On Felix Shumba

Marissa Moorman

The female cabbage tree emperor moth (Bunaea alcinoe) is the size of a human hand. I saw one in 1992 in Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands, where the Vumba mountain range runs along the border with Mozambique; in the 1970s, ZANU guerrillas fighting for independence from white Rhodesia had hidden in the area. I snapped a shaky photo of the giant moth, beneath a dull outdoor light, with a pocket camera. I don’t know whether I still have the print, but it doesn’t matter. The image stayed with me. The moth was alone. Still. Unbothered. She seemed to own the night.

I remembered the moth when I visited the artist Felix Shumba at the International Studio and Curatorial Programme in Williamsburg, Brooklyn in March this year. Shumba, an artist from Zimbabwe, spent three months in the converted industrial space of the ISCP. Charcoal drawings hung on the walls. File folders were arranged on the floor in neat rows. Shumba had drawn oversized bugs on them in charcoal, including a moth.

He makes the charcoal himself. It is light in the hand but his images are full of gravity. The human and animal figures sometimes seem to lift from the paper, as if they could step into the room.

Shumba lives and works in Masvingo, south of the Eastern Highlands. The monumental dry stone constructions of Great Zimbabwe, dating from the 11th century, are nearby. In the remains of the ancient city, archaeologists have found evidence of Chinese celadon and porcelain, imported glass beads, Islamic pottery, and tools and weapons in bronze and brass that show Great Zimbabwe was a node in a trade network that extended throughout southern Africa and across the Indian Ocean. The population made pottery, wove cloth, farmed, hunted and mined.

When European explorers saw the structures in the 19th century, they couldn’t accept that they had been built by local people, but instead came up with implausible theories for who was responsible, not excluding the Queen of Sheba. Other European visitors were less concerned with provenance than with looting the site. Cecil John Rhodes focused on what it indicated about the area’s mineral wealth.

The two largest mines currently operating, Renco and Bikita, both opened in the colonial period. Renco is now owned by RioZim, formerly part of Rio Tinto; Bikita is owned by the Chinese conglomerate Sinomine. At Renco they still mine for gold, but Bikita is now one of the biggest lithium operations in Africa. The mines operate 24/7. Constant day confuses all life forms. Shumba described finding piles of insects beneath the tall lamp posts: some dead, some half-eaten, some struggling to escape.

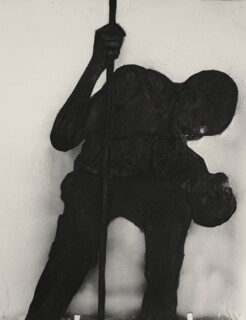

Among the works I saw at his studio in New York were a triptych, entitled and in the glass, like moonshine – the hue was purple/saturn devouring his son, and a diptych entitled Dog Eat Dog. They are dark, for sure. But their darkness invites thought, and Shumba himself thinks deeply and expansively. One wall held fifteen nearly finished pieces, a gallery of faces. Shumba’s portraits address you directly with the ambivalence, fragility, darkness and monstrosity of humanity. Eyes are white discs. Teeth are sometimes sharpened. Heads are cocked, in wonder, horror or perplexity. One wears a First World War helmet; and two figures, drawn in two-thirds profile, look like 19th-century cut paper silhouettes of European men. Shumba described the figures as onlookers, the crowd at the Colosseum, not just witnessing a fight but transformed by the collective act of egging on the violence. Viewers wounded by spectatorship.

Shumba had salvaged the manila file folders on the floor from garbage bins on a walk in the neighbourhood. The files contained photographs and news clippings. Each was titled: ‘Oil Spill’, ‘WWII’, ‘Nazis’, ‘Gummi Bears’. Shumba drew the insects on top: a moth, a beetle, a spider, a centipede. I supposed the trove had been dumped by a newswire service or a journalist, now fully converted to digital archiving or simply defunct. The files – headed for landfill, a discarded record of 20th-century crimes against humanity and the environment – were not merely a new surface for Shumba. They helped him draw a line from Williamsburg to Masvingo.

Mining companies cut down trees to make timber supports for the underground tunnels. Local women take what’s left to sell as firewood, and Shumba gathers it to make the charcoal he draws with. In his practice, collecting is cataloguing. He records the GPS co-ordinates of the wood he forages, before heating it for five hours in an oxygen-free earthen oven. Different trees produce different charcoals: a more bold or more elegant line, a denser or lighter layer.

One of the trees often cut to build mine supports, which Shumba uses to make much of his charcoal, is known in Shona as mubvamaropa or mukwa. It grows across southern Africa, from Tanzania to Angola, and its other names include umvangazi (Zulu), morôtô (Sotho), mutondo (Venda), mokwa (Twana), onjilasonde (Umbundu), njillasonde (Kimbundu), mirahonde (Nhanyeka) and kiaat (Afrikaans). The Latin name is Pterocarpus angolensis, or winged fruit – the spiky seed pod is surrounded by a broad membrane – from Angola, a signal of where and when it entered the pages of European botany. The tree is prized for its wood and has anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial properties. Its sap is red. When the trunk is cut, the tree appears to bleed.

Shumba’s images are bloodless, though they tell stories of violence. The triptych he worked on at the ISCP takes inspiration from both Rubens and Goya’s paintings of Saturn Devouring His Son but extends the action. The cannibalistic power play is only one moment in Shumba’s unfolding story. In the first image, a man holds his infant son in one arm, the baby’s tiny hand flat on his father’s chest. The man’s eyes are focused on the child. In the second image, the father’s gaze has shifted: he looks like a deer caught in headlights, as the white discs of his eyes stare straight out from the paper and the child is exposed to the viewer, his small arm bent away from his torso by his father’s tight grip. In the third image, the father devours the son. The smudge and erasure along the image’s edges, at the mouth and nose, contrast with the way Shumba uses them to create variation in charcoal values in the first two images. Hung on an adjoining wall, the fifteen portraits are an audience to this spectacle, as are we.

In Dog Eat Dog, the dogs move between playing and fighting as the viewer’s gaze moves between the images in the diptych. Bared teeth can signal frolic or menace, in people as well as dogs.

Shumba’s work, like that of the American artists Kara Walker and Kerry James Marshall, evokes caricatures of Black men and women, the founding myths of racism, and the reframing and use of classical art history to tell us something about power relations in the present. Shumba also reaches into Zimbabwean history. The recursive gesture to mythology calls to mind the soapstone birds that sat on columns at Great Zimbabwe and the mhondoro (ancestral spirits) that transmit music to players of the mbira dzavadzimu. Mbira music is itself recursive. Artists play a certain repertoire, looping the past through the present, as melodies peel from the iron keys of the instrument. Shumba works within and around that tradition the way he works in and around the tradition of southern African artists.

He started working as an artist when he lived in South Africa in the early 2000s. Like many Zimbabweans, he had moved to a neighbouring country to escape economic crisis and political authoritarianism. In Johannesburg, a city built on mining, he worked on construction sites and in white-owned restaurants, where pictures by Black South African artists – Dumile Feni, Peter Cole – hung on the walls. He started drawing in notebooks. Over time, he began visiting artists’ studios and developing his own work.

I first met Shumba at the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica in early March 2025. He was with the Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda, whom he met at the Sharjah Biennale in 2023. Later that year, Shumba did a stint at Kia Henda’s studio under the auspices of Jahmek Contemporary Art in Luanda. A joint exhibition at Luanda’s Natural History Museum, Memories of a Poisoned River, followed. It included charcoal drawings of leafless trees, monochrome prints of multi-faceted gemstones, drawings of flora and fauna, and colour photographs, that ask viewers to grapple with the human and environmental costs of mineral extraction. A text by the New Orleans artist Imani Jacqueline Brown provides a narrative thread (‘the river remembers the arrival of extractivism’).

The female Bunaea alcinoe lives for only a few days as an adult moth. She emerges from her pupa at night and goes about the work of laying eggs, sometimes unfertilised. In the larval stage, their high contrast colouring – a black body with white spikes and red spots – warns predators away. As imagoes, the scales on their wings provide acoustic camouflage, protecting them from bats by absorbing the sonar. Moths are not attracted to artificial light – whether electric or flame – so much as thrown off by it. The moth I saw in Zimbabwe in 1992 came close to the light because she was disoriented. The species belongs to the Saturniidae moth family. It’s possible that the name comes from the markings on the moth’s wings, which resemble the rings of the planet Saturn. But she was not the moth on Shumba’s file folder or the Saturn from his triptych. This moth does not devour its children.

Felix Shumba’s work is showing at Tiwani Contemporary in London until 20 September, with Galleria Fonti at Panorama Pozzuoli from 10 to 14 September and at Artissima in Turin from 31 October to 2 November.

Comments