A week after Mandela’s release I got a call from Jim Bailey, my former employer on Drum Magazine in Johannesburg where I worked in the late Sixties. He had been elated by the news and set about gathering old Drum hands and sympathisers for a reunion. But by the time we met, he confessed to a sudden weariness, a kind of post partum depression after the forty years of toil and tension.

Bailey is 70. He looks like a creased version of Buffalo Bill with his longish white hair. He wears layers of clothes that seem to have been retrieved from his son’s gym locker and on his head a blue cotton cap against the February cold. He is a Wykehamist, an Ancient History and Classical scholar, who became a Battle of Britain fighter pilot, polo-player for England, and owner-editor of Drum, which started in 1951. He speaks in an incisive Wykehamist style, and has a laugh like the cry of an Egyptian goose. His father was the mining magnate Sir Abe Bailey, a contemporary of Harry Oppenheimers father and a friend of Cecil Rhodes.

Drum was a magazine written by Blacks and ‘Non-Whites’, by what Drum’s finest reporter, Henry Nxumalo, who declared he was fed-up with these negative appellations, asked his readers to settle for: ‘The old contemptibles – Kaffirs, Coolies and Hot’nots. How’s that?’ It flourished under impossible conditions, and made the careers of a group of gifted writers and photographers who might otherwise have had no access to print. There were different editions across Africa – but in South Africa its readers were in the townships. These violent, overcrowded tinderboxes had the highest per capita murder rates in the world, and their occupants had a fierce need to extract whatever pleasures were possible from a situation where survival was an almost impossible obstacle course, an exhausting skill. Drum was a rich mine of copy, and it had the field to itself.

The writers often modelled themselves on Chandler and Runyon, but they had more to write about. They became masters of a deadpan style which exploited the comical, the bizarre and the absurd. There was no shortage of material. You only had to look around and speculate – for example, on a film poster in which Nat King Cole is airbrushed from his seat and the blonde white singer left standing beside the piano without an accompanist. The idea was to entertain, raise spirits, to report on the talent pouring out of the townships, the energy, the razzmatazz, the musicians, the athletes, the boxers, the wide boys, the extraordinary night life. But Drum also did major exposés – of slave labour on farms, of abortion rackets, of the effects of unjust laws.

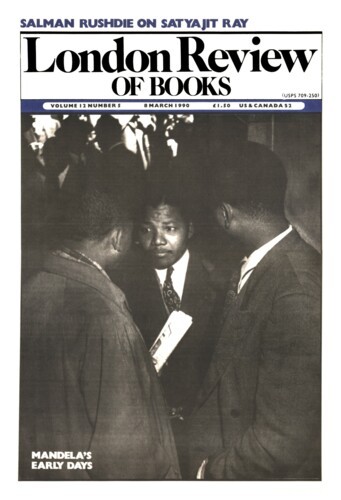

The Fifties had been the great decade, a decade of hope, of Mandela’s Defiance Campaign. By 1967, most of the legendary figures had left, and some were dead: Henry Nxumalo, ‘Mr Drum’, whose portrait hung in the Drum offices like that of an African president, had been murdered while investigating an abortion racket. In exile in New York, in 1965, Nat Nakasa threw himself to his death. The names were spoken with reverence in the Drum office: Lewis Nkosi, Bloke Modisane, Arthur Maimane, and the photographers Bob Gosani and Peter Magubane, Winnie Mandela’s friend, now in New York; Can Themba, whose home in Sophiatown was known as ‘The House of Truth’; Casey Motsisi, who began one column, ‘No nooze is good nooze, but no booze is sad nooze indeed’ – a sentiment warmly shared by most of the staff, who spent much time in jail for drinking or pass offences.

The township people had no place in the South African model; industrialisation had cut them off from their rural origins. Anthony Sampson, who spent a creative four-year stint as editor of Drum in the early Fifties, described as a ‘genuine and massive misunderstanding’ the Afrikaner belief ‘that the blacks, like the Afrikaners, wanted to return to their tribal roots and identity.’ They looked to America, to Harlem and Chicago, for their style – their clothes, their shoes, their music, their heroes. Fortunes were spent on mail order.

Even so, Drum was the only magazine in the world with a columnist who could neither read nor write. She was Aunt Sammy, a toothless, fat and formidably ugly Coloured woman from District Six in Cape Town. Her observations on life were unsentimental and liberating and hard-earned; no censor could have tangled with her copy. She put her political views into action, most memorably in a protest against the Immorality Act when she rode cackling through the streets of Cape Town, naked on a donkey in homage to Lady Godiva, holding a placard which read: ‘Ban the Immorality Act.’ It was a horrible, wonderful sight, and a day of great joy and celebration.

When I arrived at Drum in 1967 there were still some major figures in place. There was Stanley Motjuwadi, a writer of the Fifties generation, and Juby Mayet, who had eight children. They became friends of mine, despite my naivety and starry-eyed zeal. I had many functions – reporter, layout man, occasional photographer. I also had a period as the agony columnist, ‘Dolly Drum’. The column was normally written by Dolly Hassim, ‘advisor to millions’, who was on sabbatical. A typical Dolly exchange ran: ‘I’m 22, in love with a girl of 21, and we are engaged to be married, but soon after our engagement, she fell in love with my brother, who is 33. Please help me Dolly. You are my last hope. Must I kill myself?’ ‘Of course not! It looks as if you have been treated unfairly, my dear, but suicide is unthinkable! If they really love each other, try and forget them. You are still young and can love again.’ I tried to emulate this tone and my formula reply to the universal question was a variation of ‘If you can’t get a straight answer tell him (or her) adios. You’ll soon get over your broken heart.’

Much Drum business was conducted in the shebeens of the townships, or near the office in Eloff Street Extension. In these back rooms, run by shebeen queens – one was called ‘Bitch Never Die’ – we drank vodka, cheap brandy and coke or skokiaan, the township poteen, always warm and sticky and always too much. We returned to the office inspired, full of philosophy, full of advice to the heart-broken millions.

One day after some overtraining in the shebeen, Stanley Motjuwadi and I went off on an impulse to prove the boasts of the Seven Minute Taxi Man. He was offering to take commuters from Soweto to Johannesburg in this time, shaving five minutes off the average. He had one of the huge American cars kept miraculously alive in Soweto – a Chevrolet Straight Eight – and he wanted to be No 1. When the flag went down we understood his strategy. He would drive to Johannesburg on the wrong side of the road. We couldn’t stop him and we crawled like frightened combat soldiers, the worse for drink, into the rear footwell, hoping not to die and hoping not to kill, until our miserable ordeal was over.

But my most demanding and dangerous assignment was investigating the gangsterism in Fordsburg, the coloured township next to Johannesburg. The place was run as a private fief by a man called Sheriff Khan, ‘King of South Africa’s underworld’, ‘swanky knife-thrower and robber with the draw of a Wild West rodeo star’, as Drum had once described him. Everybody was in Sheriff Khan’s pay, including the Police. His speciality was shop-breaking and protection, his henchmen wore tailored suits and he had good lawyers. In my role as Mr Drum, I spent many weekends in this violent place, sitting around in hot backyards, with warm brandy and ‘dash’.

Violence was quite simply a weekend sport. I acquired two protectors, one called Poonie because he was small, the other called Dutch because he looked white and played rugby and spoke Afrikaans by preference. Dutch was the more violent: the terror of the dance halls, he saw himself as Robin Hood. He couldn’t sleep properly on a Saturday night, he told me, unless he’d had what he called ‘a speech’ – meaning a shoot-up, or a knifing. They all carried guns. Grudges went back years. Kick-off was Friday night when cars would scream about, confronting each other headlight to headlight. By Saturday afternoon the hunting and shooting began between the rival cliques and on Sunday afternoon there was a truce, a kind of vespers, when we all gathered outside the gates of Baragwanath Hospital, to, literally, count the dead and assess reputations. My photographs of massacre appeared in Drum and I am somewhat ashamed of them now because, on at least one occasion, I discovered, a beating was set up for my benefit. In retrospect, I took appalling risks. I remember vividly the face of the white policeman, full of hate and fear, sticking his revolver inside our car, squatting in the firing position and screaming that he would shoot to kill. I would simply have been a victim of gangland war in Baragwanath Hospital on a Sunday afternoon.

If I had been much older than 22 I doubt whether I would have had the stamina or the recklessness to take it on. Bailey telephoned me and offered me the job while I was working on the Rand Daily Mail, which was still in its defiant days under its resilient editor, Lawrence Gandar. I had driven down from Nairobi, where I had also worked on a newspaper, and I was full of the glamour of the ‘new Africa’, Lumumba’s and Nkrumah’s and Kenyatta’s. By the time I moved to Drum I had become entangled with the Special Branch. Soon after I had arrived in Johannesburg I rented a house, spacious and remarkably cheap, which, as I discovered only weeks later and through the cuttings of the Rand Daily Mail, had been the home of two prominent members of the Communist Party. The owners were in jail, and their son had committed suicide in the bath that I used every day. The Special Branch didn’t see my tenancy as a coincidence. Mail started disappearing, a camera was stolen, workmen were constantly tinkering.

I moved to a high-rise block in central Johannesburg. A young Afrikaner moved into the adjoining flat, rang my bell and suggested in the doorway that, as neighbours, we could have ‘candlelight dinners’ together. When I refused he jammed his foot in the door. I moved again, this time to a cottage in the countryside outside Johannesburg. There was a two-month delay in getting a telephone, but I needn’t have worried. Two days after I moved in I saw from my bedroom window a line of telegraph poles moving towards my house across the fields from the main road, holes being dug, cable being unravelled. I didn’t deserve such flattery. But it was from that house that one day I set off on a Drum assignment which landed me in the slammer, and caused me the most frightening hours of my life. I went to report on black millionaires who had erected large houses in the townships, on government land. The township happened to be Sharpeville, seven years after the massacre.

It was an innocent assignment, but I had no pass, I had Kenya plates on my car, and a US passport, and I was arrested soon after I got there. I was locked up in a grimy cell with two white men, one of whom immediately turned on me, and kept up his attentions with astonishing energy for many insufferable hours. I remember their names: Bokkie Odendaal, a thick-set, deranged-looking man, old before his time, who was withdrawing from meths, and Danie, a thinner man in white overalls, who until my arrival had been Bokkie’s victim. I only knew Bokkie’s full name because he kept stabbing his finger at his chest and repeating it between his attacks. I made the mistake of asking Bokkie what he was inside for. He screamed at me, picked up a bucket and flung it at me. I thought he was going to try and kill me and went for the bell, but Bokkie assured me it didn’t work. There were smears of blood on the wall. Danie had a black eye and blood on his clothes. He told me that Bokkie had tried to kill him the previous night. He seemed worried for my safety and made a feeble attempt to calm Bokkie down, unleashing further fury. Bokkie would charge at me putting a fist to my face, shouting obscene insults, his face close up, speculating on my, clearly, sexual purposes in the township. It was terrifying. I have never since felt such prolonged and acute anxiety. I remember wishing the real violence would begin: anything was preferable to the fear of it. Bokkie was clearly mad, he had devils in his head and he never rested. When, out of exhaustion, in a lull, I closed my eyes for a second, he would shout ‘Hey!’ and off he’d go again. In fact, he never laid a finger on me, but by the time two Special Branch officers came to see me the following morning, I was in a shaky state. It didn’t dawn on me until later that the intimidation was deliberate and that, mad as he was, Bokkie might never have exceeded his brief. But I was 22. It was enough, however, to sharpen my imagination: what qualities do you need to keep sane under the conditions that applied to the political prisoners in these jails? Is it true that you can get used to anything, submit to anything? It seemed I could barely last two days. The Special Branch mercifully transferred me to another jail and eventually drove me forty miles back to my house, went through every scrap of paper and finally let me go. Outside the magistrates court I met Bokkie again. He was calmer – so calm, in fact, that he had the nerve to ask me for a lift back to Johannesburg.

One day my resident’s permit was rescinded and I was packed off home. Drum survived for another twenty years. It was partly the undercutting of a rival newspaper group, and partly the increasing menace of the violent right wing, that finally persuaded Bailey to sell Drum a couple of years ago. He only sold a husk – keeping the extraordinary photographic archive – and in a nice twist, no doubt much appreciated in the shebeens, he sold it to the Government, who had once tried to buy it secretly in the days of ‘Muldergate’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.