Events are moving fast in East Germany. Over the past couple of weeks, the popular revolution, instead of settling down to a period of quiet preparation for free elections, has been gaining momentum. As many people predicted, the regime of Egon Krenz did not last very long. What toppled him was not, however, the fact that nobody could forget his role in rigging the local elections earlier in the year or his ostentatious endorsement of the Chinese authorities’ massacre of the students in Tiananmen Square. What has fuelled the people’s disaffection with the Communist Party has been the revelation, which apparently came as a shock to almost everyone, of the depth of hypocrisy of the old Honecker regime, with its Swiss bank accounts, its vast hunting preserves and its luxury villas stuffed with Western goodies. The popular anger which has vented itself on the offices of the hated Security Police has been driven by the appalling realisation that the privations and hardships which the ordinary GDR citizen was made to undergo in the name of socialism were not shared by Honecker and his fellow guardians of socialist ideological purity.

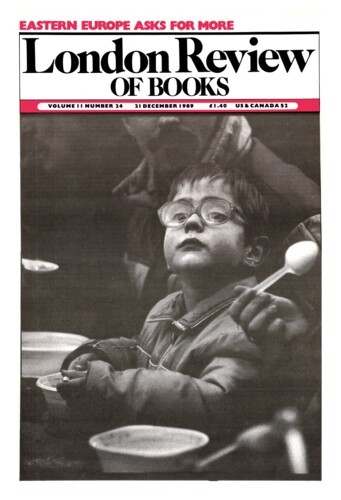

The East Germans have always been considered relatively well off by Comecon standards. Even if many of the economic and statistical claims made by the regime were largely fictitious, still things were never as bad as in Poland or Rumania. Yet material discontents have played a major role in popular dissatisfaction with the regime. When the first waves of East German refugees began to flood over the Bavarian border a few weeks ago, they were welcomed, so the newspaper reports noted, by crowds of West Germans brandishing bananas. It wasn’t an obscure piece of political symbolism: the meaning of the gesture was transparently clear to all concerned. For the fact is that bananas are virtually impossible to obtain in the GDR. And not only bananas. Those millions of East Germans who poured through the Berlin Wall when it was opened early in November did not come back laden with compact-disc players. What they put in their shopping-bags to bring home after their day out in the West was more modest: oranges, mandarins, satsumas, all kinds of ‘southern fruit’ and other foodstuffs which it is virtually impossible to obtain in the GDR.

After a month in Leipzig on an academic exchange two years ago, living off the income provided by the East German authorities – and a very generous income it was too by GDR standards – I came back to the West with an irrational craving for bananas. Staying in a well-furnished new flat provided for me by the Karl Marx University, and cooking for myself, I was able to get meat, potatoes, milk, butter and eggs without difficulty and at absurdly low prices. My daily tram ride to the Deutsche Bücherei, the old German National Library, cost me less than a tenth of what it would have done in West Germany. Beyond the basics, however, choice was minimal.

Even in 1987 it was not difficult to hear the mutterings of discontent on the streets of Leipzig. It was the 750th anniversary of the founding of Berlin, and all the construction workers in Leipzig had been carted off to the capital city to spruce it up for the tourists. Since his accession to power in 1971 Honecker had poured money into new housing schemes, but the older buildings in towns like Leipzig were falling to pieces. The 18th-century centre of Potsdam, where I went later, was virtually in ruins, and most of the plaster work had fallen off the beautiful old Gründerzeit villas on the outskirts. In Leipzig, people were expressing their annoyance by fixing home-made stickers to the rear windows of their cars, mocking the pretensions of Berlin with slogans such as ‘828th anniversary of Leipzig’. There were mutterings too, against the Russians, whose military presence was obvious everywhere.

What people resented above all, however, was the sense of impotence that came with the lack of economic, political and civic freedom. You might be earning enough to buy yourself a little car, but no matter how much money you had, the waiting-list for one of the two-stroke Trabbis which have become familiar from television pictures over the last few weeks was still ten to fifteen years, because the economic plan did not provide for enough to be built to satisfy demand, and foreign-currency problems meant that the planned economy did not allow you to buy foreign, not even a Polski Fiat or a Lada. You might feel like treating yourself to something different from the basic meat and two veg, but unlike West Germans, East Germans who live outside the capital are starved of choice. I did manage to find a Vietnamese restaurant in Leipzig, but was told there was a six-month waiting-list for a place. Meanwhile everyone spent their evenings watching West German television, which not only indulges in orgies of consumerism during the advertising breaks, but also carries numerous programmes about places like France, Italy and Spain, to which the citizens of the GDR were unable to go. Moreover, West German TV carried frequent news and current-affairs programmes which gave a very different picture of Eastern Europe from the one available on the GDR’s own TV stations. So much so, that East Germans habitually referred to an area around Dresden prevented from receiving Western TV by a range of intervening hills as ‘the valley of the unenlightened’.

What drove increasing numbers of young East Germans to leave for the West even before the current wave of emigration – and Honecker, in his last years, was far from averse to letting them go, fearing the consequences if they stayed behind to foment discontent – was a sense of despair, a conviction that nothing would ever change. And indeed, the material conditions of life which I encountered during my visit in 1987 were little different from those I had met on my first visit, in 1971. More cars and more new houses, perhaps, and more electrified railway lines, but also more pollution and more urban decay. The desire for change has sprung from the consciousness that the old regime offered nothing to look forward to, nothing to aim for in life. Everything necessary for daily existence was secure: free schooling, medical care, crèches and kindergartens, cheap basic foodstuffs, subsidised housing and inexpensive public transport. What it did not offer was hope of a better life in the future.

The chances of political change under the old system were indeed small. The non-Communist parties in the GDR have been completely under the thumb of the ruling party for decades, and officially recognise its leadership; their programmes scarcely differ from that of the Communists, and their function has been mainly to serve as ‘transmission belts’ for Communist policy and ideology to reach sections of the population such as the Christian Church which are unwilling to commit themselves explicitly to Communism. So thorough has been their subordination that it is doubtful whether their inclusion in Hans Modrow’s new government really has much much more than symbolic value. The satellite parties are distancing themselves rapidly from the old regime. But they have some way to go before they win any real credibility.

Ironically, as so often before in the history of East Germany, the Russians have been the catalyst of political events. It was above all President Gorbachev’s pointed refusal to support Honecker’s hard line during his visit to East Berlin on the 40th anniversary of the Republic’s foundation that persuaded the people that popular demonstrations for change would not have the Russian tanks rolling out onto the streets as they did in 1953. What they have achieved may well be far more than Gorbachev bargained for. But there is clearly no going back now. The East German people have made it clear that they will not be satisfied until they have gained freedom to travel, freedom of economic choice, and freedom of opinion, which includes free elections.

Is this all they want? What about reunification? What about the importation of Western institutions? After the initial euphoria, the realisation seems slowly to be dawning on Western politicians and journalists that perhaps, after all, the aspirations of the East Germans are not – so far, at least – running in this direction. Of those questioned, in what one might term an ‘exit poll’, as they came through the Wall for their first visit to West Berlin on that memorable weekend, some 70 per cent said they were not interested in reunification; only 28 per cent said they were. Another poll has produced an 83 per cent majority against relinquishing national sovereignty. There have been banners and slogans demanding reunification at the Monday demonstrations: but so far they seem to represent the views of a minority, though one that has been growing over the weeks. Neues Forum and the other opposition groups are adamant that they are seeking reforms in their own country, not merger with another one. Almost every time any East German citizen has been interviewed in the press, the language spoken has been that of ‘reforms in our country’, ‘our republic’.

Moreover, nearly all the opposition groups in the East, including the Christian ones, seem to think of themselves in some sense or other as socialist. Even West German politicians are warning that refugees from the GDR – that is to say, those who are most actively committed to a market economy – will find it difficult to adjust to the pushy, ‘elbow society’ of the Federal Republic. There seems to be a wide measure of consensus among all political groups in the GDR that what is on the agenda is a renewal of socialism, not the importation of Western-style capitalism. And there are very good historical reasons for this. Before the Wall was built, over two and a half million East Germans left for the West and it is a fair bet that they included the overwhelming majority of those social and political groups who were strongly committed to Western-style liberal and conservative politics and to a free market economy. Dissidence in East Germany since then, in contrast, say, to the Soviet Union, has been almost exclusively socialist dissidence. Forty years of socialist education and propaganda have inevitably left their mark on the young. And, as an overwhelmingly Protestant country, East Germany lacks a great reservoir of conservative Catholicism of the kind that can be found in Bavaria. A Catholic peasantry like the one in Poland does not really exist in the GDR, where farming, traditionally done on a large scale, has been collectivised since the Sixties.

The East German population has so far shown a degree of identification with its own country which might seem surprising. Here we might turn for enlightenment to the example of Austria, which was part of Germany until 1866, under the Holy Roman Empire and its successor the German Confederation. With the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy in 1918, the inhabitants of what was now known as German-Austria were virtually unanimous in wanting their country’s absorption into the fledgling Weimar Republic. The merger was prevented by the Western Allies, who could not accept that the Germans should come out of the war with their territory enlarged. It was an Austrian statesman, Ignaz Seipel, who then coined the phrase ‘one nation, two states’ which has been applied more recently to the GDR and the FRG. When the Nazis came to power many Austrians started to have second thoughts about a merger with Germany, yet the Anschluss of 1938, which resurrected the ‘greater German’ idea of unification ditched by Bismarck in 1866, was still in all probability welcomed by a majority. It was only after the harsh experience of Nazi rule, and above all after 1945, when the Austrians, for all their heavy involvement in Nazism, were offered a fresh start, that ‘German reunification’ ceased to mean a union including Austria.

The real question facing Europe now is how far the East Germans have succeeded in developing a consciousness of their own statehood along Austrian lines. For the idea of a common nationality does not necessarily imply an acceptance of a common state. Since 1974, it is true, the East German Constitution no longer describes the GDR as ‘a socialist state of the German nation’, but identity documents still leave one space to be filled out for ‘citizenship’ (GDR) and a separate one for ‘nationality’. The evidence seems to suggest that the East Germans have travelled some way down the Austrian road, but certainly not as far as the Austrians have. Honecker’s attempt to build a sense of GDR patriotism through international sporting achievements and identification with historical figures like Martin Luther has fallen short of its goal. If the new regime in the GDR fails to improve standards of living within the next few years, a majority may well lose what commitment they have to a separate existence for their country.

The dramatic events in the GDR have led to issues of national identity and pride, previously some way down the list of priorities in the minds of most West German voters, assuming a new importance in West German politics. Yet talk of a ‘Fourth Reich’ is historically ignorant and politically misguided. True, there are those, such as the Republicans in West Germany, who want a neutralised Germany equipped with a full nuclear arsenal, hanker after the ‘lost’ territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, and look back with nostalgia to the days of Nazi rule. Opinion polls suggest that the potential for right-wing extremism among the West German population is now 10 to 15 per cent. And Chancellor Kohl is sufficiently avid for the votes of these people to pander to their views by refusing to endorse the permanence of the present Polish-East German border.

On the other hand, with the flight and expulsion of eleven million Germans from Eastern Europe after 1945, and the swelling tide of emigration to the West among ethnic Germans in the last couple of years, one of the major incentives to pan-German nationalism of the sort that lay behind Hitler’s ambition to unite all Germans in a single Reich has more or less disappeared. The social and political forces that gave rise to Nazism and pan-German nationalism in the past are now weak. The old Prussian aristocracy has lost most of its land, its influence and its status. Big business has become Americanised. The Army has been incorporated into Nato. The urban artisanate has shrunk into insignificance, and the peasantry – also much fewer in number now than in the days when millions of farmers and farm labourers voted for the Nazis – spends its time milking the European Community for subsidies. The experience of two world wars left the middle classes with an understandable longing for peace and stability. While Weimar democracy was associated with economic and political failure, the forty years since 1949 have given West Germans the confidence that democracy can deliver prosperity and order.

Reunification in any case would be unlikely to take the form recently suggested by Sir Leon Brittan – that is, a simple extension of West German institutions to the East. Given their apparent commitment to some form of socialism, the citizens of the GDR would probably want to retain a substantial degree of autonomy. Even if the first stages of Chancellor Kohl’s ten-point plan for unity were acceptable, there must be a great deal of doubt about the rest. In trouble domestically, Kohl is playing the nationalist card in preparation for the next election. Whether his plan is realistic remains to be seen. For all his reunification rhetoric, he might want to think twice before adding to the West German electorate several million East Germans the great majority of whom would probably vote for the Social Democrats. The last word in any case would have to lie with the United States and the Soviet Union, and here too – particularly in Moscow – there is evidently a great deal of reluctance to entertain a simple merger of the two Germanies. If reunification ever happens, it is likely to be on the basis of some form of loose confederation within the European Community. This has many parallels in German history, from the Holy Roman Empire to the present-day Federal Republic – though the federal system would probably have to be loosened up a good deal to accommodate an East German Land or Länder. The resulting state would most probably be a good deal weaker than some commentators fear. It would not be the first time that Germany appeared on the international stage as an economic giant but a political pygmy: but such a discrepancy might well arouse less resentment in Germany at the beginning of the 21st century than it did at the outset of the 20th.

Meanwhile, a note of caution is beginning to replace the initial euphoria. West Germans seem divided on what to do next, with Chancellor Kohl’s Christian Democrats calling for reunification and the opposition Social Democrats generally remaining more sceptical. On the borders, the West Germans have stopped handing bananas to incoming visitors from the East and are handing out condoms instead. Perhaps this indicates a feeling that the barriers are being coming down too quickly: Aids is a major worry in the Federal Republic, while public education about HIV infection in the East has been minimal. The influx of East Germans in search of jobs has begun to arouse hostile comment in some quarters of West German politics, and the economic aid now promised by the Kohl Government for the beleaguered East is designed not least to persuade the GDR’s inhabitants to stay where they are. In East Berlin, meanwhile, luxury-goods shops are being cleaned out by West Germans armed with hard currency, and in some respects the opening of the Wall has only increased the economic problems faced by the GDR.

Two years ago, the overwhelming impression the visitor gained of ordinary people in the East was one of grumbling acquiescence. The suddenness of recent events has taken everyone by surprise. We are all having to do a lot of rethinking. In a curious way, the present revolution also marks the revenge of the long-neglected provinces against the dominance of East Berlin. It’s what is happening on the streets of Leipzig, not Berlin, that is setting the pace of events, and the most trusted politicians, such as Hans Modrow, come from Dresden rather than the capital city. After many years of subordination, the Saxons seem to be reasserting themselves once more and pushing the Prussians out of the limelight.

Writing before the special Communist Party Congress has opened, it is difficult to know what will happen next. But if I don’t succeed in finding any bananas in the shops, the next time I go to the GDR, I’ll know that the East German reforms have a long way to go.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.