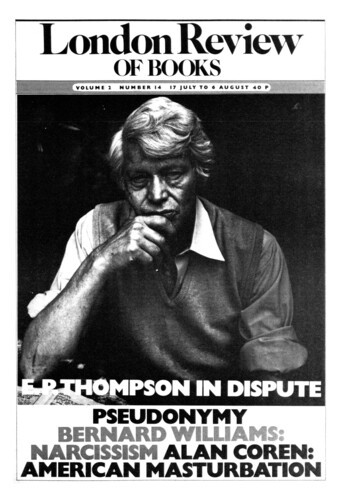

English Marxists in dispute

Roy Porter, 17 July 1980

The Englishness of English historians lies in their eclecticism. Few would admit to being unswerving Marxists, Freudians, Structuralists, Cliometricians, Namierites, or even Whigs. Most believe that blooms come best in mixed bunches. They may allow themselves some guarded asides on the psychology of chiliasm, but would reject Norman Cohn’s full-frontal psychopathology of antisemitism. They probably accept, as true for that decade, Sir Lewis Namier’s vision of the politics of the 1760s as dominated by clique and pique rather than by constitutional principle, but would hesitate about his overarching behavioural conservatism. Call this open-mindedness, pussy-footing or Vicar of Bravery, it has been saluted as part of the historian’s craft by many different figures from Karl Popper to Arthur Marwick.