Week Nought. After months of media discussion as to the likely election date, we were finally put out of our misery: it was to be April. What was rather more of a surprise was the Chancellor’s Budget: no penny off the basic rate of tax, but a new tax band of 20 per cent for the first £2000. Did no one remind him that Labour had tried much the same thing – a 25 per cent band when basic rate was 33 per cent – and that his party had eliminated it? At any rate, the proposal caught Labour with its ideological trousers down, unable to object, without sounding churlish, to the poorest-off workers paying less tax.

Week One. On Monday, 16 March, electioneering proper began. This was the week of the Labour ‘Budget’, which proposed an income redistribution plan of the first order. Money was to be shifted from the pockets of higher-paid taxpayers into the pockets of all pensioners and mothers, and into the social and educational services. The sheer daring of the exercise was breathtaking. Labour appeared to be banking on the altruism of the better-paid in not minding the unplanned-for loss of a substantial portion of their income, though their idea of who constitutes the better-paid seemed a bit out of date, since the increase would begin at under £22,000. It is worth recalling that when the great wage-inflation of the Seventies took many Labour voters into the tax net for the first time, the 1974-79 Labour Government discovered that they objected to paying higher taxes to help the worse-off. The Labour Party might find the same thing happening. They might also find that many of their supporters who are not yet paid £22,000 aspire to be so, and resent higher tax in anticipation. Or Labour might have judged the electorate entirely correctly and the New Jerusalem was at hand.

At any rate, most of the week was taken up with discussions of the two economic plans. It was delightful to watch highly-paid journalists caught between support of Labour’s moral high ground on the tax front and the realisation that their own economic self-interest might dictate otherwise. I must confess that I find the holier-than-thou streak in British political culture a mite off-putting. One needs only to hint that wholly state-run provision of a service might not always be the optimum choice, or even that the more efficient use of what provision there is should be encouraged, and the reaction is that, secretly, you are keen to grind the faces of the poor.

Week Two. I don’t own a television, so I missed the event of the week, which was Tuesday night’s Labour Party broadcast on the Health Service. Thus began the War of Jennifer’s Ear, which raged for three days. The media were clearly bored with economics, and welcomed the possibilities inherent in the situation of a small girl in discomfort. The whole thing rapidly degenerated into farce, however, with reporters bred on the pursuit of Royals turning their talents to finding out who had leaked her name. Reduced to interviewing each other, they realised after three days that no one else was paying any attention.

Where were the Greens? In the 1989 European elections they gained 15 per cent of the vote, providing the first glimmerings of their possible seriousness as a political force in Britain. They then faded away, but were now contesting about 250 seats in this election. Were they keeping quiet about it, or were the media too taken up with the cut and thrust of the three main parties to report what the Greens were saying? When I went to a local bookshop to buy the election manifestos, there was no Green manifesto for sale.

I can’t say the manifestos made riveting reading, but they were marginally illuminating. The Labour Manifesto, at 28 pages of small type and some pictures, cost a pound. The Liberal Democrat Manifesto, at 50 pages of largish type, some pictures and some wide margins, cost £1.50, The Conservative Manifesto, at 50 pages of smallish type and without pictures, cost £1.95. After comparing their respective plans for higher education, it rapidly became clear why most of my academic friends seemed to be voting Liberal Democrat: it would be in their professional interest to do so, since this was the only party to address the problems of higher education in their manifesto. Labour concentrated on schools, while the Tories promised to continue to make us leaner and fitter. The Liberal Democrat Manifesto was by far the best-written, while the Tories seem to have dumped into theirs every idea anyone in the Party ever had: my favourite was the promise on page 41 to plant a new Midlands forest. I decided not to buy the SNP Manifesto for the simple reason that it cost a fiver.

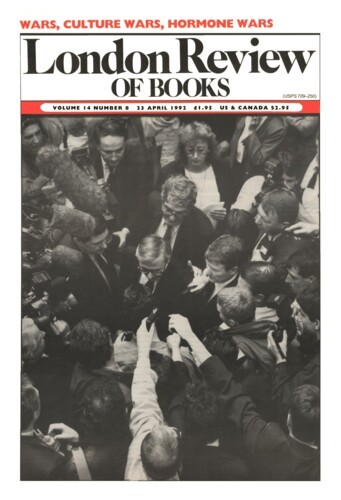

Week Three. This week things finally began to get interesting. On 31 March, opinion polls gave Labour a substantial lead, up to 7 per cent, and the City panicked: on Red Wednesday share prices plummeted over a hundred points (although the exchange rate of the pound hardly moved). That night Neil Kinnock addressed a large and responsive audience at a rally in Sheffield, and his triumphalism symbolised Labour’s growing conviction that they were going to win. Indeed, the assumption began to dominate commentary both on the radio and in the papers. Practically alone of his party, John Major reacted positively, grabbing the now-famous soapbox in Luton and thereby returning to his Brixton political roots. This was the signal for an outbreak of patronising journalism by writers who clearly didn’t know what they wanted. There had been continuing complaints that the election was intensely boring because the candidates, Major especially, were not contributing to any debate, but merely travelling from one tedious photo-opportunity to another; then when Major actually got up in the middle of a hostile crowd and spoke to them, this was not considered interesting or even democratic, but somehow demeaning. It was also, given the threats of the IRA to disrupt the election, positively dangerous, and must have given the Special Branch nightmares.

On Sunday I went out and bought all of the papers to see what they were saying about the election. It was a revelation. The quality papers aired their prejudices – none of this rubbish about impartial reporting – but in a relatively restrained and literate manner. The tabloids, however, were awe-inspiring in their awfulness. Labour has often complained that they are unfairly treated by the press, and I can now see their point. An hour with the News of the World, the Mail on Sunday, the Sunday People and the Sunday Express left me feeling distinctly queasy.

More enjoyably, I settled in front of a neighbour’s television with a bottle of his wine to watch David Dimbleby interview all three of the main party leaders. It was illuminating. Kinnock hardly seemed the same man as the one on Today in Parliament: he was in control both of himself and of the interview. Paddy Ashdown likewise was very impressive, and Major handled Dimbleby’s probing questions with very little difficulty. Either the wine had eroded my critical powers, or lack of exposure to television makes me too susceptible to the visual image: I thought they were all wonderful.

Week Four. My experience on Sunday convinced me that I should make more of an attempt to tune in to the television version of the election and not depend wholly on Radio 4 and the papers. Alas, ringing around several shops in South Oxfordshire turned up no one who was willing to rent me a set for less than a year. One event of the previous week to which I had paid scant attention had been ‘Democracy Day’ on 2 April, when Charter 88 and the Economist had organised 101 open meetings with candidates around the country to discuss constitutional change. At roughly the same time, attention was focused on the Liberal Democrats’ increase in the polls. The upshot seems to have been the crystallisation of Labour’s decision publicly to point out that the door was open for discussion about proportional representation. Suddenly Major took it seriously, and began to warn against changing the voting system in any shape or form. Indeed, his warnings about the danger to the constitution and to the unity of the United Kingdom now represented one of the two main themes of the Tories. The other, of course, involved a redoubling of efforts to scare the electorate about the results of Labour’s tax plans if they gained office.

And it may have paid off. Labour had been in the lead according to the polls from the beginning of the campaign, but the final polls indicated that the Tories were catching up. It was all remarkably reminiscent of the 1970 Election, when Labour had been in the lead throughout, but the final polls indicated a Tory surge. In the current case, the creeping-up of the Conservatives seemingly could not have been at the cost of Labour: their standing in the polls had scarcely changed since the beginning of the election. The only alternative was that it prefigured a collapse in support for the Liberal Democrats.

Election night. A thoughtful friend showed up at my door lugging her spare portable television. I set it up in the dining-room, and turned on Radio 4 in the kitchen: listening to both, I scurried from one to the other. When Roy Hattersley was being interviewed on the box, for example, I retired to the kitchen to listen to Brian Redhead and David Butler. At least I have now seen a swingometer, although since the set was black and white, I only learned the following day that the arrow was neon purple. I have also seen David Dimbleby trying to build bricks with straw, when by midnight he still had only four results and was hard pushed to find enough of interest to say about them to keep his audience awake.

But the wait was worth it. The Basildon result had been a shocker, but it just might have been an isolated event. What was undeniably fascinating was watching the projected result change integer by integer, as swings stubbornly refused to go up to the required 8 per cent to enable Labour to sweep to victory. At 10 p.m. the BBC was predicting a hung Parliament. By 12.30 a.m. the BBC best-case projection was still a hung Parliament, but with the possibility of a Conservative majority of three. By 2.45 a.m. the prediction was a Conservative win, and thereafter the projected majority grew. When I finally staggered to bed just before 4 a.m., I think that the projected majority was 13.

The evening was full of excruciating moments. Why did the Liberal Democrats have to win Bath and Cheltenham? Why couldn’t they have pocketed the scalps of Sir Nicholas Fairbairn and Geoffrey Dickens instead? Why were we shown, at enormous expense, shots from a helicopter of Major’s convoy to the polls? Why did the BBC suppose that anyone would care, or even find it interesting? I found it embarrassingly stupid.

Aftermath. Everyone is stunned. The pollsters are stunned – but their failure will not stop the media and parties using them again at the next election. Labour and Liberal Democrats are stunned at how badly they did. The Tories are stunned at pulling it off. I must confess, for what it’s worth, that I’m stunned myself. In the midst of a recession which is at least partially the fault of the government in power, a government, moreover, which has been in power for three terms, the opposition was unable to dislodge them. If not now, when? Don’t the British believe in two-party government?

At the moment, the talk is of possible moves to Lib-Lab pacts and proportional representation, which could lead to three, four or five-party government. We might then see the Greens again, who managed to gain only 1.3 percent of the vote: they were even beaten by the Liberals pur sang, who gained 1.7 per cent. I’ve not bothered to compute the percentage of the Natural Law Party, in spite of the interest they contributed to the campaign; perhaps if I had managed to acquire a television in time to see them bouncing on pillows I would have felt more minded to do so.

The other party which lost, of course, was the Scottish Nationalists: Scotland was the only part of the United Kingdom which showed a swing to the Conservatives. However, I gather from a friend who has a television that Lord Henderson said in an interview that the Conservatives must do something to assuage Scottish feelings. I don’t suppose that Major will feel too inclined, since he has reappointed Ian Lang as Secretary of State for Scotland.

So now what happens? Almost certainly there will be a Labour leadership contest, and perhaps a restructuring of the Left. All countries have a conservative party of some sort, based on the local equivalent of King and Country; indeed, until the 20th century, the Conservative Party largely contented itself with just that as a philosophy – sometimes garnished with a bit of Burke. It was the Left which was ideological. In this as in so many other areas of public life, Thatcher forced a change, and her period in power saw the culmination of an ideological redefinition of the Conservative Party. Had the new Conservative Party proved unpopular, Labour could have remained as it was, having recently gone through a painful redefinition of its own ideology and policies, with the single goal of returning to power. It didn’t work, and boundary changes will deprive them of a further 15 seats. Perhaps the result of this election which carries the longest-term implications is that, for the Labour Party, doing nothing about relations with the Liberal Democrats seems no longer to be a workable option.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.