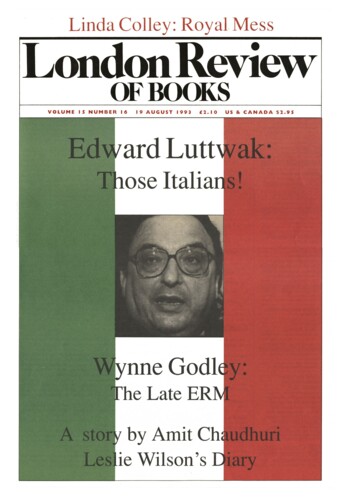

When Gianni de Michelis, then Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Italy, attended a semi-official Nato anniversary conference organised by Washington’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies, and held with some formality at the Palais d’Enghien in Brussels, he was accompanied by a handsome blonde with unspecified duties on the state-owned ENI or possibly the Socialist Party of Italy payroll; a brunette with unspecified duties on the state-owned ENI or possibly the Socialist Party of Italy payroll; several personal political aides (he had added some three hundred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs payroll as opposed to the usual dozen); and a larger train of both diplomats and seconded military officers than any other attending Nato minister or uniformed potentate, including the Supreme Allied Commander, Europe – even though that exalted rank is much noted for the imperial magnitude of its escorting staff.

When Gianni de Michelis, then still Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Italy, attended the semi-official October Conference of the Pio Manzu Research Centre held in some luxury at the five-star Grand Hotel of Rimini (an Italian Torremolinos in the summer, but Fellini-fashionable in the autumn), he brought with him just one very tall brunette with unspecified duties on the Socialist Party payroll, but so many other camp-followers that they half-filled the vast Paradiso disco-restaurant in the Rimini hills, where he celebrated till early morning, as was his wont. (During his tenure, it was an actual part of the duties of Italian embassies everywhere to select a suitable all-night disco when preparing for a ministerial visit.)

When Gianni de Michelis took a break from his duties as Minister of Foreign Affairs, or as vice-president of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Italy, to dine informally in a fashionable restaurant, as he did almost every evening when in Rome, he never sat down without at least a baker’s dozen at his table, including at least one person of the opposite sex with unspecified duties but on a state or Socialist Party payroll; several grateful beneficiaries of his power to appoint senior executives in state-owned enterprises, presidents of state-controlled banks, under-secretaries in government departments, and members of some of the best-remunerated state boards for this, that and the other; and at least one would-be beneficiary of his alleged power to distribute government largesse by way of contracts, a role which included, ex officio as it were, the payment of the routinely colossal bill (a huge 300-pound, six-footer-plus, de Michelis was an expensive guest all by himself, as he never was, for he combined a gourmand’s appetite with a gourmet’s insistence on expensive delicacies and costly labels).

But it was in his own Venice fiefdom that Gianni de Michelis most truly resembled an Oriental potentate. The President of the United States can launch 19,999 thermonuclear weapons against whatever country happens to irritate him, and even the UK PM has the SAS at his beck and call, as well as the odd armoured division, what is left of the Royal Navy, and a few nukes of his own. But both are in every other way pathetically impotent by comparison with de Michelis before all the rules abruptly changed in Italy. He did not have to be in Venice to enrich favourites at will (George Bush could not even keep two of his own sons from bankruptcy) or to have beautiful women in pairs overlook and presumably service his spectacular ugliness (Major, an Adonis by comparison, can only dream of such rewards). But it was only in Venice that de Michelis could be roundly dominant, for there he had to share his powers with fewer of the other ci-devant masters of Italy.

At their more arcane, those powers supposedly ranged from such petty things as the issue of water-taxi licences (as his presumed protégés, the licensees habitually violated the no-wake speed limit with impunity, inflicting lethal damage on Venetian foundation piles), to an allegedly most remunerative influence on the awarding of major government contracts for highways, bridges, port installations, water-treatment plants and suchlike. (His political secretary and formerly inseparable alter ego, Giorgio Casadei, has been in prison for months, charged with receiving numerous mega-bribes; and orders have also been issued for the arrest of his personal secretary, Barbara Ceolin, who has evaded capture so far.)

De Michelis did not, however, lack the kind of power that can be displayed openly, to the naked eye, in true princely fashion. The same Venetians who loudly cursed his exit from the Piazza San Marco court where he was summoned to testify last March on one of very many corruption charges, had for years been his eagerly servile audience at art-exhibition openings, restored-palace inaugurations, prestige conferences, and all otherwise notable gatherings held in Venice. None was deemed a success if Gianni de Michelis did not arrive with his attendant courtesans, aides, media admirers and hopeful petitioners, to speak the speech, in which he would generously instruct artists on art, architects on architecture, economists on economics, town-planners on planning, philosophers on philosophy, and micro-neuro-surgeons on micro-neuro-surgery.

None of this means that de Michelis was the worst specimen of that political class which is now, in its entirety, headed for oblivion, if not prison. On the contrary, he was one of the very best. Not merely cunning in the manner of all successful politicians, not merely clever as better politicians are, not merely highly intelligent, but a man of true intellectual ability, de Michelis was perfectly capable of speaking interestingly on architecture, economics, town-planning, philosophy, and perhaps even micro-neuro-surgery, and of course world politics (nobody could speak usefully about Italian politics). Since the deluge, some of the Italian journalists who most eagerly courted his favour have ridiculed his Mediterranean co-operation scheme, his concept of European integration, his views on North-South relations. Strongly expressed, significantly original, they were indeed controversial ideas, which I for one mostly disagreed with, but they were certainly not trivial ideas. Compared with most of his colleagues in Italy and in Europe, except for Sweden’s Carl Bilt and of course Vaclav Havel, de Michelis stood out as an intellectual giant. Nor has any crime of any sort been proven against him in any court of law, so far. It is possible that he only took money for his party; it is even possible that he took no money at all (though the magistrates must believe otherwise, for why else would they keep his man Casadio in jail to make him talk?).

De Michelis did, however, exemplify the sheer arrogance of Italy’s political class by the eve of its downfall. For along with the transformation of old-style political corruption from the quiet goings-on of the past to the flamboyant corruption of the Eighties, displays of arrogance had become a definite fashion among politicians – they were evidently seen by them as a test of in-your-face electoral machismo. Thus De Michelis liked his hair long and unkempt, and long and unkempt it was. De Michelis liked to be escorted by beautiful women, and by them he was escorted, even at formal state functions. De Michelis liked to disco-dance till he was drenched in sweat, and sweat he did in discos everywhere, even while on official visits abroad.

None of the above is a crime, but all served to proclaim a unique exemption from the conformities to which democratic politicians are everywhere subject. Italians are most broadly tolerant, caring not a fig if a member of parliament or a minister has extra-marital or non-marital affairs, whether hetero or homosexual, or even enthusiastically quasi-pederastic in one famous case. Not for them the prompt disgrace of whoever is caught in a bush with a guardsman. (Italy has its own corazzieri: they, too, are fit young men stationed in the heart of metropolitan temptations with scant pocket money.) Of lesser appetites they are even more tolerant. But Italians do expect a modicum of discretion. And they are sufficiently respectful of foreign opinion to have very much wanted an outwardly respectable foreign minister.

Precisely for that reason, de Michelis made the most of his displays of unrespectability. All you Italians who fear Communism, he was signalling, will have to vote for the Socialist Party if you cannot stomach the Christian Democrats, have no traditional Liberal, Republican or Social Democrat affiliations, reject Neo-Fascism, and refuse to waste your vote on micro-parties. And because you cannot vote for an individual but only for a party, your vote will come to me anyway, no matter what you think, for I am one of the bosses who controls the party secretariat, which draws up the list of beneficiaries of the Socialist vote. So screw you, and all your petit-bourgeois ideas of respectability.

De Michelis had unusual ways of advertising his arrogance, but such displays had become quite common. Some politicians simply preferred overt corruption. Thus Bettino Craxi, the Socialist chief and sometime prime minister, occupied a huge apartment in the very heart of Milan (Europe’s most expensive real estate) while notoriously paying only a piddling rent that would not have secured a dingy room at market prices – and he also kept a sprawling suite at Rome’s Raffaello Hotel which alone cost more than his salary; similarly, de Mita, the Christian Democratic chief and another sometime prime minister, was quite unfazed when it was ineffectually published that he was renting his own huge central Rome apartment at a peppercorn rent thanks to a state-regulated insurance company; while the Naples boss Ciro Pomicino actually showed off his vast multi-million dollar penthouse to the press – a property that he could not possibly have paid for honestly.

All three were first-league players, but by the late Eighties even small-time provincial bosses were not only enriching themselves on a grand scale, but advertising their corruption by showing off newly-acquired palatial villas and yachts. Indeed the climate of Italian politics became such that the rare party hierarch who did not collect vast bribes was tempted to pretend that he, too, was corrupt, for fear of being regarded as a weakling or a fool. Bosses such as Ciro Pomicino were making it perfectly clear that whoever could not pass millions of lire to his teenage son as argent de poche for the weekend, keep a yacht, and generally live in princely style, was unfit for higher office – and a danger to his less foolish colleagues who knew how to milk their offices. Bologna Christian Democrat Beniamino Andreatta, a man of exceptional talent and in the less corrupt past a highly successful minister, had to wait almost two decades and for his party’s final crisis to receive the foreign Ministry. Because he was known to be honest, he could not be trusted to keep his mouth shut by top party chiefs themselves deeply immersed in illegalities of every sort.

Corruption was not the worst sin of Italy’s political class. Worse than the tangenti – the systematic extortion practised on would-be contractors to fill party coffers – even worse than personal money-making by every sort of corrupt practice, was the readiness of many Southern politicians to collaborate with organised crime. Even that ‘many’ minimises, for it averages out the near-universal criminal affiliations of office-holders in the crime belt (Campania, Calabria and Sicily) with the near-absence of the same in other parts of the South (Lucania, Puglie). I once asked an NCO of the Carabinieri why the police did not close down the much-too-big-to-conceal reverse assembly lines of Nocera Inferiors where Fiat Uno and other mass-market cars were turned into spare parts for resale all over Italy. It was, he said, ‘a question of political equilibria’. For it so happened that the Christian Democrat politician who served successive governments as Minister of the Interior, i.e. the police minister, himself came from Nocera Inferiore which, as it happens, is a major stronghold of the Camorra, the Neapolitan version of the Mafia. The equation was simple: the Carmorra delivered lots of votes to the Christian Democrats; the votes made the minister politically powerful within his party; the minister therefore dissuaded the police from acting against Carmorra operations, including the auto disassembly plants. For the same reason, contraband cigarettes, sold very discreetly all over Italy, were sold perfectly openly on the streets of Naples. And of course the drug trade, too, was protected, though not quite as blatantly or fully.

Nor did organised crime reserve its favours for the Christian Democrats. In different parts of the South, the local criminal outfits were allied with the ultra-corrupt Socialists, the otherwise much less corrupt Republicans, the Social Democrats, and the Communists; in some cases, no party was given exclusive support. In the major drug entrepôt of Gioia Tauro in Calabria, for example, the local crime family ruled the municipality through a coalition patterned on the national five-party coalition (Christian Democrats, Socialists, Republicans, Social Democrats and Liberals), although the brothers and cousins did not always remember which party they were supposed to represent.

How did organised crime deliver the votes? What seems impossibly hard, given secret ballots, was achieved reliably enough by inducements (i.e. jobs in the aforementioned disassembly plants), by intimidation (especially in rural areas where it could be guessed who voted for whom), and by mere instruction. For organised crime not only had power but also a degree of genuine authority, derived from its wealth, prestige and – in circular fashion – from its links with the locally strongest party, especially when that party was the Christian Democrat, itself so closely affiliated with that greater source of authority, the Apostolic Catholic Church.

In many Southern towns, the bishop, the crime boss, and local state officials functioned as the spokes of the same wheel of power, whose hub was the Christian Democrat party leader because only he communicated with all of them. In such places the ordinary citizen’s sense of utter powerlessness, much remarked upon by cognizant visitors, was not therefore the result of a millennial apathy (the usual explanation) but rather reflected a bitter realism. To have a building permit for a modest four-room house denied ‘because of the plan’, and then to see permission given for a 24-room villa on the same plot, once it had been acquired by ‘one of them’; to be refused public employment only to see it given to someone else much less qualified; to watch the crime bosses’ henchmen move about town with cellular phones and bulges under their jackets, in full view of uninterested policemen; to have local businesses refuse to buy cheaper/better goods and services because their existing higher-cost suppliers were ‘connected’; to pay protection fees to local criminals and concurrently extortion fees to local officials; to hear of grotesquely over-priced government contracts given to the front-companies of organised crime – all this was part of everyday life in the crime belt.

At bottom, the cause of the criminal alliances of the South was simple. In the rest of the country, big business was at hand as a source of money, if not votes. But in the Southern crime-belt, businesses of any size that are locally owned and headquartered are a rarity – except for the business of crime. And organised crime perpetuated that condition, for its arbitrary power was incompatible with locally-based entrepreneurship (Northern-owned plants paid both protection fees and bribes without a murmur – they were very cheap compared with the colossal subsidies they received).

In Sicily, where along with the sun everything is more intense than on the mainland, ‘political equilibria’ protected not only illegal money-making but also murder on an industrial scale. Salvatore Riina, a royal duke of Mafia, was a wanted man with many outstanding warrants for his arrest – warrants for procuring multiple murders, for example. Yet Riina lived in the perfect comfort of a pleasant villa, often travelling about his business in a chauffeured car. Police road-blocks were very frequent in Western Sicily, yet somehow the police never intercepted Riina. In fact, for more than twenty years they were not able to locate him. Then the shipwreck of the great politicians of Rome began. Riina was promptly arrested. Giulio Andreotti, a minister ever since 1946 and many times prime minister, has now been formally accused of having protected the Mafia. The ex-mafiosi who accuse him need not be believed, literally. The magistrates may need their evidence but the rest of us do not. For Andreotti was openly and very closely associated with Sicilian politicians who in turn were openly and very closely associated with the Mafia.

Alliances evolve over time, in accordance with shifts in relative power. From the Sixties onwards, the rise of the drug trade enormously increased the profits of organised crime (all that was achieved by breaking the French connection – the Marseille drug industry – was to give the business to Sicily and Calabria). Political protection was increasingly bought simply for money: there was no need to deliver votes as well. Moreover, what was being protected was no longer traditional low-key extortion but the delivery of narcotics all over Italy and beyond, with the attendant enforcement of franchises by murder. Having learned to protect the murderers of rival criminals, some Southern politicians in due course graduated to the protection of the murderers of over-zealous policemen, magistrates and specially appointed anti-Mafia prefects, including, most notably, General della Chiesa.

Such extremes were only reached in the worst parts of the crime belt, but everything that happened in the South was in money terms distinctly small-time by comparison with the mega-bribes which, by the Eighties, had become common in the North: the Feruzzi Group alone paid some sixty million dollars in just one transaction in order to have the state overpay by much more for some money-losing plants it sold to ENI.

How did Italian politics reach such depths of iniquity? It all began very purposefully in the Fifties, when money was needed not for yachts and filial Ferraris but to resist the unique power of Italy’s Communist Party. Repeatedly winning more than 30 per cent of the vote, the PCI would not have needed much more to form a governing coalition with left-wing socialists and the small ultra-left party. Even without an electoral majority, the PCI had important instruments of power at its disposal. Its highly disciplined members were regularly deployed in threatening mass demonstrations; their control of Italy’s largest trade-union confederation allowed them to orchestrate devastating political strikes; and their hold on the country’s intellectuals gave them a great deal of influence over public education, the mass media and most cultural institutions.

The PCI also had a great deal of money, both from the rich agricultural, industrial and commercial co-operatives it controlled and from the Soviet Union. It has long been known that PCI-controlled companies raked off commissions from all Italian-Soviet trade deals, but secret Soviet files now opened have revealed that it also received direct grants – which incidentally continued long after the much-celebrated and supposedly final break with Moscow in the wake of the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia. The PCI’s Eurocommunism, supposedly antagonistic to the Kremlin and all its ambitions, was generously financed by the Kremlin – which obviously believed, along with Italy’s anti-Communists, that Eurocommunism was merely a repackaging of the same Leninist product. It was to meet this truly sinister challenge that the Christian Democrats originally developed the methods of covert funding which were to be emulated by almost all other parties, the PCI itself included.

All private money-making aside, Italian politics did not come cheap. At first, covert funds were needed to fight ubiquitous Communist propaganda, which in 1951-3, for example, made Moscow’s charges that the USA was using bacteriological warfare in Korea a ‘fact’ so widely repeated by Communist schoolteachers that it is still believed today by many middle-aged Italians; funds were needed to pay the salaries of party professionals, so as to compete with the army of dedicated Communist cadres active in every town, village and city district; to subsidise anti-Communist trade unions and cultural institutions so that they could challenge their stronger Communist counterparts; and, in the early post-war years of acute poverty, even to hand out food and clothing to the poor in order to diminish the appeal of Communism at source.

During the Sixties, as its ideological fervour waned, a better remedy for the PCI’s power was found by the Christian Democrats: having long since colonised the huge state-owned sector, from the largest Italian industries grouped under the IRI and EFIM holding companies, and the oil and gas and petrochemical industries under ENI, to the RAI’s television and radio; having already shared out the resulting under-the-table payments and myriad political appointments with the lesser parties in its coalitions, the Christian Democrats simply offered a share to the PCI as well – which accepted with much alacrity. The most obvious sign of this strategic shift from relentless containment to co-optation was the three-part division of RAI television: Italians could watch Christian-Democrat slanted news on the highest-budget RAI Uno (leading star: the Pope), the Socialist worldview on the middle-budget RAI Due (Bettino Craxi) and the Communist version on the less well-funded RAI Tre (Ho Chi Minh, Mao, Arafat). The sharing out of illicit revenues, extortion on government contracts and state jobs for the boys was only marginally more discreet. And of course organised crime followed suit, with the usual consequences: in one Sicilian case, the provincial PCI headquarters became a subsidiary of the local Mafia family.

Aside from their share in the division of huge illegal spoils, both Communists and the more convinced Catholics among the Christian Democrats also had to be careful to disguise something else: their remarkable ideological alignment once Cold War affiliations became less significant. Both favoured an authoritarian, highly centralised and economically dominant state, because both were fundamentally opposed to free enterprise (a Protestant aberration), free thought, free sex, free art and indeed anything free at all, diverging only in their preferred inspector-generals – bishops in one case, commissars in the other. In effect, this species of anti-liberalism (Cato-Communismo) became the dominant operational ideology of post-Sixties Italy. Thus, paradoxically, no country was a more obedient ally of the United States, and in no country outside the Communist sphere was the state more powerful within the economy and society – in direct opposition to the ideals that the United States was forever seeking to promote.

The successful inclusion of the PCI completed the fashioning of Italy’s political class, for a social class in the strict Marxist sense is what it had indeed become: cohesive in protecting common interests notwithstanding party and factional distinctions, and clearly separated from ordinary Italians not exempt from the law. The current reworking of the PDS (the renamed PCI), into an anti-corruption crusade is a skilfully executed piece of effrontery, but it does not fool many Italians: certainly in the North the PDS is melting down.

The transformation of the anti-Communist struggle into a working alliance removed the original justification of illicit party funding. But by then it was much too late. Each party had acquired its own huge and hungry internal bureaucracy, hordes of expectant camp-followers and electorally significant supplicants. And corruption had corrupted what had been an almost entirely disinterested party corruption into the near-universal personal corruption of party bosses big and small.

The Italians are unusually well-known and well-liked among the peoples of the world – and with very good reason given their abundant talents and remarkable kindness. By contrast, Italian politics have always been poorly understood and much disliked – and with good reason too, given their impenetrable complexity and disreputable character. That is the reason, no doubt, for the widespread misunderstanding of the drastic changes now taking place in Italian politics. Only in the last few months have the outlines of twin revolutions been recognised in what has been happening day by day. One is the legal revolution being carried out by those magistrates who are belatedly visiting the same law on all Italians, instead of exempting politicians and their friends, as in the past. And the second is the federalist revolution championed by the Northern Leagues, which one way or another will de-centralise Italy, as all larger democratic countries have long ago been de-centralised.

The sudden flood of revelations of large-scale corruption in political parties, ministries, state-owned firms, and the government of provinces and cities was at first grotesquely misunderstood to mean that the Italian people had quite recently become spectacularly corrupt, for reasons unknown. But soon it was recognised that what was new was only the exposure of long-established corruption, and that it was not a people that was corrupt but rather a specific political system, controlled by party bureaucracies headed by rival cliques or irremovable lifetime leaders.

That is the system, and the culture of corruption, that the 2500-plus investigations of politicians and their friends, the several dozen detentions-the-better-to-interrogate, and ten suicides are now demolishing in many (not all, as yet) parts of Italy. It seems that having invented so much else in politics, including the very concept of the ‘balance of power’, Italians have now invented a new sort of non-violent revolution, which by entirely legal means, is eliminating a whole political class possessed of extraordinary power and wealth.

The meaning of the sudden emergence of the Northern Leagues was also badly misunderstood at first. Aware of the wealth gap between North and South, Americans initially accepted the characterisation of the Leagues as a sort of Italian Poujadisme, motivated by a selfish refusal to help the South, as well as by a regional equivalent of racism. The claim of the Italian political establishment that the Leagues were nothing more than an ephemeral protest movement, destined soon to disappear, was widely believed.

The mere existence of the Leagues, however, directed attention to the structure of the Italian state. In a world in which all larger democracies are already federal or significantly de-centralised – even in famously unitary France regional councils have been granted increasing powers – the exceptionally centralised Italian state has become a glaring anomaly. Only Japan is almost as centralised, but in its case the demand for local autonomy is reduced by the formidable efficiency of the public administration, which provides high-quality services at moderate cost, from the world’s best system of public education to local offices staffed by quick, courteous and well-trained officials.

Once the outside world discovered how little power is left to the regioni, provinces and municipalities of Italy, and that they were in any case captive to Rome-centred national parties, its opinion of the Leagues changed drastically, from contempt to approval. After all, no country is truly local, whether at the ‘state’, Land, county or municipal level. Once seen as racist, reactionary and sterile, the Leagues are increasingly recognised as the liberators of Italy from the Fascist-era centralism which the Cato-Commumst consensus perpetuated. Alongside the magistrates who are demolishing the oligarchy of party princes, lawless magnates and godfathers, the Leagues have become Italy’s true revolutionaries.

As for Italy’s Baedeker bombings, they are not at all surprising. Terrorism is as Italian as pasta, having started its modern history in the struggle against the Habsburgs waged by the bombiferous secret societies. These latest bombs, however, are almost certainly aimed at protecting the disintegrating status quo. Every revolution is resisted by those who derived their power, wealth and privileges from the ancien régime. But normally, the self-interested enemies of the revolution acquire the support of that vast majority of the population which is disgusted by the revolutionaries’ indiscriminate violence. That, of course, is why most revolutions fail.

What has been happening in Italy is certainly a revolution, because an entire political élite is being swept away. But the Italian Revolution – and it is time to call it that – is historically unprecedented, in that it is being carried out by exclusively legal means, not by bloodthirsty mobs or murderous commissars. It is therefore not provoking the usual counter-revolutionary reactions. On the contrary, most Italians fully support the investigations. Far from wanting to stop them, they impatiently wait for corruption to be exposed in those parts of the country and those institutions which have not yet been seriously investigated.

The protagonists and beneficiaries of Italy’s ancien régime have no hope of attracting majority support. They are and will remain isolated. Some have been driven to the extreme remedy of suicide; most accept the inevitable loss of their political power and social prestige and are trying only to keep their dishonest wealth, and to stay out of prison. A few party bosses are still seeking to evade prosecution by manoeuvring in the thoroughly discredited (and soon to be dissolved) Parliament or by enlisting the aid of a President elected by that same Parliament, of media allies who can be blackmailed, and of church figures who long collaborated quite happily with those whom they knew full well to be corrupt. From all of them, we now hear that preventive detention is too cruel (they voted for it in the past), that the investigations have gone on for too long (they have just begun), and that the disruption of the system is too costly for the Italian economy (it was the huge increase in corruption in the Eighties that weakened the economy).

But organised crime was also a great beneficiary of the regime, and its natural form of expression is violence, not last-minute Parliamentary manoeuvres or discredited interventions. Precisely because these particular counter-revolutionaries are so isolated, they are not inhibited by the fear of antagonising public opinion. In that sense the bombs in Rome, Florence and Milan were thoroughly predictable. With the politicians that long protected them now paralysed, with the police at last free to act against them in full force, the criminal bosses have every reason to fear the future. No longer will politicians loudly proclaim new anti-Mafia policies in Rome only to sabotage them systematically at the local level; no longer will they appoint super-investigators only to leave them unsupported when they want to act.

Having lost its really powerful weapon, political support, organised crime is left with only one weapon: terrorism. The logical aim of the bombs is to frighten public opinion, and thereby convey the message that if the investigations stop and the regime is restored, the bombs will also stop. The location of the bombs is also transparently logical: a bomb in a famous place attracts more attention than the same bomb in some obscure suburb. It is theoretically possible that the logical explanation is wrong, that the bombs were placed by others with the same or other motives, or with no rational motives at all. But no credence can be given to the hypothesis of an unspecified foreign intervention, advanced by some Italian politicians in the language of conspiracy favoured by both Catholics and Communists of the old regime.

Actually it doesn’t at all matter who placed the bombs and why. Both the Leagues and the magistrates will undoubtedly continue to press forward, creating the preconditions for a normal state: small, decentralised and reasonably honest. In such a state, crime, too, will become normal, and criminals will no longer dream of influencing Italy’s political life.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.