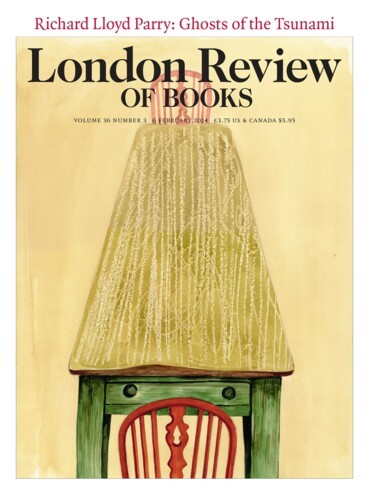

‘Madness is a childish thing,’ Barbara Taylor writes in The Last Asylum, a memoir of her two decades as a mental patient. The book records her breakdown, her 21-year-long analysis, her periods as an inmate at Friern Mental Hospital in North London, and in addition provides a condensed history of the treatment of mental illness and the institutions associated with it. Taylor was in the bin during the final days of the old Victorian asylums, before they were shut down in the 1990s, and their patients scattered to the cold liberty of the underfunded, overlooked region of rented accommodation.

I return to the complete mystery of why some people are knocked flat and incapable by what seem like only the mildest of dysfunctional backgrounds, compared to others whose childhoods were devastated by cruelty and deprivation, let alone those who grow up with famine and war, yet seem to find a way to live their lives as if they were their own. And all that space in between the extremes of near harmlessness and full-blown misery: the whole regular family muddle and mess that everyone has to survive, or not.