Phillip Knightley

Phillip Knightley’s most recent book is The Second Oldest Profession, a history of intelligence agencies.

Disinformation

Phillip Knightley, 8 July 1993

After the break-up of the Soviet Union, the KGB began to make approaches to the Western media, offering its collaboration on various spy stories. The most ambitious was a television documentary series on the history of the KGB. The bait was tempting: within its archives the KGB claimed to have film of some of its operations dating back to the Twenties and, for later periods, voluminous video recordings that included surveillance of suspects, interrogations and confessions. Thirteen one-hour programmes on the lines of the famous World at War series did not seem too ambitious. In 1990 I had a telephone call from a London producer who said he was about to fly to Moscow to sign with the KGB. Would I consider being a consultant? I urged caution but he assured me that in his contract he would insist on complete editorial control. He announced his deal in the Western press a few weeks later. Soon afterwards, an Italian documentary company revealed that it, too, had signed to make a TV series based on the KGB files. This was followed by a Japanese company and then, finally, Hollywood. All believed that they had exclusive rights.

Cowboy Coups

Phillip Knightley, 10 October 1991

In the summer of 1975 I was invited by a man I knew had contacts in MI5 to have lunch at the Special Forces Club in Knightsbridge. He wanted me to meet ‘someone from the office’ who had a story which might interest the Sunday Times, where I was then working. There was another guest, an aristocratic young man from the City whose role appeared to be that of prompting the MI5 officer – for that is what I took the man from ‘the office’ to be – when he hesitated over a real or pretended indiscretion. The conversation was all to do with the extent to which the Russian Intelligence Service had penetrated British life. The MI5 officer quickly dispensed with the Wilson Government – its penetration was taken as read – slandered Wilson’s own loyalties and those of several members of his Cabinet, and then moved on to the Royal family.’

When Kissinger spied for Russia

Phillip Knightley, 11 July 1991

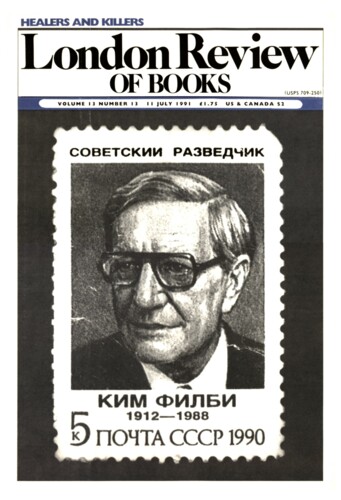

In the international intelligence community, (a loose term to cover spies, spy writers and spy groupies) there are two views on Kim Philby. One is that after he fled to Moscow he was a burnt-out case, a pathetic drunk living on the memory of his great triumph – fooling the West for thirty years. In this scenario, Philby drank to drown the thought of what might have been. If only he had not been so friendly with Guy Burgess, whose follies gave Philby away, he might have become director-general of the British Secret Intelligence Service, Sir Harold Philby, invulnerable to exposure and in a position to have handed the British and American services to Moscow on a plate.

Reverse Discrimination

Phillip Knightley, 19 May 1988

At the beginning of this puzzling book the author, Bernard Wasserstein, Professor of History and Chairman of the History Department at Brandeis University, offers his excuses for writing it. It is, he says, the story of a man who left barely any footprints in political history and whose literary relics are without enduring value. As a further turn-off Professor Wasserstein confesses that his colleagues are unlikely to regard the life of Trebitsch Lincoln as a significant contribution to the advancement of historical understanding. In the afterword Wasserstein returns to this point. He says Lincoln left nothing of enduring value: and yet his story ‘seems somehow to mirror, albeit in a grotesque and distorted fashion, the unquiet spirit of the age.’

Pieces about Phillip Knightley in the LRB

Lucky Kim

Christopher Hitchens, 23 February 1995

While I was still reading these books, and thinking about them, I chanced to have two annoying near-KGB experiences. A creepy individual named Yuri Shvets published a book called Washington...

Great Internationalists

Rupert Cornwell, 2 February 1989

Only at the very last did my path cross that of the Cambridge spies. It was on a warm, sunny afternoon last May at Kuntsevo Cemetery on the western outskirts of Moscow, when they buried Kim...

Poor Stephen

James Fox, 23 July 1987

In a recent letter to the Times, Lords Hailsham, Drogheda, Carrington, Goodman and Weinstock, and Messrs Roy Jenkins and James Prior, said they felt it was a good time, in view of the new...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.