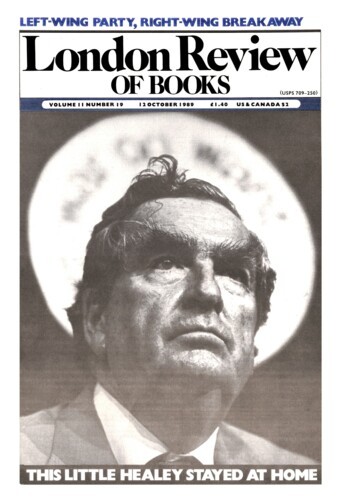

One of the ways politics has changed over the last three decades is illustrated by the fact that in 1956 there were only two Jews in the Conservative Parliamentary Party, both of them baronets – and one of them had been elected in a by-election in February of that year. He was Sir Keith Joseph, son of a Lord Mayor of London and director of the family construction firm of Bovis. It was the year of Suez and in a very gentle way he was a rebel. He did not think that Nasser should be destroyed because he might be replaced by someone worse, and he felt that any British action should be under the auspices of the United Nations. As a consequence of these views becoming known, he was taken out to lunch by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. ‘That,’ as his new biographer Morrison Halcrow puts it, ‘more or less ended his excursion into foreign affairs.’ He was, however, given one small but important duty, not mentioned in this book. He was sent round to the offices of the Jewish Observer and Middle East Review to try to persuade its editor, Jon Kimche, not to persist with the story, which he alone was publishing, of MI6’s ‘black radio’ stations which were blackguarding Nasser in Arabic as a closet pro-Zionist. But Sir Keith had less luck with the editor than the Earl of Selkirk had had with Sir Keith.

When Sir Keith came out of the Army at the end of the war, already a baronet and a man of considerable wealth, he set himself to round off three pieces of unfinished educational business within a year. He earned his licentiate of the Institute of Builders, he was called to the Bar, and he was elected to a fellowship of All Souls. He felt pressed for time and had a good mind – the concentrated effort can be applauded. But why, one might ask, was it necessary for him to starve himself the while to the point of giving himself a severe stomach ulcer which lasted for the next ten years? It is in matters such as these that the limitations of this interesting, sympathetic but not uncritical biography make themselves felt. Its subject, who was co-operation itself over public affairs and so self-critical as to be almost embarrassingly dismissive, clammed up over anything remotely to be described as ‘home life’, and the author’s other sources do not seem to have been of much use. Halcrow offers no explanation of this early instance of self – mortification other than to note that a Jewish friend said of it: ‘That’s very Jewish.’ All one learns of Joseph’s marriage, which took place in 1951, is that his bride was an American and photogenic and that in 1978 a single-sentence statement recorded in the press that they had ‘decided to live separately’.

Although he became chairman of Bovis for a short while, Halcrow implies that Joseph was a bit out of place as an industrialist; he failed to practise at the Bar; and as a Fellow of All Souls he found himself unable to finish a thesis about tolerance and how to differentiate between it and indifference. There was really nothing for it, given his conscientious attitude to life, but to go in for a career in politics in many ways, as he saw it, an extension of his considerable lifelong interest in charities, mainly those concerned with the elderly but also the Howard League for Penal Reform. In the Commons, on issues of conscience he voted ‘liberal’, against hanging and for the reform of the law on homosexuality. He was known to set a high value on intellectual honesty. To Halcrow, a Parliamentary correspondent in the Sixties, he ‘seemed to relish bad news, not least about himself’.

His rise was fast – PPS after one year, junior minister after two more, the Cabinet less than three years after that. He was regarded at the time as one of the Tory Party’s brightest hopes for the future. When he and Sir Edward Boyle were brought into the Cabinet by Macmillan on ‘the Night of the Long Knives’, it was with a flourish – the old showman’s theatrical salute to youth and brains. Joseph, as Minister of Housing and Local Government with a background in the construction industry, became the booster of the high-rise block and the onward march of the New Technology. He was for everything that the Prince of Wales is against. Looking back ruefully on his record from a perspective of thirty years, Lord Joseph now tells his biographer: ‘I was a “more” man. I used to go to bed at night counting the number of houses I’d destroyed and the number of planning approvals that had been given ... Just “more”.’

When the leadership of the Conservative Party became vacant in 1965 Sir Keith was a Heath man: he lobbied for him and recruited Margaret Thatcher to that camp. Heath, to all appearances, was to bring into being a new radical form of Conservatism, which was known in the run-up to the 1970 Election as the politics of ‘Selsdon Man’, after the hotel where the strategists drew up the programme; it is now familiarly known as Thatcherism. Of this creed Joseph was the high priest (or chief anthropologist). He organised countless study groups, striving after his own high standards of intellectual rigour. He began to acquire a harrowed look, the sweat poured out from under his close-cropped curly hair, the vein on his forehead vibrated alarmingly. On television he found great difficulty in giving a short answer to any question, not because he wanted to be evasive but because he saw too many sides to it. Most particularly, he needed to be able to show how his belief in market economics could be made to ride with a caring society.

As Secretary of State for the Social Services in the Heath Administration, Joseph was very largely spared the need for such painful choices; he was known as the last of the big spenders, though Margaret Thatcher at Education ran him pretty close. Seeing himself as strong on government management, he installed the three-tiered structure for the National Health Service that every reformer has since been trying to get rid of. He took a strong stand on including contraception as a normal part of the Health Service, though not everyone would have used as an argument for this liberal view the notion that ‘some women don’t have a flair for maternity at all, and if they haven’t a flair, and aren’t going to take trouble either, why bring a child into the world at all?’ This artless venture into eugenics passed almost unnoticed at a time when those who might have been expected to react were pleased with the overall effect of his decision. It was not the only time he was to say it and next time he was not to be so lucky.

When next he found himself out of office, in the traumatic circumstances of 1973-4, Joseph, having been a Tory all his life, was, by his own account, ‘converted to Conservatism’, by which he meant that ‘Selsdon Man’ must set the tone for everything the Party did and said, and in a much more thoroughgoing way than had hitherto been contemplated. There should be a complete rejection of corporatism, Keynesianism, consensualism, everything that the Earl of Stockton meant by ‘the family silver’; monetary policy and supply-side economics should prevail. While Margaret Thatcher has given a picture of Joseph as both her teacher and her doughty champion on many a bloody academic field, this biography’s perspective is a little different: it shows Joseph as a more reactive figure, propelled, to a degree, by his compulsive reading, but also by the force and sheer vituperative zeal of the Alfred Sherman phenomenon.

An ex-Marxist and Republican volunteer in the Spanish Civil War, Sherman is not a man who believes in half-measures. By the Seventies he was a right-wing polemicist, as anxious to destroy the old Tory establishment as to bury socialism and quite prepared to get down to names and cases. Halcrow, who is a former deputy editor at Sherman’s old stable, the Daily Telegraph, describes him as ‘looking like most Englishmen’s idea of an alien’. Either for that reason or, more probably, on account of his loud, contentious and persistent style of dialectic, Sherman was not every right-wing person’s cup of tea during his period at the Centre for Policy Studies, which had become the intellectual power-house of the New Conservatism. But, as Halcrow portrays it, it was he who gave to the Centre’s work its unquestionable punch. He also wrote most of Joseph’s influential series of speeches setting the tone for the Thatcher decade that was to follow. Not altogether surprisingly, very little house room was found for Alfred Sherman once the Tories were in power, though in time a knighthood followed; by then, Keith Joseph had long since ceased to be Sherman’s knight in shining armour.

Before Margaret Thatcher had occupied the empty stage, however, and when Tory MPs were desperate to find even a half-way credible candidate for the leadership who was willing to stand against Heath in the first new-style party election, there had been a short interval during which Keith Joseph’s name had been on every lip. He was just about to deliver a major speech at Birmingham, where Enoch Powell had cut himself off from any possibility of leadership seven years before. The circumstances ensured maximum media coverage. Most people found the speech very strange indeed. The major part – attacking the ‘permissive society’, commending Mrs Mary Whitehouse, undertaking to fight the battle of ideas in every school, every university, every publication, every TV studio in the country – was written by Sherman, but Sir Keith had added a final section of his own. It was based on something he had just read but resembled something that he had said before. ‘The balance of our population, our human stock, is threatened,’ he proclaimed. ‘A high and rising proportion of children are being born to the mothers least fitted to bring children into the world and bring them up.’ From that moment the ‘Joseph for leader’ movement was stone dead; the door was open for Margaret Thatcher.

Mrs Thatcher, on coming to power, despatched Joseph to Industry, a department which, Sherman pointed out, ought not, under New Conservative principles, to exist. His two-year tenure is principally remembered for the reading-list with which he supplied his senior civil servants. Halcrow performs a service by reproducing it. It contains 29 titles, two of them by Adam Smith and eight by Keith Joseph. The sharpening-up processes of Opposition did not make decisions any easier for him in office. Too often his open-mindedness, his receptiveness to many different points of view, his delight in long and at times self-lacerating discussion, ran against the full flowering of his conviction politics. At each of his major jobs there was one radical decision in keeping with his beliefs that he did not take: in Housing it was abolition of rent control; in Industry it was to end the subsidies to British Leyland and to let it, if need be, go bust; in Education it was the failure to introduce education vouchers. The image of Joseph in Opposition sitting at the CPS ‘with his head in his hands being verbally lambasted by Alfred’ is replaced by the image of him being bullied mercilessly in Cabinet by the Prime Minister in front of his colleagues. Still, there were a number of achievements, including the beginning of the process of privatisation, before he moved on, at his own request, to Education, where he stayed for five tempestuous years.

The idea of financing education with vouchers in the hands of parents struck Sir Keith as the one lever that could transform attitudes. An immense intellectual effort both inside and outside the department – shoals of outside experts were enlisted – was devoted to producing a workable plan. It was a cranky and politically perilous idea, but not more so than the poll tax, which has been persisted in. Yet at the end of it all Joseph could not see his way through. His main trouble at the Department of Education was that his reading told him that Britain’s economic defeats had their origin on the playing-fields of her school system. He wanted to reverse the situation in a fundamental way, but revolutions in policy do not come cheap and Joseph believed as a matter of principle in cutting the rates of taxation and lessening the functions of government. He therefore thought himself in honour bound to set a good example by refraining from appeals against Treasury budgetary limits along the lines of education being a special case. This approach committed him to a perpetual feud with the teachers’ professional organisations over pay. Still, he did identify important problems – like the bottom 40 per cent of pupils who passed through the school system without acquiring any qualifications, weakness in the teaching of science, and the need to set minimum standards that would be achieved by 80-90 per cent of pupils – and he started trends taken over by his successors.

Keith Joseph was to acquire an increasingly hunted and beleaguered look. His voice had become quite hoarse, his features betrayed the torture of too many agonising decisions. One in particular had involved him in a confrontation with Tory backbenchers from which he emerged very much the worse for wear. He had proposed to touch the budgets of the better-off parents of university students by having them share in the costs of tuition; he wanted the money to finance more research. In 1986 he decided to retire, intellectually honest as always and unsparing of himself (asked whether he left the Department of Education with a sense of achievement, he answered ‘No’), the baffled conscience of Thatcherism.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.