Marguerite Yourcenar was born in Brussels in 1903. She became a US citizen in 1947 and has lived for more than thirty years on Mount Desert Island, off the coast of Maine. Thus when she was proposed for membership of the French Academy, it was natural that some Frenchmen would make an issue of her nationality, in order to prevent a woman joining their club. However, the justice minister granted her dual nationality on the grounds of her ‘evident cultural links’ with France, and in 1980 she became the first woman member of the Academy. In that same year, Les Yeux Ouverts: Entretiens avec Matthieu Galey was published in Paris. Galey, a French journalist, had been to interview her on Mount Desert Island. The title of the book was a quotation from Mme Yourcenar’s novel, Memoirs of Hadrian: ‘Let us try, if we can, to enter into death with open eyes.’

The translation of M. Galey’s interviews has been made by Arthur Goldhammer, working with the nervous precision demanded by his knowledge that Mme Yourcenar is herself a fastidious translator: she has translated The Waves and What Maisie Knew into French. With Open Eyes is an engaging introduction to her work, imbued with an unexpected spirit of comedy, rather like Boswell’s life of Johnson – for Mme Yourcenar, like Johnson, is a weighty and judicial writer, contemplating many eras and continents, while Matthieu Galey is a journalist determined to ask ‘Just exactly how do you feel?’ about the issues of the day. In the Twenties, every interviewer asked his subject for views about the Modern Girl. In the Sixties he might ask: ‘What do you think of people who “trip” with drugs?’ or ‘Were you something of a “hippie” before the fact?’ Galey does indeed ask two of those questions, in those very words – just as Boswell would have asked Johnson, hoping for a weighty reply. Though Galey does not ask about the Modern Girl, he does ask about feminism – and also, of course, about racism, another issue of the day. She responds by questioning the journalist’s categories, not discourteously, but sometimes like a tutor with a student. If he uses a Latin or Greek word, like ‘pessimist’, ‘anthropomorphic’ or ‘aristocratic’, she asks him to think what the word means. We learn that her father began teaching her Latin when she was ten and Greek when she was 12. (Her mother died in childbirth.) She is not uncivil but I lost count of the number of times she said no to his suggestions.

Galey likes the idea of Mme Yourcenar being a Flemish ‘aristocrat’ in romantic exile from the Paris where she truly belongs. Her father’s name was Michel de Crayencour (her pen-name being a near-anagram) and she lived in a grand house with many servants. ‘This Flamande knows her ancient charters,’ writes Galey, ‘but doesn’t care a fig for aristocratic origins or fancy genealogies.’ It has been recognised in Paris by ‘even the most partisan newspapers and weeklies’ that ‘the time has come to admit that while Yourcenar might be an aristocratic writer, she is an aristocrat worthy of praise ... This is how reputations are made in France.’ But what is she doing out there on Mount Desert Island, so far from the Paris publishing houses of ‘the Sixth Arrondissement with its schools, its vogues, its commitments’? He keeps reverting to her isolation from the Parisian well-spring. She tells him about the people of Mount Desert Island and about its history, from Champlain who named it in the 17th century to John D. Rockefeller, but he still can’t accept it as a real place. When she talks of her friends, he asks: ‘Do they come even to a place as out-of-the-way as this?’ As if exasperated, she replies: ‘Let’s not rehash the myth of my solitude yet again!’

The European wars led her to England in 1915 and to America in 1939: she is altogether well travelled. Galey cannot reconcile this taste for travel with her habit of disciplined contemplation, surely a stay-at-home thing to do. She responds: ‘It’s becoming increasingly difficult to follow you. One travels in order to contemplate. Every trip is contemplation in motion.’ Galey remarks that ‘some great thinkers never left their studies: Descartes sat by his fire, and Montaigne had his library.’ She replies: ‘As it happens, the two men you mention both travelled fairly extensively.’ Like a tutor she tells him all about it, starting with Descartes’s war service in Holland. We could re-title this book after Denis Johnson’s play, The old lady says ‘No!’ All the same, Matthieu Galey (perhaps faux-naif) does elicit a good deal of information with his mistakes and his provoking questions. He even tempts her, for a moment, into a touch of French snobbery: she admits she is glad she was named Marguerite and not, for instance, Chantal – ‘a saint’s name, but it smacks too much of the Sixteenth Arrondissement’.

Talking seriously of her work, she most frequently refers to Memoirs of Hadrian, which she completed on Mount Desert Island. She opened a trunk in 1948 and found in it a few pages she had written about Hadrian and with them a volume of Dio Cassius and a copy of the Historia Augusta. She found herself able to ‘put herself in the place’ of Hadrian, writing in the first person, under his name – not like one of those historians who are ruled by theories, militarists admiring imperialism or Marxists seeking communism or its absence. ‘I reconstructed a day that Hadrian spent in Palestine with the same concern for the truth as in writing about a day in the life of the Crayencours.’ Galey asks: ‘How is it possible to relate individual destinies to the context of history, to life’s ebb and flow?’ She counters: ‘How is it possible not to? You seem to be making an idol of “History”, as the Marxists do. History consists of individual lives ...’

When her book was published, a classics master told her he had set passages for his pupils to translate into Greek. She tried this herself. ‘I soon discovered that certain French sentences went into Greek quite readily, but one or two did not, because they were my sentences, not Hadrian’s.’ When she is complaining about the French attitude to ‘love’, asserting that men (if not women) ‘have always felt that there were other things in life and in the world than love’, Galey asks: ‘how do you account for the fact that all literature, including your own work, revolves around this problem?’ The old lady says ‘No’. She admits that ‘in Hadrian many readers focus on the story of Antinous, which is of course a love affair, but in fact it takes up only one-fifth of the book ... It is possible to imagine writing Hadrian’s memoirs without dealing at all with the subject of love ...’ Hadrian was a man who ‘spent 20 years of his life trying to stabilise the earth’.

Galey still thinks that male ‘homosexuality’ seems to be a pressing concern of hers and he mentions Zeno, a character in her novel, The Abyss, a sort of ‘spoiled priest’ of the early Renaissance. She explains that Zeno was ‘not what we today call a homosexual, but a man who from time to time had adventures with other men’: he was like Hadrian in this, but Zeno under the Church’s authority was indulging a ‘subversive’ taste for ‘adventure’, while for Hadrian such a problem did not exist. (She has an interesting parenthesis here concerning the Roman Church’s self-confidence about sex-laws, contrasting the present Pope’s confidence about contraception with his reluctance to denounce Belfast terrorists.) But Hadrian, in another time from Zeno’s, merely ‘prefers to seek his lovers outside the rather hermetic world of women, which he thinks of as frivolous and hopelessly domestic ... This doesn’t however prevent him from having mistresses, some of whom leave him charmed memories.’

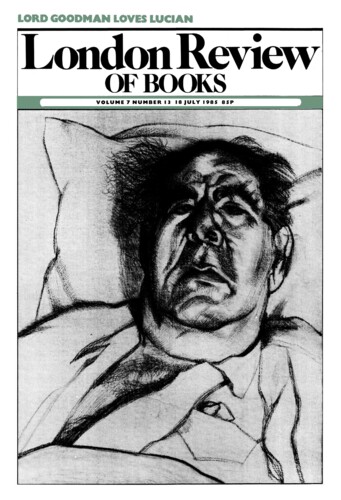

‘Having identified yourself with Hadrian,’ asks Galey, ‘how did you bring yourself to accept the executions, crimes and other deeds committed out of political necessity?’ She replies: ‘One has no choice ...’ She goes on to assert that Hadrian’s crimes were ‘hardly crimes at all compared with what we have seen and are seeing still, but mere excesses of severity ...’ This passage is relevant to the ruthlessness of other characters in her work, accepting the cruelties of their time. She remarks that she first saw Hadrian’s face in London in 1915, at the British Museum: ‘a virile, almost brutal bronze which had been fished out of the Thames’. Later in the book, when offering Galey a lyrical collage of splendid moments in her life, she includes ‘a day at Corbridge in Northumberland when, having fallen asleep in the middle of an archaeological dig overgrown with grass, I passively allowed the rain to penetrate my bones, as it penetrated the bones of the dead Romans.’ Corbridge is on Hadrian’s Wall.

The Romans in Britain recur within her newly translated book of essays, Sous Bénéfice d’Inventaire, which has been given the title The Dark Brain of Piranesi. She first began to study Piranesi when she saw his 18th-century drawings of the Villa Adriana, encrusted with roots and brambles, and the cliff-like foundation wall of Hadrian’s tomb. Besides Piranesi she discusses Cavafy, whose Greek poems she has translated into French, and Thomas Mann, whose manner of dealing with antiquity (as in Joseph and his Brethren) she perhaps assimilates to her own way of dealing with Hadrian’s world. Galey suggests as much. ‘Are you sure that there’s no “autosuggestion” in your conception?’ he asks. ‘How could I possibly maintain that I’m “sure”? ’ she replies. Then there are inviting introductions to the work of Selma Lagerlöf, a Swedish authoress, written with a generous sort of feminism; and to Agrippa d’Aubigné, a French poet of Protestant persuasion, concerned to celebrate the martyrdom of his contemporaries, like Cranmer, burned in Oxford, and William Gardiner, burned in Lisbon. ‘Une rose d’automne est plus qu’une autre exquise,’ Mme Yourcenar remarks, ‘was written not by Ronsard to celebrate some aging beauty but by d’Aubigné to glorify a belated martyr of the Reformation’. When d’Aubigné escaped burning, through the offices of a defrocked monk, ‘out of sheer bravado he danced a galliard to the music of his captors’ violins’: he was about twelve at the time. Then there is an essay about the history of a French château, concluding with one of her eloquent variations on the ‘What-about-the-workers’ theme. But of these seven essays the one most obviously relevant to Hadrian is her appreciation of the Historia Augusta.

This is not a very well-known book, partly because it is so bad. It is a history of Roman emperors, from Hadrian to Diocletian, by an unknown author (or authors, with false names), compiled in the fourth century, perhaps. In 1980 Ronald Syme in the London Review denounced it as a hoax. There is a Penguin translation by Anthony Birley, called Lives of the Later Caesars. To dip into it is rather like finding old newspapers under the lino, from 1956 or 1968, say, with time-serving editorials, eulogies of American Presidents, moralising news-stories by journalists missing the point, all mixed up with gossip-columns and horoscopes. All this Mme Yourcenar is glad to admit. Nevertheless, there is truth in the Historia Augusta and even from the lies and rumours there exudes ‘a dreadful odour of humanity’, she says. ‘No book ever reflected so well as this leaden and all-absorbing work the judgments of the man-in-the-street and the man-on-the-backstairs as to the history of the moment. We have here public opinion in the pure state – which is to say, impure.’

There is ‘an exasperating moralism’ about it, like that of a Conservative newspaper: the ‘crime’ of eating expensive fruit out of season is put on the same level as fratricide or political assassination, by an author with ‘educated’ mannerisms expressing ‘the pompous misery of a culture consisting of no more than a schoolboy’s anthologies’. Yet we catch so many glimpses that seem to authenticate themselves. Sometimes, as she says, ‘a certain poetry rises out of this mass of grim details, like mist from the bare ground.’ She sees the Emperor Severus in Carlisle, witnessing the omens of his death – the black Moorish soldier capering before him, the two black bullocks brought out for sacrifice by a provincial ignoramus at the temple of Bellona: when the African emperor rejected them the black bullocks followed him to his doorstep. The story could be easily rejected as a feeble concoction, Birley has written elsewhere, but he finds that there was indeed a Moorish unit near Carlisle at the time, and a temple of Bellona hard by. So Mme Yourcenar is justified in imagining ‘a cold or rainy February day on the Scottish border, the emperor in military garb, his African complexion blanched by disease and the northern climate, the two placid bullocks ... ignorant of this human world and this alien man for whom they augur death, clambering through the muddy alley-ways of this little garrison town before returning to their wild hillside’. That is the way she uses the Historia Augusta in her essay – and that is the way she used it for Memoirs of Hadrian.

‘This poetry,’ she says, ‘is a poetry we ourselves extract.’ She seems to think of poetry, not only as an artefact, but as something existing in the world to be caught by those who are capable. She told Galey: ‘For me a poet is someone who is in contact, someone through whom a current is passing.’ (She goes on, of course, to offer useful advice about actually writing it.) There is something similar in her study of Piranesi’s drawings of imaginary prisons, contemplating his Swift-like sense of human futility and his dream-like obsession with punishment, noting that practical George Dance used the drawings when designing Newgate and that De Quincey, recalling Coleridge’s commentary on them, got the facts wrong but captured the spirit of the drawings, believing them to represent Piranesi’s dreams. ‘Thus the dreams of men engender one another.’

When she writes of Mann, she draws him into her world of alchemy. (The French title of The Abyss is L’Oeuvre au Noir, an alchemists’ concept.) Perhaps, too, there is a fellow-feeling with Mann when she writes of the ‘insidious’ quality of his eroticism, his willingness or need to use ‘identity of sex in lovers or disparity in their race or age’. But she told Matthieu Galey that the sex of the beloved was not a pressing concern of hers. ‘It was the sexual aspects that aroused or shocked readers when Cavafy’s poems first appeared,’ she says, ‘but in Greece nobody talks about the sexual content any more. It’s comparable in some ways with Baudelaire. What counts is Baudelaire’s genius, nothing else.’ In the same way she told Galey that age is not her ‘concern’, nor is class. I think she means that she is not going to be oppressed by others’ conceptions of age, class or sex – for, of course, she writes about all three, with thought and originality: she is simply rejecting journalists’ use of these categories. In her essay on Cavafy she does discuss his sexual preference – and it is not surprising that Galey should keep pressing her about her work on the theme of ‘identity of sex in lovers’.

We have here new translations of two of her novels. Her first, Alexis, is in the form of a letter from a young man to his wife who has just borne him a child: he is trying to explain that he must leave her because he falls in love with men. ‘In fact, I did not love you. Yet you became very dear to me. I have told you how sensitive I am to women’s sweetness ... With the utmost humility, I ask you now to forgive me, not for leaving you, but for having stayed so long.’ Mme Yourcenar wrote this book when she was 24. The title is a reference to Virgil’s poem about two young men, beginning: ‘Handsome was Alexis and the shepherd Corydon burned with love for him.’ Gide wrote a story called Corydon and Mme Yourcenar wrote another called Alexis. She says she was not much influenced by Gide because, like many thoughtful young people in different centuries, she read older books and knew of contemporary writers only through the modish fuss surrounding them: her Alexis is the same sort of ‘young fogey’, with his old-fashioned style. Galey says Alexis’s style is glacial. No, she says, it is tremulous. ‘People often say you write in marble or bronze.’ No, she replies – ‘except perhaps in Hadrian, where the polish comes from Hadrian’s era and from the lapse of time’: with other books she has felt she was working in granite, or kneading a very thick dough (‘Remember that I make my own bread’). Galey asserts that over the years ‘your diction has remained unchanged.’ The old lady says ‘No’ again.

To judge from the authoritative translations, she is surely right about this. Erick, the narrator of Coup de Grâce, says things Alexis could never say: ‘Our men were certainly not lacking in invention,’ he remarks, ‘but so far as I was concerned I preferred to deal out death without embellishment, as a rule. Cruelty is the luxury of those who have nothing to do, like drugs or racing stables. In the matter of love, too, I hold for perfection unadorned.’ This self-armoured soldier is a Prussian with French and Baltic blood in his veins: he is fighting in Courland in 1919. Courland? It is part of Latvia which has become, in Erick’s unmodern, non-political eyes, what it had formerly been, ‘an outpost of the Teutonic Order, a frontier fortress of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword’. He is fighting Bolsheviks in a world of confused categories – for we remember that young Colonel Alexander, later Lord Alexander of Tunis, was out there too, commanding 6000 men of the German Landeswehr.

Yet hard Erick has something in common with soft Alexis, besides their almost stateless tribalism – for Alexis is a musician of poor but proudly connected Bohemian family, with a Moravian prejudice against the Austrians of Vienna. Erick is being pursued by a woman he does not love, the sister of his best friend. When he rejects her, she goes over to the Bolsheviks, with a Jewish Communist friend. Captured among her comrades, she has to be shot, and she asks that Erick should despatch her. This is the coup de grâce.

The plot may sound like an opera summary, but there are no arias. Erick tersely explains his rejection of the girl: ‘I was not prepared to regard Conrad as a brother-in-law. One does not drop a friend of 20 years’ standing, though radiantly young, for a shabby intrigue with his sister.’ Erick looks with regret at the girl he must kill: ‘that body, so alive and warm, which the intimacy of our life together had made almost as familiar to me as the body of any soldier friend’. The book is a sort of portrait of this girl, mediated through the lucid monologue of this infuriatingly bloody man. He is sorry she will bear no children, to carry on ‘her courage and her eyes’. But then, ‘who wants to people the stadia and the trenches of the future?’ He is sorry too to see the dead body of her Jewish friend, with Rilke’s Book of Hours in his pocket – ‘probably the only man in the land at the time with whom I might have had half an hour’s decent conversation’.

This masterly novel (revised in 1963) was first published in 1938, when Mme Yourcenar was expecting war and, no doubt, thinking about Germans, Jews and Communists. ‘One would have had to have been deaf and blind not to have seen the war coming in 1938,’ she tells Galey, but whenever she returned to France from her travels abroad, she ‘saw people sitting in the cafés who gave no sign of suspecting that anything was amiss’. French writers seemed equally insensitive about Mussolini’s Italy, which she had exposed in her novel of 1934, A Coin in Nine Hands: they had a lyrical approach to Romanness, ‘described in the most orotund way. They spoke of what they liked to call a tradition of grandeur and saw nothing of its bombastic, fraudulent side. What I tried to show in my book was above all the life of the common people.’

Her ‘what-about-the-workers’ attitude crops up even when discussing men. Galey, with glib feminism, remarks of a rape in the national park: ‘A man wouldn’t have run the same risk.’ Mme Yourcenar replies: ‘But he would have run others: the danger of war, of working in a mine, of doing dangerous jobs hitherto rarely open to women. I’m thinking just now of two quarry workers from this island who were buried alive in a rock slide.’ When Galey asks her why America does not appear in her work, she replies: ‘A little of it does appear in the form of an enslaved and mistreated race, in my translations of Negro spirituals, Fleuve profond, sombre rivière.’ She recognises that her black readers have a ‘natural and very healthy sort of reaction’ against those songs, but she urges them most eloquently to think again about this ‘magnificent music. In the atrocious conditions of slavery, this kind of fervour was, in a sense, a gift from God.’

She is by no means out of touch with issues of the day, noting that work on her 16th-century novel, The Abyss (influenced by her experience of the black American prophet, Father Divine), was begun in 1956 – ‘Think back. Suez, Budapest, Algeria ...’ – and published in 1968, the year of international rebellion against the Vietnam war.

When Galey tries to place her in some ‘Left’ or ‘Right’ Parisian category, she instructs him about ecology and conservation (‘The name of Ralph Nader is little-known in France ...’) and the malevolent influence of television and advertising (‘I don’t need salesmen coming into my house to hawk their wares ...’). He asks: ‘Would you go so far as to outlaw advertising? In that kind of society would there be a place for writers? They too are a luxury.’ She says: ‘No. Genuine writers are a necessity ...’ She does vote in America, while aware she is ‘taking positions on phony issues and voting for men whose worth I am not in a position to judge. The two parties look more like rival clans than political organisations.’ He suggests that if she wants to campaign against the politics of advertising and the media, she has not come to the ideal country. ‘I don’t know about that,’ she says. ‘Perhaps I have. What is nowadays most frightening to contemplate is the effect of advertising and the media on the poor countries.’ This is a sound point, for in America is surely the well-spring of the international dangers she fears. But Galey is inclined to suppose that conservation is only for ‘Conservatives’ and that her ecological activity and expenditure must take the form of a rearguard action. ‘I would say it’s more in the nature of an avant-garde action,’ she replies, ‘the purpose of which is to lay the groundwork for a cleaner, purer world to come.’

I should add that her Nouvelles Orientales of 1938 has just been published in America as Oriental Tales in a new translation by Alberto Manguel, with some revisions and some supplementary material. The collection will be published in this country in September,* to coincide with an Omnibus profile, on BBC Television, of Yourcenar and her work. Of these ten stories some are based on legends and literature of ancient China, India and Japan; others on Medieval ballads of the Balkans or on Greek folklore of the 1930s; the least ‘oriental’ is a story about a Dutch painter (contemporary with Rembrandt) who has indeed travelled in Asia Minor but who earns his place in this book through his relevance to another story, ‘How Wang-Fo was saved’, a Taoist fable about another painter in Imperial China. Mme Yourcenar has revised the Indian story ‘to better emphasise certain metaphysical concepts’ and has omitted one story, ‘The Prisoners of the Kremlin’, with which she had hoped in 1938 ‘to reinterpret in a modern way an ancient Slavic legend’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.