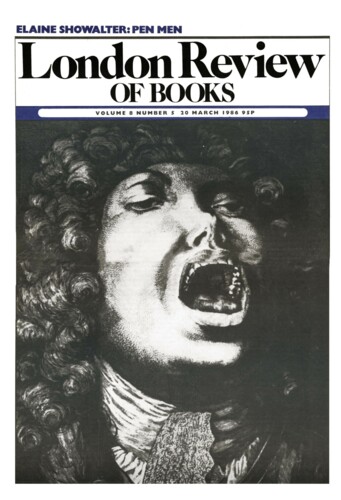

Prinney, Boney, Boot

Roy Porter, 20 March 1986

Cherished among the bastions of our ‘invisible constitution’ is the political cartoon, the people’s daily retort to ministerial humbug and opposition hypocrisy. If the pen is mightier than the sword, the sharpest pen is surely the cartoonist’s: one palpable hit from him will do more than months of routine pounding from lumbering leader-writers. This may be common knowledge. But is it true? After all, media experts of every hue – and not just those who see the press as the poodle of the powerful – have long been questioning the radical potential of mass culture. Many enjoin scepticism towards all assumptions about the ‘influence’ of print (and, by extension, ‘prints’) upon people’s minds. Others stress how the mass reproduction of images produces apathy, the anaesthesia of familiarity. Institutionalise criticism, and you draw its sting.’