Disemplaning at Baghdad Airport a few years ago, I was met by a guide and interpreter who really did look like a retired torturer. Conducting me smoothly to my hotel (‘Are you a member of the drinking classes? I think the Armenian brandy might tickle your fancy’), he laboured to dispel the image of the unsmiling xenophobic Iraqi which the rest of Baghdad society was at such pains to reinforce. I didn’t know whether to bless or curse my luck when he leaned forward, patted my kneecap and fluted: ‘I believe that we shall be such friends. I have two consuming interests – Adolf Hitler and Oscar Wilde.’ Only hours later, or so it seemed to my disordered fancy, we were sitting in a villa that had once housed the Nazi embassy, while he played a tape of The Importance of Being Earnest. He himself took the part of Algernon, while the role of Lady Bracknell was hogged by a very distinguished British foreign correspondent of what might be called the old school. A large sepia photograph of the Führer frowned from a mantel. Later in the week, we were absorbing a pre-lunch cocktail when my new chum said casually: ‘Would you care to pass the afternoon with Abu Nidal?’

My stock of memory concerning Iraq thus comprises, in no special order, a surreal conversation with Abu Nidal (in the course of which he threatened the life of a Palestinian friend of mine who was later murdered in London); clandestine meetings with Kurds and Communists who whispered about the terrifying cruelty of Saddam Hussein’s police; an afternoon at Babylon; and an amazing number of times in which I was entirely stumped for anything to say. Until the last few weeks I may have been the only person who, if given a word-association test for ‘Hitler’, might well have exclaimed: ‘Iraq!’

So naturally I bristled like a retriever when George Bush began to compare Saddam Hussein with the leader of the Third Reich. Of course, since ‘appeasement’ is the standard metaphor whenever a test of American resolve is in prospect, the figure of Hitler is as difficult to exclude as the head of King Charles. The drawback in the analogy is that, from a Hitler, it is impossible to demand much less than his complete destruction or unconditional surrender. Still, other keywords such as ‘expansion’ and ‘poison gas’ do keep on creeping in. Partly as a result of this, the President has an almost perfect spectrum of political support. Whatever he may decide (and I am writing early in the crisis, without benefit of astrological clergy of the sort who used to cast the White House rune), he will be able to say that even those who did not will the means consented to will the end.

That end, it seems, is either the recuperation of Kuwaiti sovereignty or the removal of Saddam himself – the latter option being known in White House and Pentagon powerspeak as ‘going to the source’. It isn’t being pointed out, and in fact isn’t generally remembered, that the head of Saddam was the very price demanded by the Iranians as a precondition for parley in the last Gulf War. Most Americans are still unsure of how to distinguish between Hussein of Jordan and the Beast of Baghdad (or is it the Butcher of Basra? The Brute of Babylon?) – a distinction which led the New York Times to run a special article on Arabic nomenclature.

In the past, passages of arms between the United States and the Arab world have led to a rash of inflammatory caricature, in which Arabs are depicted either as swarthy unshaven desperadoes or as bloated, oleaginous despots. (The resemblance of this to the classic anti-semitic ‘fork’, in which the Jew is both the Bolshevik and the plutocrat, has been insufficiently remarked.) My impression is that there has been less of this demagogy lately, if only because, on this occasion, the United States is ostensibly mobilising in concert with the Arab world rather than against it. Who would have guessed even a month ago that gallant little Syria would be our ally? Paradoxically, this very inversion has led to unpredictable opposition. It was Congressman Robert Dornan of California, the classic Orange Country patriot and flag-waver, who said this week that ‘American boys don’t die for emirs.’

Those who harbour more general reservations are thrown back on irony. Not only did King Hussein seem like ‘one of ours’ until extremely recently, but so did Saddam. I can attest, as one who bitched about the execution of Farzad Bazoft, that the State Department was unusually reluctant to condemn Iraq. And not just on that occasion either: the gassing of the Kurds and Persians was rewarded with fresh military hardware and even, we now learn, co-operation between the CIA and Iraqi intelligence. Not all of this was dictated by hostility to Iran: American grain-exporters and other businessmen were flocking to Baghdad – which explains the presence of so many ‘hostages’ caught in the country when the situation reversed itself overnight.

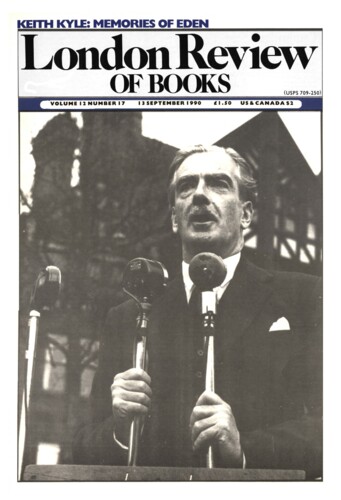

Still, as contrasted with previous adventures and excursions, like the bombing of Libya, the national atmosphere is noticeably free of chauvinism and braggartry. This may be due to the post-Cold War mentality, and it may be the result of the greater seriousness and scale of the undertaking. But there is a good deal of self-criticism in the press, and evidence of a bad conscience about the country’s absurd dependency on cheap oil and on the political arrangements necessary to guarantee it. I think, also, that there is a vague impression that Arab nationalism might have a grudge against the United States. Once or twice a week, some pundit or analyst makes an insecure reference to Suez in 1956. That episode forms almost no part of the collective memory here, but it is dimly understood as an illustration of the law of unintended consequences. The pro-Israeli forces, and thinkers such as Henry Kissinger, have been saying for years that Eisenhower should have sided with the British and French. And Caspar Weinberger once gave an interview to the Washington Post in which he blamed the debacle on the then Labour Government’s refusal to stand and fight. When his interviewer pointed out that it had been the government of Sir Anthony Eden, Weinberger insisted that, no, it had been the spineless Labourites all along. I have forgotten too much of the past to have any hope of repeating it, and think Santayana a windbag, but it still alarms me to see the United States embarking on a military journey without maps.

‘Guilty but Insane’ was Ian Gilmour’s heading for his Spectator review of Michael Foot and Mervyn Jones, whose Suez book Guilty Men 1956 is still one of the best accounts of the collusion. The Spectator has often made trouble for the Tory leadership, with Iain Macleod’s bean-spiller on ‘The Magic Circle’ being the benchmark example until recently. Since Lawson the elder quit the premises, the paper has been through three distinct phases. With Cosgrave and Creighton it was fogeyish while eccentric; much of the time a crank sheet for the Powell crew and the anti-Market, pro-market fringe. However, there was some useful Grocer-baiting as a by-product, and some premonitions of Thatcherism for those who cared to read the auguries. Alexander Chancellor’s regime was much more stylish and eclectic, and took full advantage of the decomposition of the New Statesman (I remember counting no less than 12 former NS regulars in a single Spectator issue in 1983 or so). Chancellor once told me that he had never voted anything except Labour until Thatcher’s third election, and had had quite a sweaty reaction even to this late apostasy.

Fogeyism returned, although without the crankery, with Charles Moore’s young Cantabs. Incredibly unstuffy himself, Moore thought it a good tease to run a kind of Latin Quarter of the Daily Telegraph, where it was often impossible to tell who was and who was not joking. Subjects which mattered, though, were to be found in that odd cluster made up by the Union, the Church of England, the traditional county boundaries and the struggle for a legible and intelligible architecture. People tell me that Christopher Booker is the real intellectual and moral influence upon the Prince of Wales; if so, a version of the Spectator ethos may become semi-regnant in the thinkable future.

Partly because of its historic attitude to Zionism, and partly because of the occasionally breath-taking stuff about Jews written by Taki Theodoracopoulos, the magazine has often had a strenuous time with the Board of Deputies and other manifestations of official Jewry. When Dominic Lawson was gazetted as editor, he received a letter from the Israeli Ambassador expressing the hope that relations with the magazine, which had been ‘tenuous at best’, would now become more cordial. The Ambassador no doubt hoped for better days under a Jewish editor. What he got was a letter saying that the Spectator did not hope for better than ‘tenuous’ relations with any government. My spirits rose when I heard this story.

They have been rising ever since. Whatever the Lawson-Wilson mode may be called, there is nothing fogeyish about it. By way of contrast, the pseudo-chivalrous defences of grand people’s privacy rights – the Queen Mum, the man Ridley, the former Master of the Rolls – have elsewhere touched new peaks of pomposity and special pleading. Listen to Peregrine Worsthorne in the Daily Telegraph of 22 August:

In the old days the relationship between journalist and public man was a bit like that between servant and master. The journalist called the public man Sir and even remained standing in his presence. Inevitably, therefore, the exchange was stilted. Nowadays, with both interviewer and interviewee often belonging to the same club, it is much more like a free and easy exchange between equals.

Worsthorne’s chief artistic usefulness has always been that he can achieve the symmetrical obverse of the truth without being dishonest. In ‘the old days’ the editorialist and columnist, and very likely the reporter too, were inclined to be clubbable with the powerful. Now, with journalism a fast-paced pack activity, deference has become the most noticeable thing about the profession. I was in Aspen, Colorado a few weeks ago, observing the Thatcher-Bush mini-summit on the morning of the Iraqi lunge, and I marvelled yet again at the discipline which those in power can exert over the press. Reporters stand in outright supplicant positions, often for hours, waiting for the chance to ask the most respectful questions. Honorifics like ‘Sir’ and ‘Mr President’ are never omitted. If anyone uses a first name, it is the interviewee bestowing a mark of favour on some network nobody – a gesture always requited by an abject flush of pleasure on the part of the recipient. There’s no need for probing interrogatories in the age of the sound-bite, because what the PM and the President may have chanced to say is by definition the news.

If this were not so, there would not be such a ruckus on each rare occasion when authentic discourse does take place. Alexander Chancellor told me his theory, which was that people such as the Queen Mum, the man Ridley and the former Master of the Rolls do not think of the Spectator as ‘the press’ at all. Like the old gag about ‘members of the press and the gentleman from the Times’, the convention is that a Tory weekly has come to give respectful ear, and that Chatham House rules will be observed. (All right then, I can say ‘wog’ and the fellow won’t be tiresome.) Dominic Lawson has done well to satirise this assumption, for which he was never responsible in the first place. So has A. N. Wilson, who even looks like a beady-eyed, ravenous snooper (high praise intended). For as long it may be allowed to last, may their right hands retain their cunning.

I always think I can tell when someone is joking and when he is not. Lord Denning’s remarks about Leon Brittan (‘Look him up. I think you’ll find he is a German Jew, telling us what to do with our English laws’) don’t strike me as a put-on. Nor was he goaded into making them. In Kingsley Amis’s My Enemy’s Enemy there is a brilliantly-drawn regimental bully, who harries a junior officer in wartime with endless heavy sarcasm – ‘Your pal Musso’ – about his Italianate surname. It’s observed of this character after a bit that if anyone in the mess has any covert sympathy for Mussolini, it is evidently himself. Likewise the Ridleys and Dennings, who use the visceral, uninstructed fear of Germany in order to promote racism and xenophobia. Shurely shome undistributed middle here?

Isn’t it a matter for continual astonishment that bores and bigots of this class go about with the self-pitying impression that their dreary, vicious commonplaces are somehow unsayable; with the notion that it takes courage to mouth off as they do? Denning: ‘In other words, all the words in the language which we used to condemn immorality of any description have been taken out. No bastards, no buggers.’ Oh, I don’t know. A.N. Wilson tells us that he sent Denning the transcript of the interview, so I don’t feel I’m exploiting the senile when I say that Denning is a stupid old bugger and a poisonous old bastard. The difference, as anyone supposedly as interested as himself in free will and morality could tell him, is that children born out of wedlock did not opt to be bastards, and that God or nature supplies us with male homosexuality. He, on the other hand, has chosen to be what he is. The rage of the Tory pundits at the alleged breach of an old man’s confidence – ‘Guilty but getting on a bit’ – is merely the stupid rage of Caliban catching his own face in the glass.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.