Saafir 1970-2024

Alex Abramovich

An interview with Saafir showed up on my Instagram feed last November. Jason Moran posted it with the caption: ‘There have been many MCs that I’ve felt artistic symmetry with, but maybe none as aligned as this man.’ When I spoke with Moran more recently, he recalled listening to Saafir as a student. ‘I could transcribe this,’ he thought. ‘As a pianist, I was sitting there, writing it down. This was something I could learn from.’

The knowledge passed both ways. ‘There’s talent in the Bay Area that motherfuckers don’t even know about,’ Saafir says in the interview. ‘Motherfuckers with skills like Eric Dolphy on flute and the sax. Motherfuckers like Andrew Hill, all cooking shit up. Hank Mobley – it’s motherfuckers that rhyme like that.’

Most MCs rap on beat. Saafir didn’t. He swung. ‘He didn’t rattle off Coltrane or Miles Davis,’ Moran pointed out. ‘He went: Andrew Hill, Eric Dolphy, Hank Mobley. He’s dealing with the outsiders.’

Born Reggie Gibson in 1970, he was raised in West Oakland, California, the East Bay’s historic blues district, where Lowell Fulson and Jimmie McCracklin held court. That world was swept away when urban renewal sliced through the neighbourhood with BART tracks, interstate highways and a massive mail distribution centre. In schools, music programmes vanished under the twin pressures of Proposition 13 – which froze California’s property taxes and gutted public education – and the fading of federal support for arts in schools. Musical kids had to find new ways to improvise.

Saafir got his start as a breakdancer. On his own since the age of twelve, he cycled through group homes and juvenile detention centres. By his own account, he spent all but ten months of his teens in the system, and was behind bars when he heard LL Cool J for the first time and thought: ‘I can do that.’

He formed a hip-hop crew with Plan Bee. ‘We used to fool with jazz real deep,’ Saafir said in an interview in 2006. ‘I came across a Jimmy Smith record called “Hobo Flats”. And the way we was living at the time, we was like hobos. We looked fresh. We stayed crispy. But we was living hard.’ Plan Bee suggested the name ‘Hobo Junction’.‘The way it rang,’ Saafir said, ‘just felt right.’ When Plan Bee was killed, shot multiple times in a murder that never was never solved, Saafir kept the crew going.

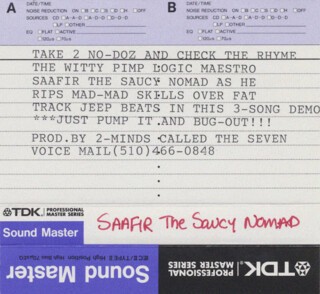

There’s a stretch of mid-1960s Blue Note LPs – albums like Blue Spirits, Grass Roots, Mode for Joe – where the players are feeling their way towards free jazz but don’t stray too far from the pocket. These are the records I think of when I hear Saafir. ‘Playa Hater’ is built around a short, dissonant vibraphone sample lifted from Eric Dolphy’s ‘Hat and Beard’ (itself a tribute to Thelonious Monk). Dolphy’s tune opens in 9/4 but the rhythm section doesn’t behave, with Bobby Hutcherson phrasing in off-centre bursts. Saafir was well on his way to rapping like that on his very first mixtapes.

He was newly out of jail, couch surfing, carrying his clothes in a bag, when he stood up for a woman who’d been hit at a party. The next day, Tupac Shakur called:

‘I heard you beat the crap out of this fool. Why’d you do it?’

‘Because he slapped Money B’s cousin.’

‘Yeah, I know – but why’d you do it?’

‘Because he slapped Money B’s cousin.’

Money B was Shock G’s partner in Digital Underground. Shakur was Shock G’s protégé. Saafir moved in with him and joined Digital Underground as a dancer and as-needed muscle.

He didn’t stop rapping. He made an appearance on the first album by Casual, of Oakland’s Hieroglyphics collective. When Casual flaked on returning the favour, the rap battle that ensued reshaped hip-hop’s geography. It put the Bay on the map, but there were rumours that Saafir had come to the battle with ‘writtens’. He had. For Saafir, writtens weren’t a crutch or a fallback; rhythmically, they gave him more room to move. (In another battle, he managed to pick Casual’s pocket, mid-verse.) ‘I focused on the placement,’ he said. ‘’Cause wasn’t nobody hitting the pockets the way I was hitting it.’

Saafir had a part in the Hughes brothers’ movie Menace II Society. He had a verse or two on Digital Underground’s next album and recorded the Boxcar Sessions for Quincy Jones’s label, Qwest: ‘It’s best you let me wander/Or I’ll/Taunt you …’ The beat was East Coast boom-bap. The delivery pointed, askew. The words, less a warning than statement of fact. ‘Motherfuckers clowning me, trying to diss me,’ Saafir said. ‘Some say I don’t rhyme on beat, but actually I do. It’s just the way that I swing it, it’s hard for you to catch it.’

The phrasing reminds Moran, who studied with Andrew Hill, of his old teacher:

Saafir was eluding the pocket, almost elevating above the beat and then dropping back in, then diving underneath the beat and coming back to where it is on the surface. But he’s never staying with the beat the whole time.

Andrew had a stutter in his speech, and I felt like the way he was playing was just the way he heard phrases. He once told me: a bar is like a bubble – you can slice it however you want. It does not have to align equally. We’re not in a chef’s kitchen, chopping onions to exact size.

‘I would listen to a lot of jazz,’ Saafir said. ‘How John Coltrane would hit it in those pauses. I was like, wow, if I spit a rhyme like that, that would be cold.’

His style evolved, evened out. ‘I don’t particularly rap like I did in the 90s,’ he said in his forties. ‘I’m more focused on substance and content, as opposed to how I swing a rhyme. But I’m always going to swing a rhyme with flavour.’ A supergroup with Xzibit and Ras Kass didn’t produce an album. A brief signing to Dr Dre’s Aftermath label yielded nothing.

In July 1992, Saafir boarded TWA flight 843 from New York to San Francisco. It aborted on take-off and caught fire. Saafir was the first one out, having helped a flight attendant force the door open. He landed on a slide that had not inflated fully, injuring his back, and over the years the bad luck compounded. In 2005, a tumour was discovered in his spine. Surgery was successful until a numbness began in his feet and crept upward.

Shock G described Saafir grinding his meds up: ‘He continues to ride-out the pain (“Blood, I’ma soldier”) while flippin his pain meds for cash.’ By 2013, Saafir was paralysed from the waist down. He gave his car away. Without it, he couldn’t get to physical therapy. Eventually, he couldn’t get out of bed. ‘Getting into the bathtub – that’s like a marathon for me,’ he said. ‘Alone, it’s damn near impossible.’

Garrett Caples, a poet who knew Saafir, recalled him ‘living on somebody’s couch and just kind of being tolerated’. ‘He was a deep guy but very scarred, very touchy,’ Caples told me. ‘The idea of having to be dependent on other people physically was horrifying for him. It’s just not how he lived in the world.’ ‘I’m a boss,’ Saafir told Caples in 2013. ‘But I’m an injured player in the game. I’m a very strong injured player in the game, and I can still make plays from my position.’

I saw Moran at SFJAZZ a few weeks later. His set began with a few skaters on a small ramp, skating to Moran’s interpretation of the Oakland classic ‘93 ’til Infinity’. Moran had also thought about staging the Boxcar Sessions, in full, with Saafir onstage. ‘How many times it came into my mind,’ he told me. ‘I never acted on it.’ At the Manhattan School of Music, he said, he’d carved Saafir’s lyrics into his classroom desk. At the end of the semester he removed the lid and took it home. Saafir died on 19 November 2024. Moran still has the desktop.