The first picture in Richard Avedon’s folio is captioned ‘Alan Silvey, drifter, Route 93, Chloride, Nevada’. Such photographs were taken in the Dustbowl fifty years ago. But this is art, not documentation. We have learned a lot about photography since the Thirties, and now no one believes that truth is simple – ‘all photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth’ is Avedon’s way of putting it. On the other hand, no one really doubts that photography is art. Meanwhile, in these pictures of the anonymous and deprived, ethnography and fashion join hands.

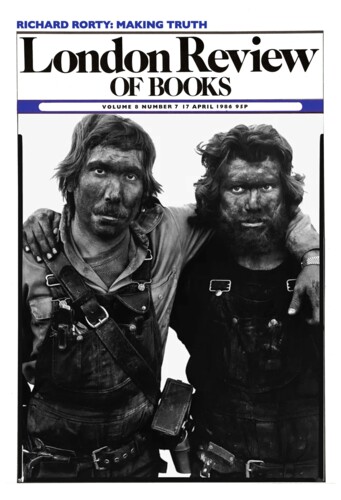

Fashion photographers are famous for stopping girls in the street, and making their faces their fortunes. Avedon, who has taken some of the best fashion pictures, looked for these less fortunate Western faces in crowds. In a sparsely populated country, fairs and festivals – any places where Westerners gathered – were his recruiting grounds. But there are, as well, prisoners, miners, slaughterhouse workers and hospital patients. All were chosen, like extras in a movie, because their faces seemed to hold a message.

Photography has been lucky in its commentators – Barthes, Sontag and Malcolm. But next time it is up on the old charge of exploitation and fraud I would have the judge read Avedon before he turned to the critics. The few paragraphs in which he describes how he took the pictures for In the American West are the best account of the photographer’s craft I know. They are relevant to work very unlike his own – to Cartier-Bresson’s collection Photoportraits, for example.

The arena Avedon works in is execution yard and interrogation cell as well as stage and studio: ‘I photograph my subject against a sheet of white paper about nine feet wide by seven feet long ... I work in the shade because sunshine creates shadows, highlights, accents on a surface that seem to tell you where to look.’ This explains the even, clinical light which bathes the portraits. Nothing is in shadow. The finest details of skin and cloth – every pore, every wrinkle, every hair – are clear. Photographs taken in the same light have the same texture: this distinguishes the work of one photographer from that of another. Cartier-Bresson, who follows his subjects about, might be thought to have no control over light. This is only partly true, for the prints made for him limit the range of black to white (are, in photographic terms, ‘soft’), and both bright sunlight and dim interiors are recorded in pearly greys. Avedon:

I use an 8x 10 view camera on a tripod ... I stand next to the camera, not behind it, several inches to the left of the lens and about four feet from the subject. As I work I must imagine the picture I am taking because, since I do not look through the lens, I never see precisely what the film records until the print is made. I am close enough to touch the subject and there is nothing between us except what happens as we observe one another during the making of the portrait. This exchange involves manipulations and submissions. Assumptions are reached and acted upon that could seldom be made with impunity in ordinary life.

A big camera produces very detailed negatives. Another texture is established. This regularity is reinforced if the whole negative is used: Avedon’s prints have a black border which is in fact the unexposed edge of film which was under the frame of the negative carrier. Cartier-Bresson will not allow his prints to be reproduced cropped: his format, too, is fixed. It is a commonplace to say the camera does not matter, that the photographer is what counts. But different cameras put the photographer in a different relationship to his sitter. Avedon’s method sets up one kind of drama: Cartier-Bresson’s miniature camera another, which allows him to move about, and to see exactly what is in the frame. His pictures are visually more contrived, they are painterly compositions. Avedon’s pictures are dramas, presences, not arrangements. Consistencies of craft are a prerequisite of photographic style. By limiting and refining their means photographers assert their identity.

A portrait photographer depends upon another person to complete his picture. The subject imagined, which in a sense is me, must be discovered in someone else willing to take part in a fiction he cannot possibly know about. My concerns are not his. We have separate ambitions for the image. His need to plead his case probably goes as deep as my need to plead mine, but control is with me.

This explanation of Avedon’s confounds the notion that the photographer – or the portrait painter – explores the character of the sitter. Avedon’s fashion pictures made clothes seem wonderful, strange, desirable. No one thinks the fashion photographer explores the model’s personality, and portraits are no different. The fashion photographer’s chant (‘a little to the left, now standing up, wonderful’) and the portrait photographer’s (although the latter often prefers silence, finding that the best portraits are of uneasy sitters) are ways of making the subject perform. The ambitions of subject and photographer are both legitimate; the control, as Avedon says, is in the hands of the photographer.

It is for this reason that Cartier-Bresson’s way of working produces no greater truth than Avedon’s. A difference between the two collections is that many of Cartier-Bresson’s sitters are famous: Sartre, Bonnard, Carson McCullers, Edmund Wilson. The pictures seem to reinforce what we know of the sitters, and also to be direct evidence of the truth of what we know. But the evidence is really little more direct than the evidence David’s portraits give us of revolutionary frankness, Gainsborough’s of the charm of actresses, or Reynold’s of the integrity of colonels. Significantly, it is the photo-reportage conventions of Cartier-Bresson which are turned to when photography is used as propaganda and shows public faces (John F. Kennedy, for example, or Anwar Sadat) in private places looking kind and nice.

Avedon’s West pictures, with only one or two exceptions, show a person or a couple standing square on to the camera: they are full face, and sometimes show the hands, never the feet. The narrow box of space (between camera and background paper) which is in focus captures the sitter like a bug pressed between microscope slides. The eyes look straight out at you, and the fine detail of the photographs is like that of many Flemish portraits. But the full-face pose and earnestly questioning eyes are like those in Romantic self-portraits – those of David and Samuel Palmer, for example.

Nearly all the Cartier-Bresson portraits are three-quarter face. The sitter does not acknowledge the camera. The depth of field is great: things close and far away can all be in focus, and there is no need for the photographer to instruct the sitter about where to stand. But this difference is less important than the common quality of timing. Avedon waits for Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’. But it will be the moment when the tension is right, not when the composition, like a Degas study, falls into place.

Among Avedon’s portraits two pictures of bloody skinned sheep and calf heads are inserted – unexplained, brutal and effective. The fastidious mechanical reproduction of the faces of a few dozen Americans, made in conditions of manipulation and submission, demand comparison with Van der Weyden or David. The animal heads, like the meat painted by Goya and Soutine, suggest the animal nature of all the other subjects. But in the comparison is a reason for the disquiet the book leaves one with. The human attachment of artist and subject which Goya’s and even Soutine’s portraits imply is excluded from Avedon’s encounters. Even as you admire these photographs you fear for the culture that made them.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.