We live in interesting times, alas. The new world order isn’t bringing much order to the world. What used to be called ‘actually existing socialism’ is no longer existing in most places, and while capitalism is existing it isn’t doing much better for most people. The warfare state and the welfare state (right or left) are both falling under their own weight, as the economy (market or command) fails to supply their rising demands. Many ‘isms’ are becoming ‘wasms’, and many ‘wasms’ are becoming ‘isms’ again. Old imperialism and Communism are dying, but old nationalism and racialism and older religious fundamentalism and fanaticism are being reborn, and even older despotism and gangsterism are as lively as ever. The Cold War is over, but the hot wars are getting hotter. As the world collapses into what is conventionally called ‘anarchy’, it may be worth taking more serious thought about alternatives to the way we live now, and in particular about what is more correctly called ‘anarchy’. Conveniently, if coincidentally (and indeed curiously), a major Anglo-American publishing conglomerate has produced what is intended to be a new standard book on anarchism. It may not be that, but it was well worth writing and is well worth reading.

The book’s title is a partial quotation of one of the Paris graffiti of 1968 – Soyez réaliste, demandez l’impossible. Equally misleading is the subtitle: this is not so much a diachronic narrative or a synchronic analysis as a mixture of the two – a series of essays and sketches covering some of the people and topics that would be included in such a work. Anyway, a proper history of anarchism could hardly be fitted into a single volume, even one as large as this. When Max Nettlau, the founder of anarchist historiography from the 1880s to the 1930s, turned after many specialist studies to a general account of the subject, he produced seven substantial volumes which got only as far as the First World War. No one has yet overtaken him or indeed caught up with him. Few people have digested all the work done by him, much of which still hasn’t been published, let alone all the work done by his successors. There has been much anarchist activity during the past half-century, there has been much scholarly research during the past quarter-century, and there is still much basic work to be done.

The first task is to get over the stumbling-block of prejudice, and to open one’s mind to other ways of thought and action in political, economic, social and personal life. The second is to study, not the many writings by outsiders about anarchism, most of which are worse than worthless, but the many more writings by anarchists themselves, especially the ephemeral and elusive periodical and pamphlet literature. The third is to put all this mass of material into proper perspective. A single volume which attempts to cover the whole field can offer only a synthesis or a survey of previous research.

For thirty years the standard work of this kind in English has been George Woodcock’s Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (1962), which was a synthesis – an inexpensive paperback, elegantly written, deliberately designed for ordinary readers rather than scholars. There have been other general books, but Woodcock’s has been by far the most successful. Peter Marshall’s Demanding the impossible is a broad survey – an expensive hardback, efficiently written, similarly designed for ordinary readers but with plenty of notes to please scholars. Like Woodcock, Marshall is close to the subject, neither an academic nor an activist but a professional author, rather careless with facts and references, inclusive rather than exclusive, infectiously enthusiastic, attractive to read.

Demanding the impossible is more ambitious than its predecessors in English, simply by being several times bigger and covering proportionally more ground. The Introduction briefly sets the scene, summarising the main features of anarchism and establishing the book as ‘primarily a critical history of anarchist ideas and movements, tracing their origin and development from ancient civilisations to the present day’. The basic definitions are straightforward enough – anarchy as ‘a society without government’; anarchism as ‘the social philosophy which aims at its realisation’; an anarchist as ‘one who rejects all forms of external government and the state and believes that society and individuals would function well without them’; and a libertarian as ‘one who takes liberty to be a supreme value and would like to limit the power of government to a minimum compatible with security’.

Marshall has done a lot of work on a lot of material – though one might wish that he had taken a bit more time and trouble – and has put the results into clear and readable form, so that there is more information about anarchism in this than in any other single volume. It gives a bookish view of the subject, even more than its predecessors do, and it concentrates on intellectuals rather than activists, which is inevitable but unfortunate.

How far is this a book about anarchism, properly so called? Marshall makes clear that there is a long and wide tradition of ‘anarchism’ in the loosest sense – a permanent protest against authority and hierarchy and a persistent demand for both liberty and equality – but he should have made it clearer that most of this tradition belongs not so much to real anarchism – practical argument that a society without government is possible and concrete action to put it into effect – as to what is sometimes called philosophical anarchism – abstract or theoretical speculation or rumination about how nice it would be to have such a society – or to mere libertarianism. Much of the book concerns people who worked long before or well outside the anarchist movement, who may have written or spoken in favour of liberty but who had little or nothing to do with it in the real world. Even some of the so-called ‘Classic Anarchist Thinkers’ have an uncertain status as anarchists – Godwin and Stirner in much of their thought, Proudhon and Bakunin for much of their lives, Tolstoy and Gandhi in much of their activity – and many of the other people gathered by Marshall are fellow-travellers or gate-crashers rather than full members of the anarchist party. Indeed so much space is given to outsiders that relatively little is given to insiders. Thus the formal movement fills less than half the book, and the British movement gets only about 1 per cent of it.

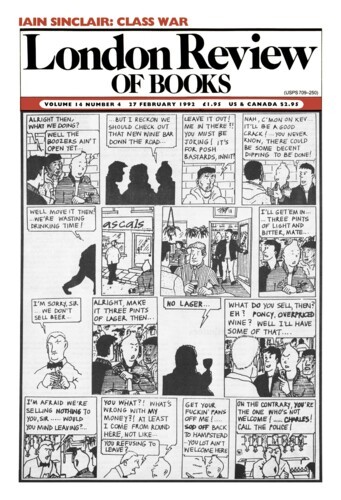

Another question is whether anarchism has any existence as a social fact rather than as an ideal type. Its past importance is clear enough – individual anarchists and the anarchist movement have played an essential if marginal part on the revolutionary stage for a century or two. Its present importance is less clear: is it only a negative critique of capitalism and socialism, or a positive replacement for both of them? And its future importance is quite unclear: what, if anything, does actually existing anarchism say about the situation before us? Consider, for example, two other recent publications. The Self-Build Book is a theoretical and practical guide to designing and building your own home, based on what Colin Ward calls ‘Anarchism in Action’ – peaceful self-help and direct action within existing society. Class War, discussed here by Iain Sinclair, is an anthology of the paper Class War, based on violent confrontation with existing society. They share virtually nothing apart from the word ‘anarchism’ – so are both or either or neither of them anarchist? Marshall prefers the former, though he takes account of the latter, but it is hard to decide whether they belong in the one category, and if so what it is. It may be easier to think of ‘anarchisms’ in the plural rather than ‘anarchism’ in the singular, or even to discard the platonic idea of some thing or things defined as ‘anarchism(s)’ and to adopt a more phenomenological view of some people described as ‘anarchists’.

As in most books on the Left, the macropolitics is clear enough – what anarchists say about public life. The micropolitics is less clear – what anarchists say about private life. And the mesopolitics is quite unclear – how anarchism applies to the rest of life in between. Anarchism is so simple that it can seem simplistic – Engels once sneered that ‘it is so simple that it can be learnt by heart in five minutes’ (Marxism took a little longer) – and anarchist propaganda is always in danger of becoming mere rhetoric. Yet, at its best, anarchism is something much more than a destructive ideology demanding the eradication of authority, hierarchy, competition, exploitation, parliamentary and other forms of representation: it is a creative ideology demanding the establishment of autonomy, autarky, reciprocity, co-operation, mutual aid, and direct action in all human life. What is needed is not a traditional revolution – after two centuries, we may ask, what price revolution now? – but a much more radical transformation in the way we live. When all these questions are answered – not by reading books but by being in the world – it may be possible to decide whether anarchism is just a beautiful dream/dreadful nightmare, or a serious ideology with a future as well as a past.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.