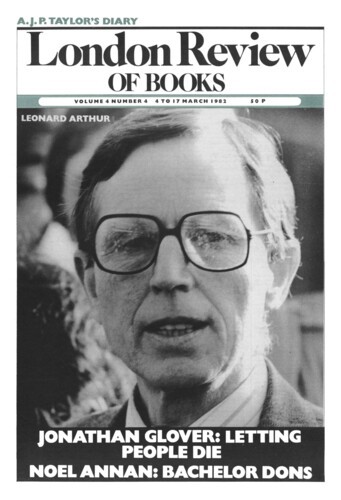

On 5 November last year, Dr Leonard Arthur was found not guilty of attempting to murder John Pearson, a baby with Down’s syndrome, who had died while under his care. Mrs Nuala Scarisbrick, the Hon. Administrator of LIFE, commented: ‘The verdict gives carte blanche to doctors to give treatment to patients who are unwanted or handicapped or both, that will result in their death. Now to be unwanted is to be guilty of a capital offence.’

It is worth looking back at the trial and at the debate which followed. The verdict does not license Mrs Scarisbrick’s dramatic conclusions about the present state of the law. It is not obvious that the verdict has clarified the law at all. But the debate tells us something about our society and our habits of thought. The facts of the case are widely known. The baby’s parents did not want him to live. Dr Arthur had written,‘Parents do not wish the baby to survive. Nursing care only,’ and had prescribed a pain-killing drug. The baby contracted pneumonia and, whether or not as a result of this, died. A member of the hospital staff reported the matter to LIFE, so initiating the events leading to Dr Arthur’s prosecution. The original charge was murder, the prosecution claiming that the drug had been used intentionally to kill the baby. But during the trial it became clear that the drug could not be proved to have caused the death, and the charge was reduced to one of attempted murder.

The verdict, although predictably criticised by LIFE, gave grounds for relief. Throughout the case, it was unchallenged that Dr Arthur had acted from the most humane of motives, and, as the judge said during the summing-up,‘seldom in a court could one have heard so many testaments to a man’s good character, his gentleness, his skill, his consideration for others.’ A verdict of guilty would have been a morally undeserved calamity, an appallingly hard response to such a doctor trying in good faith to cope with a human disaster. The verdict was also welcomed on wider grounds. The hope was expressed that doctors faced with these decisions might now be free from additional worries about prosecution, and that the verdict might end LIFE’s practice of encouraging nurses and others to become informers against doctors.

Relief at the avoidance of a harsh injustice is appropriate. But the wider hopes may be unfounded. Members of LIFE have expressed the intention to continue as before. And the legal position may be less secure than doctors would wish. Even if the verdict, with no appeal to a higher court, could be taken as definitive, it is unclear what it could be taken to establish. The defence case rested on contentions about the drug, and also about the policy of non-treatment: the lack of any attempt to prevent or stop the pneumonia. Two claims were made about the drug. It was used only to relieve pain, not to accelerate death. And the nurses’ discretion over its use was such that Dr Arthur’s prescribing it could not legally amount to an attempt. It was argued that the policy of non-treatment was not an attempt to bring on death, but a holding operation intended to be reversed if the mother changed her mind. It was said that the policy involved no positive act of killing, but the creation of circumstances whereby the child would peacefully die.

It is clear that the verdict does not legitimise the use of a drug to speed up death, since the defence claimed that this was not the policy. Does the verdict support the view that a policy of non-treatment, of allowing a severely handicapped baby to die, can be legal? Even this is not clear, since the verdict of not guilty could have been based on accepting the claim that a reversible holding operation is not an attempt, without taking a view on the wider issue of whether deliberately allowing a patient to die is murder. So doctors may be unwise to accept Mrs Scarisbrick’s account of the position.

But the case is not just a legal matter. It raises issues of public policy and morals. In the debate in leader columns and in letters to the newspapers, these have almost all been oversimplified. Three issues need public discussion. There is the legislative issue: what should the law allow or provide? There are questions of decision and responsibility: assuming the law leaves some scope for decision in these cases, who should take the decisions? And there is the underlying moral issue: what is the right course of action? Or rather, since no single answer may fit the variety of cases, what principles should guide the decisions?

In the debate, opposed informal parties have formed: the ‘pro-life’ party and what can be called the ‘medical defence’ party. Their disagreement has been characterised by misunderstanding, partly caused by not keeping the three issues separate, and so not noticing that the parties each think a different issue is central. The medical defence party gives priority to questions of decision and responsibility. They argue that the decisions should be taken by doctors in consultation with parents, and support leaving the moral questions largely to their judgment. The pro-life party gives the moral questions priority. And their firm position on these makes them confident that there is little which can justifiably be left open for anyone to decide. They also favour the decisions they think wrong being legally prohibited.

One view has not been heard. This is that the pro-life party are right, as against the medical defence party, in thinking the moral questions have a kind of priority, but that they give misguided answers to those questions. Yet this view suggests itself when the rival orthodoxies are examined.

Consider the view of the medical defence party: that the issue of who takes the decisions has priority. It is a characteristic of our society that, finding deep moral disagreements intractable, we try where possible to convert moral issues into institutional ones, though it is to the credit of doctors that they do this to claim that the decision should rest mainly with them: the more usual function of this move is to shuffle a difficult decision onto someone else. Few public statements welcoming the verdict discussed the issue of the rightness of the policy of non-treatment. The statements stressed the autonomy of doctors in reaching and acting on their professional judgment, and the undesirability of interference with this by spies in hospitals, or by outside pressure groups, or by the law in general. In his own statement after the trial, Dr Arthur said: ‘The essence of the relationship between a patient and a doctor, parents and doctor, is trust and privacy. Perhaps the worst aspect of this case has been the breaking of this. My prayer is that trust and privacy can always be safeguarded in future.’ This echoed the condemnation of interference by pressure groups (bracketing together both LIFE and EXIT) which was made, when he gave evidence, by Sir Douglas Black, President of the Royal College of Physicians. And even criticism of doctors’ decisions was deplored, in a discussion reprinted in World Medicine, by the Secretary of the BMA, Dr John Havard:

The ordinary member of the British public has confidence in his doctor and believes he will take the right decision. The fact is that we have a medical ethic which develops as these awful things occur and we are subjected to criticism by lawyers, theologians, politicians, moralists and organisations such as LIFE. But we intend to continue to employ our ethical principles in the best interests of the patients we serve and who have great confidence in us. What we might end up with is a panel of lawyers, theologians, sociologists and God knows who, when it’s the doctor that is going to have to take the decision at the time without certain knowledge of what is going to happen. It really is quite monstrous that we should be subjected to all these criticisms.

The case for minimising the intervention of the law in these matters is a powerful one. The law here is a blunt instrument. Parliamentarians drawing it up, and courts interpreting it, are most unlikely to be able to produce anything sufficiently finely tuned to the complex circumstances of the particular case. Doctors, unlike MPs and lawyers, make their judgments with knowledge both of the current state of medical technology and of what the evidence suggests is likely to be the kind of life open to a baby with a particular handicap. Keeping the law out allows scope for the characteristic virtues of ‘situation ethics’: flexibility, a compassionate response to the human problem and to the particular people involved. And some may share my view that these qualities are particularly highly developed among doctors, whose intuitive judgment of the issues often seems so much more sensitive than that of MPs, lawyers or philosophers.

But, despite the strength of this case, we should recognise that it presupposes a view about the moral questions. The decision cannot be just a medical one. The judgments doctors are good at, about prognosis and about the psychological capacities of the parents, are of course highly important. But there is also the moral question of whether, given all this, it can be right to decide for the death of the baby. People who believe in the sanctity of life in its stronger forms will not accept that any facts about prognosis or family circumstances could justify allowing a viable baby to die, let alone justify any positive steps to accelerate a death. And this kind of view is not held only by pressure groups or religious bigots with no knowledge of medicine. These moral issues not only divide our society as a whole, but also surface within the medical profession. Doctors disagree with each other in ways that do not simply reflect technical differences.

The case against pressure groups having informers in hospitals is again a strong one. Dr Arthur rightly stresses the importance of medical confidentiality. And medical teams, especially when working together under the pressures generated by these sorts of cases, need an atmosphere of mutual trust. It must be hard enough to reach good decisions without the anxiety and suspicion that spies and informers would create. But again the issue is complex. There are real problems for nurses who disagree with the policy of non-treatment. Because the medical profession is so hierarchical, they may have difficulty in obtaining a hearing. And, even if they are heard, the decision may go against them. If, taking a sanctity of life view, they see the policy of non-treatment as one of murder, what should they do? In other contexts, we do not think people should co-operate in murder because they are ordered to do so, or to preserve confidentiality, or to keep up the morale of those they work with. It may be said that they should refuse to participate themselves but still not act as informers. But again, given their belief that a murder is being committed, it is not obvious how this passivity could be justified. Is there no duty to sound the alarm when someone is being murdered? In other contexts, we admire ‘whistle-blowing’, where people put the public interest before loyalty to colleagues. It is hard to understand the doctor who holds that abortion is murder, and so will not perform abortions himself, but instead will refer women to other doctors who take a different view. Can he really think it murder and yet be so co-operative? Similarly, the demand for silence from the dissenting nurse seems not to credit her with really holding that non-treatment is murder.

The medical defence party has good reasons for wanting these decisions to be free from legal interference and for opposing the growth of informing. But the argument in each of these cases succeeds only on the assumption that the sanctity of life view is not accepted. The underlying supposition is that we do not have to give the preservation of life overriding priority over all other considerations. And this view, while defensible, is controversial. In this way, the pro-life party are correct when they give priority to the moral questions. For on our answers to them depend our answers to all the other problems.

Consider now the views of the pro-life party. They rightly do not try to evade the moral issues. Other faults characteristic of our society are displayed in their approach. They assume that the answers to moral questions are obvious. And they assume that they are simple.

The view is that the pro-life position, whether on severely handicapped babies or on abortion, is so obviously the right one that no sane and decent person could disagree with it. This view is itself fairly obviously false. (Dr Arthur is himself an obvious counter-example, and we all know sane and decent people on both sides of the abortion debate). Yet this view surfaces all the time in expressions of the pro-life stance.

Consider the picture of those who disagree which is presented in a recent attack on contraception and abortion by Professor G.E. M. Anscombe*:

One could say: if you want to promote abortion, promote contraception. We now live in a kind of madness on these themes, in which vocal people at large are completely thoughtless about the awful consequences of far less than reproducing the parental generation, where it has itself been a large one. Our schools are already suffering, as professional teachers know, and what they can offer in the way of specialist teaching, such as the teaching of music, for example, is being cut down. Nor is it difficult to smell prospective murder in the air: so far, we have the murder of defective infants, but among young doctors we hear mutterings about the senile occupancy of valuable beds. These are likely to be echoes of what is said by older members of the profession.

It seems harsh to dismiss as ‘completely thoughtless’ those who suspect that cuts in music teaching may have more to do with monetarism than with contraception. And it is also a harsh dismissal of those who think that while more children may mean more music classes, this is not a decisive case for abandoning contraceptives. The confidence on this matter is perhaps a spill-over from confidence that doctors acting on a different moral outlook are best thought of as murderers, and that other dissenters exhibit ‘a kind of madness’. This is not a merely eccentric passage. In many statements of the pro-life view, the belief in its obvious rightness generates this combination of the denunciatory tone with a style of argument which can charitably be described as relaxed.

The supposed obviousness of the pro-life position perhaps results from its simplicity. The central claim is that babies and foetuses (other than those with fatal abnormalities) should never either be killed or denied routine positive treatment necessary for saving their lives. The inclusion of foetuses here is not a marginal point, but one stressed by LIFE itself in its publications: ‘More people are shocked by neo-natal than by pre-natal killing. If they reject the former, we can go on to ask: “Why is it any less wrong to kill a few weeks earlier?” In other words, we can use these cases to help people to perceive the enormity of abortionism.’† This standpoint gives overriding priority to being alive, regardless of the degree of handicap or the kind of life it allows, and regardless of the views of the parents or the effects on the family. When questions are asked, the feeling that the view is simple and obvious may be replaced by the feeling that it is only simple. When we ask why keeping the child alive is always to override sparing the child or the family a lot of misery, three different answers, not always distinguished, are often given. One is a slippery slope argument about the dangers of eroding respect for life. Another is the claim that there is an absolute moral prohibition on taking innocent life. A third is that the child has an inviolate right to life.

The slippery slope argument obviously has something to it. We all remember what grew out of the Nazi euthanasia programme. This thought is enough to remind those of us who disagree with LIFE about severely handicapped babies that society should set limits on what decisions resulting in death should be tolerated. But the slippery slope argument does not seem decisive support for the pro-life view. To justify the misery that view causes, it has to be shown to be plausible that we will slip down the slope. And those of us who do not recognise the doctors we meet in the ones whose muttering Professor Anscombe overhears will want more reasons in support of this than have so far been supplied.

The weight of the pro-life case rests on the more immediate considerations, about the absolute prohibition on killing, or about the inviolable right to life. The appeal of these principles comes in part from their close resemblance to a view accepted by all parties to the debate. There are very strong objections to killing people, and to avoidably letting people die. In the overwhelming majority of cases, these objections should override other considerations. But this view, which we all accept, cannot justify the pro-life policy. To avoid the humanitarian exceptions, the prohibition has to be absolute and the right inviolable.

But where does the inviolability come from? If from a particular religion, the rest of us need not be murderous or mad to dissent. If not from religion, some other argument for it would be welcome. The need is clear in the abortion debate, where the right to life is opposed to the woman’s right to choose. Where do these rights come from, and on what basis does one take priority? And if the right to life is more than a right not to be killed, but also a right to treatment, what implications does this have in a society where many people die each year because of lack of medical funds? Since the Arthur case, the newspapers have carried reports of 97 children who would have died for lack of bone marrow transplants but for the intervention of a generous millionaire, of a thousand or so people over 45 dying last year because of a scarcity of kidney transplant facilities, and of government cuts closing a London University medical department developing a technique to save the lives of children deficient in vitamin B12. LIFE has made no statement about these matters. Is this for the reason – a very good one – that no one can campaign about everything? Or does the principle of the right to life not extend to these cases? If not, some explanation seems called for. And if the right to life does bear on these other cases, there are large questions about how far we should go in giving life-saving priority over other aims. Until these questions about the basis and scope of the inviolable right to life have been discussed, it is naive to imply that any simple view is obvious.

Another part of the pro-life case is a criticism of the grounds cited for the humanitarian exceptions. When doctors and parents come to the view that a baby’s life is likely to be so awful that death would be a mercy, this is objected to. Mrs Scarisbrick was quoted as saying:

It is when they start talking about quality of life that alarm bells ring because they are not being doctors any more but judges. Nobody can judge another person’s quality of life, or decide for them whether it will be worth living. I cannot predict that. You cannot. I do not see that a doctor can, with or without the knowledge and consent of the parents. Nobody has the right to kill another human being.

There is surely something right about this. The decision that someone’s life will be too terrible for it to be humane to keep them alive is extraordinarily hard, and only too obviously a fallible one. But does it follow that it should never be taken? Those deciding not to prolong the life of someone whose prospects look so poor must live with the knowledge that their choice may have been wrong. But those who decide the other way have to live with that knowledge too. Is it obvious that our fallibility should come on one side of the-scale only?

What should be the position of those of us who are sceptical of the pro-life view? In the long term, the problem Dr Arthur faced should become less common, because of antenatal screening. (This is no comfort to the pro-life party, given their views on abortion.) But parents and doctors have to take decisions now. It is hard on doctors to have these decisions distorted by anxieties about possible prosecution. Two plausible factual claims can be made. Legislation to give more discretion to parents and doctors (quite apart from its drawbacks) is unlikely to be achieved in the present social climate. But equally, juries are highly unlikely to convict doctors acting in good faith in these cases. It would be reasonable for the authorities in charge of prosecutions to recognise this, and to indicate that such prosecutions of doctors are not in the public interest. They could indicate that they will not bring prosecutions where parents and doctors agree to allow severely handicapped newborn babies to die. They are also able to take over a private prosecution and ensure its failure by bringing no evidence. Those of us who think these decisions are best taken by parents and doctors, and best taken not under legal threats, should press for something of this kind.

Some final thoughts on the public debate. Its deficiencies reflect much wider disagreements about morality. In our society a morality derived from religious commands and prohibitions is declining, but still powerful. And there is no commandingly popular alternative among the possible successor moralities. Consequentialist views, such as utilitarianism, vie with rights theories, and also with agent-centred views stressing purity of motive and character. Many people have an eclectic mixture of these, with no general agreement on the criteria to be used in moral debate. So it is unsurprising that sustained discussion of ethics is rare. Not knowing how to think about moral decisions, we think instead about who should take them. Or discussion gives way to denunciation and simplification.

There is no certainty, perhaps even no likelihood, that our divisions on these questions will ever quite disappear. On both sides of the debate are values with a deep hold on us. But the defensive-aggressive tone of the discussion could give way to something different. If the pro-life people would like the rest of us to listen, they could try talking instead of shouting. It would have been nice to hear people from LIFE saying the favourable things about the motives and character of Dr Arthur that everyone else said. It would have been good to hear that they realised what the prosecution must have meant for him and for the baby’s parents, and to hear that they had looked for other ways of making their point. Is it impossible to concede that some cases of survival may turn out a nightmare for the survivors and for their families? And does Mrs Scarisbrick have to refer to those who disagree as the ‘death lobby’?

What about those of us on the other side? Some changes of tone suggest themselves. It would be good not to hear ‘Catholic’ used as a dismissal. The case against the pro-life view does not depend on contempt for religious views. And we should be more open about the fact that our concern is not just for the severely handicapped baby facing a terrible life, but often for the family as a whole. It is implausible to say that life for a baby with Down’s syndrome has to be awful, but we may still sometimes think it right to let one die rather than wreck the lives of the rest of the family. (Of course there are cases where such babies have enriched the lives of their families. Everything here depends on the individual circumstances.) We should also admit that it is much harder to justify allowing someone to die in the interests of his family than in his own interests. There are large issues here, which are not adequately discussed because of a propagandist desire to slur them over.

We need not be so defensive. Like the pro-life view, the opposing view has unresolved problems, on which progress will only be made as we be become more open about them. Finally, we can recognise that the prosecution was initiated by decent people, for reasons we can respect, and be glad they were denied the success which would have cost others so much.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.