Alan Macfarlane writes about the crisis in Nepal

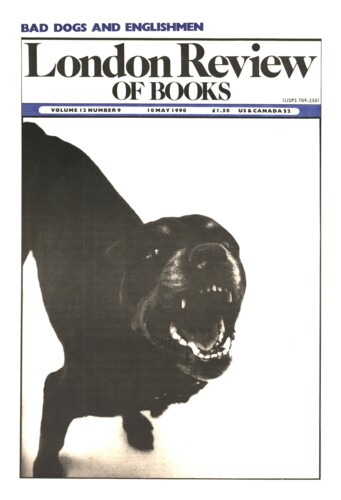

Alan Macfarlane, 10 May 1990

The current political revolution in Nepal marks a further stage in the rapid integration of that country into the Western capitalist world. From a standing start in 1950, when the Ranas were overthrown and Nepal began to be transformed from a medieval oriental despotism into a modern nation-state, a great deal has been done. Between 1950 and 1980 the cumulative growth in various sectors has been estimated as follows: ‘70 times in power generation, 13 times in irrigation facility, 134 times in school enrolment, 12 times in number of hospital beds’. A literacy rate of 2 per cent in 1951 had been increased to over 40 per cent in the late Eighties. There are now more than a hundred and fifty university campuses. Epidemic disease has been almost eliminated. Infant mortality rates have been halved. Piped water has been brought to most villages. An international airline has been started. Nepal now exports goods worth more than twenty-five million dollars a year. A large tourist industry has been created, with over 300,000 tourists (other than Indians) a year. Kathmandu and other towns have grown remarkably and now have many facilities, including television, computers and many modern goods and services.