Considering that they have rejoiced so often in wrapping themselves in the Union Jack, Tory governments have an inglorious record on defence. Churchill’s notorious entry in the index to The Gathering Storm (‘Baldwin, Stanley ... confesses putting party before country’) may not have survived as an objective historical judgment, but even fifty years on, Britain’s preparations for the Second World War hardly look inspiring. The next long spell of Tory government in the Fifties saw Britain’s conventional forces run down without revealing how her nuclear capability, which was supposed to justify this, could be made plausible. It was Macmillan’s lot to discover that, when he could no longer rely on British technology, the American weapons on which the ‘independent’ deterrent had become dependent were equally liable to end up on the junk heap. The Thatcher Government proved incompetent to defend even the Falkland Islands, though its gambler’s throw in belated overcompensation for its negligence hit the political jackpot on the rebound. And yet Tory prime ministers from Balfour to Home have found an excuse for clinging to office in the contention that the defence of the homeland simply could not be entrusted to their political opponents.

There is reason to suppose that the efficiency and economy of Britain’s Armed Forces may have benefited more than once from the intelligent stewardship of ministers who managed to surmount the crushing disability of not belonging to the patriotic party. When Haldane was sent to the War Office under the last Liberal government, the piquancy of the situation was not lost on him. ‘The General is in uniform and booted and spurred,’ he wrote of an early encounter, ‘but the Secretary of State is in a tweed suit with a soft hat.’ One of the most patently cerebral members of the Cabinet, Haldane was prepared to turn a powerful and well-schooled philosophical mind to the unresolved dilemmas and incoherence of British strategy. The Prime Minister’s comment, ‘We shall now see how Schopenhauer gets on in the kailyard,’ employed an idiom with which the Army Council was soon to become familiar. When they asked Haldane what sort of an army he had in mind, his reply was: A Hegelian army.’

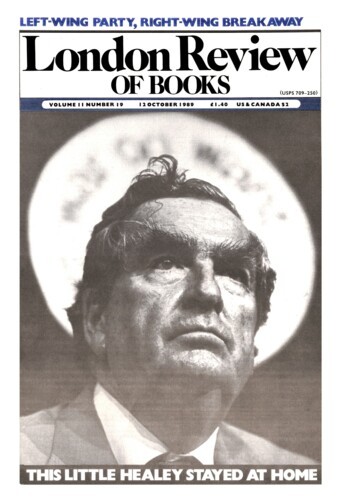

Denis Healey calls his six years at the Ministry of Defence in the Sixties ‘the most exhilarating period of my life’ and ‘the most rewarding of my political career’. These are, of course, relative judgments, reflecting the barrenness of Labour politics in the subsequent years. But his achievement in rethinking Britain’s strategic role-matching the means to the ends and defining ends that were within her means – entitles him to comparison with Haldane. They are comparable, too, as intellectuals in politics who reached out to books as part of their political resources. One of the engaging features of Healey’s memoirs is the explicit but unpretentious way that he brings this out. Explaining his position as ‘an eclectic pragmatist’ when he became Chancellor of the Exchequer, he comments: ‘Karl Popper played a far more important role in my thinking than Karl Marx-or Maynard Keynes, or Milton Friedman.’ Perhaps he was wise, however, not to have declared a Popperian policy as his objective.

As Defence Secretary, Healey found the work ‘all-consuming’. In proving himself a highly capable departmental minister, he became somewhat insulated from the mainstream of politics. Perhaps, indeed, his detachment from the immediate pressures and conflicts of the Labour Party helps explain his unique interlude of positive job-satisfaction. He justly rebuts the charge that he was simply a ‘technocrat’. Though deeply affected by his own wartime experiences, notably as a beach-master at Anzio, Healey did not lose sight of his essentially civilian role in making the defence establishment accountable. With his soft hat on his hard head, moreover, he was intellectually capable of responding to the challenges posed by defence strategies in the context of a shifting balance of power and a rapidly evolving nuclear technology. If he was a reluctant convert of the abandonment of Britain’s posture East of Suez, nonetheless the decision to withdraw, once taken, was implemented expeditiously so as to save money where Britain could no longer save face. He looked beyond the ‘illusions of grandeur about our post-imperial role in Asia and Africa’ which he discerned in Wilson. As Healey writes of the withdrawal from Aden: ‘All alternatives would have been worse.’

Over the British nuclear deterrent, Healey’s approach can be termed either brutally pragmatic or woefully disingenuous: either way, it did him no good in the long run. Labour had no commitment to continuing the Polaris programme – rather the reverse – and Healey discovered in 1964 that the two hulls already laid down could have been converted into hunter-killer submarines at no extra cost. This news, however, was withheld from the Cabinet. ‘Wilson wanted to justify continuing the Polaris programme on the grounds that it was “past the point of no return”. I did not demur.’ In a period of leapfrogging technological rivalry between the superpowers, however, the recurrent problem was still that of staving off British nuclear obsolescence by trying to cadge American weapons on the cheap. ‘At one stage in our discussions,’ Healey reveals, ‘Harold Wilson got so discouraged that he suggested selling our Polaris submarines back to the United States.’ Instead, in the Seventies, Polaris was eventually updated with Chevaline – a commitment inherited from the Heath Government which Healey now regrets not having scuppered when he became Chancellor in 1974. More than anyone else, he was responsible, by commission and omission, for the maintenance of ‘a British bomb’. And it was this which became the dominant emotive symbol in the subsequent political controversy over defence, which might more pertinently have been focused on the clear issue of British membership of Nato. If Healey’s career was ultimately stalled by the rise of unilateralism in the Labour Party, he can truly be said to have been hoist with his own petard.

It is one of the appealing features of Healey’s memoirs that he still manifests the intellectual energy to engage in serious appraisal of political arguments at every level from abstract theoretical propositions to concrete political instances. He is candid and self-revealing in a manner free from rancour and petty self-exoneration. This does not, of course, mean that he is humble or reticent about his own role, but there is a robust integrity to his account which makes it simultaneously worth learning from and worth arguing with. He is right to think that his political career spans a period of unusual interest – ‘My generation has seen it all’ – and even the evasions can tell us a good deal.

During the last twenty-five years, Britain’s ruling class has become identified as an upwardly mobile Oxbridge meritocracy recruited through provincial grammar schools. When Denis Healey encountered Edward Heath and Roy Jenkins at Balliol just before the Second World War, such was their tryst with destiny. This was in Healey’s Communist phase, which lasted until the fall of France. When the Marxist-dominated Labour Club split in 1940, he opposed Jenkins and Tony Crosland – ‘more from inertia and indifference than conviction’ – in their move to set up a rival Democratic Socialist Party. It was thus the war which made Healey into a social democrat, instilling the political lesson of planning and an emotional charge of comradeship which he recognises as the peculiar product of the era. ‘Thatcherism became possible only when the wartime generation was passing from the stage.’

After the heat of battle, the Cold War provided the further crucial stimulus in the making of his political identity. As international secretary at the Labour Party Headquarters, Healey articulated the rationale of Bevin’s foreign policy, justifying the turn against Russia in terms of a Soviet expansionary thrust (about which he now believes himself to have been mistaken). Healey, then, was unambiguously a figure on Labour’s right wing, and, as a young MP for a Leeds constituency in the Fifties, he was naturally drawn into Hugh Gaitskell’s circle. The tone adopted towards Gaitskell, however, is pretty cool in these memoirs, which record doubts about ‘whether the fierce puritanism of his intellectual convictions would have enabled him to run a Labour government for so long, without imposing intolerable strains on so anarchic a Labour movement’. Healey rightly affirms that Gaitskell was not, in Bevan’s phrase, ‘a dessicated calculating machine’ (though he falls into the common error of identifying Gaitskell as the butt of an epithet which Bevan in fact intended for Attlee).

After Gaitskell’s death in 1963 (persistently misdated here), the Labour Party was temporarily invigorated and permanently demoralised by another style of leadership altogether. Healey’s view of Wilson as prime minister is not flattering: he lacked political principle and sense of direction, yawing between ‘a capacity for self-delusion which made Walter Mitty appear unimaginative’ and a paranoid propensity which discerned conspiracy on every side. Yet Wilson’s personal attributes are not represented as fundamentally disabling in a man who went on to lead the Party for another ten years. Indeed the same characteristics are seen as functional in the context of Labour’s fissiparous inconsistency over the Common Market in 1971. Healey commends Wilson’s ‘great courage’ at this juncture in seeing that the leader’s ‘overriding duty’ was to secure party unity, ‘fully aware of the ignoble role’ which was demanded of him. Hence Wilson’s feeling remark: ‘I’ve been wading in shit for three months to allow others to indulge their consciences.’ This, it seems, is the final measure of what the Labour Party owes to Harold Wilson – the Ordure of Merit.

There is more than one view that can be taken about the Labour Party in this period, each with some verisimilitude. One is to accept its historic role as a class party, represented through the Trade Unions: to acknowledge its vested interests but to maintain that they are the right vested interests. If this is hard-nosed and mechanistic, another view is soft-hearted and romantic: to glory in the Party’s peculiar, populist, radical heritage, albeit one so often corrupted by the machinations of the leadership. A further position is more critical: to identify the developing structural weaknesses of a party ostensibly devoted to the cause of the disadvantaged but, in the literal sense, constitutionally incapable of resisting the entrenched sectionalism of the Unions. Healey’s outlook is compounded from aspects of all these views, as befits an ‘eclectic pragmatist’. Social democrats of his generation have certainly been faced with the painful necessity for some rethinking. How, then, does his synthesis add up? Does it adequately explain his own difficulties in the Labour Party in recent years – or justify his choice of strategy?

Healey is a cosmopolitan figure – well-travelled and multilingual – who can perfectly well see that ‘the Continental parties have adjusted much better to social and political change than the Labour Party,’ which remains ‘the most conservative party in the world’. Its constitution ‘must be the weirdest in the world’, vesting the block vote in the hands of a small number of power-brokers. Hence the Labour Party’s inability to adapt to the sort of social changes which it had helped to promote. ‘The trade unions were now emerging,’ Healey comments from the perspective of 1970, ‘as an obstacle both to the election of a Labour government and to its success once it was in power.’

These difficulties intensified during the Seventies, especially during the period of Labour government from 1974 to 1979 when Healey was Chancellor of the Exchequer. He offers a rueful defence of his record, faced with pressing external difficulties for which the conventional Treasury policies offered an inadequate remedy. Showing understandable irritation with self-styled Keynesians (‘who had usually read no more of Keynes than most Marxists had read of Marx’), he makes no bones about saying: ‘I abandoned Keynesianism in 1975.’ To call him a convert to ‘the monetarist mumbo-jumbo’, however, is merely a polemical taunt, though one he laid himself open to by publishing the Treasury’s monetary targets, albeit in a spirit of weary cynicism. In fact, his strategy was to obviate the necessity for the restrictionist measures of monetarism by relying on the Trade Unions to fulfil their side of a bargain with their own government. ‘They did not,’ Healey concludes; and although he is prepared to acknowledge ‘hubris’ in aiming at an anti-inflationary norm that proved too ambitious, he is forthright in apportioning the real blame for the Winter of Discontent and Labour’s subsequent loss of power. ‘The shambles was of course a triumph for Mrs Thatcher,’ he maintains. ‘The cowardice and irresponsibility of some union leaders in abdicating responsibility at this time guaranteed her election; it left them with no grounds for complaining about her subsequent actions against them.’

Healey explains that ‘the Labour Party’s financial and constitutional links with the unions made it difficult for us to draw too much attention to their role in our defeat.’ He calls Callaghan ‘the best of Britain’s post-war prime ministers after Attlee’, but points out that he ‘belonged to the generation of Labour leaders which had come to depend on the trade-union block vote for protection against extremism in the constituencies’. Callaghan may have made this his stock-in trade: but his position was one implicitly adopted by many old Gaitskellites who were more chary of admitting it. Behind a paper-thin screen of social-democracy theorising, Gaitskell’s leadership had relied on the block votes of the right-wing unions in the context of the Cold War. As these conditions passed, the hollowness of the social democrats’ position was progressively exposed. When a number of them left the Labour Party to found the SDP in 1981, the taunt was that they were machine politicians whose machine had broken down. Was the main difference between them and Healey that he obstinately refused to acknowledge that the machine had broken down?

‘I was not surprised by the consequences of that unhappy experiment,’ he briskly concluded: ‘right-wing breakaways from left-wing parties have never come to anything.’ This confident proposition, of course, imports undeclared postulates about the meaning of left and right, and their unchanging relevance to a static class structure and a given role for trade unions – postulates which, in other compartments of Healey’s eclectic mind, have long since been discarded. Did he really not appreciate the potential fragility of the two-party system in 1981-2? He writes himself of Benn that ‘when he came close to capturing the Party machine, he came close to destroying the Labour Party as a force in 20th-century politics.’ If Benn had been elected deputy leader in 1981 instead of himself, Healey asserts, ‘I do not believe the Labour Party could have recovered.’ And since the outcome of that contest was so unpredictably close – decided by a decimal place of nothing in particular – the survival of the ancien régime in British politics must surely have been less than predestined. Moreover, far from lending comfort to the Tories, the Alliance was at this stage rightly seen by them as the only effective threat to their position. Actually, as Healey admits, it was the Falklands which restored the fortunes of the Thatcher Government, causing ‘a collapse in support for the Alliance, which never recovered’. The fluidity of these events during a critical period of little more than a year is thus nicely caught by Healey when he turns his mind to remembering how it really seemed at the time – only to be ignored in his self-serving conclusion: ‘The lamentable history of the SDP bore out all the warnings I had given.’

The fact is that Healey was unprepared to draw radical inferences from his own analysis of the Labour Party, because he remained rooted in so many of its conventional assumptions. No doubt there were personal as well as intellectual reasons. Why should we doubt him when he says, at another point, that ‘any thought of leaving was ruled out by my sense of loyalty to my friends in Leeds’? Temperamentally, too, the ‘inertia and indifference’ which had stopped him throwing in his lot with Jenkins in student politics in 1940 now came into play on a bigger stage. Healey had so many reasons to stay in the Labour Party that the issue is truly overdetermined. He still hoped against hope that, if only he kept his head down, a bit of opportunistic tinkering with the old machine could stick things together again. Hence his circumspect refusal to take a stand against the constitutional proposals put forward in 1980 – ‘the fight I was being asked to lead would have had no prospect of victory’ – and his continual calculation on the likelihood of this or that union delegation delivering its block vote, by hook failing crook, by accident failing design. These tactics were not only inglorious but unsuccessful; they left him roundly defeated for the leadership but narrowly elected as Michael Foot’s deputy by the end of 1981.

‘I felt myself compelled to agree with Michael in public on all issues at all times,’ Healey admits. It was hardly a happy position; and a less robust and pragmatic man might have found it unbearable. On the defence issue, which came back to haunt him, Healey was not, of course, convinced by any of the versions of official Labour Party policy which emerged in these years, but contented himself during the General Election of 1983, with a ‘feeble statement of my real views’ on a radio phone-in programme. He can make the point that Labour did not nail itself to an explicitly unilateralist policy until after the 1983 Election: but on his role in fighting the 1987 Election on a defence policy to which he was, therefore, unambiguously opposed, he is discreetly silent. The old Gaitskellite had evidently resolved not to fight and not to fight and not to fight again to save the party he loved.

Healey quotes the philosopher Lesjek Kolakowski’s definition of social democratic politics as ‘an obstinate will to erode by inches the conditions which produce avoidable suffering, oppression, hunger, wars, racial and national hatred, insatiable greed and vindictive envy.’ He acknowledges two political heroes: Ernest Bevin and Franklin Roosevelt, citing their ‘powerful sense of direction which was rooted in moral principle, and streetwise pragmatism in choosing the best route forward’. Healey writes percipiently at several points of the contradiction of politics, of politics as a necessary but flawed process, in which moral uprightness is not a sufficient guarantee of constructive achievements. Stating these precepts, of course, is one thing and applying them is another. Politics, he concludes, means accepting the ‘constraints and disciplines’ of party, and entails ‘acquiescing in policies you dislike until you can persuade your party to change them. It will often bring defeat – and sometimes personal humiliation.’ This begins to sound like his own bid for the Ordure of Merit.

Was it all worth it? The state of the Labour Party today is one pragmatic test. It is now beginning to look like an eligible alternative to Thatcherism, having accepted a range of policies which, back in 1981, would have been unthinkable. They would, at any rate, have been unthinkable for Labour, though their thrust is actually not so different from what the SDP originally stood for, however embarrassing this may now seem on both sides. The crucial piece of unfulfilled business, as Healey recognises, is to wrest control of the Labour Party itself from the Trade Unions, which in the nature of things can only be done with their consent, willingly or unwillingly given. Even if it is true that Labour has belatedly adopted through bitter experience much the same posture which the SDP adopted eight years ago through intelligence and foresight, no one has good reason to gloat – except Mrs Thatcher. At any rate, if Denis Healey were to be asked what sort of social democratic party he had in mind, there is surely no doubt what he should reply: ‘A Kolakowskian party.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.