. Everything fits: the crypt chapel nicely restored in the Thirties, the memorial to Danish seamen dead in the war, the brasses rubbed to extinction before a lavish Twenties altar rail; time and what it has deposited.

11 February, Yorkshire. Am periodically sent statements of profits (sic) by Hand Made Films, which produced A Private Function. Each year the loss escalates and now runs at some two million pounds for a film that cost two-thirds of that. Write back suggesting they submit the statement as an entry for this year’s Booker Prize and saying that if it won they’d be able to convert the prize money into a loss too.

Remember at supper in Giggleswick that, when I was a boy in Armley, the clothes horse was called the ‘winter edge’, actually the ‘winter hedge’. W. suggests, poetically, that it was because, laden with clothes, it would look like a hedge covered with snow. More plausibly, it was because in summer clothes could be spread on the hedge (though not in sooty Armley) and in winter on the horse. The other name for it, remembered by W.’s 85-year-old mother, is ‘clothes maiden’.

16 February. A child lured away by two boys in Bootle and found battered to death and run over by a train. A boy is taken in for questioning and crowds gather outside the house, jeering and hurling stones, so that the family have to be taken away to a place of safety; the boy is later released. The ludicrous Mr Kenneth Baker blames the Church, and in particular the Bishop of Liverpool, David Sheppard, probably because he’s the only socialist in sight.

22 February. A large crowd gathers outside Bootle Magistrates Court, to jeer as the vans carrying the two ten-year-olds accused of the toddler’s murder are driven away. One man eludes the police cordon and manages to bang on the side of the van, and six others are arrested. Yesterday Mr Major appealed for ‘less understanding’, as indeed the Sun does every day of the week.

The single and peculiar life is bound

With all the strength and armour of the mind

To keep itself from noyance.

Come across this said (I think) by Rosencrantz. As so often with Shakespeare you wonder what sort of life he led, how he came to know this. It takes in most of Larkin’s life.

A regular from Arlington House walks down the crescent, stiff as a ramrod, upright, respectable. By his side and pressed as firmly into the seam of his trousers as the thumb of a Guards sergeant major is a can of McEwens lager.

10 March. The Independent pursues its campaign against John Birt over his tax arrangements. On another page it boasts its acquisition of Jim Slater as its Stock Exchange commentator.

13 March. To Weston to see Mam, who is dulleyed, expressionless, absent. The sun is hot through the blinds and the radio full on. ‘My,’ says a nurse (who’s not really a nurse), bending over the wreck of some ex-Somerset housewife, ‘it’s 12.30. Doesn’t time fly when you’re having fun!’ Downstairs comes an uninterrupted lamentation from some caged creature. ‘Well,’ says the nurse, spooning another dollop of rice pudding into a gaping mouth, ‘what I say is, if you’ve got lungs why not use them?’

20 March, Yorkshire. Late on Saturday afternoon I drive over to the Georgian Theatre at Richmond and do my piece. Half the audience in dinner jackets, part of a group paying extra to dine afterwards with the Marquis of Zetland, thus raising more money for the Dales Museum. Nobody comes round and since I’ve cried off the dinner, I come away feeling unthanked but also obscurely pleased, as it shows I’m just the entertainment, below stairs the proper place for the actor, and which I’m in favour of if only because the opposite can be so dire. So while half the audience are dining at Aske with the Zetlands I am sitting in the Little Chef at Leeming Bar having baked beans on toast. Which is what I prefer so it isn’t a grumble. But catch myself here doing a Larkin (or being a man) – i.e. claiming I don’t want something, then chuntering about not getting it.

9 April, Good Friday. ‘It’s Good Friday!’ shouts the ginger-haired young man who presents The Big Breakfast, as if the goodness of the day were to do with having a good time.

What nobody seems to say (and what I didn’t say) about Larkin’s idea of the artist, lonely, unpossessed and unpossessioned, is that it’s both romantic and conventional, Pearson Park was a garret.

15 April, Lady Thatcher back on the scene, lecturing the world about Bosnia with ‘Bomb the Serbs’ her solution. She doesn’t begin by saying, as any fair-minded person would. ‘I admit I supported the Serbs to start with,’ Just hoping no one will remember that (and having some glib answer if they do). Most people would also say that the fewer arms there are on the market the easier these conflicts would be to settle, and that anyone whose family is involved in arms-dealing would do better to pipe down about the moral issues. Nobody points this out, least of all to her.

18 April. A 70th-birthday party for Lindsay Anderson in St Mary’s Church Hall, Paddington. Lindsay in one of his presents, a silk dressing-gown (‘I’m wearing it to show that I am quite happy to direct Noël Coward if asked’). A wheelchair has been provided for a 90-year-old guest who hasn’t turned up, so Lindsay commandeers it and is wheeled around the room getting older by the minute. Full of all sorts of people, with showbusiness probably in a minority, and off-hand I can’t think of any other director who’d be given a birthday party like this, and with such lovely parish-hall food, ‘A very English occasion’ is how it would be described. The church hall was built after the parish had discovered that it owned the land on which the A40 fly-over had been built and so was compensated with several millions – a real-life Ealing Studios plot.

11 May. To Weston. Besides the women Mam’s room now has two men, Cyril and Les. Cyril is small and plump with a little secret smile, as if he’s sitting on an egg; Les has a bad chest and does what Mam would once have called ‘ruttles’, i.e. gargles with phlegm. He can’t speak except as part of a routine he does with the cleaner. She says: ‘Les, Les.’ And having got his attention: ‘Boom tee bum bum.’ And Les (sometimes) says: ‘Bum Bum.’ This is as much laughed to and applauded as if he were an elephant that had got on its hind legs.

15 May, Yorkshire. Sitting in the car at Richmond, waiting while R. has a look round, I see out of the corner of my eye a middle-aged woman crossing over towards the car with a broad smile on her face. I assume I have been recognised and am about to be accosted and compose my features in a look of kindly accommodation. Even so I am a little taken aback when the woman, without even knocking on the window, actually opens the car door. Still, I don’t show any surprise; this is a fan, after all. But not merely does she open the door, she gets in, sits down beside me and closes the door. Still I make no protest. She settles herself, then finally turns to me, still smiling.

‘Only in Yorkshire … Bloody Hell! I’m in the wrong car!’ and bolts, running back along the pavement to her by now wildly gesticulating husband.

The person who is really shown up by the story is, of course, me.

Tony Cash tells me that he saw A Lady of Letters done on French TV. When Miss Ruddock is watching the young couple who live opposite her she remarks: ‘The couple opposite just having their tea. No cloth on. Milk bottle stuck there, waiting.’ This has been translated: ‘The couple opposite just having their tea, No clothes on. Milk bottle stuck there waiting.’ It’s the milk bottle that intrigues.

8 June. Man overheard in Oxford Street: ‘Can that cow shop! Jesus!’

18 June. Alan Clark’s Diaries mention being smiled on in the lobby by the Prime Minister. Idly opening Chips Channon’s Diaries I find a similar note, re Chamberlain. Courts do not change whether the court is at Westminster, Versailles or even British Airways, Lord King’s rare smiles presumably a high favour. But that grown men should garner a little hoard of smiles from Mrs Thatcher and find something to comfort them there makes me thankful this dull morning to be sitting at my desk, watching the rag-and-bone man push his cart past the window, his Jack Russell stood eagerly in the prow as if waiting to strike land.

On Any Questions on Radio 4 tonight are Roy Hattersley and Edward Heath, Janet Cohen and Jonathon Porritt. Neither Heath nor Hattersley is a particular favourite of mine but because no one on the panel is extreme in their views, discussion is sensible and without point-scoring and one has the feeling by the end of the programme that the topics have been properly aired and some understanding achieved. Contrast this with Question Time on BBC 1 last night with Norman Tebbit, Shirley Williams and some unidentified industrialist. Tebbit played his usual role of a sneer on legs, snarling and heaping contempt on any vaguely liberal view and the discussion, which was no discussion at all, was rancorous and rowdy and left all concerned as far from enlightenment and understanding as they had been at the start. It is Any Questions of course that is the exception, Question Time with its shouting and ill-temper very much the norm. And for this we have to thank the ex-Mrs Thatcher and her cronies; they have un-civilised debate and denatured the nation.

25 June. Walking in the park we pass some young black boys playing football. One gets a shot at goal which the goalie, in the way of goalies, does not think the so-called defenders should have allowed him. However he manages to save the ball and throws it back into play, shaking his head and saying, as a reproof to his own team, ‘’Ave a word, ’ave a word.’ I take this to mean ‘Pull your socks up’ or as they would say in Yorkshire, ‘Frame yourselves.’

Having espoused the attitudes of the Thirties the Spectator now seems to be aping their style: ‘Her mind was as sharp as any I have known.’ Thus Charles Moore on Shirley Letwin. Buchan is alive and editing the Sunday Telegraph.

11 July. An ex-prisoner turns up at the Drop-In Centre in Parkway. He is violent and the Centre telephones Social Services for help, who tell them to send him round. The Centre does so, phoning to say that he’s on his way and that he’s armed, though not saying with what. It’s actually a syringe filled with blood, which he claims is Aids-infected, and he makes his way through Camden Town brandishing this at horrified passers-by. At Social Services he says it’s not his own blood but that he bought it at Camden Tube Station for £1, and when a social worker bravely tries to persuade him to give it up he takes the cap off as if he’s cocking a gun. Eventually he is coaxed into a taxi, the social worker goes with him and en route for the Royal Free persuades him to give up the syringe, which is then flung out of the window.

Had Harriet G. not told me the story I would put it down as an urban myth. But it isn’t, the most chilling part of the saga the syringe changing hands for £1 as a profitable investment. The social worker who took him to hospital deserves the George Medal, but he’s more likely to be dismissed by Mrs Bottomley as just another ancillary worker bleeding (sic) the Health Service dry.

18 July. Lord (ex-Chief Rabbi) Jakobovits is in favour of genetic engineering to rid the world of homosexuality. I wonder whether he’s always been in favour of medical experiments.

11 August. Neville Smith sends me a menu from Virginia Woolf’s, a restaurant and bar in the Russell Hotel, which tells prospective diners that Virginia Woolf was ‘a modernist writer’, a member of the Bloomsbury Group ‘which used to meet at 46 Gordon Square where topics for discussion were Philosophy, Religion and the Arts’. Dishes include Jacob’s Burger (a burger in a creamy mushroom sauce). Mrs Dalloway’s (sauce poivre, pink and green peppercorns, cream and brandy) and Orlando’s (hot chilli sauce). As a dessert you can have ‘Virginia’s favourite: deep-fried banana with vanilla ice-cream, real maple syrup and cream. Irresistible.’

Carol Smith says: ‘Well, if that was her favourite I’m not surprised she sank like a stone.’

25 August. Asked to write the entry on Russell Harty for The Dictionary of National Biography, I duly send it off. A card from Ned Sherrin saying he has been landed with Hermione Baddeley on the same principle – i.e. if he didn’t do it nobody else would. His contribution had been returned to him because it lacked the full name of her second husband, something she didn’t know herself as she always referred to him by his initials.

Shot of a dead whale being slowly winched up a ramp.

Men with satchels of knives move in and slit it open.

Titles come up: ‘The Art of Biography’.

6 September. Work in the morning, get my lunch, cold chicken and beetroot, then bike down to Bond Street. I look in Agnew’s, buy some soap in Fortnum’s and end up in the Fine Arts Society, where there is an exhibition of American prints. I chat to two of the partners about F. Matania, an illustrator I have remembered from my childhood and whom I’d like to know more about. Then I get on my bike, having spent a civilised afternoon, the kind that leisured playwrights are supposed to spend. Except that when I get home T. says: ‘What are those red stains on your chin?’ And all the time I have been dallying in Fortnum’s and idling in Agnew’s and chatting in the Fine Arts Society my chin was covered in beetroot juice so that I must have looked as it I’d been sucking an iced lolly.

15 September. There are three reporters. The woman is smartly dressed, hair drawn back, hard-faced and ringing the bell at this moment (and now rattling the letter-box). They have been outside the house for two hours, since eight o clock this morning, and though there has been no sign of life or anything to indicate I am at home, madam periodically strides briskly up to the door and rings the bell as if it were the first time she has done it. She is at it again now and clip clip go her little heels as she trips back down the path. Across the road her companion waits, a solid middle-aged man with bright white hair and glasses, a sports outfitter perhaps, the secretary of a golf club, even chairman of the parish council, though there is something slightly seedy or lavatorial about him but nothing to suggest he is a reporter or a photographer on the Daily Mirror. I’m mildly surprised that both of them read the Mirror; they sit in their car drinking coffee and looking at their own paper, pigs wallowing in their own shit. The third, slightly forlorn figure is a balding young man in a Barbour who rang the doorbell last night to say he was from the Daily Mail, the first time I was aware I had done anything to attract any attention. I closed the door in his face then and now he is back but with no car to sit in he stands disconsolately on the pavement, picking his nails. Meanwhile the phone rings constantly.

All this is because in a profile in the New Yorker a week or so ago I made a few unguarded remarks about my personal life. These are apparently reprinted and amplified in this morning’s Mail, as if I had approached the paper anxious to come clean.

‘Hello?’ The balding young man is calling through the letter box.

‘Hello, Mr Bennett. Can I have a chat? I just want to clear up one or two misconceptions.’

Periodically the chairman of the parish council pokes his little lens through the car window and takes yet another photograph of the mute house.

Around four the shifts change and Ms Hardface and the Chairman of the PCC go off, leaving a bearded young man to do duty for them both.

‘I don’t want to make your life a misery,’ says one of the notes put through the door.

I think of George Steiner who asked Lukács how he got through so much work.

‘House arrest, Steiner. House arrest.’

16 September. A.N. Wilson thoughtfully weighs in, this time in the Evening Standard, comparing me with Liberace and Cliff Richard and saying I have been boasting about my sex life. ‘You silly prat’ is what I feel, wondering how anyone who writes for such a rag as the Standard feels in a position to say anything about anybody. The littleness of England is another thought. All you need to do if you want the nation’s press camped on your doorstep is say you once had a wank in 1947.

26 September: Six days in France, much of it in drenching rain, driving round Provence. Most towns and villages now meticulously restored – Lacoste, Les Baux, Aries, Uzès, the cobbles relaid, the stone cleaned and patched, everywhere scrubbed and made ready – for what? Well, for art mainly. For little shops selling cheap jewellery or baskets, for galleries with Provençal pottery and fabrics, bowls and beads and ‘throws’. Better, having done the clean-up, to put a machine-shop in one of these caves, a butcher’s where a butcher’s was, a dry-cleaner’s even. But no, it’s always art, dolls, kitchenware, tea-towels. And people throng (myself included), les Baux like Blackpool.

Arles is better because a working place still and with a good museum of monumental masonry, early Christian altar pieces, Roman gravestones and beneath it a labyrinth of arcaded passages that ran under the old Roman forum. The Musée Arlaten, on the other hand, is rather creepy, the walls crowded with primitive paintings of grim females, Arlésiennes presumably, and roomfuls of 19th-century folkish artefacts, collected under the aegis of the trilby-hatted poet Frédéric Mistral whose heavily moustached image is everywhere. Many of the rooms contain costumed dummies which are only fractionally less lively than the identically costumed attendants, some of them startlingly like Anthony Perkins’s mother in Psycho.

Then to an antique fair in the middle of some zone industrielle, every stall stocked with the appurtenances of French bourgeois life: great bullying wardrobes, huge ponderous mirrors and cabinets of flowery china. For the first time in my life I find myself longing for a breath of stripped pine.

12 October, Baltimore. Edward Kemp, the National Theatre’s staff director, goes into a diner.

‘How do you like your coffee?’ asks the waitress, who is black.

‘White, please,’ said Edward.

‘Excuse me?’

‘White … with milk’. The explanation not-withstanding the waitress marches away into the kitchen refusing to serve him.

Another waitress comes out, also black.

‘All I want,’ says the hapless Edward, who has not twigged, ‘is a white coffee.’

‘No,’ says the waitress. ‘You want a brain.’

26 October. The queue outside the Post Office this morning trails right up past the (now closed) Parkway Cinema, where half a dozen people are sleeping in the doorway. Sunley, who demolished the St James’s Theatre back in the early Sixties, still at it thirty years and a clutch of knighthoods later. I suppose Mr Major would cite the re-development of the cinema as evidence of ‘the recovery’.

8 November. The Government is preparing to sell off the forests and nature reserves. I wonder whether it ever occurs to the 14-year-olds who staff the Adam Smith Institute that such seemingly unrelated policies have something to do with the rise in crime and civil disorder generally? Paid to think the unthinkable, do they not see that unless the state is perceived as benevolent, a provider of amenities, parks, art, transport even, then how should it demand respect in its prescriptive and law-giving aspect? Particularly when the law is represented by Group 4.

24 November. Some junior minister blames the Bulger murder on the Church of England’s failure to teach the difference between right and wrong. Poor Church. It’s supposed to hold the Government’s coat (and its peace) while the Government kicks the shit out of society and then it has to take the blame for the damage that’s been done.

28 November, Leeds. Fewer beggars in Leeds than in London though I notice today a young man approach a woman asking for some change.

‘Oh, don’t!’ she wails in a tone so heart-felt it’s as if his necessities are the day’s last straw.

Forty years ago beggars in Leeds had specific locations. Bond Street was patrolled by the smarter prostitutes but also by Cigarette Liz, an old gipsyish woman in half a dozen coats and with a stained tab end always dangling from her lips. Outside Trinity Church on Boar Lane was a man with a flat cap and no legs, his hands resting on what as a child I took to be blocks of Sunlight soap which I thought he was selling, but which were the grips on which he hauled himself along. No one seemed to give him anything, perhaps because, like me, they just thought of him as a feature of the street.

Someone I took for a long time to be a tramp wasn’t at all. Dirty, often drunk, in a greasy overcoat and very Jewish he would hang around the Art Gallery or slump over a book of paintings in the Reference Library where he would be periodically woken up by the staff and told, ‘No sleeping.’ This was the painter Jacob Kramer, an early Vorticist and contemporary of Nevinson, William Roberts and Wyndham Lewis. I had often looked at his portrait of Delius in the Art Gallery without knowing that, like Elstir, this down and out was the painter.

Roberts, who was Kramer’s brother-in-law, was often to be seen in Camden Town in the Seventies. An apple-cheeked man, he looked like a small rotund farmer but wasn’t at all amiable and if one got in his way on the pavement he would unleash a torrent of abuse. Knowing his wife slightly I was once asked back to tea but made to promise that should Roberts appear I was to show no interest in painting. When he didn’t I was both relieved and disappointed.

29 November. In one stratagem for not working today I find myself carefully cleaning off the accumulation of dried ointment from the nozzle of the Vaseline Derma Care hand-lotion dispenser.

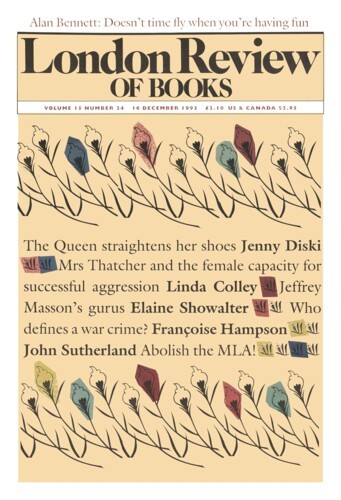

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.