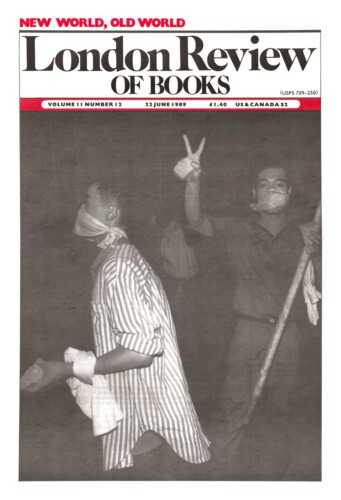

In the early summer of 1981 a string of riots burned up and down Britain like Armada beacons. Brixton resembled post-Blitz London. Whole areas of Manchester, Preston, Wolverhampton and Hull were reduced to rubble and glass. In July, Liverpool lit up in a haze of flame and CS gas. Shortly afterwards Manchester erupted once again.

The Home Secretary at the time was William Whitelaw. He did what politicians tend to do in such circumstances: dropped in for a series of flying visits. In Liverpool the Chief Constable insisted that the visitor did not leave the official car, for fear of sparking off yet another riot. As Whitelaw drove back South after a subsequent trip to the Moss Side area of Manchester, his detective tuned into the Police network and found it ‘choked with troubles’. Mr Whitelaw was choked with foreboding, the sort of foreboding he had experienced during his years of political activity in Belfast. ‘There was a suppressed atmosphere of impending doom, and an unexpressed fear about where it would all end ...’ Mrs Whitelaw was at Dorneywood, the official residence near Slough. When her husband arrived home, she did her best to cheer him up, and made him a meal after which he gave himself over to his thoughts on what he had witnessed.

I remember sitting out after supper on a beautiful hot summer evening, looking at the fields and trees of Burnham Beeches. It was a perfect, peaceful English scene. Was it really the same country as the riot towns and cities which I had visited during the week? Was it really the same vicinity as parts of London a few miles away which at the moment were full of troubles? Surely, I thought, this peaceful countryside represents more accurately the character and mood of the vast majority of the British people.

There is something touching about this trust in an English Arcadia as a bulwark against the awful grossness of the post-industrial urban reality. The English pastoral into which it fits is that of troops reading Country Life in the Flanders trenches. It is that of the voice of Edgar A. Guest in 1918, in The Things that make a Soldier great:

What is it through the battle smoke the valiant soldier sees?

The little garden far away, the budding apple trees.

Then there is Sassoon’s Sherston in Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, when he has been subjected to the Scottish major’s lecture on the Spirit of the Bayonet:

Afterwards I went up the hill to my favorite sanctuary, a wood of hazels and beeches. The evening air smelt of wet mould and wet leaves; the trees were misty green; the church bell was tolling in the town, and smoke rose from the roofs. Peace was there in the twilight ... But the lecturer’s voice still battered on my brain. ‘The bullet and the bayonet are brother and sister. If you don’t kill him, he’ll kill you.’

England, you see, isn’t Brixton or Toxteth. It is roast beef and Yorkshire pudding and the smack of leather against willow. Writers use pastoral when times are hard. As Paul Fussell points out in his Great War and Modern Memory, it is ‘a way of invoking a code to hint by antithesis at the indescribable ... at the same time, it is a comfort in itself, like rum, a deep dug-out, or a woolly vest.’ With Mr Whitelaw, it is both a comfort and a source of inspiration. What, he asked of himself that Friday evening at Dorneywood, does the real England expect of its leaders at such a time – ‘a disgraceful episode in our nation’s history’? The answer supplies itself: ‘Determination and firm action calmly taken.’

What was Willy himself if not the country’s own deep dug-out and woolly vest? For years he has padded faithfully around the political scene like an old English sheep dog, the reminder of a different sort of Britain and, more important, a different sort of Conservative Party. Those who thought domestic politics had taken a distinctly un-English turn with the advent of Mrs Thatcher were comforted by the large, clubbable, bloodshot figure at her side. It was an impression that Willy himself did nothing to discourage and may even have nurtured. He managed with consummate ease to give a sense of perfect loyalty and to induce, simultaneously, the niggling thought of what she’d be getting up to if he weren’t around. It was an impressive piece of political juggling. Now that the old boy has spilled the beans on the past decade, what was he really up to here? Of course, we are no nearer knowing. If there is a single bean spilled in The Whitelaw Memoirs this reviewer has missed it. One certainly looks for coded beans as well as the more overt sort. But if there is a code, then it is of an obscurity to defeat the most devoted cryptoanalyst. The book, in short, is about as dull as it could be. This is a comfort as well as a disappointment. It is disconcerting when old English sheep dogs start behaving as though they were pit bull-terriers. William Whitelaw is a gentleman, and gentlemen do not write the sort of book that is serialised in the Sunday papers. At the same time, he is a quite sufficiently astute politician to have ensured that the serial rights were, indeed, purchased by a Sunday paper.

The writing is of the ‘I am often asked’ school. ‘I am often asked such and such and my reply is such and such ... In another context I am often asked so and so and my reply is so and so.’ Or it might be described as the ‘Here I must pay tribute to’ school of writing. ‘Here I must pay tribute to X whose unswerving loyalty and great ability ...’ If the book were not so evidently dictated (here we may pay tribute to Mr Whitelaw’s secretary, Liz Huckle, who typed it from the manuscript), one might almost believe that the author was using a word-processing programme with a ready-programmed tribute button.

The book is as short on insights as it is on beans. He has few original reflections on Northern Ireland: he is interested in the Police response to the aforementioned riots, but remarkably free from curiosity as to what caused them. He has little interest in Abroad and would have hated the job of Foreign Secretary ‘because I dislike travel and much prefer this country to any other’. The Falklands War, in which he was intimately involved as a member of the select Cabinet sub-committee, is dealt with in nine bland pages. The chapter on golf stretches to ten. Willy Whitelaw’s political life took in civil war in Northern Ireland, the Falklands War, and a succession of riots, sieges and other turmoils. Out of all this, the incident which evidently caused him the most anguish is the discovery of a man in the Queen’s bedroom during his Home Secretaryship. The interim political epitaph must be his own description of his Parliamentary appearances as Mrs Thatcher’s deputy: ‘It was my purpose not to score runs but to keep the political ball out of my wicket.’ It may be that a more generous judgment may eventually be expressed: but for that we shall have to wait for a more reflective writer.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.